Claire Sicherman

"The preservation and transfer of memory is the most critical mission that children and grandchildren of survivors must undertake so as to ensure meaningful and authentic Holocaust remembrance in future generations."

Menachem Z. Rosensaft. God, Faith and Identity from the Ashes: Reflections of Children and Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors. 2015.

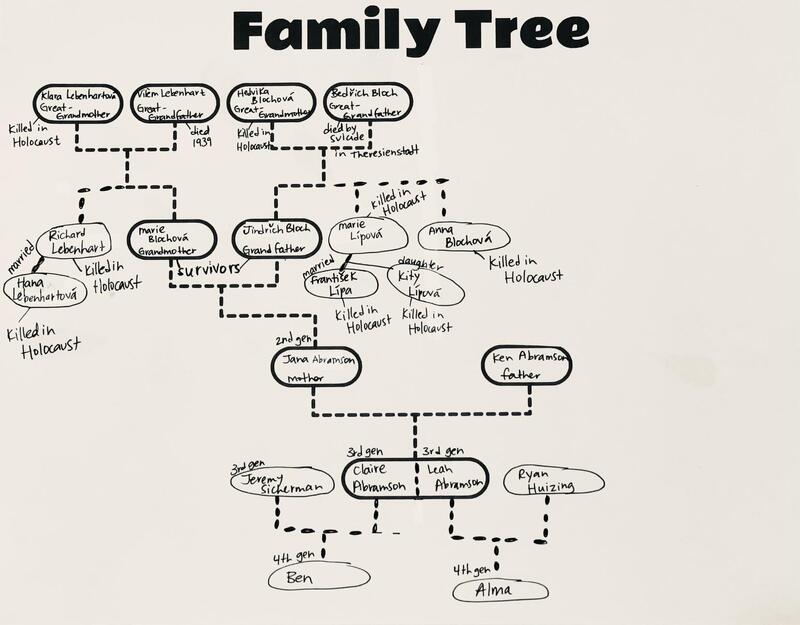

The importance of these words will become apparent as we explore Claire's narrative on her family that lost almost two generations in the Holocaust, leaving just her maternal Grandparents as survivors. The tragedy of Claire's family was repeated throughout Europe resulting in the deaths of six million Jews, and millions of other innocent people.

As a member of the third generation, Claire speaks and writes about the Holocaust and how trauma transmits across generations. Much of her work focuses on honouring and remembering her family through story and ritual. Claire’s son Ben is a member of the fourth generation, and she acknowledges the importance of including him and the next generations in the stories and rituals of honouring and remembering.

My Family

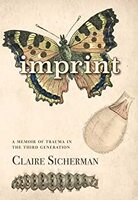

"My maternal grandparents were survivors of the Holocaust and I am their legacy. Every day I make a choice to keep creating new narratives for myself and to live my life in their honour, in the honour of all survivors, and in the honour of all those who perished in the Holocaust. There is an urgency to the stories of our survivors. My grandparents have passed away. Their voices were silenced, and when they were finally free to tell, they lost their ability to speak about the horrors, about the stories that were too hard to share. These remain buried. I may not have details of their trauma, but I carry their experience in my body, the violence transmitted through me, imprinted, and so it is from this third generation perspective that I write. Writing is one way of giving voice, of remembering, of processing, of grieving, of creating meaning and of healing. This is for you, my babi and děda. I love you."

Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation, p. 5.

Remembrance

Klára Lebenhartová Babi’s mother. My great-grandmother. Born March 1, 1883. Deported from Prague to Theresienstadt via Transport AAu, No. 808, and arrived in Theresienstadt on July 27, 1942. On August 4, 1942, Klára was deported via Transport AAz, No. 704 to Maly Trostenets in Belorussia. Klára was gassed. The exact date of her death is unknown. She was 59.

___________________________________

Richard (Rída) Lebenhart Babi’s brother. My great-uncle. Born October 27, 1914. Deported to Theresienstadt from Prague via Transport Di, No. 518, and arrived in Theresienstadt July 13, 1943. On September 6, 1943, Richard was deported to Auschwitz via Transport Dl, No. 1208. He was gassed on March 8, 1944. He was 29.

