Hester Waas

This exhibit was created in collaboration with Hester's son Richard (Rick) Kool. It will examine how Hester was able to survive the war years as well as touch on some of the experiences she had when trying to reunite with her family and leave the Netherlands for New York after the end of World War II. This page focuses on Hester's story. To learn more about the fascinating way in which Rick uncovered this information click on his name above.

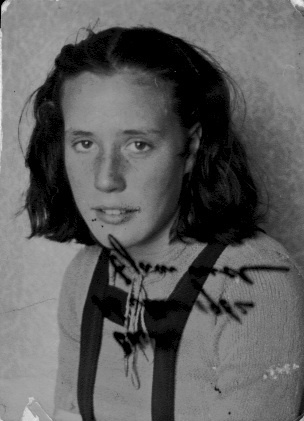

Hester was raised in the beach town of Zandvoort in the Netherlands and was a young teenager when the Nazis were gaining power in Europe. Like a number of Jewish people at the time, Hester managed to survive the Holocaust by 'hiding in plain sight'. Her survival was made a lot easier due to the fact that Hester did not look stereotypically Jewish, notably she had green eyes and light brown hair.

Despite her youth, one of Hester's closest friends, Rosa Cymblast, was already involved with the Resistance. Rosa was the one who found the place for Hester to hide, unfortunately she did not survive the war herself; however, her actions played a crucial part in saving Hester's life.

Another stroke of luck that helped save Hester was when the rest of her family was called up for deportation in the summer of 1942, Hester's name was not on the list. The likely reason for this being that at the time, deportations consisted of people aged 16-45, those able-bodied enough to provide labour for the Germans. Hester at the time was only 15 and therefore likely spared for this reason.

It was sometime in early 1943 that Rosa provided Hester with forged papers and a new name - Helene Waasdorp - so that she could leave Amsterdam and join the family she was to stay with, the van Westerings who lived in Overveen, Netherlands.

Life with the van Westerings

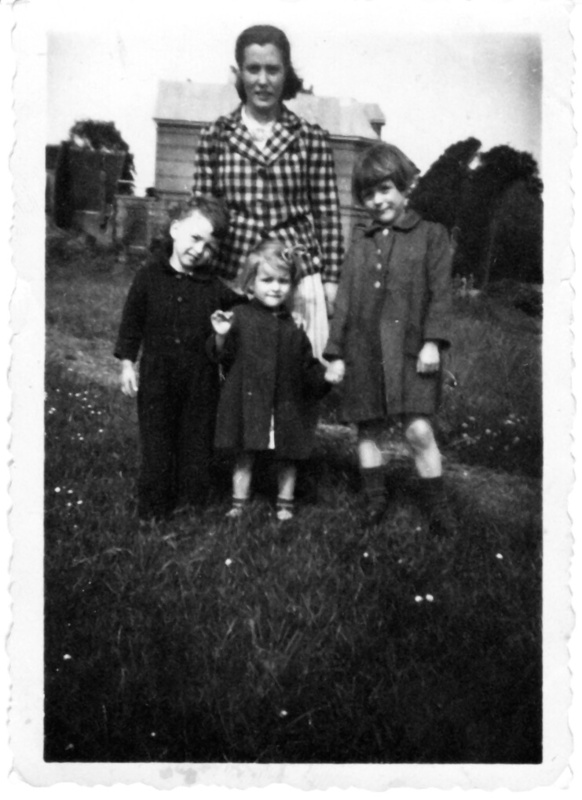

During Hester's time with the van Westerings she acted as the house maid and a nanny for the family's three young children, two of whom were under the age of four when she arrived.

Hester was not the first person to be hidden by the van Westering family, but she was the last and remained with them until the end of the war.

Details about Hester's life during her stay with the van Westerings is very minimal. By the time Hester's son Rick began looking into her past, her own memories were not entirely reliable or even accessible, Mr. van Westering had passed away, his wife did not wish to discuss the topic and the children were too young at the time of Hester's stay with them to remember anything with great detail.

Hester's memories during her time with the van Westerings were those of a lonely teenager. Her brief diary from the early part of 1945 describes her intense dislike of her housekeeping chores for the family, particularly the laundry. In Hester's own memories she remembers having to cook meals for the family but that she never ate with them, and instead ate in the kitchen alone.

