Hagedorn Kara (Editions)

Research Rationale for 'The Corrected Text' of James Joyce's Ulysses

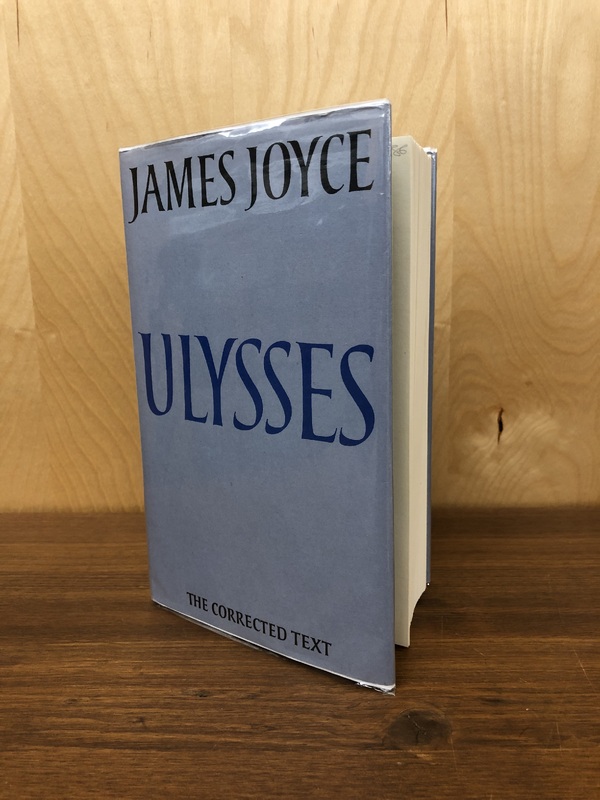

'The Corrected Text' of James Joyce's Ulysses (1986) consists of 649 pages and its spine measures 26 centimeters. The text's jacket's exterior has a gloss finish, while its interior flaps are matted. The jacket's colour is grey-blue, and the title page is formatted as follow: the text James Joyce is situated at the top of the cover and the text is black; the title Ulysses is set in the middle of the cover, and the text's colour is cobalt; finally, at the bottom of the cover is the subtitle 'The Corrected Text.' There is no accompanying image for the front of the text. On the reverse side of the book, placed at the bottom-center of the jacket is the barcode. The hardcover text holds 21 signatures and its covering's colour is cobalt. On the spine of the covering and located at the top is the title of the text and the author's name. Positioned at the bottom of the spine is The Bodley Head logo, the bust of Shakespeare.