__________________________________

Hana Lebenhartová Babi’s sister-in-law, married to Richard. My great-aunt. Born June 23, 1920. Deported from Prague to Theresienstadt via Transport Di, No. 517, and arrived in Theresienstadt July 13, 1943. Deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz on Dl, No. 1207, September 6, 1943. She was gassed on March 8, 1944 at age 23.

__________________________________

Bedřich Bloch Děda’s father. My great-grandfather. Born September 9, 1871. Deported from Klatovy to Theresienstadt, September 26, 1942, Transport No. 257. On April 12, 1943, he committed suicide in Theresienstadt.

__________________________________

Hedvika Blochová Děda’s mother. My great-grandmother. Born February 28, 1879. Deported from Klatovy to Theresienstadt via Transport Cd, No. 258, November 26, 1942. Deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz on Transport Et, No. 1349, October 23, 1944. Date of death: March 1944. Murdered in Auschwitz. Cause of death unknown.

___________________________________

Marie Lípová Děda’s sister. My great-aunt, born Blochová. Born July 30, 1902. Deported from Prague to Theresienstadt on Transport Au, No. 420, May 12, 1942. Transport Ay, No. 481, May 17, 1942 from Theresienstadt to Lublin. Murdered. Cause and date of death unknown. No one survived from this transport.

___________________________________

František Lípa Děda’s brother-in-law, married to Marie. Born July 6, 1899. Deported from Prague to Theresienstadt via Transport Au, No. 418, May 12, 1942. Deported on Transport Ay, no. 479, May 17, 1942, from Theresienstadt to Lublin. Murdered. Date of death: August 13, 1942, in Majdanek.

____________________________________

Kity Lípová Děda’s niece. My cousin. Daughter of Marie and František. Born December 12, 1929. Deported from Prague to Theresienstadt via Transport Au, No. 419, May 12, 1942. Deported on Transport Ay, No. 480, May 17, 1942 from Theresienstadt to Lublin. Murdered at age 12. Date and cause of death unknown.

___________________________________

Anna Blochová Děda’s sister. My great-aunt. Born December 4, 1911. Deported from Klatovy to Theresienstadt via transport Cd, No.259, November 26, 1942. Deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz via Transport Eq. No. 204, Oct 12, 1944. Murdered. Date and cause of death unknown.

_______________________________________

More family members who perished in the Holocaust:

Rudolf, Eliška, Vilem, Karel, Rudolf, Marie, Anna, Julius, Max, Julian, and many more whose names we do not know.

Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation, p. 6-8.

_____________________________________

Excerpt from "Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the First Generation"

Journal Entry #100

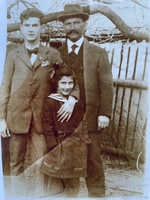

It’s Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day. The blossoms are so thick on the cherry trees that I can no longer see the branches. The spring sun is out and there are only a few wisps of clouds. In the Granville Island Market, I scan the buckets of flowers. I’m scouting for wild-looking ones: beach peas, delphinium, lilies, poppies, sweet clover, bleeding heart. I spot some anemones. They’re red. I choose them in memory of the blood that was spilled. I choose them to honour my family. Anemones grow wild. I picture them spreading over a grassy field that covers the mass graves of my ancestors. I pay $12.99 for a small bunch of these flowers. “Is this a gift or are they going home today?” the florist asks. I pause. “Um,” I seem to say forever. My eyes go fuzzy and I stare at the counter. Hard. “I think they’re for me,” I answer. “For home.” “Don’t put too much water in the vase, as they’re a soft-stemmed flower,” she says. “This will prevent them from rotting.” I want to tell her that I’ll be cutting them up. But I don’t. I thank her and I leave. Outside the market, seagulls with fat bellies waddle by the garbage container, looking for scraps. One finds a take-out container with leftover French fries and two others wander over. A fight breaks out and the biggest bird wins. I watch the seagull guzzle the fries whole, and fly off, crying out its song of victory. When I return home to our apartment, I Google and learn anemones are used for their medicinal properties in the treatment of menstrual problems and grief. I am a firm believer that our bodies know how to heal themselves. We simply need to learn how to tune in. I place the larger photos of my great grandparents along with my babi’s brother, Richard, on the wood table. Below, I place photos of my grandparents, and my great-aunt and her family. There’s even a family photo of my great-great-grandmother. Her name was Josefa. She sits outside on a white wicker chair. There is a cherry tree, plums, apples and pears. The grass is long and there are daisies. She is dressed in black. A large-collared, long-sleeved blouse and a skirt that flows down to her ankles. Her grey hair is pulled back away from her face. She holds her left hand in her right. She wears a ring on her right ring finger. She’s smiling and her four family members are standing behind her, smiling too. My Klára, my Vilém, my babi, and my Richard. I don’t understand how the photos survived, when most of my family didn’t. I am, however, grateful to have them. Next to the photos sits a typed list of names of our family members, and the anemones I cut at the top of the stalk. Beside the flowers, there is water sitting in a stainless steel bowl. I clear my throat. I am nervous even though it’s just the three of us. Ben and Jeremy look at me expectantly. I begin to speak about the Holocaust. I talk about how most members of our family were murdered, but I don’t mention details. I speak about how my babi and děda survived, and that we are here because of them. And I talk about how we must remember, how we must always remember. Then I turn to the photos. “Here’s your great-great-grandmother,” I say. Ben grabs an anemone. He is ready to start. I hold up the photo of my Klára, my namesake, and take a deep breath. “Dear Klára,” I say. My voice box begins to shake. “We love you and we will always remember you.” Ben watches me and I nod to him. He places the anemone in the bowl of water. The three of us watch the red drift in the silver bowl. We continue through the photos. We are learning how to grieve, practising how to mourn together. We are creating a ritual to make our own. I hold up the photo of my grandmother. “That’s Babi,” Ben says. I smile at him through my tears. “Dear Babi,” I say. “We love you and we will always remember you.” Ben puts another anemone into the bowl.

Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation, p. 199-201

______________________________________

Prague 2019

Ben Sicherman's Speech - August 14, 2019 (12 1/2 years old)

Hi, thank you all for being here with me on this glorious occasion. I just wanted to say I love you all and thank you for taking the ten-hour flight to be here, and for coming all this way to be here, in Prague, the city in which many of our ancestors lived.

First I wanted to talk about being a Fourth Generation and how it feels to be one.

I wanted to acknowledge all of your issues regarding intergenerational trauma and I realize how hard it may be for some of you to carry this stress and worry. As a fourth-generation, I feel a tiny bit of uneasiness or trauma from the Holocaust. I think the Holocaust was horrible and all the lives lost should be honoured. I’m also not saying just move on from it. All I'm saying is we can’t change what has already happened, and also instead of being weighed down by it, we can all consider our ancestors as a strength. By saying hey, I'm Jewish and there is nothing wrong with that.

One of the questions I asked was comparing the stress and trauma between the first to fourth generations.

This is what I feel is accurate:

First Generation: Babi & Dĕda: They felt it the most, likely because they survived the Holocaust.

Second Generation: Babu: Babu, you lived under the Communists, it was most likely a hard time for you. Also in your childhood, you had no idea you were Jewish. Probably because it wasn’t safe for you and your family to be Jewish so your parents hid their secret.

Third Generation: Jeremy, Claire and Leah. You carry around intergenerational trauma from the Holocaust and it shows in your personalities sometimes. It shows in how you act, you are more stressed than some adults I know as well.

Fourth Generation: Me myself and I. I do sometimes feel sad and a little frightened about what happened, and I also share some of the trauma. But I can honestly say I don’t share as much intergenerational trauma as you guys do. I feel some of the trauma in my heart, a place where I usually feel no worry at all. The generational trauma I carry in my heart feels like a stone in an Ocean. Just one stone in a huge amount of stones, it feels…empty and a bit sad.

And all of us are like stones in the ocean. Except we are all gathered here. A bunch of stones, and if you think about it, we are standing on stone. So we are a bunch of stones standing on one big stone (The Earth). It can be a bit scary sometimes. But we are together and that love helps.

Fourth Generation: Alma: Let’s watch her grow up and see what happens. Like me, I hope she won’t carry as much too.

Why is it important to be in Prague?

It’s ME Thirteenth Birthday ME dudes.

I’m half kidding. Why we are here is important for so many reasons. One of the reasons is that we are standing where our ancestors used to live. Another important reason is that I can learn what it was like for the thousands of people who were deported to Theresienstadt and then to Auschwitz-Birkenau and other death camps. Also, it’s important to me to experience Prague by using the five senses. I want to smell, feel, taste, see, and hear my ancestors. It’s important because they would appreciate it and it would make them happy to see us all together here.