She did not have any stimulating social interaction - she rarely talked to Mr. & Mrs. van Westering and the children were too young. She had no girls her age to talk to and was unable to contact old friends either. In conversation with her son Rick, Hester noted that “Even in the camps, people had some social contact with others that you could gripe with and talk to, but in hiding, you had no one to talk to, to share with. I had to bring myself up.”

Complications Rejoining her Family

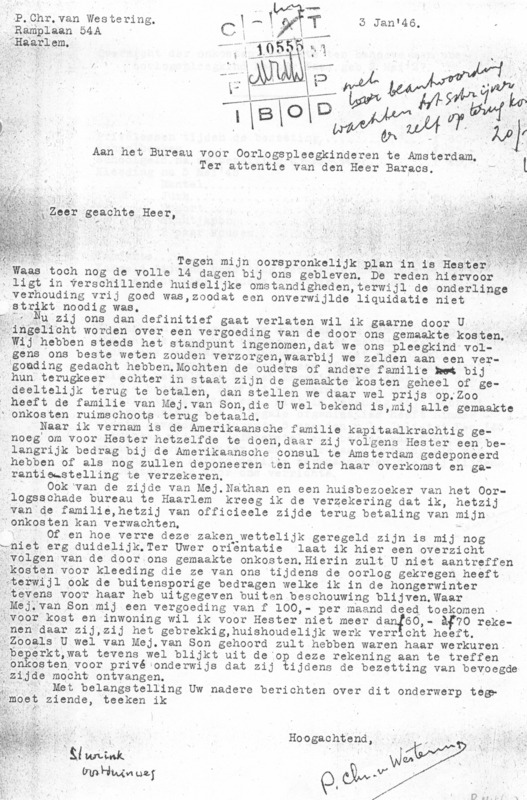

While Hester does not remember details of her departure from the van Westering household, archival documents reveal she officially left the family in January 1946. Her departure was not a particularly happy one, and the documents shed light on a couple of possible reasons as to why. The first was that, after many years in hiding with zero social life, Hester wished to get out, reconnect with her friends and have a social life. The van Westerings though saw her as a needed part of their family through the services she provided. Secondly, the Waas family did not provide adequate communication with the foster family which led to the van Westerings feeling like there was a lack of gratitude for what they had done for Hester. The third reason was that, when money arrived from Hester's grandfather in New York to help her emigrate, the van Westerings saw that the Waas family possibly had the means with which to compensate them for the expenses of keeping Hester throughout the war.

Issues arose due to the van Westerings' treatment of Hester, in which they seemed to regard her more as household help. After the war, Hester's case was dealt with by the Oorlogsplegkinderenbureau (OPK - Office for War-time Foster Children). In correspondence with her social worker, Mrs. Roos, documents indicate the van Westerings referred to her as a maid in a newspaper ad to find someone to help Hester with the housework. They also stated that it was very important to them that Hester receive an education, yet Hester never had time to study because of the number of chores she was required to complete each day.

Hester's grandfather, Abraham TeKorte, whom she wished to join in New York, even wrote to family in Amsterdam that he had sent the van Westerings clothing and other needed materials, but this was never mentioned by the foster family in their correspondence with the OPK.

The van Westerings found issue with the fact that Hester's family was only consulting with her and not with them about Hester's future. Despite Hester being 18 years old at the time, the family, particularly Mr. van Westering, felt they had a right and responsibility to continue to look after Hester's interests even though the war was over. Granted some of the miscommunications may have arisen because of Hester, in a number of letters her grandfather expressed his thanks to the van Westerings, but these letters were addressed to Hester and she never shared them with her foster family.

