Micha Menczer

My Father’s Stories

Dedicated to the memories of Mottel Menczer (z’l) and Regina (Dermer) Menczer (z’l)

My name is Micha Menczer and I am proud to introduce this digital exhibit entitled “My Father’s Stories”. My parents Mottel Elieser and Regina Menczer were survivors of the Holocaust or in Hebrew, the Shoah. My first name, Micha, honours my paternal grandfather Mechel Menczer. My middle name Jacob honours my uncle Yakov Dermer. Both men died in the Shoah.

This exhibit chronicles my family’s lives before deportation to a concentration camp in Ukraine, life in the camp, their journey home after liberation, slow emigration to Canada and their early lives as immigrants in Canada. It is not a comprehensive history but a story of what I learned from direct witnessing by my family. While the details of my family’s story are specific to them, the story is shared by thousands of Jewish families.

Although historical records are an essential part of remembrance, the numbers–6 million killed–and graphic images of bodies and death camps can be numbing. Instead, I would like to bring those statistics to life by sharing my family’s story using photos, documents, oral history from talks with my mother and cousin Nelly and, most poignantly, my father stories written in Yiddish. I ask you to look beyond numbers of Jews killed and think of individuals and families like mine, with hundreds of years of vibrant life in Europe, contributing to society through music, arts, literature, academia, medicine, law and business. These were people whose lives were shattered by terrible times.

While my parents were victimized by hate and cruelty, they were not victims. They were extraordinary people. They taught me, in words and by example, openness, generosity and respect for all people. I am sharing their story to make the Shoah more real for you. While mourning those who died, please recognize also the courage, strength and resilience of survivors like my parents who rebuilt their lives in countries like Canada. I believe commemorating the Shoah in this way makes remembrance more meaningful and truly respectful.

I dedicate my participation in this exhibit to my parents Mottel and Regina Menczer.

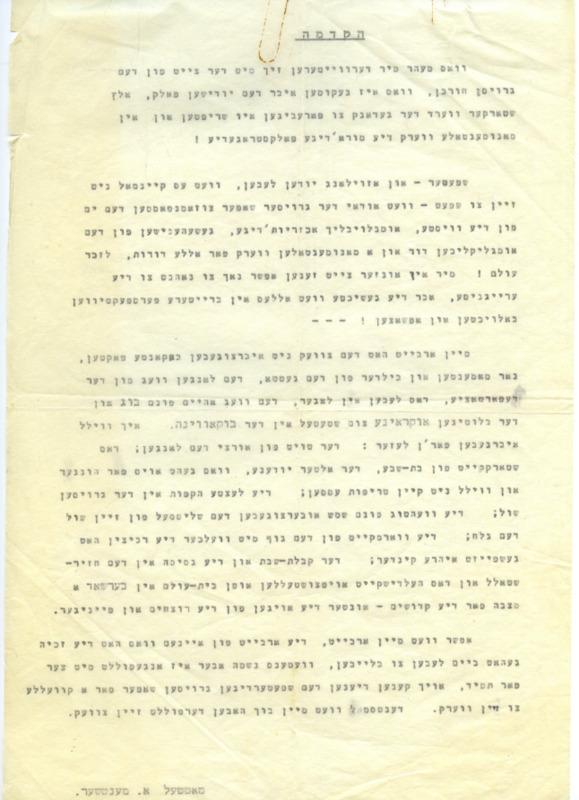

Preface

Mottel Menczer

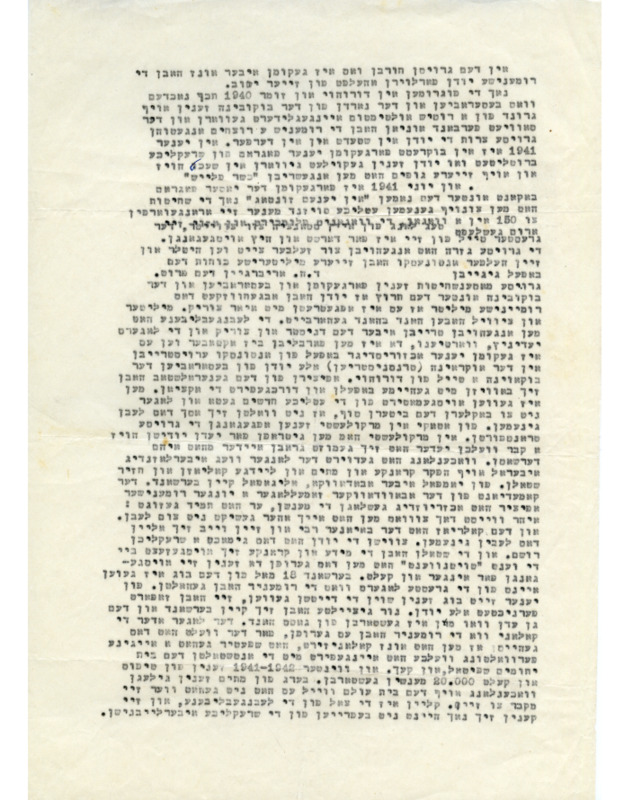

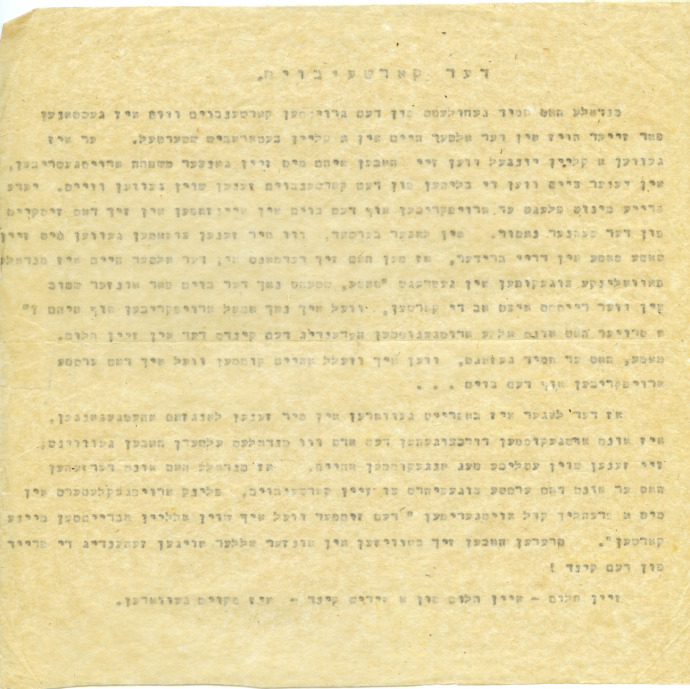

The further we distance ourselves, as time passes, from the great destruction which came over the Jewish people, so grows the desire to commemorate in a monumental work, accounts of the devastating tragedy of the people. Later on, in the future – as long as Jews are alive, it will never be too late. The Almighty will certainly bring together the sea and the wasteland to reflect the unbelievable cruelty. The events of that unfortunate generation demand a monumental work to serve as an everlasting memorial for all generations. We, in our time, are perhaps too close to these events, but the happenings will be illuminated and evaluated in a broader perspective.

The purpose of my work is not to inform about known facts, only to describe moments and pictures of the ghetto, the long journey of the deportation, life in the camp and the way home from the Bug in the muddy Ukraine to our hometown in Bukovina. I want to relate to the reader: the death of Ortzi der Langer; the strength of Bat Sheva; the old Jewish woman, who is dying of hunger, yet refuses to eat non-kosher food; the last Hakafoth in the Great Synagogue; the pain of the shamas (caretaker) on handing over the keys of his synagogue to the priest; the warmth with which the Rabbi’s wife fed her children; the welcoming of the Sabbath and the death of those in the big barn, and the heroism to erect, at the cemetery in Bershad, a monument to the martyrs, under the very eyes of the torturers and murderers.

Perhaps my work, the work of one who was privileged to remain alive, but whose soul is filled with everlasting sorrow, may also serve later on, the creator of a bigger work, as source material. Then my book will have fulfilled its purpose.

Life Before Deportation

Introduction by Micha Menczer

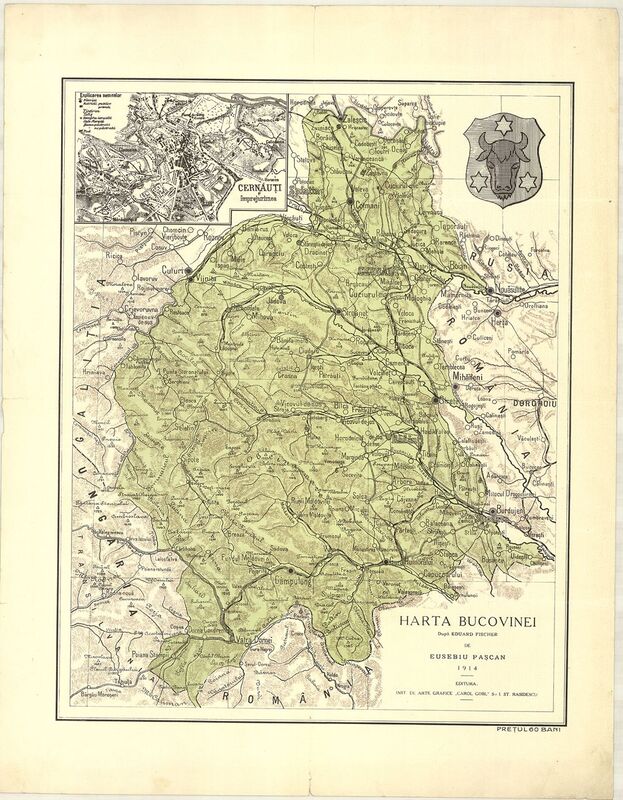

My parents were both born in villages or shtetls near the city of Chernivtsi in the province of Bukovina in eastern Europe in the early 1900s. Chernivtsi was the largest city in the area and a vibrant business and cultural centre. When my parents were born it was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire but after the First World War this region became part of Romania.