Face The Facts.

Sometimes when my friends walk into school they brag about how many cousins they have. I often hear varied answers from between ten to one hundred and thirty. It just makes me stop because I only have four. Then I realize why; it’s the Holocaust. I estimate that if World War II never happened that we would have a way bigger family. It’s sad, but I feel like it’s true. A few days ago (July 8th, 2019) so I guess a long time ago now, I met my friend Grayson in town. We spoke for a while and one of the topics that came up was how many cousins we each had. I was tempted to lie about it and say around ten (because that’s what I thought most people had). I ended up telling the truth and saying four. Then Grayson surprised me by saying he had fifty-two cousins and I knew right then that it was the Holocaust that caused our family to be so small.

Now, I could’ve talked about anti-Semitism but I find it negative for this occasion. So I’m going to talk about what we can do about it. Anti-Semitism is a huge topic on the news. But, we have to acknowledge it is not just Jews in North American and European societies that are being treated poorly. For example People of Color, Muslims, and Migrants, well we have to admit it. Kind of everyone except white Christians, it’s sad but true. I don’t think we have to worry about another Holocaust, but I think we need to be careful who we tell that we are Jewish.

Another point about the Holocaust is that Jews were not the only ones to have suffered the same fate. People of color and even some Germans who were considered “not German enough,” along with millions of others were sent to the concentration camps. I read in a memoir that a prisoner who was pretty old was complaining that he shouldn't be in the camps because his dad served in the German army in WWI, but the Nazis laughed and shot him anyway.

In conclusion, I feel most grateful because our own Babi and Dĕda survived and that I am here because of them. If they were not here, then the glorious, beautiful and modest person that I am would not be here. (Don’t forget the modest part.) I love my ancestors very much and miss them with all my heart.

I want to use my voice to remember, to carry on the legacy of Babi, Dĕda and Klára and all those who either died or survived the Holocaust.

💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖💖

Thirteen. An essay by Claire Sicherman.

It’s the summer you turn thirteen when we travel to Prague to visit our ancestors. We have planned an alternative bar mitzvah, one that we hope will connect you with your roots.

I have read an article in The Guardian about the importance of doing this for kids, how children who have a strong family narrative are healthier emotionally. Is this still true if the family narrative includes genocide? I wonder.

Just to be clear, the ancestors I’m speaking about are not alive. Most were murdered in the Holocaust. My grandmother, a survivor, who passed away six years ago at the age of 102, wanted to die for as long as I could remember, while my grandfather, who also survived, took his own life when I was four.

We have been talking about the Holocaust with you for a few years now, since you were nine. You’ve read: The Diary of Anne Frank, The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Maus and Survival in Auschwitz. You are interested in weapons, in ways prisoners were tortured, in how people died. For a school project, you have written about the suicide of your great-great-grandfather in Theresienstadt, a transit concentration camp-ghetto outside of Prague, and the suicide of your great-grandfather in Vancouver. You ask bone chilling questions that I don’t have answers to, ones that make my stomach twist into knots.

When we first arrive in Prague, we head to Staré Město, Old Town, and cross over the famous Karlův most, Charles Bridge. The three of us hold hands as we snake through the hordes of tourists. We take a selfie with the Pražský hrad, the Prague Castle, in the background, the gothic towers of St. Vitus Cathedral, a beautiful golden sunset cradling our heads. You are smiling, the twilight exposing the glint of your metal braces, which were glued on your teeth earlier this year, your eyebrows bushy, your brown curls tightly coiled, your large grey t-shirt untucked, hangs just below your hips. In another photo, your dad wraps his arms around you, the sky now a shade of violet, the clouds a puffy dream. Although we just arrived, my body feels heavy, my arms like thick tree trunks, knuckles drag, back stoops, neck bent. While couples embrace, while college students drink pivo, Czech beer, while parents push strollers, their kids licking zmrzlina, ice cream dribbling down chins from August heat, I curve inward with the weight of inherited memory.

I squeeze your hand tight because I don’t want to lose you in the chaos. Squished through a maze of people, crowds have always elicited an intense fear. I try to stay away from places jammed with humans. I don’t go to concerts or large events, and if I do, I scan for the exit and position myself next to it. I need a way out, don’t like feeling trapped. You are the same way.

