Imitating Authority and Evading the Law: Pastiche in Judge Woolsey's Opinion

Introduction

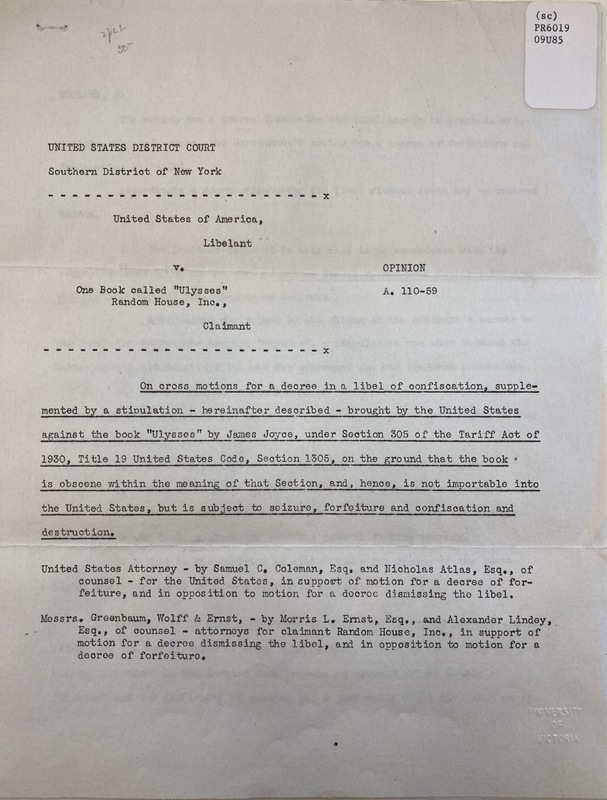

“United States of America, Libelant v. One Book Called “Ulysses”, Random House, Inc., Claimant., Opinion A. 110-59” is a legal opinion written by United States District Judge John M. Woolsey. It is dated December 6th, 1933, and holds the judgment that was delivered in the United States District Court, Southern District of New York, on December 15th, 1933. The United States of America is represented by attorneys Samuel C. Coleman and Nicholas Atlas. The claimant, One Book called “Ulysses” Random House, Inc., is represented by Morris L. Ernst and Alexander Lindey. Their firm, Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst, is located at 285 Madison Avenue, Borough of Manhattan, New York City. The intended audience is the United States District Court. The document, housed in the University of Victoria Library, Special Collections, is identified by the call number PR6019 09U85. The opinion is typewritten on eight pages of unbound paper. Judge Woolsey’s signature appears on page 8 in black ink.

This document provides insight into the history of Ulysses’s publication in the United States and how this history is related to law. Moreover, we are intrigued by how a literary work is treated and represented in the judicial system. The opinion is notable for its rhetorical style: instead of supporting his opinion with legal analysis, Woolsey employs poetic language to express his decision. Due to the opinion’s notoriety, Woolsey’s language raises questions of the effects of style in a legal setting. Considering that literary imitation and style are central thematic and formal features of Joyce’s work, his use of pastiche and parody will guide our reading of Woolsey’s opinion. Through this lens, we will explore how Woolsey’s approach influences the authority and reception of this legal document.

Literature Review

On December 6, 1933, United States District Judge John M. Woolsey submitted his opinion on the “United States of America, Libelant v. One Book Called ‘Ulysses’” case. This document asserts that James Joyce’s Ulysses is not “obscene within the legal definition of the word” (Woolsey 6) and was essential to the legalization of Ulysses’s publication in the United States (Ferguson 435; Gleeson 1011; Spoo 1027). The argument is multifaceted: Woolsey claims that the text is “not pornographic” (3) because Joyce’s ambitious, and strikingly realistic, representation of his characters’ minds “required him incidentally” (5) to use profane language, but he did so in a manner that does not “excite the sexual impulses” of the “normal person” (8). Thus, Woolsey proclaims that Ulysses should be permitted to enter the United States (8).