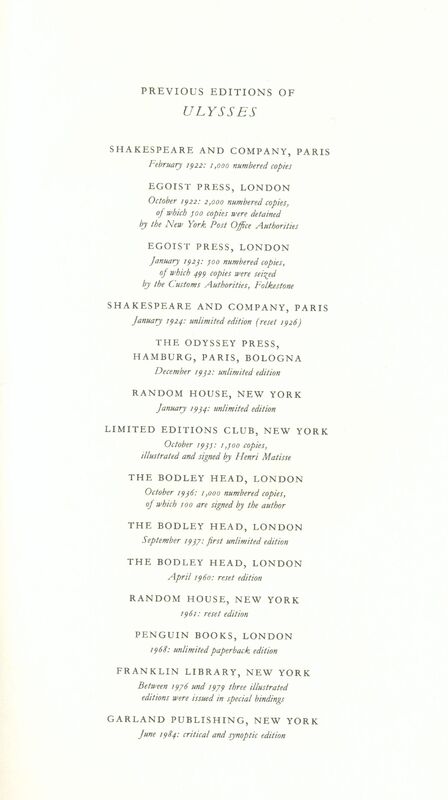

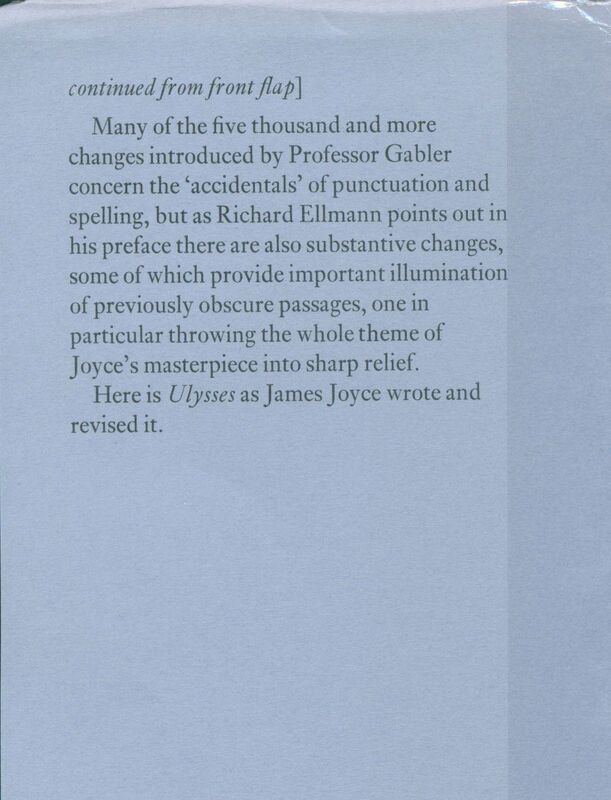

I selected the 1986 publication of James Joyce's Ulysses 'The Corrected Text' as my object because the tone of the summary that is written on the inside of the jacket. The summary begins with a quote from one of Joyce's letters to Harriet Weaver concerning the printer's errors that littered the first published edition. The corrected edition begins from this point of origin and boldly declares itself as the "non-corrupted counterpart to the first edition of 1922." Furthermore, the corrected edition "supersedes" all "subsequent texts" of the first edition. To audaciously declare one publication over the entire text's publishing history grabbed my attention. From this point on I was curious about the kind of author who would state their supremacy over the history of text. I am curious to research Walter Gabler's reputation as a scholar, the reception of his edition of Ulysses, and how his research method ordains this edition as superior to every edition that came before it. When Gabler's eidtion emerged in the Joycean literary landscape it caused quite a stir amongst literary scholars and textual critics, specifically Professor John Kidd. Once the edition was published, critiques of Gabler's method and claim rippled through the literary reviews and provided ammunition for scutinizing his edition. In effect, Gabler's controversial claims regarding his eiditon's literary purity brought him much attention. His methods of utilizing computer technology for textual organizing elevated his reupation amongst the literary critics as well. The New York Times article by Edwin McDowell, The New York Review by Charles Rossman, and The Washington Post article by David Remnick are all evidence of the breadth and scope of how affectual Gabler's text became.

What fascinates me about this literary artifact is how Gabler centralizes the idea of a text achieving a state of literary purity. By publishing a version entitled 'The Corrected Text,' the authors argue that it emits an aura that rivals the first edition. I believe that this desired state of literary sterilization relates to the themes of cleanliness and purification that run throughout Ulysses. Some of the most notorious aspects of Ulysses rely on the reader's capacity to feel disgusted and repulsed by Joyce’s portrayal of human fallibility. As a result, these moments leave a mark on the reader. Specifically, the discomfort Joyce elicits invites readers to explore the cultural relevance of disgust in relation to humanity. I do not have a concrete thesis for my project as of yet. However, I intend to explore this line of inquiry as I continue my research the intertextuality of 'The Corrected Text.'

Literary Review

In 'The Corrected Edition' of Ulysses (1986), Walter Gabler sought to decontaminate the text of errors that resulted from the typescript and proofs of the first edition. In doing so, he approaches Ulysses' publication history as a process that has contaminated the text. In effect, he argues that the human element has withheld the work from achieving a state of literary purity. By framing his publication as superior in this manner, he is practicing an element of Western aesthetics that Joyce parodies. Specifically, how the English language strives towards formal specialization. As a result, I connect Gabler's edition of Ulysses to Joyce's method of satirizing the anesthetization of language. Specifically, how Joyce explores the ideology of superiority in Western aesthetics by parodying modes of narrative in Cyclops. To investigate Ulysses through the lens of Western aestheticism and affect theory, then, requires a survey of its current academic landscape.