The next day we walk to Josefov, the Jewish quarter, where we visit the Old-New Synagogue. Your grandparents were married here in 1936, three years before Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia. Your dad takes a photo, your cheeks press against mine, your arms around my shoulders. You are taller than me now, something you like to tease me about. Your feet have outgrown your dad’s two sizes ago.

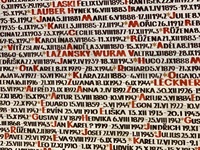

At the Pinkas synagogue we use the computer to search the names of our ancestors, along with 80,000 names of Bohemian and Moravian Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust. When we find their names on the walls, it’s almost like a victory until we remember the horrific way in which they died.

The next day, we take a tour of Theresienstadt where 140,000 were imprisoned, over thirty-five thousand prisoners died, and ninety thousand Jews were sent east to death camps. The guide tells us she’s half Jewish, that her father had family who died in the Holocaust. You put on your headphones and play on an iPad, while I tell her about our ancestors. I usually don’t like when you tune out, but I’m fine with it now. I know it’s going to be a long day. This isn’t my first visit.

I traveled to Theresienstadt with my family in 1994. It’s my mom’s, your babu’s, first time back since she and her parents escaped communist Czechoslovakia in 1968 and came to Canada as refugees. If she had tried to return prior to the Velvet Revolution in 1989 and the fall of communism, she could have been arrested and thrown in jail. I am seventeen years old. I have little patience for my mom’s tears, cannot begin to comprehend how monumental it is for her to reconnect with friends with whom she hasn’t seen or spoken to in almost thirty years. What I do know is that we have no family left to visit. They were killed during the war. I notice a piece of red brick that has fallen off the fortress wall and put it in my pocket. Heart thudding, my insides feel hollow, as if they’ve been chewed up. When I get home, I place it in a box, and bury it deep in my closet.

Two years later, I return to Theresienstadt with my best friend. I am in tears after walking through the collection of children’s drawings from the camp-ghetto. They are beautiful and haunting, scenes depicting the sick and dying but also of expansive skies, birds and trees. Almost all fifteen thousand children deported to Theresienstadt were murdered. This time, I find a stone that shimmers gold and silver, stick it in my pocket, my insides already split open.

When I return nine years later in 2005, it’s with your dad and his parents. I can already feel my heart beating and my stomach lurching leading up to the day we get into our rental car and make the forty-minute drive. After, we go for beers in the town nearby, sit outside at a picnic table in the square. We are quiet, tears stream down my face and splash into my pint.

Fourteen years later, I’m back, but this time I’m with you. When we arrive, the van drops us off in front of a restaurant that is advertising drink specials. I find it strange there are restaurants here. There are also grocery stores and ice cream shops. The sidewalks are clean, and the town is quiet, eerily so. Down one street, a few boys kick a soccer ball. The town feels heavy and depressed. Theresienstadt is inhabited by ghosts. But despite this more people are moving here.

“It’s cheaper than Prague,” our tour guide says. “People like its proximity to the city and they can get a larger apartment for less. A lot of former military people live here now.”

When we enter the Ghetto Museum, we sit down in a small theatre and are shown a film. In it are excerpts from a propaganda film the Nazis used to show the International Red Cross, to fool the world into thinking the Jews and other prisoners were not being mistreated. The film shows images of smiling prisoners, scenes of people in the garden or playing soccer. What the world didn’t see was the death of thousands in Theresienstadt, through starvation, torture and disease. What the world refused to see was the deportations of thousands to death camps.

Halfway through the film, I gasp and squeeze your dad’s leg because I think it’s him. I think I see my uncle Richard, my grandmother’s brother, on the screen. In the film, he’s in the garden, smiling and has his shirt off. He has round spectacles, like I’ve seen in other photos of him, and he’s balding. I am sure it’s him because I have a photo at our house, where he’s chopping wood with an ax, his shirt off, his specs on, his widow’s peak. The photo was taken right before the war. Like all the pictures I have, I am not sure how this one survived, but I am grateful to have it. In that moment, when I think I see my uncle, my insides turn to ice and I have trouble breathing. With each new scene, the narrator tells us about the transports from Theresienstadt to the death camps. On September 6, 1943, my uncle was on Transport Dl, No. 1208 to Auschwitz. He was gassed to death on March 8, 1944. He was twenty-nine years old when he was murdered, the age I was when I gave birth to you. On September 6, 1943, Hana, his wife, was on Transport Dl, No. 1207. She was twenty-three.