This interpretation of obscenity law, which permits profanity and sexual content when it occurs in a “sincere and honest” (Woolsey 5) manner, helped reshape the legal landscape and consequently has been the subject of significant scholarship. Specifically, Woolsey’s writing style has received notable attention. For example, Robert Spoo asserts that the opinion is “equal parts legal ruling and literary analysis” (1027). More pointedly, Kevin Birmingham describes the document as a “rave review” of Ulysses (992). These legal critics, among others, observe how Woolsey employs minimal legal analysis and instead expresses his opinion through “literary flourishes” (Gleeson 1019). Additionally, biographical information about the judge suggests that his mode of writing is congruent with his personal interests. For example, John Gleeson notes that Woolsey had an interest in literature (1016) and Robert Ferguson comments that Woolsey was “well-educated, extremely well-read, well-known in literary circles, and well up on his own collection in first editions of rare books” (441). Evidently, Woolsey was familiar with literature and its politics when he was appointed to judge the Ulysses case. Consistent with these observations, there is a critical consensus that Woolsey channels literary rhetoric rather than legal.

Woolsey’s approach has received mixed support from legal scholars. Spoo perceives the opinion as a “flexible, creative response to social and legal realities that constrained judicial approaches in the 1930s” (1028). Specifically, the judge’s creativity is rooted in his choice of “eloquent and forceful” language (Birmingham 992). Moreover, the outcome of Woolsey’s opinion is universally considered a positive one: it helped bring Joyce’s text to the United States and the legal system step towards changing outdated obscenity laws (Feguson 435-436; Gleeson 1011, 1020; Spoo 1027). Conversely, Gleeson highlights the flaws of this technique: Woolsey’s rich language is a substitute of the “work he was supposed to be doing” and “conflates whether a book should be available for reading and whether it is a good read” (1020). This form of judging, in which the law recedes to the background, is described as “defective” (Ferguson 436; Gleeson 1020). Similarly, Ferguson condemns the language of the opinion because “it allows Woolsey to obscure his difficulty with extant law” (444). In other words, Woolsey masks the lack of legal analysis within his vibrant language.

Despite the widespread recognition of literary qualities in Woolsey’s opinion, few critics have attended to these features. Ferguson, for instance, briefly notes the tone and narrative point of view of Woolsey’s writing. He argues that Woolsey’s condescending tone portrays him as both a legal and literary authority: he is “the expert critic” (447) and “a remarkably conscientious, objective, and cultured judge” (450). Additionally, the fluctuation in narrative perspective creates a “seemingly objective narrator” (450). Therefore, Ferguson concludes that Woolsey’s writing style gives the impression that his decision is undoubted and uncontroversial (450). Interestingly, Gleeson forges a connection between Woolsey and John Quinn, a prominent modernist figure (Zilczer 57), in suggesting that both men fall victim to the same “syndrome”: they overwrite their prose with the aim of “showing that [they are] capable of playing with language” (Gleeson 1019). The result is an imitation of literary rhetoric (1020). Additionally, although scholars have mentioned Woolsey’s affinity for literature, critics have yet to explore how it informs the literary qualities of his opinion. In light of these observations, there is reason to read Woolsey’s rhetoric through a literary lens.

