Ramsay Sarah-Grace (Little Magazines)

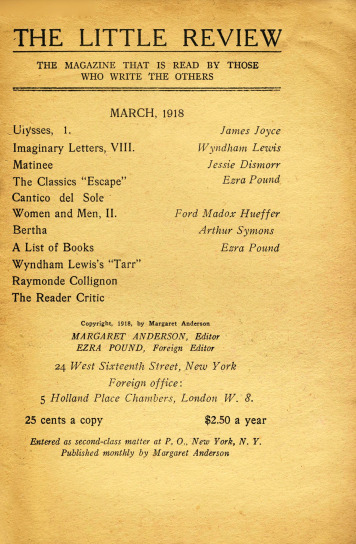

The object I selected is The Little Review, vol. 4, no.11 which was published in March 1918. This edition was published by Margaret Anderson and edited by Anderson and Ezra Pound. In it, there are writings by contemporary modernist authors, book recommendations by Pound, reader criticism of the magazine, and advertisements.

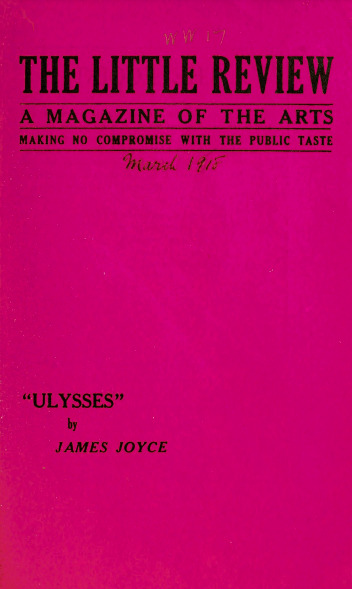

The magazine is 6 x 9”. It is a 64 page paperback with a bright pink cover. The cover is mostly plain except for the title of the magazine, the tagline “making no compromise with the public taste,” and, notably, the words “Ulysses by James Joyce.”

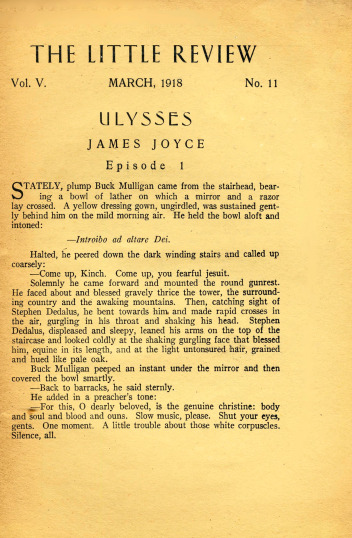

It begins with the first episode of Ulysses by James Joyce, as advertised on the cover. This is the first time any part of Ulysses was published.

Frankly, I picked this object because it is one of the coolest things I have ever seen. I was instantly drawn to this particular edition of the magazine because of the bright colour, but it turns out the bright colour is one of the least interesting things about it. The Little Review is a captivating time capsule of the modernist era. It is fascinating to see these great works written by renowned authors as they were originally published — complete with ads, notes from the editors, and reader criticism. The writers seem to take themselves seriously and pride themselves in creating great art, but there is also humour throughout. Although this edition of The Little Review was published more than one hundred years ago, the writing is relevant and exciting. It feels alive. This particular edition also caught my attention because it was the first time anyone (outside of Joyce’s personal connections, I suppose) could read a part of Ulysses. It is interesting to see the way Ulysses was presented to the world before Joyce even finished writing it.

I will use this edition of The Little Review to explore how Ulysses was initially marketed, to whom it was marketed, and how that contributed to the overall legend of Ulysses. When I began my research, I thought it would be interesting to examine the reader criticism section and the ads in The Little Review to see who the magazine is targeting. I was also interested in examining how the magazine specifically presents Ulysses to its audience. Because the name of Ulysses is published on the front cover of the magazine and there is a page of praise for James Joyce as a writer, it seemed reasonable to assume that Ulysses was sold to readers as a masterpiece from the beginning.

Although I began my research prior to finishing Ulysses, I had already observed that the text may have offered some insight into how Joyce wanted his novel to be received. I had noticed that there are moments in the novel — such as in “Scylla and Charybdis” when the characters are discussing the concept of an Irish Shakespeare — where Joyce seems to be alluding to himself as a Great Artist who can change the literary landscape of the time.