Both my parents came from large and extended families. I do not know a lot about their history but will share what I do know to provide a picture of their life before the Shoah. The Menczer family had been in the shtetl of Storozhynets for countless generations and were well known and respected. My grandfather operated a dry goods store and was very active in the Jewish community in Storozhynets.

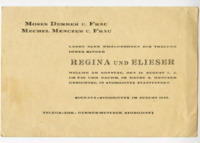

My father went to Vienna and studied at the Wiener Handelsakademien (Vienna Academy of Commerce) and after graduation returned to manage the store; however, his passion was writing and politics. With others in the labour movement he was an active Zionist for the creation of a new state, Israel. His sister and brother emigrated to Palestine in the early 1930s, and I believe had circumstances been different my father would have followed. My father married my mother Regina Dermer in 1935 and their wedding invitation is part of this exhibit.

My grandfather Mechel Menczer died before the war and was spared the pain of deportation and deprivation. He was also spared learning of the murder of his daughter and son-in-law by the Nazis and the narrow escape of his grandchildren in Vienna. My grandmother’s death just before the deportation is described in the story Bat Sheva.

The Dermers, my mother’s large family, had been living in the shtetl of Suceava in Bukovina for many generations. Yakov was eldest of nine children of my grandfather Moses (Moshe) Dermer who was a farmer. Moshe’s children despite the family’s subsistence earnings were engineers, teachers, business managers and medical school graduates. My mother graduated from college and became the executive secretary to a non-Jewish, Romanian baronial family managing extensive farm and business holdings, a remarkable position for a young Jewish woman in those times.

From what I have heard, my parents had rich and meaningful lives before the war with a large circle of friends and family, enjoying concerts, lectures, lakeside holidays, lively political and social discussions with friends and more.

Deportation

Introduction by Micha Menczer

Life for my family and Jewish families throughout Europe changed dramatically in the late 1930s as the Nazis and their ideology took hold, not only in Germany but also in countries like Romania.

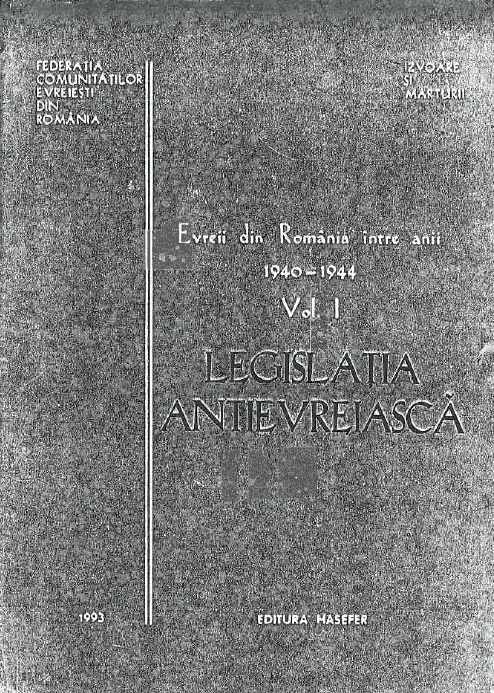

The Romanian laws from that time shown in this exhibit exemplify the tightening restrictions on Jews in Romania in the late 1930s and early 1940s. In 1940 Storozhinets was occupied by Russian forces, which controlled the region until the spring of 1941, after which the Nazis seized control of towns in Bukovina and forced Jews, including my parents and their families, into ghettos. My great aunt Tante Gusella’s description of the situation in June 1941 as told by my cousin Nelly was “Die Situation ist verworen” meaning “the situation is muddled.” An apt but under-stated characterization.

As conditions worsened it was apparent more dangerous times were coming and deportations were likely. Because of my mother’s position with the high-standing Romanian family, she was told they would protect her and my father from deportation even though it was a considerable risk to them. My mother asked, “What about the rest of my family?” They told her while they would like to help the others, it was “pushing the edge” to keep my parents from deportation and it was not possible to protect others. My mother replied that she would stay with her family and deal with what came.

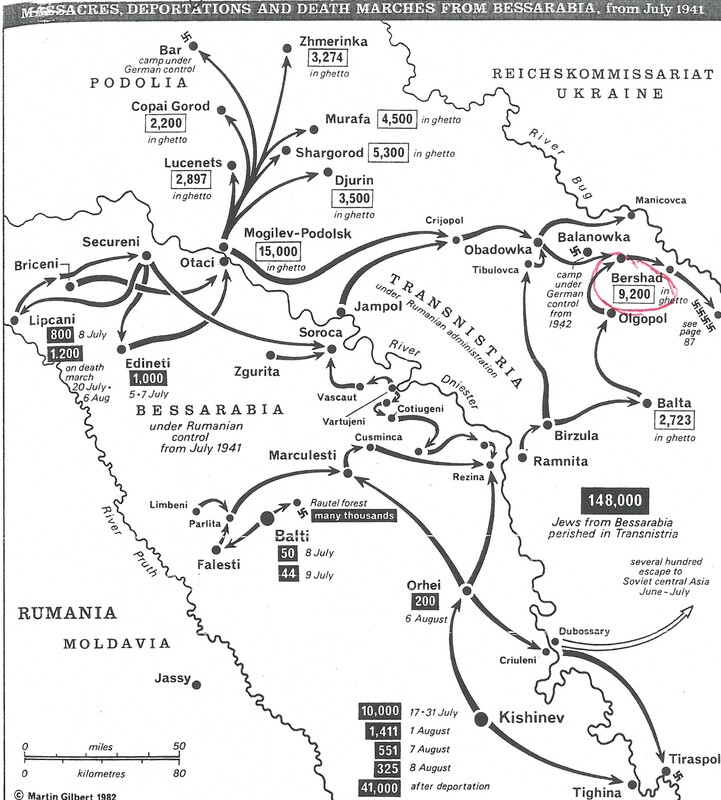

In November-December 1941, Mottel, Regina, Yackov and Laura Dermer and daughter Nelly, Moshe Dermer (Regina’s father), Zunia Rettig (Laura’s relative) and her fiancée pharmacist Spiegelman, Tante Gusella, Yosef Menczer (my father’s cousin) all were deported to Bershad Camp in the Ukraine. They suffered terrible conditions on the long journey by foot and cattle car over several weeks covering more than 300 kilometers. The map in this exhibit shows the deportation route and my father’s stories “The Night in the Forest”, “Hakafot” and “Epilogue” chronicle his first-hand experiences.

Told they were being taken to a work camp, my mother did not believe this, but still was a strength for the family, as she was later in the camps. My uncle Yackov being a student of history said, “they don’t take you hundreds of kilometers from home to work. This is a death march,” and he succumbed to the brutal conditions on the march.

Bat-Sheva

Mottel Menczer

She was 78 years old. She lived her life in piety; she was dedicated in her service to the Creator, so much so that she sacrificed her health. She had been ill for a long time, but probably this is the way it is supposed to be. "But enough," she pleaded with the Almighty. When the war started, she was already paralysed.

In the shtetl, there were bitter rumours, people already knew that the shteti would be returned to Romanian rule. They always feared the transition. The Russian authorities gave the order that part of the population of the town was to be evacuated, as they had placed dynamite to destroy the town's electrical power station. In my plight, I took her to the hospital, where a relative of mine worked. This seemed to me to be the safest place for her. I did not see her alive anymore. Her physical power was weak, but her mental powers were sharp.

In her life, she had observed the dietary laws of Kashrut, so she refused to partake of non-kosher food. After four days of not eating, she died. Her spirituality overcame the physical life.

For eight days, she lay in the morgue, until I received permission from the Romanian authorities to bury her. When we arrived at the cemetery, the dog catcher, who was the owner of the deserted city, brought out 200 corpses, people who had been shot by the killers a few days before, and whom he threw into a mass grave. I dug a grave for my mother, to bury her in a separate grave, next to my father, may he rest in peace. Thus at least one part of her will was fulfilled.

With pure thoughts, she went over to the next world – to her world of Truth...

Hakafot

Mottel Menczer

We all remember Hakafot [the annual celebration of the completion and immediate beginning of the Torah scroll reading] with flags and red apples on them. We went with our fathers to the Hakafot ceremony. Later, when one grew up, one practiced the belessings of the Torah; then, as a lad, one received the Hakafah honour for oneself, and then later still, one would take one’s own children on the same path – the path of the Golden Chain.

But these Hakafot were entirely different, joy and light and sparkle were absent. For two days already, it was known in the ghetto that the Romanian power was about to deport all of the Jews of the city, who had been there for generations, to the bloody Ukraine. At the train station, there standing ready, were the cattle cars – on Simchas Torah they would leave their homes.

Our cantor, Reb Chaim Lerner, was a tall Russian Jew who served the synagogue with great devotion. His davening [praying] had called on the congregation forcefully that we should go with the Hakafot and say farewell to the Holy Scrolls.