This technique of literary imitation, namely pastiche, is an essential feature of Ulysses itself (Hutcheon, A Theory of Parody 38, Gilbert 290, Lawrence 124-126). Linda Hutcheon defines pastiche as a genuine imitation of literary style without a single source text; it does not intend to mock or critique, but rather replicates a style of writing (A Theory of Parody 38). This definition provides scholars with a basis for examining instances of pastiche in Ulysses. Most frequently, the rapidly shifting styles of “Oxen of the Sun” have been interpreted as genuine imitation: “that willful exaggeration of mannerisms which points a parody is absent and the effect is rather of pastiche” (Gilbert 290). Kathleen Wales contributes to this interpretation by demonstrating that Joyce rarely interacts directly with source texts in this episode (392). These observations, that this episode lacks the “satiric intention” (Gilbert 290) and “parallel” (Wales 329) texts of parody, is reflected in Hutcheon’s remark that Joyce’s “stylistic imitations” in “Oxen of the Sun” are examples of pastiche (A Theory of Parody 38). Karen Lawrence also explores the presence and effect of pastiche in The Odyssey of Style in Ulysses. She agrees with the assertion that Joyce’s technique in “Oxen of the Sun” does not undermine or exaggerate the literary models he imitates, but instead pays homage to their stylistic “system” (124-125; 137). The specific styles Joyce emulates in this episode are often “forms in which the writer seeks to persuade” (126); the models are essays, sermons, cultural criticism, and philosophy (126). Consequently, Joyce’s pastiches derive authority from the literary modes they replicate (126). Interestingly, Woolsey’s literary imitation is similarly intended to be authoritative and persuasive in a legal setting.

Unlike pastiche, Hutcheon defines parody: “as a form of ironic representation…it both legitimizes and subverts that which it parodies” (The Politics of Postmodernism 97). Critics have noticed a similar distinction between pastiche and parody in Ulysses. One predominant critical conversation of Ulysses explores parodies of rhetoric (Lawrence, Wiendenfeld). Consistent with Hutcheon’s definition, Lawrence interprets Joyce's parodies of contemporary discourses in “Cyclops”—such as journalistic, legal, scientific, and religious—as evidence of the dual nature of parody: although “the dead styles cannot be resuscitated, Joyce revitalizes old forms” (108). Barbara Leckie demonstrates parody’s duality by illustrating how Joyce’s parody of sensationalist novels in “Nausicaa” simultaneously problematizes and perpetuates literary regulation (65). Censorship, as it appears in this episode, critiques the publication history of Ulysses itself by provoking censors with sexually suggestive scenes while also self-censoring by shrouding explicit content in sensationalist language (65). Likewise, Logan Wiendenfeld reads “Aeolus” as an imitation and critique of classical rhetoric (65). While the episode’s intertextuality and “banal narrative” of men arguing about rhetoric parodies the structure and history of rhetorical treatises (66), the form of “Aeolus” parodies their content: the newspaper press prints “dead letters” that are devoid of meaning (71). Consequently, the layered parodies in “Aeolus” expose “the rhetoric of rhetorical treatises” (65). Each of these scholars support Hutcheon’s delineation of pastiche and parody.

There are intriguing similarities between Joyce’s use of pastiche and Woolsey’s imitation of literary style in his opinion. This interpretation of the opinion is an extension of criticism that notes Woolsey’s literary flair. Joyce’s most notable use of pastiche is found in “Oxen of the Sun”; his demonstration of pastiche’s key features and implications provides a lens for reading Woolsey’s opinion. Subsequently, the present paper aims to expand the limited analysis of Woolsey’s writing and will argue that the opinion can be interpreted as a pastiche, in the sense that it is a genuine imitation of a literary style—specifically due to Woolsey’s syntax, use of figurative language, and narrative tone— and that this reading nuances the current discussion of both the documents’ limitations and effectiveness.

Pastiche in "Oxen of the Sun"

Among the numerous pastiches of “Oxen of the Sun” is Joyce’s imitation of Romanticism. In this episode, Bloom is at Holles Street Maternity Hospital, in the company of various other characters, awaiting the birth of Mina Purefoy’s baby. When the Romantic pastiche begins, Bloom shifts his attention away from his surroundings and allows his mind to wander:

“The voices blend and fuse in clouded silence: silence that is the infinite of space: and swiftly, silently the soul is wafted over regions of cycles of generations that have lived. A region where grey twilight ever descends, never falls on wide sagegreen pasturefields, shedding her dusk, scattering a perennial dew of stars” (Joyce, lines 1078-1082).