I planned to review literature that discusses the history of The Little Review, early marketing of Ulysses, and Joyce’s reputation as a writer prior to the release. I started my research by looking at Joyce Wexler’s “Who Paid for Marketing?” and Ira Nadel’s “Marketing Modernism.” When I began my research, I had no idea what I would discover or why any of this ultimately matters, but I was excited to learn more.

Literature Review

When The Little Review published the first episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the little magazine seemed to promote Ulysses as the most important work in that edition. There is much literature that discusses the role early marketing played in crafting Ulysses’s legacy. Some literature suggests that Ulysses was deliberately marketed to achieve mainstream success while other literature suggests that it was marketed as inaccessible and rebellious at the expense of mainstream success. Other literature suggests that pretentious marketing may have unintentionally caused mainstream success.

Joyce may have intentionally marketed Ulysses to achieve mainstream success. The chapter “Marketing Modernism” in Modernism’s Second Act: A Cultural Narrative by Iral Nadel — a book about the later stages of modernism — discusses the destruction of modernist innovation through commercialization (Nadel 91). Despite the eventual negative effects, Nadel suggests that commercialization began with early modernists, including Joyce in 1918, consciously creating readers in the way any advertiser creates consumers (Nadel 77). In Timothy Galow’s article “Literary Modernism in the Age of Celebrity” in Modernism/Modernity, Galow uses F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein as examples to demonstrate how modernists took advantage of the rising celebrity culture by intentionally creating their own public personae (Galow 315). Joyce was likely just as aware of the importance of marketing himself as a commodity.

Some other literature suggests that Ulysses was intentionally marketed as countercultural at the expense of mainstream acceptance. Joyce Wexler’s article “Who Paid for Modernism?” in The Sewanee Review examines the struggles modernists faced by refusing to compromise with publishers to make their works more marketable to readers (Wexler 444). The Little Review does, after all, pride itself in “making no compromise with the public taste.” Many modernists eventually sought patrons over commercial publishers (Wexler 446). Alan Golding’s article “The Dial, The Little Review, and the Dialogics of Modernism” in American Periodicals offers specific insight into The Little Review by comparing it to contemporary modernist little magazine The Dial. Golding argues that the two magazines complemented each other; The Dial targeted readers while The Little Review targeted artists (Golding 44). Ulysses was published in The Little Review demonstrating that the rebellion and avant-garde nature of the work was more important than mainstream appeal.

Other research suggests that the pretentious marketing of Ulysses as “high culture” significantly contributed to its success. The article “Popular Modernism: Little Magazines in the American Daily Press” in PMLA by Karen Leick focuses on the mainstream media buzz surrounding Joyce and other modernists. Leick examines how popular media outlets such as The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Life would regularly mock the inaccessibility of modernist little magazines (Leick 129). Because of this attention, Leick argues, many modernists became well-known by the general public even though most people had not read their works (Leick 136). Therefore, average people were already somewhat familiar with Joyce and Ulysses by the time the complete novel was released.

The variety of literature surrounding the early marketing of modernism can provide insight into the lasting legacy of James Joyce’s Ulysses. It seems that Joyce consciously created an image of himself as a Great Artist and marketed Ulysses as an inaccessible masterpiece in order to generate mainstream interest. He was obviously successful in creating his legacy. However, I think the pretentious marketing of Ulysses hurt the novel in a different way. Perhaps, Ulysses’s reputation detracts from the beautiful depictions of humanity at the core of the story. Some people read the book to feel smart. Many people buy the book — without ever planning to read it — to look smart. Others are intimidated by the book and avoid it altogether. While the book certainly is difficult to read, Joyce’s insights into ordinary human experiences should not be lost for the grandiosity of the novel.

Advertisments in Ulysses

James Joyce’s Ulysses is an epic masterpiece and was always intended to be perceived as one. In 1681, playwright Nahum Tate described William Shakespeare’s King Lear as “a heap of jewels, unstrung and unpolished” that are “so dazzling in their disorder” (Tate). This quote may as well be about Ulysses which was first published, more than two centuries later, in 1918 as monthly installments in The Little Review magazine. With Ulysses, Joyce takes all the elements of Shakespeare’s reputation — inaccessibility, mastery of the English language, portrayals of timeless human experiences mixed with contemporary references — and amplifies them tenfold. Although The Little Review was ultimately forced to stop publishing Ulysses before the novel’s completion, The Little Review seems to perfectly capture the essence of Ulysses.