The synagogue was dark. Jews no longer had electricity; there were several small candles in the large synagogue. The cantor reads the prayer Ata Horaisa. The scrolls are taken out of the Holy Ark, and the two quorums of Jews go around with broken hearts and bitter wailing. We feel something frightful, and we cannot tear ourselves away from the scrolls. So, wailing, we clutch the Torahs close to our hearts as we come to the end of the Hakafot ceremony.

With the scrolls of the law put back into the Holy Ark forever, the synagogue was locked up. The Shamas Meyer [caretaker] gave the keys to the synagogue, which he had helped bring into being, and with deep sadness gave them to the priest. With this handing over of the keys, the Shamas gave away a part of his soul.

On the first section of the long journey to Edineti, Meyer departed this life.

Four years later, I returned to that synagogue – there was no Holy Ark, no scrolls of the Torah – all that remained was a simple warehouse.

The synagogue stands desolate, and weeps and weeps…

The Night in the Forest

Mottel Menczer

We were taken not over the main roads but over muddy fields and forests purposely to make the bitter journey even more difficult. It was already dusk when they forced us into a forest - the Kasutza Forest. Every group of those deported was given the sad honour of spending the night there. The night was truly a nightmare - it poured rain - one could not even make the smallest fire to warm your soul. We had no food - all over the place there were dead bodies from the previous group of deportees - this was the way we spent the unforgettable night shivering in the cold. The driving rain did not stop the Ukrainian hooligans from attacking and robbing us and each time we heard new cries for help.

In the morning when we prepared to go further there lay beside us a child wrapped in rags who was still breathing. Did a mother leave him here? Who's to know, perhaps she herself did not survive the night. A Jewish mother would not leave a child alone. The group of those deported were further pushed on - a child more or less - who asks for an accounting?

Journey Epilogue

Mottel Menczer

In the great catastrophe that overcame us, the Romanian Jews lost half of their population.

After the pogroms in Dorohoi in the summer of 1940, when Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina were incorporated into the Soviet Union on the pretext of an ultimatum from the Russians, the Romanian murderers caused much suffering to the Jews in the cities and villages. In January 1941, in Bucharest there occurred a pogrom of extreme brutality where Jews were slaughtered in slaughterhouses and on their bodies was written “Kosher meat”.

In June 1941, the Iasi pogrom known by the name “On that Sunday'', took place. After the massacre, they rounded up several thousand men, threw them into box cars with 150 to each car; they locked the doors and drove them around for days, from one station to another. The majority perished from thirst and heat. At this time Hitler and his ally Antonescu sent an order to their military forces to cross the Prut river. Great mass murders took place in Bessarabia and Bukovina, with the excuse that the Jews humiliated the Romanian army when they had retreated the previous year. Military and civil authorities worked hand in hand. The survivors of the massacre were driven across the Dniester river to the Yedinetz and Vertijeni camps. Here they remained until October, when the vicious order came from Antonescu to drive them to the Ukraine (Transnistria) – all the Jews from Bessarabia, Bukovina, and part of Dorohoi. Officers of the General Staff brought secret orders and carried out the action. The Jews were too exhausted after several months in the ghettos and camps to understand what lay ahead; many would have committed suicide if they had in fact comprehended the bitter end that awaited them. From Ataki and Marculesti, the large transports departed. In Marculesti they found for every Jewish house, a grave, which the Jews had to dig for themselves before they were shot. The long journey lasted weeks, abandoning on the way the sick and the dead with no one to care for them; also emptied were Kolchozs (collective farms) and pig stys. From Yampol to Abadovka, Eligafal to Bershad, the Commandant of the Abadovka “assembly” camps, a young Romanian officer, cruelly beat the people and always told us, “You know why you have been sent here; and it's not to stay alive”.

The Boyaner Rabbi and his wife committed suicide, which left a terrible impression on the Jews. In the barns, the weary and the sick settled themselves around the walls, known as the “death walls”. Here they perished from hunger and cold.

Bershad, 18 miles from the Bug river, was one of the largest camps the Romanians had under their control. When the Germans reached that side of the Bug, they immediately massacred all the Jews. Only a few rescued themselves in Bershad, in the “Garden of Eden”, where they died of natural causes.

The camp was known by the Romanians as “the Colony”, because for the outside world it was as if they had colonized it. Later it had its own administration which managed institutions like the orphanage, hospital, and soup kitchen.

In the winter of 1941 to 1942, 20,000 people died of typhus and the effects of the cold [in Bershad]. For weeks, mountains of corpses lay in the cemetery; there was no one to bury them. The number of survivors was small, and they could not free themselves even today of the shattering experience they survived.

Bershad Camp

Introduction by Micha Menczer:

Bershad is a small town in the Ukraine where Jews have lived since the 1600s. During the war it became the biggest of the concentration camps in the area and by all accounts the one with the worst conditions.

The ghetto in Bershad, where my family and thousands of other deportees from Romania were sent, was a small area in the centre of the town surrounded by barbed wire. The camp consisted of small houses on twelve narrow streets and two main streets. Into this confined area some 20,000 Jewish deportees, including my family, were pushed and held for more than two and a half years. They were imprisoned and denied the basics of life with only minimal food and clean water. Simply stated, Bershad was a ghetto camp bursting at the seams and characterized by typhoid, starvation and random killings by the guards. From September 1941 to August 1942, more than 15,000 people died in the ghetto.

The first winter in Bershad was freezing and harsh and my grandfather Moshe (my mother’s father) was among many who died. While there is no written story, I recall my mother telling me of my father going around the ghetto bartering what little they had to get a respectful burial for my grandfather. I learned of this and other stories of their experiences in Bershad from my father’s writings, my mother’s recounting of experiences and long discussions with my cousin Nelly who later married and settled in the United States.

My father’s stories “Burn the Camp, Shoot Them” and “The Gangster and The Angel” are records of life in Bershad. (“Burn the Camp, Shoot Them” has an interesting allusion to Queen Esther in the Purim story demonstrating my father’s ability to make a connection between biblical stories and events in Bershad.) He wrote several other stories documenting unimaginable and horrific circumstances through the eyes of one who lived through them. The final story in this section, “The Monument,” describes the actual memorial at Bershad cemetery. The memorial is remarkable because it was somehow built in 1943 by camp inhabitants outside the camp itself.

Sadly, my father passed away when I was nine, so I never had the chance to talk with him about these experiences and how they managed to survive physically and emotionally while so many did not.

Stories my mother and Nelly told me after my father’s death are, in addition to my father’s writing, the main source of information about my family in the camp. One story described the sad and almost humourous image of my mother in a scavenged and hugely oversized coat and size twelve men’s shoes picking lice off Nelly’s hair. Another told of the dangerous passing off of my father as a typhoid-riddled old woman in a “baboushka“ huddled in rags when camp guards came looking for men. I heard about my mother’s brave trips to the barbed wire fence, known as “the wire,” to receive smuggled food sent by family in Bucharest who had avoided deportation. My mother and Nelly also told me of my father’s best friend, lawyer Michael Shrenzel, coming out of hiding when guards, searching for those who organized a resistance, threatened to kill people at random. Michael Shrenzel was never seen again. These are a few of the many stories I could share.

My mother spoke not only of their hardships during the Shoah but also of the bravery of non-Jews who risked their lives to come to the wire at night and bring food, knowing full well that if they were caught they would be immediately killed. She told me as well of the priest in Bucharest who did not reveal my uncle and aunt living next door when Nazi guards searched the neighborhood.

The history of my family in the Bershad Camp reveal a tragedy created by cruel and hateful ideology, but also the bravery and strength of my parents and the decency of those who helped them.

Burn the Camp! Shoot Him!

Mottel Menczer

In the third year of our life in the camp, the partisan movement along the Bug river increased significantly. The partisans caused a lot of trouble for the Germans and the Romanians. Every day there were new victims of the murderers.

Once the murderers caught a young Ukrainian woman, and from her they learned of a connection between the partisans and the camp. She was tortured cruelly and then shot. Later on, they arrested five Jews, in the same connection to the camp. After a month, they were shot. At that time, the Commandant, a high-ranking Romanian officer, found himself in the surrounding forest with a company of soldiers, to fight against the partisans. When he was told of the connection between the partisans and the camp, he simply sent an order from the forest to immediately ignite and burn the camp. Only a few people found out what danger hung over the camp at that moment.

Our leader – a very dedicated and committed person, moved worlds, and late at night he succeeded in averting the disaster. The deputy of the Commandant had, that night, a beautiful, golden dream and so the people were saved.

After a while, the Commandant returned from the forest. Of course, he no longer had a good feeling about the camp. Once, after a night of heavy drink, “When the king’s heart was happy with wine”, he called in our leader. When he arrived, the Commandant ordered his personal assistant to, “take him out and shoot him”.

At the drinking party, there was a Jewish girl from the camp who overheard his order – “Burn the camp! Shoot him!” She threw herself at his feet, crying and begging him. With her crying and begging, “Esther” saved the camp from the Commandant’s murderous hands.

So the camp was once saved from a great danger; the second time, the Jewish camp leader was saved by a coincidence.

The Gangster and the Angel

Mottel Menczer

The head of our camp was a young Romanian officer, a 24-year-old, who had graduated from the military school in Germany. He was such a rabid Anti-Semite that he did not want to take any money from Jews or to have an association with Jewish girls, unlike the other officers. He wanted to make the camp an example and chase out the Ukrainian and Bessarabians whom he regarded as communists. There was a serious battle between him and the head of the camp, who knew that this would mean death for unfortunate victims.