Scholars have suggested that this is likely a pastiche of Romantic writer Thomas De Quincey (Gordon 350); however, Lawrence argues that even without this knowledge, the passage is identifiable as a pastiche due to its literary features (125-126). A distinct feature of Romanticism is the absence of realism; this is reflected in Joyce’s use of poetic and figurative language (Dabundo 3, 158-159; 434). For example, the opening lines of this passage are marked by prolific sibilance: the “s” sound echoes through “voices,” “fuse,” “silence,” “space,” and “swiftly, silently the soul” (Joyce 1078-1080). This sibilance slows the reader as each protracted “s” is read and draws attention to the images these lines evoke. Rather than explicitly expressing how Bloom stops focusing on the conversation around him, Joyce describes how the “voices blend and fuse” in Bloom’s ears and how his “soul is wafted” away from the present moment (1078; 1079). Another element of Romantic figurative language in this passage is the personification of nature (Varner 238). In Joyce’s text, “twilight” is depicted as “shedding her dusk, scattering a perennial dew of stars”; the actions of “shedding” and “scattering” humanize this feature of the natural world (1080-1082). Moreover, Romantic writers use nature as a mirror for human experience; “twilight” descending is a representation of Bloom’s consciousness entering a trance-like state of introspection (1080; Varner 238). Here, Joyce evades realism in favour of lyrical language and fanciful imagery.

Other diction in this short passage points towards another Romantic trope: the sublime. The Romantic sublime is generally defined as an intellectual-emotional experience that occurs when one perceives anything that evokes a sense of “obscurity, vastness, difficulty, infinity…[or] magnificence” (Milbank 228; Shaw 2, 126-127). This is often tied to personal transcendence: the sublime awareness of “infinity” and “magnificence” (Milbank 228) occurs when an individual transgresses the boundaries of introspection (Shaw 126). Joyce evokes a sense of the sublime through diction that emphasizes “vastness” (Milbank 228). For example, the silence Bloom sinks into is compared to the “infinite of space” and his soul is swept away to a “region where grey twilight ever descends”—a liminal region where twilight never takes hold but continues to fall forever (Joyce 1080-1081). As his “soul is wafted” into the limitless silence, Bloom reflects on elements of his life, including his close relationships: “is it she, Martha, thou lost one, Millicent, the young, the dear” (1101-1102). Later in the episode, Joyce confirms Bloom’s meditative state by explicitly explaining that he had been “staring hard” (1181) at a bottle on the table while “recollecting” (1189) his past. Thus, Bloom’s moment of reflection can be interpreted as an experience of sublime transcendence.

Each of these Romantic literary features indicate that this passage is a pastiche of Romanticism. Although Joyce is bound to the limits of this genre’s conventions, it is highly effective for illustrating this moment in “Oxen of the Sun.” Specifically, the form and content of the passage align extremely well: Romanticism’s departure from realism—marked by poetic language, whimsical imagery, personified nature, and the transcendental experience of the sublime—accurately captures Bloom’s free-flowing consciousness. Not only does this alignment emphasize that this passage is a pastiche but it also signals that it is not a parody. Parody, while a similar form of imitation, is distinguished from pastiche because it ultimately undermines the source it imitates (Hutcheon 97). In Ulysses, this satirical edge is rooted in an incompatibility between the form and content (Leckie 65; Weidenfeld 65-66); however, this is not present in “Oxen of the Sun.” Lawrence’s suggestion that Joyce derives authority from the styles he imitates is another facet of the pastiche’s effectiveness (126). Due to the accordance of the style and the plot, and the absence of satire, Romanticism appears to be the most applicable mode of expression for this passage. Concurrently, Joyce establishes his literary supremacy by effectively utilizing a high-cultural artistic technique. Therefore, the Romantic pastiche both demonstrates Joyce’s literary dexterity and enhances Romanticism’s stylistic conventions.