After the film, we walk to the gift shop and your dad buys a copy of the DVD. He knows I will need to watch it and re-watch it to make sure the man in the film isn’t Richard. As a member of a family that knows genocide, I am always looking for the living among the dead. When we return home, I find the photo of my uncle, and an old computer with a DVD player, and watch it again and again. I hit pause at six minutes and sixteen seconds so I can stare at the man with the spectacles, the balding head, the naked torso. The man who looks like my uncle. When I finally decide that it isn’t my uncle, I put the DVD away in a large blue plastic box that I keep in my closet with Holocaust books, photos and the rocks from Theresienstadt.

Later after we finish at the museum the tour guide tells us it’s a good time to take a break.

“Is there a place you’d recommend we get a quick bite?” I ask.

Although I’m not hungry, I know I will be. She shakes her head.

“We don’t have much time. There’s a little café downstairs,” she says.

By downstairs, she means in the basement of the Ghetto Museum. We walk down the stairs to a dimly lit cafeteria painted a sickly yellow, with a few round tables and a small fridge. A man who looks like he could have retired twenty years ago, totters out of the kitchen and stands behind the counter. There are neon signs above his head with numbers corresponding to six menu items. I order a burger for you and grab a sandwich from the fridge. It’s the kind of place we know the food is going to be terrible before we order it. When it arrives, the meat (it’s still a mystery) is a shade of grey that looks as old as the Terezin Fortress and is ten times smaller than the bun. You eat a few fries and then bite into the burger.

“I’m not hungry,” you say, pushing it aside.

I sample the cheese sandwich, which has more mayonnaise than either bread or cheese and shove the rest into my backpack. It’s a habit I’ve formed as the grandchild of Holocaust survivors. Body memories of starvation, I store food like a squirrel in winter. Even though this sandwich is nothing I ever want to taste again, I am worried that I won’t be able to last without it, that I’ll run out of snacks before we leave this godforsaken place. The food is nauseating, but it isn’t the reason we feel bad. We feel bad because Theresienstadt is a place of death and we are attempting to nourish ourselves here. Eating in Theresienstadt is like eating in Hades. Once Persephone eats there, she is never the same. Part of her remains in the underworld, with the ghosts. Like me.

When we step outside, it feels like we are transported from the underworld into another form of Hell. You are fascinated by the sign that says Krematorium, a yellow Star of David stamped beside it. I don’t remember being here, inside this place where bodies were turned into ash that fell from the sky like snow. The Krematorium is a lifeless, industrial grey brown. We make a donation for a candle and light it together. You place it with the other candles, on the conveyer belt that used to send bodies into the furnace. There are four black incinerators, with an aisle down the middle. Later I learn that part of the job of prisoners, aside from unloading corpses, was picking through the pulverized fragments of bone to find the gold from the mouths of the dead. At the end of one incinerator, there are three small furnace doors, each large enough to fit a body. It looks like a scene out of a horror movie, the machine full of nobs, gears and buttons, with grey bits of ash breaking out of the opening of the three doors.

I watch you stand between two incinerators, dressed in green shorts and a blue t-shirt, your hair a mess of curls, until I can’t see you anymore because my eyes are a blur of tears. I wonder if we’re messing you up by bringing you here, how many countless hours of therapy you will need after this trip. But then I remember how I needed countless hours of therapy and I didn’t know any of this. Nothing was spoken about when I was growing up. My parents and grandparents kept secrets. I didn’t know that my great-grandfather had taken his life here during my first three visits to Theresienstadt. His body probably ended up in one of these incinerators, the ones you are standing next to right now.

We board the van and the tour guide tells us we’re headed to the small Fortress where the Nazis tortured and executed prisoners, many of whom were part of resistance groups. When the van drops us off, we walk down a gravel path, trees lining either side, and you ask me if I can tell you some of the methods the Nazis used to torture prisoners. When I try to speak, nothing comes out, so I try again, but again nothing. I shake my head.

“It’s okay, Mama,” you say, patting me on the back.

Even though I come from a family that knows genocide, I’m often unable to speak of the violence. I watch you run ahead to catch up with your dad, and I know you are asking him the same question.