In the early twentieth century, many authors began consciously crafting personae to take advantage of the rising celebrity culture (Galow 315). Joyce seemed to be creating his persona as one of the greatest authors of the time. In “Scylla and Charybdis,” John Eglinton declares, “Our young Irish bards… have yet to create a figure which the world will set beside Saxon Shakespeare’s Hamlet” (Joyce 152). This may be a not-so-subtle hint at Joyce’s preferred legacy. The March 1918 edition of The Little Review, where the first episode of Ulysses is published for the first time, features Ulysses — and no other work in the magazine — on the front cover. Furthermore, the magazine introduces Ulysses by describing Joyce as “among the most significant literary creators of the day.” This presentation of Ulysses suggests that Joyce was deliberately positioning himself as the successor to Shakespeare’s unofficial position as the greatest writer of the English-speaking world. It almost seems wrong for an English magazine to be the way to success for a novel that is so focused on the British imperialism of Ireland. Yet, it also serves as a tangible representation of the complicated relationship between Ireland and England and of Joyce’s complicated feelings toward Ireland.

In “Lestrygonians,” Leopold Bloom sees a “procession of whitesmocked sandwichmen” advertising for H.E.L.Y.S. (Joyce 127). The men are directly compared to “that priest” Bloom encountered earlier that morning (Joyce 127). This passage demonstrates that Joyce — who was known for collecting advertisements — (Nadel 98) was conscious of the role marketing plays in all aspects of life. Bloom’s thoughts toward the men advertising for H.E.L.Y.S. also seem to devalue the Catholic Church. Bloom watches “Y, lagging behind, [draw] a chunk of bread from under his foreboard, [cram] it into his mouth, and [munch] as he walks” (Joyce 127). This action alludes to Eucharist and suggests that the influence of the Catholic Church is a result of excellent marketing. Similarly, The Little Review was concerned with outreach. They deliberately marketed themselves as “read by those who write the others;” however, they also worked to grow their influence. At the back of the March 1918 edition of the magazine, there is a blurb asking “every subscriber [to] get two or three new subscribers.” Ulysses’s place in The Little Review suggests that the book was marketed as a masterpiece for artists to experience and as a book that anyone should read.

In my opinion, had The Little Review finished publishing Ulysses, it would be the ideal form to experience the novel. The Little Review published Ulysses in small sections alongside other works making Ulysses approachable. Versions of Ulysses that are published as one volume are more intimidating due to the thickness and weight. The cover of the March 1918 edition of The Little Review also significantly contributes to the reception of Ulysses. The cover is serious — there are no graphics or unusual font choices; however, because of the bright colour, it is not boring. The grandiosity of Ulysses is important. It is a little pretentious, Joyce did effectively position himself as an equal to Shakespeare, and it is difficult to read. The Little Review promoted Ulysses as such. However, Ulysses also focuses on universal human experiences and emotions. The extraordinary elements of the novel and the ordinary elements of the novel contribute equally to the beauty of the Ulysses. The Little Review presents Ulysses in a way that helps readers focus on the mundane and personal aspects of the novel while acknowledging that it is a work of art.

Works Cited

Galow, Timothy W. “Literary Modernism in the Age of Celebrity.” Modernism/Modernity, vol.

17, no. 2, Apr. 2010, pp. 313–29. EBSCOhost,

https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/10.1353/mod.0.0191.

Golding, Alan C. “The Dial, The Little Review, and The Dialogics of Modernism.” American

Periodicals, vol. 15, no. 1, 2005, pp. 42–55. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20771170.

Leick, Karen. “Popular Modernism: Little Magazines and the American Daily Press.” PMLA,

vol. 123, no. 1, 2008, pp. 125–39. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25501831.

Nadel, Ira. “Marketing Modernism.” Modernism’s Second Act: A Cultural Narrative.

Palgrave Pivot, 2013, pp. 66-93. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137323378_4.

Tate, Nahum. "King Lear (Adapted by Nahum Tate) (Modern)." Internet Shakespeare Editions.

University of Victoria. https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/doc/Tate-Lr_M/scene/index.html.

Wexler, Joyce. “Who Paid for Modernism?” The Sewanee Review, vol. 94, no. 3, 1986, pp.

440–49. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/27545625.