Pastiche in Woolsey's Opinion

In a similar manner, Woolsey emulates literary style. To assert that judging whether Ulysses violates obscenity law required him to determine Joyce’s intent by reading the novel, Woolsey writes:

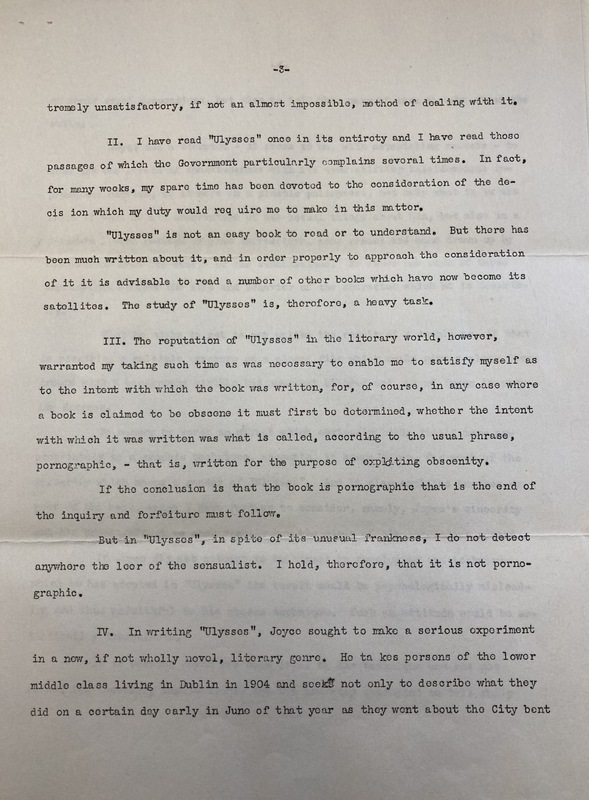

“The reputation of “Ulysses” in the literary world, however, warranted my taking such time as was necessary to enable me to satisfy myself as to the intent with which the book was written, for, of course, in any case where a book is claimed to be obscene it must first be determined, whether the intent with which it was written was what is called, according to the usual phrase, pornographic,—that is, written for the purpose of exploiting obscenity” (Woolsey 3).

The structure of Woolsey’s writing is inconsistent with concise legal rhetoric: he expresses simple ideas using complex and lengthy sentences. Commas, em dashes, and redundant phrases, such as “for, of course” and “according to the usual phrase,” connect ideas that would be more easily understood as separate sentences (3). These syntactic qualities embellish Woolsey’s writing and create a narrative flow that is identifiably literary and not legal. Nine months after Woolsey’s opinion was issued, the Circuit Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, upheld his decision in a second legal opinion on this case. This document, entitled “United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce (Random House, Inc., Claimant)” and written by Judge Augustus N. Hand, offers a compelling source of comparison to Woolsey’s opinion due to its use of legal style. For example, Hand’s syntax is simple and concise: “the question before us is whether such a book of artistic merit and scientific insight should be regarded as “obscene” within section 305(a) of the Tariff Act” (United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit). This statement expresses the overarching purpose of the trial in one uncomplicated sentence. Wooley’s assertion quoted previously performs the same function but does so in a sentence that is triple the length of Hand’s.