He already had had the order to remove them from the camp and began to register them. He could not understand why there was so great a struggle to stay together. We are all brothers, regardless of where we came from, said the head of the camp. He was not successful in implementing his devilish plan and was only thinking of how to make the life of the people more miserable. He dug a trench around the camp so that the Ukrainians could not visit and sell their food. When he found a Jewish boy outside the camp, he tied him up to his motorcycle and dragged him to the head office.

After liberation, he was caught and after a long legal process in Bucharest, he was sentenced to death; later the sentence was converted to life imprisonment.

The opposite of him was another Romanian officer, who said that his mother told him to treat the unfortunate camp Jews well. When the Germans wanted to transfer the camp across the Bug river, he found an excuse to prevent it by stating that there was a typhus epidemic and the disease would be spread among the general civilian population. In this way he saved thousands of people from certain death. He always counselled us that we should remain together and help each other until liberation. The whole camp loved him. The children used to run after him. For his “too” good behaviour to the Jews he was exiled to a small village by the higher authority. With tears in his eyes he parted from the Jews, accepting a small present from them.

A great deal of suffering and misfortune would have been spared us, if the good angel had been with us to the end.

Translated by Shia Moser, Sheila Barkusky and David Shaffer

The Monument

Mottel Menczer

On the sandy earth of the Bershad cemetery, in the middle of the largest mass of graves, where tens of thousands of martyrs were laid to rest, there stands a tall monument, erected under the very eyes of the tormentors to the eternal memory of the destruction of the eternal people.

The survivors, with sadness and frustration in their hearts, hungry and ragged, in the very place of their tragedy, in the valley of Destruction, erected this monument as a message of lament.

The people of Bershad, among them Professor Yosef Levi of Chernowitz, carried out the work. The Rabbi of Britzner, Berel Yostner, had written with fiery letters the way that they lived and died.

(In Yiddish) In eternal memory of the destruction of their worlds,

From the Eternal People for Eternity

In the valley of their tragedy, there shall be no rest.

The pain and suffering of tens of thousands of Jews.

Fathers and sons, children and revered old people,

In the mass graves, not separated one from the other.

Killed by suffering, frozen in the cold.

Martyrs of the Dispersion robbed of their freedom.

Martyrs of the people – who knows their secrets?

In Life as in Death- “hammered” together

“May their souls be bound in the blessing of life” Bershad – 1941-1944

(In Hebrew) In everlasting memory, everlasting destruction of the world. For the Eternal People – for all time. The Valley of the Destruction

The agony of the masses of the people of Israel.

Without kin and redeemer. Sons and fathers, children and respected elders.

In mass graves, together – not divided. They died – victims of the sword and the cold. Wanderings of the Diaspora; robbed of freedom Martyrs of the Land; victims of a tyrant. In their lives and in their death they were united.

Bershad –

1941-1942

May their souls be bound in the blessing of Life.

Journey Home

Introduction by Micha Menczer

In 1944 the Russian forces pushed back the Nazis and Romanians and recaptured many parts of the Transnistria region, including Bershad. When the Red Army liberated the Bershad camp in March 1944 there were about 10,000 Jews still alive. My parents, Aunt Laura and cousin Nelly were among them. News had trickled into Bershad of the advancing Russian army and my parents decided to leave the camp before the Russians arrived. There was a fear that my father even in his weakened state would be taken into the Russian army and would not survive. As a result, my parents left the camp despite the dangers of ongoing fighting to slowly make their way home.

Mottel’s story “The Way Home” describes this arduous journey and their return to Storozhynets, his hometown, where the pain of seeing the destruction was so great that they could not remain there. My parents went on to Bucharest where some of my mother’s brothers lived and through good fortune had avoided being deported during the war.

There were in my father’s stories reminiscences with more optimism. His story “The Cherry Tree” is a story of hope and resilience. It describes the touching moment of young Mendele from the camp being once again able to climb his favourite tree at home which, like him, had survived ravages of war. I read this story to students and at Shoah commemorations to remind people of the courage, strength and optimism of the survivors and their determination to rebuild their lives.

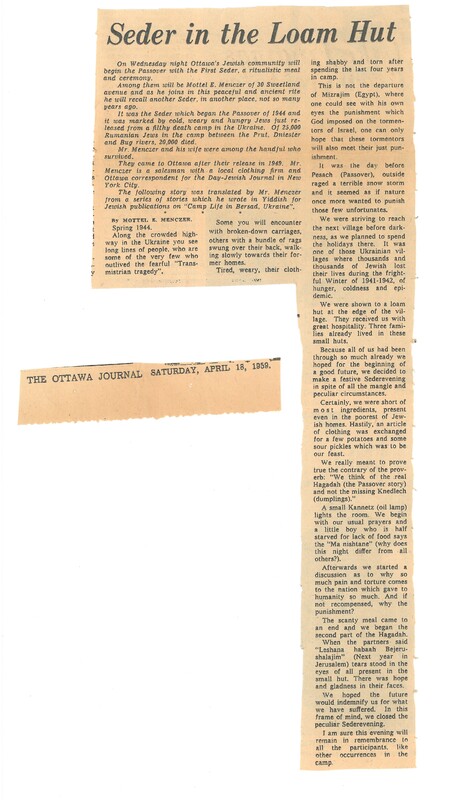

As the fighting was still raging in the spring of 1944, my parents and others had to move slowly behind battle lines on their way home and stop in abandoned villages for periods of time. They lived in sheds, barns, burnt-out buildings and ate whatever food they could barter for or find. My parents, despite all they had gone through, fiercely held to their identity as Jews and while not religious recognized the significance of Jewish rituals and holidays. My father’s powerful story “Seder in the Loam Hut” provides a moving description of a Passover Seder held in these extraordinary circumstances almost as a statement of “We are still here.” It was published in the Ottawa Journal newspaper in April 1959 seven months before he died. I often wonder had he lived longer how many more of his stories would have received a wider readership.

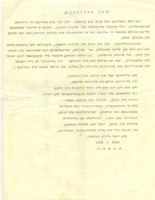

The last document in this part of the exhibit is a story in itself. My father’s stories were written in Yiddish. I had translated some with the assistance of my cousin Dora Steininger (Speigel). Dora barely escaped the Nazis as a teenager with her brothers from Vienna but tragically her parents (my father’s sister Pearl and husband Moshe) were deported and killed by the Nazis. . After translating some stories with Dora, several more remained. I was living in Vancouver and asked some people I knew who read Yiddish to assist me. I am very grateful to David Schaffer, Shia Moser and Sheila Barkusky who translated several stories.

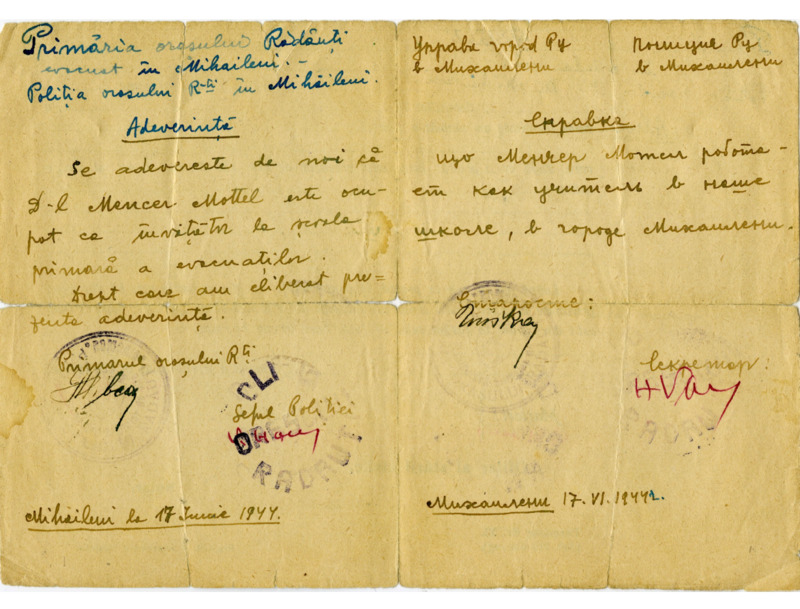

Among my parents’ papers, in addition to the stories, were numerous documents some of which are shown in this exhibit. Among them is an unusual “Certificate” in Romanian dated June 17, 1944. After the translations were complete, David Schaffer asked to meet me. He told me that this document stated that my father had been a teacher for a time in 1944 in Mihaileni, Romania. I was surprised as this had never been mentioned by my mother.