In "James Joyce and Italian Futurism," (1985) Corinna del Greco Lobner summarizes the history of the Italian Futurism, its publications, and Filippo Marinetti's influence from 1903-1920 (83). Lobner argues that the rhetoric on around war, violence, and hygiene in "Cyclops" are all parodies of Futurist diction. In "James Joyce: Triestine Futurist?" (1999), John McCourt surveys Futurism social climate in Trieste during 1903 to 1920. In doing so, he maps how Joyce's friends, acquaintances, and pupils intersected with the movement. Furthermore, his analysis presents a broader reading of how Joyce satirized Futurism's aesthetics in Ulysses. Specifically, in "Sirens," "Penelope," "Cyclops," and "Circe." Both Lobner and McCourt examine Ulysses in terms of how Joyce parodies the ideology of superiority of Italian Futurism. My approach to Ulysses extends Lobner and McCourt's analyses from the landscape of one aesthetic movement into the larger Western aesthetic continuum of narrative style. So, where Lobner and McCourt's analyses ends with Italian Futurism, I bring Ulysses into the larger scope of Western aestheticism. According to both authors, Bloom represents the anti-machismo of Futurism. Martha C. Nussbaum offers a similar reading of Bloom's aversion to self-destructive tendencies, but through affect theory. In her article, Nussbaum provides a philosophical examination of disgust and its ties to social marginalization. The author, then, ties her analysis to Bloom and how he internalizes his feelings of disgust. In essence, she argues that Bloom is the antithesis of what the ideology of superiority seeks to achieve. I agree with Nussbaum's approach to Bloom's character and method of moving through the world of Ulysses. However, Nussbaum's analysis lingers too heavily in the philosophical realm and does not relate her analysis of detachment and disgust to Joyce's narrative style. Although I agree with Nussbaum up to a point, the author fails to connect how the thematic element of detachment relates to the narrative of Bloom as a character. Compared to Nussbaum, though Daniel M. Shea, locates Joyce's examination of post-war aestheticism in Buck Mulligan. For Shea, Mulligan epitomizes the "de-humanizing effects" of l'art pour l'art (25). In doing so, Shea provides a robust examination of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and Ulysses as a continuum of Joyce's interrogation of aestheticism pre and post war. As opposed to a character analysis, Ariela Freedman applies an affectual lens to Joyce's imagery of "water and waste" (854). By comparison, Freedman argues that through the "evocation" of these tropes, Joyce is "speculating" on the "relationship between aesthetics and history" (854). By elevating Joyce's use of these tropes, Freedman brings Ulysses in closer conversation with 21st-century aesthetic analyses. Concurrently, my analysis relates to Nussbaum and Shea's affectual exploration of Bloom and Mulligan, along with Freedman's examination the imagery of water and waste in the text. Where these three academics engage with Ulysses' imagery and character analysis via affect theory, my scope brings Joyce's narrative play to the field. Furthermore, it is in the space of narrative style and its formulation that I situate my analysis and my approach with Gabler's edition simultaneously. Indeed, my topic of investigating Joyce's satire of aestheticism through affect theory bring together two academic communities: affect theory and critical ideology.

The result of examining Ulysses through this layered landscape of style and the structure of Western aestheticism, invites theoretical frameworks to cross-pollinate. In Ulysses, Joyce plays with the structure in which language evolves. He does so through how narrative style transforms throughout the text. To understand what affect the narrative changes elicit in the text, how they function, and how they relate to Western literary modes requires a nuanced approach to the text. Numerous academics have already created the expansive literary landscape that consists of analyzing Joyce's work. However, my hope is to bring together these two realms of theory into 21st-century Ulysses studies.

Walter Gabler's Edition of Ulysses 'The Corrected Edition' and Joyce's Irony Towards Language

For 'The Corrected Edition' of Ulysses (1984), Walter Gabler sought to extract the text's typescript and proofs of errors that resulted in its subsequent editions. In doing so, he approaches Ulysses' process of publication that has contaminated Joyce's original intentions for the text. In effect, he argues that with every new edition, the human element interfered with the text's ascension of achieving literary purity. By framing his publication as surpassing all other editions, Gabler is pushing a literary agenda that Joyce parodies in Ulysses. Specifically, how English language strives for formal purification to achieve ideal representation through technical phraseology. As a result, I connect Gabler's edition of Ulysses to Joyce's method of satirizing the anesthetization of language. Specifically, Joyce's parodies of modes of narrative in "Cyclops" and the effects of spatial sterilization.