Woolsey’s departure from legal rhetoric is also evident in his use of figurative language. He employs similes to describe Joyce's prose: “each word of the book contributes like a bit of mosaic to the detail of the picture which Joyce is seeking to construct for his readers” (Woolsey 6). To describe how human consciousness is depicted in Ulysses, Woolsey compares the mind to “a plastic palimpsest” which reflects one’s “ever shifting kaleidoscopic impressions'' from “a penumbral zone residual of past impressions,” the present moment, and those which arise “from the domain of the subconscious” (4); simply put, Joyce successfully captures explicit and implicit cognitive experiences. Rhetorical embellishments also appear in the form of metaphors. For example, he equates reading suggestive passages of Ulysses to “a rather strong draught to ask some sensitive, though normal persons to take” (8). When successful, similes and metaphors perfectly capture the author’s meaning but call on the reader’s interpretative skills to do so. Therefore, Woolsey’s opinion requires literary decoding and is open to subjective analysis which is incompatible with legal modes of writing. In comparison, Hand conveys similar points without using figurative language. For example, to describe Joyce’s success in illustrating human cognition, Hand summarizes Ulysses as a “sincere portrayal with skillful artistry of the ‘streams of consciousness’ of its characters” (United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit). This prosaic statement contrasts Woolsey’s palimpsest simile (4). Likewise, Woolsey’s draught metaphor is juxtaposed with Hand’s literal claim that the text “justly may offend many” (United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit). Subsequently, Hand’s writing suggests that objectivity is a feature of legal style. Another instance of Woolsey flaunting his lyrical finesse is his use of pithy, memorable phrases. To articulate that, despite including explicit passages, Ulysses contains no unjustified content, he claims that the novel is unsullied by “dirt for dirt’s sake” (Woolsey 6). Similarly, to rationalize controversial scenes in Joyce’s novel, Woolsey declares: “his locale was Celtic and his season Spring” (5). These aphoristic sayings depict Woolsey as a highly quotable literary authority.

Lastly, Woolsey’s opinion is characterized by his distinct literary tone. For example, he uses ostentatious language to describe his role: it is the “inherent tendency of the trier of facts, however fair he may intend to be, to make his reagent too much subservient to his own idiosyncrasies” (7). Although he could have simply used the word “judge,” Woolsey characterizes himself as the “trier of facts,” and uses the phrase “subservient to his own idiosyncrasies” to emphasize the familiar idea that a reagent must be impartial to the judge’s beliefs (7). These extravagant phrases elevate the literary quality of his prose. Simultaneously, Woolsey uses diction such as “real,” “undoubtedly,” “true,” and “impossible” to suggest that his argument is unquestionably valid; consequently, his tone is both “eloquent and forceful” (Birmingham 992). Additionally, the tone is explicitly attributed to Woolsey himself through his use of first-person phrases such as “my considered opinion” and “it seems to me” (8, 6). As a result, the opinion’s grandiose, commanding tone infuses Woolsey himself with authority as he is inserted as the narrator-figure. The tone of Hand’s opinion is equally authoritative to Woolsey’s; however, its authority is derived from extensive analysis of legal precedent rather than Hand’s language itself. For instance, he cites “Halsey v. New York Society for Suppression of Vice, 234 N.Y. 1, 136 N.E. 219, 220” to argue that obscenity in Ulysses should be assessed within the context of the entire novel (United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit). Case analysis, such as this, is a fundamental component of legal rhetoric and almost entirely missing from Woolsey’s decision.

As Joyce's use of literary devices indicates a pastiche of Romanticism in “Oxen of the Sun,” Woolsey’s syntax, figurative language, and narrative tone invite a reading of the opinion as a pastiche of general literary style. Interpreting Woolsey’s opinion as a pastiche is further supported by its dissimilarities to Hand’s subsequent opinion on the matter which exemplifies typical legal writing style. This analysis of Woolsey’s opinion contributes to the critical conversation of his “literary flourishes” (Gleeson 1019). On one hand, the opinion has been praised for being creative, persuasive, and ultimately effective in reshaping the legal landscape (Birmingham 992; Spoo 1028). Conversely, scholars argue that Woolsey’s writing style masks his lack of legal analysis and, therefore, the opinion is legally “defective” (Ferguson 436). Subsequently, he has been criticized for his self-indulgent approach (Birmingham 998; Ferguson 447-450; Gleeson 1019). These incompatible observations can be reconciled by considering the implications of pastiche. Specifically, in Ulysses, pastiche allows Joyce to use literary forms that are consistent with the ideas he depicts, demonstrate high-cultural literary artistry, and infuse the text with authority. The opinion benefits from pastiche in a similar way and its effectiveness can be attributed to its status as a pastiche. For example, the narrative flow and interpretation, incited by figurative language, engages readers as if it were prose, rather than a legal document. Additionally, Woolsey’s artistry creates an authoritative tone and establishes him as a convincing literary figure. Consequently, the opinion has been praised as a literary achievement in its own right (Birmingham 992; Gleeson 1019; Spoo 1028). However, the legal limitations of the opinion can also be traced to the technique of pastiche. Joyce demonstrates that pastiche is successful when the content and prescribed conventions are in agreement. Woolsey’s style is unsuitable for conducting legal analysis; therefore, the pastiche restricts him to writing a literary review that, as critics have expressed, is a weak legal statute (Ferguson 435; Gleeson 1020). Thus, approaching Woolsey’s opinion with a literary lens provides a novel understanding of its strengths and limitations.