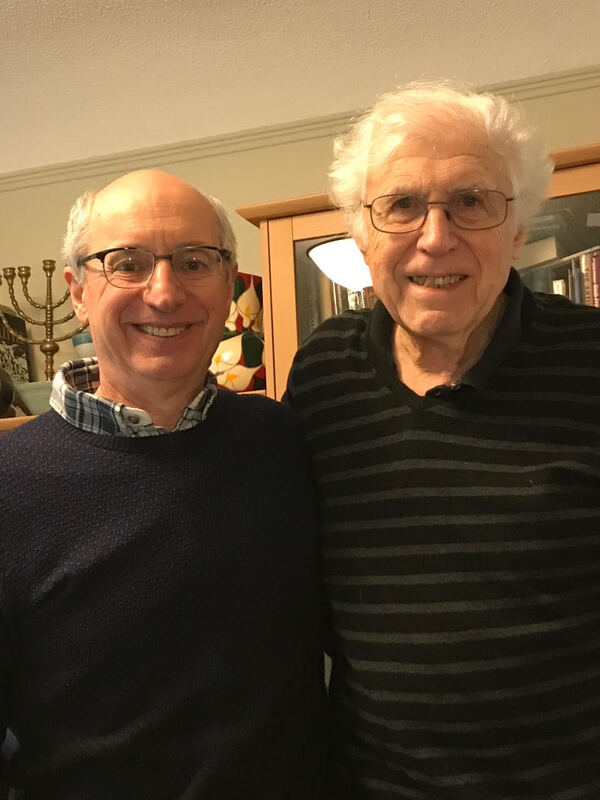

David informed me that a group of Jewish refugees had stopped in the Mihaileni/Radauti area waiting for fighting to ease so they could return home. Several of them decided to start a makeshift school for the young children with them. The “Certificate” attests to my father’s role as a teacher in that school. When I asked David how he knew about this, he told me he had been one of the students in the school! My jaw dropped when I heard this. While David did not know my father, he told me in detail about the school and his own wartime experiences. David’s story in itself is remarkable and one that has been well documented. Our continuing friendship is one of the legacies of “My Father’s Stories” project.

The Way Home

Mottel Menczer

Weary and tattered after approximately four years of living in a camp, a small group who survived started again walking on the same route home. Each one left behind in the Ukrainian soil a father, a mother, a sister or brother, a wife, or children.

Days and weeks we continued, with time to think about everything, recalling the various stages of the events. Long rows of people stretched – one carrying a broken children’s stroller filled with “rags”. Another carrying a small child, thanking God for sparing his child from loss. Another is carrying a nice little boy who had suffered frozen feet in the “kolkhoz” – collective farm.

Here an elderly Jew, a former merchant, who the Germans with a transport of several thousand dragged across Bug river. About one hundred survived, miraculously. He never tired of telling his survival experience.

We were approaching a hill, near a tree a grave; here a friend had buried his mother – not so, she was merely covered up in a hurry.

“And they buried them on the way.”

Six hundred Jews died from our town. Only twenty-five survived. The Rabbi with his entire family of ten members. At an open well, a desperate father jumped in, his wife and two children survived in spite of it all.

Nearing the Dniester river at Yampol which took in into itself so many Jewish victims, one had to steal oneself over a damaged bridge. On the other side of the river was Bessarabia. In a little village where twenty Jewish families lived, nineteen of them were killed, a Jew leads a cow, which he had retrieved from a robber.

There lives Azriel, who had been a respectable homeowner, was in the camp a tattered beggar. Today he is begging someone to allow him to stay for a few days. Now, thank God, he is back in his home with his empty rooms, but on his own soil. We reached the Prut river and one had to steal oneself across the bridge at night. Why? Only those who experienced this would understand.

Five weeks later, after wandering, I reached my shtetl – little town. It is Shabbos afternoon. I go out with my friend to look around. Nature has not changed, beautiful green fields, the little forest near the town, but the people are absent. We search the synagogue; all is destroyed. The Holy Ark and Holy Books are gone. The bank and the Christian pubs – the Rabbi’s house destroyed. Across from the synagogue lived Reb Abraham, a learned Jew, and a cantor who used to lead the prayers at the synagogue. On the road, robbers dragged him into the forest and killed him. Here was the Hebrew school where two hundred people studied with pleasure. Today it is burnt, pain surrounds everything, and hot tears are flowing. The next day, we went to the cemetery, which had remained untouched because the murderers had no dominion over it. The dead, our beloved ones, with two mass graves after the last killings. We stood for a long time by the graves of people from another world – it was hard to tear oneself away.

The cemetery is no longer alone – added to it was another big one – the whole destroyed city, which became a second cemetery. I left my shtetl soon after; I cannot live here anymore. There is no space; no air for my soul – I am choked and I run away to look for a new home.

Seder in the Loam Hut

Mottel Menczer

Spring 1944. Along the crowded highway in the Ukraine you see long lines of people who are some of the very few who outlived the fearful “Trans-nistrian tragedy.”

Some you will encounter with broken-down carriages, others with a bundle of rags swung over their back, walking slowly towards their former homes.

Tired, weary, their clothing shabby and torn after spending the last four years in camp.

This is not the departure of Mizrajim (Egypt), where one could see with his own eyes the punishment which God imposed on the tormentors of Israel, one can only hope that these tormentors will also meet their just punishment.

It was the day before Pesach (Passover), outside raged a terrible snow storm and it seemed as if nature once more wanted to punish those few unfortunates.

We were striving to reach the next village before darkness, as we planned to spend the holidays there. It was one of those Ukrainian villages where thousands and thousands of Jewish lost their lives during the frightful Winter of 1941 – 1942, of hunger, coldness and epidemic.

We were shown to a loam hut at the edge of the village. They received us with great hospitality. Three families already lived in these small huts.

Because all of us had been through so much already we hoped for the beginning of a good future, we decided to make a festive Seder evening in spite of all the mangle and peculiar circumstances.

Certainly, we were short of most ingredients, present even in the poorest of Jewish homes. Hastily, an article of clothing was exchanged for a few potatoes and some sour pickles which was to be our feast.

We really meant to prove true the contrary of the proverb: “We think of the real Hagadah (the Passover story) and not the missing Knedlech (dumplings).”

A small Kannetz (oil lamp) lights the room. We begin with our usual prayers and a little boy who is half starved for lack of food says the “Ma nishtane” (why does this night differ from all others?).

Afterwards we started a discussion as to why so much pain and torture comes to the nation which gave to humanity so much. And if not recompensed, why the punishment?

The scanty meal came to an end and we began the second part of the Hagadah.

When the partners said “Leshana habaah Bejerushalajim” (Next year in Jerusalem) tears stood in the eyes of all present in the small hut. There was hope and gladness in their faces.

We hoped the future would indemnify us for what we have suffered. In this frame of mind, we closed the peculiar Seder evening.

I am sure this evening will remain in remembrance to all the participants, like other occurrences in the camp.

The Cherry Tree

Mottel Menczer

Mendele always dreamed of the big cherry tree that stood in front of his house in his old home in a small Bessarabian town. He was a little boy when he and his whole family were driven out. At that time, the blossoms of the cherry tree were white. Every spare moment, he would climb in to the tree and absorb into himself the sweetness of Beautiful Nature. In the Bershad camp, where we were together with his father and mother and three brothers, when we were reminiscing about our old home, Mendele would slowly come close and ask his father, “Is the tree still standing in front of our house and who is picking the cherries? Will I ever climb the tree again?” A sadness overcame all of us, hearing this child and his dreams. He went on to say, “Father, when I get home, my first deed will be to climb the Cherry Tree”. When the camp was liberated, and we slowly made our way home, we had to go to the place where Mendele’s parents had lived. They had arrived at their home several days before. When Mendele saw us, the first thing he did was to take us to his cherry tree. He climbed up agilely- and called out in a happy voice, “This summer, I myself will pick my cherries”. Tears welled up in our eyes, seeing the happiness of the child. The dream – the dream of a Jewish child materialized.

Bucharest

Introduction by Micha Menczer

After making their way back to Storozhynets and finding the town was a pile of rubble, my parents went on to Bucharest. The region between Storozhynets and Bucharest was still very unsettled with the Russians expanding their control over Romania so it was a dangerous journey. My mother’s two brothers, Eli and Coca, were both engineers living in Bucharest. During my parents’ internment in Bershad the brothers helped as much as they could by organizing food and clothing to be smuggled in. They continued to be a major support for my parents in Bucharest.

After leaving Bershad in 1944, Laura and Nelly had gone to Chernivtsi and remained there with another of my mother’s brothers, Leo, who had also miraculously avoided deportation. Another brother David and his family had been living in Bukovina before the war and were deported to Mogilev camp. After the liberation of Mogilev, they too made their way to Bucharest. By 1946 my parents, Laura and Nelly and my mother’s brothers and their families who were still in Europe were all in Bucharest.

Life in Bucharest was not easy. There were food shortages, health and sanitary dangers, extreme housing shortages with refugees flooding back and increased restrictions as the Soviet regime took over. Nelly described their housing as “a room in a crowded house, without a kitchen or refrigerator, just a hot plate, and scarce basic foods.” Nevertheless, after the horrific conditions in Bershad and life-threatening travels on leaving Bershad, it would have been a relief to be in Bucharest and be together again. Families helped each other with clothing, the basics of life and emotional support. Nelly was able to get tutorials to finish high school and my parents were able to find work. Life was restarting.

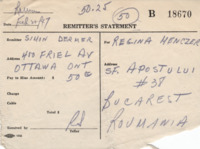

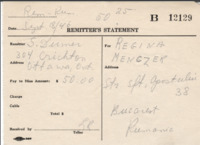

Help also came from family overseas. For example, there are receipts for $50 sent in 1946 by my mother’s brothers Simon and Sydney who had emigrated to Canada in the 1920s. Seeing my parent’s address, “Str. Sft. Apostului 38, Bucharest” on these receipts is powerful as it represents a real place and makes me wonder if this house is still there. Financial support also came regularly from my father’s family in Switzerland.