In "Cyclops," Joyce uses medical technical language completely out of its context when Bloom tries to explain a natural phenomenon. By doing so, the displaced language effects the narrative space of the characters and the continuity of the stylistic elements in the text. As a result, the language becomes its own mode of ostracization because of how it strives towards technical specialization. Furthermore, the discourse is so out of context that its displacement completely erases Bloom's voice from the space of the narrative. In doing so, the narrator's parody of language, by its very mechanisms, ostracizes Bloom from the narrative. Furthermore, as the language covers a vulgar description, the very tone of the medical language parodies its own seriousness. Such sterilization of the narrative space ties into Gabler's desire for his edition to "stand on its own merits" as a text (Joyce 649). For example, there is a conversation regarding Joe Brady's "poker" posthumously "standing up" (12. 560-1). As Haynes, the narrator, Doran, Bergan, and the Citizen all have a laugh, Bloom attempts to explain the nature of such "phenomenon" (12. 565). As Bloom tries to contribute to the conversation, he is continuously kept from finishing his sentences. Specifically, the Nameless narrator mocks Bloom by cutting off his voice on the page. For example, he states: "And then [Bloom] starts with his jawbreakers about phenomenon and science and this phenomenon and the other phenomenon" (12.466-7). In this instance, the Nameless first-person narrator ridicules Bloom's attempt at trying to explain how a penis can erect itself following an execution. By sneering at Bloom's desire to contribute to the conversation, the narrator's contempt shifts the entire style of the text. In particular, the narrator uses medical language to mock Bloom's explanation. For example, the narrator uses esoteric medical language to describe how the "instantaneous fracture of the cervical vertebrae" can create a "ganglionic stimulus" (12.696-72). The passage becomes even more satirical when the medical description turns to Latin phraseology like "corpora cavernosa" and "in aticulo mortis per diminutionem capitis" (12.474-8). In this instance, the medical language is so out of the context from which it came that its specialization becomes the site of parody. Moreover, the technical jargon appears garish in relation to the site of the conversation. That is, a group of friends sitting in a pub coming together and having a laugh over life's absurd moments. Hence, the description of an erect penis is so sanitized by the phraseology, the medical language no longer comes across as legitimate. Indeed, the medical terminology is so out of context that the language itself is obscene with its hubris towards the conversation's content. The sanitizing effect that encapsulates in "Cyclop's" narrative style does not remain at the surface of the plot either.

Accordingly, the linguistic abstraction in "Cyclops" also represents Bloom's figurative abstraction in the narrative space. For example, as a Jewish man, the narrator attempts to sterilize Bloom's voice from the space of the "I's" narration. Indeed, the narrator keeps Bloom state-less in the conversation by cutting off Bloom's voice as he is trying to make a statement. In other words, through the stylistic shifts in the narrative voice, Bloom's existence is completely uprooted from the text. To extract a single character from their contribution to the conversation disregards how they shape the environment. Similarly, when Gabler states that his intention of extracting the "corruptions" at the "root" of the work, he is sanitizing the text from its entire publishing past. For example, Gabler's method of creating "the best possible" version of Ulysses means he referenced the text's material "before [the] corruptions occurred" (649). In other words, 'The Corrected Text' goes back to a time when the text was in motion of becoming. Such methodology disregards the context in which errors make their way into the published version. In other words, errors that occurred during the text's publishing lineage shape how the text is received in its time. By detaching the text from its own genealogical history undermines the ways in which a text evolves through its materiality. Although Joyce could not foresee the future of Ulysses' publications, there is irony imbedded in Gabler's methodology. Indeed, the irony of an editor trying to decontaminate Ulysses of publishing errors would have had Joyce rolling.

Work Cited

Freedman, A. “Did It Flow?: Bridging Aesthetics and History in Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’” Modernism/modernity (Baltimore, Md.), vol. 13, no. 1, 2006, pp. 107–22.

Joyce, James. Ulysses 'The Corrected Text.' Walter Gabler, London, The Bodley Head, 1986.

Lobner, Corinna del Greco. “James Joyce and Italian Futurism.” Irish University Review, vol. 15, no. 1, 1985, pp. 73–92.

McCourt, John. "James Joyce: Triestine Futurist?" James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 2, 1999, pp85-105. EBSCOhost, http://search-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.liberary.uvic.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=2000057132&login. asp&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Nussbaum, Martha C. "Between Detachment and Disgust: Bloom in Hades." Joyce's Ulysses: Philosophical Perspectives, edited by Philip Kitcher, Oxford University Press, 2020, pp. 29-62. EBSCOhost, http://seachebsconhostcom.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/login.aspx?direct=true&db=mzh&AN=202019531529&login.asp&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Shea, Daniel M. "From 'god of the Creation" to "Hangman God": Joyce's Reassessment of Aestheticism." Art and Life in Aestheticism, edited by Kelly Comfort, Palgrave MacMillan, 2008, pp 125-138.