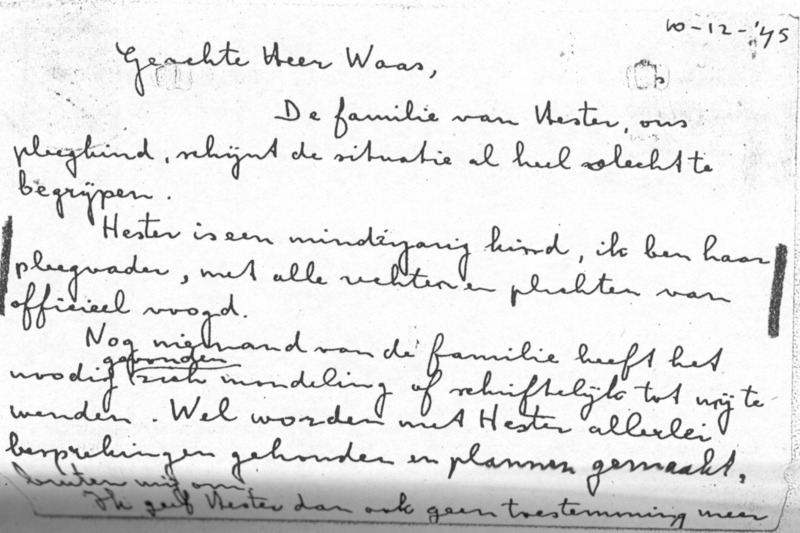

This led to Mr. van Westering writing to multiple members of Hester's family in December of 1945, stating she was not able to visit them as she was needed too much at his home. While the lack of recognition he received from Hester's family was surely upsetting, his refusal to let Hester see her own family did not make the situation easier for any involved.

Lastly, the issue of finances only added to Hester's unhappy departure from the family. As the family's nanny and maid, she received compensation in the form of room and board. Her clothing and other incidentals were purchased for her by the family, but this is not far from what would have happened had the family hired someone as a live-in nanny. It was not till after liberation that the van Westerings expected reimbursement for the care of Hester either from the State or the Waas family.

Information on whether the foster family was compensated for the care of Hester is conflicting. Some documents say the van Westering's received 100 dfl a month, believed to be from the Resistance, during the time Hester was with them, but other documents from Mr. van Westering state this was not the case. After the liberation and the re-establishment of the Dutch bureaucracy, the family received 80 guilders a month as compensation for the cost of caring for Hester.

Mr. van Westering also felt that Hester's family never adequately reimbursed him for caring for Hester because Hester's grandfather, Abraham, had showered Hester with packages; however, we know through letters Abraham sent to Holland that these packages also included gifts for the three young van Westering children, not just Hester. Mr. van Westering also took great offense to the fact that Abraham had sent Hester 2000 dfl; that money was not really Hester's and was meant to help her emigrate to the United States.

By mid-December 1945, Hester had had enough and, taking Mr. van Westering's bicycle, travelled to Amsterdam to be with her family. In conversation with her social worker, Hester revealed she knew her behaviour was not proper but she did not wish to return to the van Westerings. It eventually was decided she would return for two weeks to end her abandoned work properly and this was agreed on by all parties. Mr. van Westering in reality was quite angered that the OPK seemed to be backing Hester and not the foster family.

After her departure in January 1946, Mr. van Westering sent the letter on the left requesting compensation for the care of Hester. The OPK responded that they could not intervene and he should contact the family directly to work out compensation; there is no evidence he followed this advice.

Despite the difficulties that arose between Hester and the van Westerings after liberation, it is important to remember that the van Westering family did offer their home "as an island of safety, surrounded by a sea of risk, danger and death" as Rick puts it. When Mr. van Westering took Hester in, there was also no way to know what would happen by the end of the war, so to say that the van Westerings had been in it for the money all along would be false. Rick is sure to never downplay that without the aid of the van Westerings, Hester and her children, including himself, would not be alive today. In 1995 Rick went on to nominate Paul van Westering for an award through Yad Vashem for his role in the saving of not only his mother, but also the other Jewish people who passed through his home before Hester.

"I spoke of the need to remember the six million, but to remember also those whose actions ensured that the number was not six million plus one". -Richard Kool

Behind the Exhibit

I (Michaela Sawyer) worked with Richard Kool in order to complete this exhibition. I am a first-year Holocaust Studies masters student and have been interested in World War II and the Holocaust since 2011 when I went on a two-week trip to Europe led by my high school's history teacher. Her passion for history and museums sparked that same passion in me. I went on to complete a Bachelor of Arts with a Joint Major in History and World Literature, as well as a Diploma of Cultural Resource Management before beginning this masters program.

Choosing what to focus on for this exhibit was a difficult task; there are so many aspects of Hester's story that are all so incredibly interesting. In addition, Rick's side of her story was also fascinating and could not go unacknowledged. To hear Rick talk about his mother's story as well as his own was incredibly moving, but to hear the respect he holds for the man who saved her is something else entirely. Even though it is very apparent his mother struggled during her time with the van Westerings, Rick's gratitude for their efforts and his appreciation of the efforts of the people who, as he puts it, "kept the number from being six million plus one" is equally as moving to hear. It was an honour to meet Rick and hear not only his mother's story but his as well, and I hope I have done them both justice. Thank you.