We enter a courtyard with yellow buildings. There is barbed wire, and below, black lettering above an archway that reads, “ARBEIT MACHT FREI.” I am familiar with this saying, as are you.

“Work makes you free,” you say.

“Do you know what it really means?” I ask. “That prisoners found freedom only in death?”

You nod and sweep your shoes through the gravel.

“You don’t have to tell me, Mom. I know.”

We walk around the barracks, visit solitary confinement, until I can’t take it anymore. I sit on the steps that face a courtyard where people were shot and wait for you to finish.

When we board the van back to Prague, we talk with the tour guide and then we are quiet. You put on your headphones and I stare out the window, my heart splintering over again into a million pieces. The van drops us off in Josefov and we walk slowly back to our hotel. When we pass a bus stop with a garbage can beside it, I stop to throw out the cheese sandwich, the one made in Hades.

“Hug me,” you say.

You wrap your arm around my shoulder, and I grab your waist and we walk like this in silence. I don’t tell you that watching you stand next to the incinerators almost killed me. How after we return home, I push writing this essay out of my mind for months. How going back to this dark place again would haunt my being, which is already inhabited by ghosts. I don’t tell you that my heart feels punched all the way through, about the way my insides twist, the way my jaw tightens so I can stop myself from crying.

The next day we visit the New Jewish Cemetery and we get lost in a maze of headstones. It’s a beautiful cemetery, with tall trees and ivy lining the graves. You have practiced your speech a few times. We find the headstone of Vilém Lebenhart, your great-great grandfather, who died in 1939, two years before the rest of his family was deported to Concentration Camps. Underneath his name, are the names of your great-great grandmother Klára, your great-great uncle and aunt Richard and Hana, all three of them murdered in the death camps.

Your dad and I sit on a bench and you begin to speak about what it’s like being part of the fourth generation, how many of your friends have large families compared to you, and how you feel sad because of this. You talk about anti-Semitism, how safe and privileged you know you are living in Canada, how lucky you feel to be in Prague, surrounded by the love of your ancestors, and as you speak, I can hear them whispering through trees.

When you finish, my eyes are wet, and we are smiling. You stand before us and we give you a gift. You feel the purple velvet pouch with your hands, run your finger over the yellow stitching of the Star of David. You unzip it and long strands of white tumble out like hair.

“It’s my grandfather’s tallis, his prayer shawl,” your dad says. “Your saba. As you know, he was a survivor too.”

“Thank you so much,” you say.

Your dad helps you unwrap the tallis and together we place it on your shoulders. It fits you perfectly, the white silk draping over you, the blue horizontal stripes hang by your torso, the long white strands hover by your knees. You sit down on the bench in your burgundy polo shirt, your kippah on sideways over your mound of curly hair, grinning, eyes shining like mirrors.

Published in Hippocampus Magazine May/June 2021

___________________________________

Claire Sicherman is the author of Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation (Caitlin Press 2017). Claire speaks and writes about her experience as a third-generation Holocaust survivor and facilitates workshops supporting writers in bringing the stories they hold in their bodies out onto the page. https://www.clairesicherman.

Photo: Ramona Lam

Ray is a 4th-year History Major with a Minor in Germanic studies. With a life-long interest in history, especially in the twentieth century, participation in the Iwitness Field School in 2012, and then a three-month co-op working in the Conservation department of Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum has led to Ray concentrating on Holocaust studies.

I would like to sincerely thank Claire for trusting me with her family history, and for the help she has given me on the way.

I would also thank Claire's son Ben for donating his moving and insightful speech to the narrative.

Thanks also to Jeremy, Claire's husband, for the many images of Prague and Theresienstadt.

Works Cited:

Menachem Z. Rosensaft. God, Faith and Identity from the Ashes: Reflections of Children and Grandchildren of Holocaust Survivors. 2015. Cited in Claire Sicherman, Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation. Caitlin Press Inc. Halfmoon Bay, British Columbia. 2017

Claire Sicherman. Imprint: A Memoir of Trauma in the Third Generation. Caitlin Press Inc. Halfmoon Bay, British Columbia. 2017

For the information in the section Remembrance, Claire used the following resources:

https://www.holocaust.cz/en/

https://www.ushmm.org/online/

https://www.google.ca/