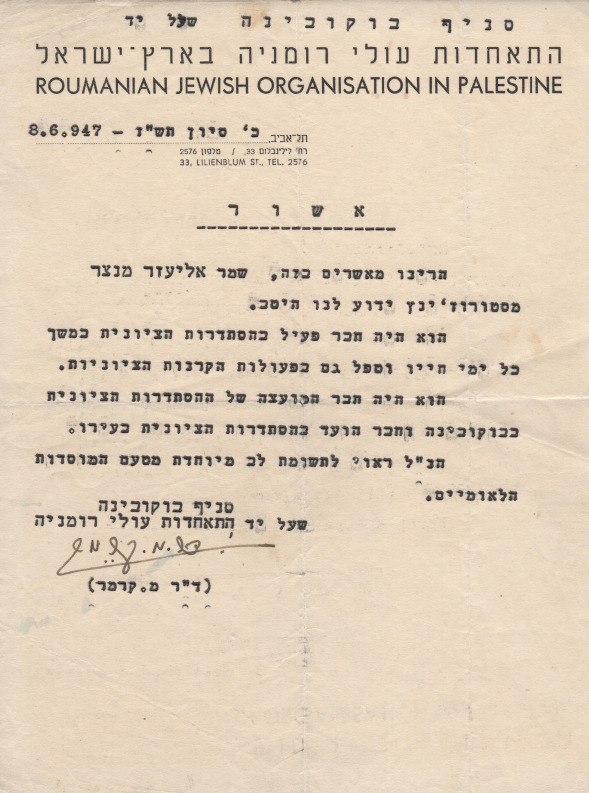

Nelly told me that in addition to efforts at basic survival and recovering some degree of health, much of the time in Bucharest was directed at getting “papers.” Initially there was a need to create identification papers, but as time went on my parents looked towards starting a new life in another country and the focus shifted to documents for emigration. I can’t imagine the enormity of these tasks for my parents who had come from three years of food scarcity, cruel detention, witnessing of innumerable murders, their own sickness, loss of family and perilous journeys back to Storozhynetz and then Bucharest. Even in these circumstances my father continued his activism in Bucharest supporting labour Zionism to create a homeland for Jews as the 1947 letter from the Romanian Jewish Organization in Palestine demonstrates. Their courage and will to survive inspires me.

I have not found any stories written by my father about the time in Bucharest. Whether they have been lost I don’t know. Perhaps none were written. There are letters from my parents to family in Canada, which I hope to get translated, that may give me more information.

The photos of the Dermer family, my mother’s family, in Bucharest in 1948 are particularly poignant as they represent the closing of a chapter in the family history in Bukovina and Romania. Soon after these photos were taken, my mother and father’s families scattered around the world to the United States, Canada, Israel, Argentina, Uruguay, Venezuela, Switzerland, Australia and perhaps elsewhere. No one from either family remains in Eastern Europe. I often wonder what our family’s lives would have been like if there had been no Shoah. Would we have stayed or emigrated? Would I have had siblings? What would it have been like to know my grandparents? These of course are unanswerable questions made even more stark by the reality that likely nothing remains in Bukovina that marks their long history except a few well-worn gravestones.

Translation of Letter from Roumanian Jewish Organization of Palestine

June 8, 1947

Tel Aviv 20th of Sivan תש"ז

June 8, 1947

(Certificate of) APPROVAL

We hereby acknowledge that Mr. Eliezer Menczer from “Storozhintz”(?) is well known by us.

He was an active member of the Zionist Union (The Jewish Agency) all of his life and also dealt with the activities of the Zionist Foundations (JNF etc.)

He was a member of the governing body of the Zionist Union (The Jewish Agency) in Bukovina as well as a member of his local branch.

The aforementioned person is deserving of special attention from the national agencies.

The Bukovina Branch, which is next to the Union of Roumanian Immigrants

Signed by Dr. M. Kramer

Emigrating to Canada

Introduction by Micha Menczer

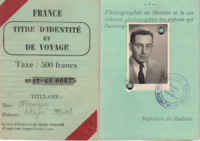

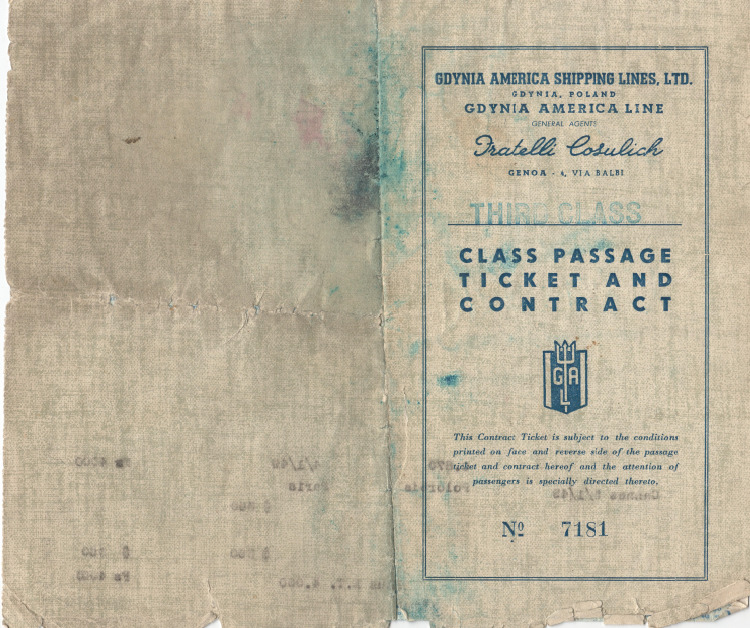

My parents left Romania in May 1948 holding Romanian passports. I don’t know the story behind these passports and exit visas, although I am sure they were the result of days and months of effort and countless interviews with the police and Romanian bureaucracy. Departures from Romania were not easy.

The passports themselves contain mysteries. For example, they show visas to Paraguay dated April 1, 1948. I had never heard of this until I looked at the passports years after their deaths. These visas were never acted on, and instead my parents, as evidenced by other stamps in the passports, landed in Marseille on May 20, 1948, and remained in France until January 7, 1949, when they emigrated to Canada.

Were the visas simply a mechanism to get out of Romania as Paraguay was taking in Jewish refugees or was there a serious intent to go to South America? One brother was in Argentina and a second emigrated to Uruguay in the late 1940s, so South America was a possibility. How our lives could have been different had the visas to Paraguay been used. I never had the opportunity to ask my parents these questions.

Their route to Canada was not direct. The ship leaving Romania had many survivors of the Shoah who were emigrating to Israel and it made a stop in Haifa for a day before proceeding to ports in Europe. My father’s brother Simon and sister Esther had emigrated to Israel in the 1930s and his niece Dora and nephews Arye and Chaim (children of his sister Pearl and her husband Moshe Speigel who were murdered by the Nazis in Vienna) were also in Israel. My mother’s brother David and his adult children (survivors of Mogilev camp) were headed to Israel too. Add to this the fact my father was a labour Zionist supporting the creation of a new state of Israel, the obvious question is why didn’t my parents join them?

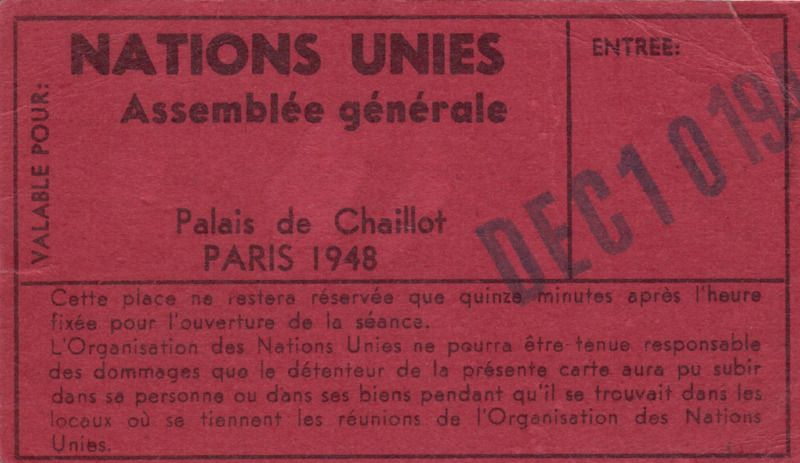

History provides part of the answer. On November 29, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that would divide the former British Mandate in Palestine into Jewish and Arab states in May 1948. Hostilities broke out almost immediately. After Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948, there was a full-scale attack on Israel by Arab countries and fighting continued until February 1949 when an armistice was reached.

At the time my parent’s ship docked in Haifa, the war was fully on. Without specific visas to Israel my parents could not step off the ship. My father’s family came to visit them on the ship, but he could not leave. My father wanted to “jump ship” and stay in Israel, but my mother insisted they were just coming from a harsh war and concentration camp and had barely recovered. She felt they needed a period of calm in Canada where her brothers lived. Her arguments prevailed and they proceeded to France and then Canada. I can only assume that my father intended to return to Israel one day. Sadly, he got seriously ill after a few years in Canada, passing away in 1959 never having a chance to step foot in Israel, a country he so passionately believed in, nor to see his family there again. Another large unanswerable question: what would our lives have been like had they “jumped ship” and stayed in Israel?

My parent’s ship sailed on, landing in Marseille on May 20, 1948. They made their way to Paris and took up residence in the Hotel Mirabeau, 10 Av. Emile Zola. Even though it was basic accommodation, my mother spoke of their time in Paris as a rebirth. Freedom from the camps and from increasing Russian control and restrictions in Romania were a healing balm for them. They did not have money and were supported by their extended families in Switzerland and Canada.