Works Cited

Birmingham, Kevin. “The Prestige of the Law: Revisiting Obscenity Law and Judge Woolsey’s Ulysses Decision.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 4, 2013, pp. 991-1009. https://doi.org/10.1353/jjq.2013.0066.

Dabundo, Laura. “Encyclopedia of Romanticism: Culture in Britain, 1780s–1830s.” Encyclopedia of Romanticism (Routledge Revivals), 1st ed., Routledge, 1992, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203092590.

Ferguson, Robert A. "Judicial Rhetoric and Ulysses in Government Hands." Rhetoric & Public Affairs, vol. 15 no. 3, 2012, p. 435-466. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/484409.

Gilbert, Stuart. James Joyce’s Ulysses: A Study. Faber & Faber, 1930.

Gleeson, John. “The Ulysses Cases and What They Reveal about Lawyers and the Law.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 4, 2013, pp. 1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1353/jjq.2013.0071.

Gordon, J. (1998). "Tracking the Oxen." Journal of Modern Literature, 22(2), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1353/jml.1999.0034.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Methuen, 1985.

Hutcheon, Linda. The Politics of Postmodernism. Taylor and Francis, 2003, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203426050.

Joyce, James. “Oxen of the Sun.” Ulysses. 1922, Vintage Classics-Penguin Random House, 2022, pp. 314-349.

Lawrence, Karen. “‘Cyclops,’ ‘Nausicaa,’ and ‘Oxen of the Sun’: Borrowed Styles.” The Odyssey of Style in Ulysses, Princeton University Press, 1981, pp. 101-145. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7ztfw8.

Leckie, Barbara. “Reading Bodies, Reading Nerves: ‘Nausicaa’ and the Discourse of Censorship.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 1/2, 1996, pp. 65–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25473788.

Milbank, Alison. “The Sublime.” The Handbook of the Gothic, edited by Marie Mulvey-Roberts, Palgrave Macmillan, 1998, pp. 226–232.

Shaw, Philip A. The Sublime. Second edition., Routledge, 2017, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315717067.

Spoo, Robert. “Judging Woolsey Judging Obscenity: Elitism, Aestheticism, and the Reasonable Libido in the Ulysses Customs Case.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 50, no. 4, 2013, pp. 1027–1049., https://doi.org/10.1353/jjq.2013.0076.

United States, Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce (Random House Inc., Claimant).72 F.2d 705, 7 Aug 1934. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/72/705/1549734/

Varner, Paul. Historical Dictionary of Romanticism in Literature. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvic/detail.action?docID=1865504.

Wales, Kathleen. “The ‘Oxen of the Sun’ in ‘Ulysses’: Joyce and Anglo-Saxon.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, 1989, pp. 319–32. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25484960.

Wiendenfeld, Logan. “The Other Ancient Quarrel: “Ulysses” and Classical Rhetoric.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 51, no. 1, 2013, pp. 63-79. https://doi:10.1353/jjq.2013.0102.

Woolsey, John M. United States of America, Libelant v. One Book Called “Ulysses”, Random House, Inc., Claimant., Opinion A. 110-59. 06 December 1933. PR6019 09U85. Special Collections, University of Victoria Library.

Zilczer, Judith. “John Quinn and Modern Art Collectors in America, 1913-1924.” The American Art Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, 1982, pp. 56-71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1594296.