My father never lost his interest in politics and world events. Among his papers I found an admission ticket to the UN General Assembly in Paris dated December 10, 1948. How he got that ticket must be a fascinating story. On that day at the Palais De Chaillot, the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. For myself as a lawyer working on Indigenous rights, this is a fundamental international legal instrument. It sends chills down my spine to imagine my father, a Holocaust survivor, at the UN General Assembly the day they adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. How I wish I could talk to him about that day.

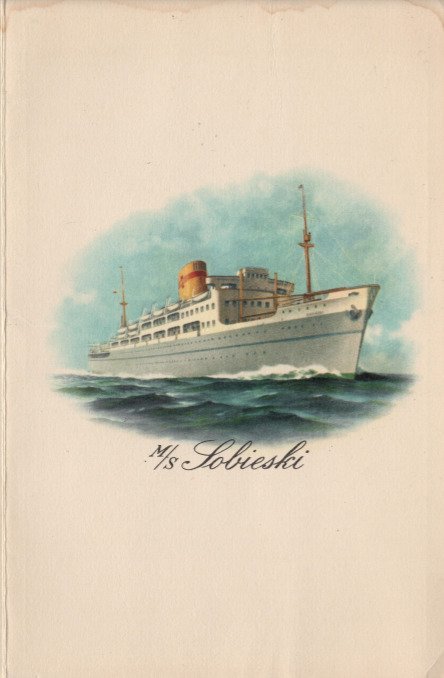

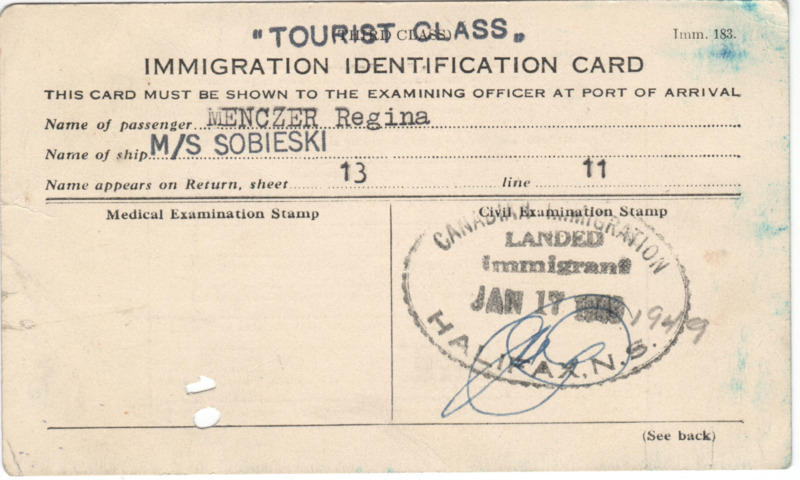

A few weeks later my parents left France on the MS Sobieski headed for Canada. They landed in Halifax on January 17, 1949. Life in Canada had begun.

Canada

Introduction by Micha Menczer

January 17, 1949, is an historic date in my parent’s lives. It is when they set foot in Halifax after years of turmoil, suffering and supreme tests of their will to survive. They took the train to Ottawa where my mother’s two brothers lived and moved into a small apartment at 317 Murray Street. Her brothers Sydney and Simon Dermer operated a family clothing store, Magasin Michel on Eddy St. in Hull, Quebec, a neighbouring city to Ottawa. My mother was fluent in French and began working as a bookkeeper and salesperson a few weeks after her arrival and continued there for twenty years. Later, a second store, Dermer Clothing, was opened on Wellington St. in Ottawa and my parents managed that business until the discovery of my father’s brain tumor and surgery in April 1954 prevented him from continuing. The photo of my father in front of the Ottawa store is important to me as it reveals the brief “normalcy” of my father’s working life in Canada and what could have been had he not developed serious health problems.

Twenty-two months after arriving in Canada and just as they were beginning to get a feel for this new country, I was born. This was a great surprise to my parents, my mother being 43 and my father almost 50. My mother believed that the malnutrition and hardship of the years in Bershad had brought on early menopause and that feeling unwell in the spring of 1950 was merely the flu. I can only imagine their shock and joy when the doctor told her that rather than the flu she was pregnant. Creation of new life in a new country must have been the ultimate statement of renewal for them. The reality of a newborn so soon after arriving must have been a great challenge but one they embraced with supreme joy. The numerous photos of “baby Micha” attest to this. These years were among the happiest in my parent’s lives.

Family life was central to my parents. My father spent a lot of time with me, particularly as he was recovering from the brain surgery in 1954 and afterwards as he gradually returned to work. I went to public school, however, my father also taught me extensively at home so I did not attend Hebrew school like other Jewish children. Some of my fondest memories are of him reading me Tales of Robin Hood and also the books his brother had sent from Israel for me.

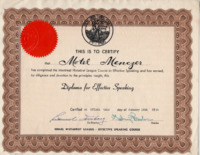

My father’s work in business was not, and had never been, the driving force for him. He was a lifelong student. He was anxious to learn about his new country. Soon after arriving, my mother and father took English and Citizenship courses at the venerable High School of Commerce in Ottawa. My father did not stop his learning there and took more courses such as the one shown on the 1954 “Diploma for Effective Speaking” to allow him to express his ideas better in his new language. As soon as they were able, my parents obtained their Canadian Citizenship. For them and many other immigrants to Canada this must have been an emotional moment after harrowing years in war-torn Europe.

My father’s activism in labour Zionism matters also continued. He was not hesitant to express concern when he felt his life-long principles in this cause may not have been reflected by Canadian organizations. The February 8, 1950, letter from the Zionist Organization of Canada is in response to a letter my father wrote raising concerns about their activities. I don’t have a copy of his letter to them, so I remain intrigued. It does reveal to me however that my father never lost his passion for labour Zionism and was not afraid, even as a new immigrant, to challenge established organizations.

My father’s stories remain the most powerful expression of his voice. I don’t know whether the stories were written before or after he came to Canada. Only one story is set in Canada and was obviously written here. “The Little Swastika” tells of a shocking experience when my parents were out for a walk on a spring day in this new country. This story remains a warning some 70 years later that hateful sentiments, not only against Jews but any persons seen as “the other,” present a danger to all.

My favourite photo of my father is of him in free and liberal Canada beside a sign declaring entry is allowed for “Christian Clientele Only.” His choice for this photo tells me a lot about his continued passion for social justice.

Sadly, my father’s brain tumor returned 1958 and could not be successfully treated. He passed away on December 23, 1959, at age 58 when I was 9. My mother, an exceptional woman in her own right, somehow found the strength to continue. She worked tirelessly at her job and at home and despite limited resources I lacked nothing. She raised me with love, guidance and support continuing what had begun with my father to shape the person I have become. My mother was able to see me finish my studies, become a lawyer and do meaningful, socially conscious work. I believe this gave her a great deal of satisfaction. She died in Ottawa March 18, 1982, at the age of 75.

The Little Swastika

Mottel Menczer

It was on the 7th of May, the day that the world murder (sic) ended and the democratic world carried off such a beautiful, hard-earned victory over fascism which had as its goal the enslavement of free nations (peoples-Volk in the plural) and of free will. I ventured forth with my wife for a walk in a quiet area of the city, and our eyes were delighted to see beautifully tended lawns, and we thought how good it was that this continent was so distant from the arena of war and that its inhabitants could enjoy peace and domesticity. We stopped in front of a green mailbox, and involuntarily, my eyes discovered on it a small swastika. One could see that the man who had etched this sign of murder knew something of symmetry. In a flash, my peace (of mind) vanished. Never again did I rejoice at a beautiful day in May, no longer did I admire the pretty houses and lawns. A single thought was drilled into my brain (The German is active-like a jackhammer, my brain drilled a single thought.) Five years after the war, who had etched this swastika there. It must have been not long ago because the green mailboxes are a new installation. Who wants to bring the flag of hatred and murder to this peaceful land?

My friend recently told me of being in the company of some people talking about German books, and one man said “I also have German books,” I have Hitler’s Mein Kampf which I rescued from Europe. A connection between the little swastika and Hitler’s Mein Kampf presses forward.

I had thought that after all the misery of four years in a concentration camp, in this beautiful land, I would forget everything that I suffered but here I discovered the unfortunate (also means lamentable or even disastrous) sign which pursues me on all my paths and awakens in me the terror of the re-awakening of fascism.

Ottawa, May 1950

My Parent's Legacy

Introduction by Micha Menczer

My father died more than 60 years ago but his legacy lives on through his writing of experiences during the Shoah. While “My Father’s Stories” are the foundation of this history, my mother’s brave role in their survival, her resilience and the rebuilding of life in Canada is equally important. They were partners every step of the way in life. My mother’s oral history of those times forms an integral part of my knowledge of their experiences. My mother, left a widow with a young child in 1959, taught me in words and by example the values of openness, generosity, respect for all people and a commitment to social justice.

My father’s legacy lives on also through the richness of his Yiddish stories. They describe in the most personal and fearless manner events that are beyond the imagination. It is essential to understand the Shoah and its impact on an individual level and not be overwhelmed by the statistics of deaths. His stories accomplish this.

My father’s stories have been read in schools, Holocaust commemorations in many cities and published in newspapers and magazines. The “Seder in the Loam Hut” story is a staple at our family Seders and in other households. It inspired the beautiful “Seder in the Himalayas” story written by Sandy Wheller in 1987.

For me assembling and sharing these stories, documents, photos has been a profound experience. It is a way to honour my father and mother and ensure that their history and courage is seen and understood. It also is a way for me to know my father better. He died when I was very young and while I have memories, they are through the lens of a child. I have many questions that I would like to ask him and so much I would like to tell him. That is not possible so the exploration of my parent’s lives through these materials is the closest I can come.

Telling the story of the Shoah so that it is real and understandable is essential. The history of my parents is the story of a family that suffered terribly but also survived and rebuilt their lives. I hope my father’s stories and the family history demonstrate that and enhance understanding of those times

Seder in the Himalayas

By Sandra Wheller

Since our return from Nepal I’ve wanted to write a story about an unusual Passover we celebrated. Finally, something special motivated me to write. My partner, Micha, is Jewish. His parents, born in Europe, survived the Holocaust but have since died; I was lucky enough, however, to find some writings by Micha’s father, Mottel Menczer, about his experiences from 1941 to 1944.

I knew of these writings, but I had never come across this particular one before. My curiosity grew as I held the yellowed newsprint, brittle with age, in my hands. The title read: Seder In the Loam Hut. A pencilled-in date of 1957 tells when it was published. I later learned that Mottel initially wrote his story in Yiddish and years later translated it into English.

I felt humbled after reading the article. The hardships they endured made me feel like our Seder was no match, which indeed it wasn’t — yet it seemed to me the two Seders had a special connection. Let me share a portion of Mottel’s story with you to begin. He sets the dreary scene describing survivors in the Ukraine in 1944 walking slowly towards their former homes. Tired, weary, their clothing shabby and torn after spending the last four years in a camp.

It was the day before Pesach and they were striving to reach the next village before dark to begin the holidays. He continues:

“we decided to make a festive Seder evening in spite

of all the mangle and peculiar circumstances ...

we were short of most ingredients, present even in

the poorest of Jewish homes. Hastily an article of

clothing was exchanged for a few potatoes and some

sour pickles, which was to be our feast ... When

the partners said L’shanal Ha-Baah B’yerushalayim!

tears stood in their eyes ... but there was hope and

gladness in their faces. We hoped that the future

would indemnify us for what we have suffered. In

this frame of mind we closed the peculiar Seder

evening.”

You can imagine how I felt about our ‘unusual’ Seder after reading of Mottel’s.

I wonder what he would think if he were here to listen.

We had been in Nepal several weeks and now, like most travellers, were hiking through small villages in the Himalayas. Our route followed that of the traditional traders and included a day’s rest in the village of Tatopani. We knew Passover began in the next few days but the exact date was not known to us as time appears to stand still when one is away from home for a long period of time. We met two Israelis at dinner who told us that the next day was Erev Pesach and they invited us to join them for some kind of Seder. The idea of having a Seder came together slowly as we wondered where to gather and what to eat. It started out as a gathering of eight to ten people at the most. Once we got started a momentum began that grew with excitement and anticipation. We asked our guesthouse family if we could have a special dinner explaining that it was sort of like a puja — a Buddhist religious ceremony. Before we had done anything else after discussing the food, a big pot of soup sat simmering on their stove. We went looking for apples to make a simple apple crisp for a dessert. With blossoms on the trees we felt lucky to find any at all. Before going to Nepal I never knew apples grew there!

Matzoh was the next challenge. Noga, our new found Israeli friend altered the Asian style bread, chapatti, making it thinner and dry. Watching the creation transform from dough rolled out flat with a tiny Asian rolling pin to the end product of 42 round matzot crackers was fascinating as it took place in a Nepali kitchen and the whole family was involved in the process. I felt privileged as an onlooker. Almost without realizing it the menu took on a traditional style as we had boiled potatoes, eggs, parsley, salty water and wine. We thought ginger root could replace maror as the bitter herb, instead of horseradish. We arranged swiss chard greens on a big silver tali plate and cut the boiled eggs placing them on top. The contrast of dark green and bright yellow was beautiful.

During this preparation time a fellow traveller passed by looking for us as she had intentions of a Seder too. We welcomed her and immediately she was involved. I reviewed what we were having and she asked: “What about the Haroset?” We had forgotten it! So off she went looking for walnuts. Soon Marlene was back with her prize of unshelled walnuts and we had the apples chopped and waiting. Some cinnamon and wine completed the delicious mixture and we filled a lovely clay bowl with it.

Just before dusk everything took on a festive look as we put the final touches on the tables. An extra cup was placed for Elijah and we hoped he liked Nepali home made wine. Micha went to hide the Afikomen wrapped in a silk scarf. The prize would be an extra serving of cheese to top the soup. This is a rare commodity in Asia and the longer you’re away from home the more precious it becomes.

Everyone began arriving. They all voiced their surprise at the sight of the ceremonial table with this huge, round wicker platter of matzah. Before we knew it there were twenty of us from three countries (Israel, the United States and Canada) who had somehow met in this small village to have a Seder. It seemed to be understood why we had come together this evening, so we concentrated on trying to piece the ceremony together without a Haggadah. “What goes next?” was the most asked question rather than: “What makes this night different than all other nights of the year?” Most of us knew when to eat the symbolic good and what the significance was. The Israelis sang some traditional folk songs along with the Seder songs. When it came to the Ten Plagues, the words: boils and hail took some time to describe and translate into English. Some improvising inspired us all. The Himalayan background stood silently as a nearly full moon rose high in the dark blue sky. The entire evening seemed magical as we sat in the middle of a garden in Nepal. When the Seder closed with everyone saying L’shanal Ha-Baah B’yerushalayim – next year in Jerusalem – we all were not sure we would meet as symbolically promised but our eyes were full of hope and gladness. The tears Mottel described in the eyes of his friends were not present any longer.

Perhaps this is part of the reward Mottel wished for when he wrote of past sufferings. I know he would be proud to see his son and other people’s children freely gathering for a Seder.

A Nepali greeting meaning ‘peace be with you’ expresses the spirit of sharing with others. “NAMASTE” to the second generation who honour their traditions even in the mountains of Nepal.

Respectfully dedicated to Mottel and Regina Menczer

Shalom,

Sandy Wheller

Closing Thoughts

Micha Menczer

Hate and aggression directed at “the other” was not limited to Jews in the Shoah and did not disappear after the Shoah. It continues today against many peoples. Perhaps my father’s stories can encourage more telling of the human experience. My parents taught me that it is necessary to recognize marginalization or attacks on others because of their race, religion or other difference. We need to be aware of the vulnerability of other peoples and also take action to protect them. This is the truest way to honour those who survived the Shoah and the blessed memory of those that did not.

I am in awe of my parent’s capacity to survive and not carry bitterness, but rather teach and demonstrate respect, love and kindness to all. They inspire me in my personal life and in my work. Today I am active in the Victoria Shoah Project in honouring those who died in the Shoah and those who survived through respectful public commemoration and by fighting racism and hate.

As the late Eli Weisel stated in his 1986 Noble Peace prize acceptance speech:

“I swore never to be silent whenever and wherever human beings endure suffering and humiliation. We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented.”

In closing, I dedicate this to my parents, Mottel and Regina Menczer.

They gave me everything.

PLEDGE OF MUTUAL RESPECT AND SUPPORT

Silence in the face of injustice is to agree with the ones who perpetrate injustices.

Never will we stand by to allow expressions of racism, xenophobia or discrimination against any peoples in our community.

We will do our utmost to encourage meaningful dialogue and positive action to foster understanding among diverse groups based on mutual respect.

Thoughts on the Exhibit

Micha Menczer

I appreciate the opportunity that Professor Helga Thorson has given me to participate in “Stories of the Holocaust: Local Memory and Transmission.” I especially thank student Linnet Chappelka for her hard work in preparing this segment of the exhibit.

Linnet Chappelka

Working with Micha on this project to document the lives and legacy of his parents has been remarkable. From the onset, it has been our goal to remember and commemorate the lives of Mottel and Regina. So often in Holocaust studies, the focus is on the large scale-events such as deportations and liberations. It has been my intent to bring attention to the public history of the Holocaust and the individual lives affected. Getting to know Mottel and Regina through the stories and photos and has been an honour, and I am so proud to be able to contribute to the digitization of their lives and making this exhibit accessible to the public. Thank you to Micha for allowing me to share his parent’s story.

Micha Menczer is the senior partner of Arbutus Law Group LLP based in Victoria. He has been a lawyer since 1975 working on Indigenous and Aboriginal rights his entire career. He has acted as legal counsel on several Aboriginal law cases before the Supreme Court of Canada as well as being the lawyer for the successful negotiation and implementation of a historic self-government agreement for a First Nation in British Columbia. Internationally, Micha has worked with indigenous peoples in Central America and Vietnam.

His work has been recognized by his peers, who voted to include him in the publications Best Lawyers in Canada and the Canadian Legal Expert Directory as a leading practitioner in the area of Aboriginal Law.

Micha has been active in Holocaust (Shoah) commemoration and education in Ottawa, Vancouver and Victoria and is a founding member of the Victoria Shoah Project.

Linnet Chappelka is a 4th year student at the University of Victoria, where she is completing her degrees in Germanic Studies and Art History and Visual Studies. In the fall of 2021 she will be attending the University of British Columbia to pursue Masters' degrees in Archival, Library, and Information Studies. She aims to make libraries and archives more accessible and inclusive to the public. Linnet has contributed to this exhibit as a volunteer with Dr. Helga Thorson's GMST 410 X GMST 585 Special Topics: Holocaust and Memory Studies course. This experience has been remarkable, and Linnet is greatful to have learned so much about the Dermer and Menczer families, and for being able to share their lives and stories with the public.