Morin-Goodwin Annie (Little Magazine)

Rational for Donation Pleas in "The Little Review

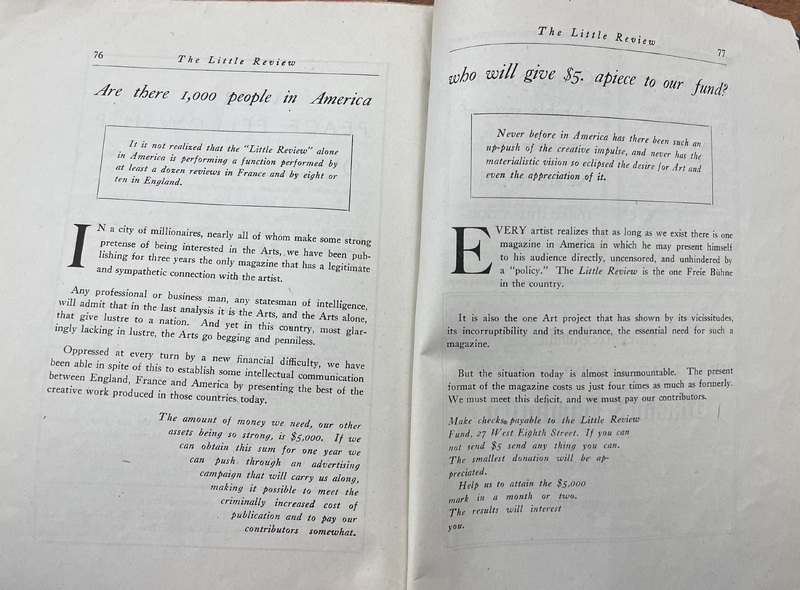

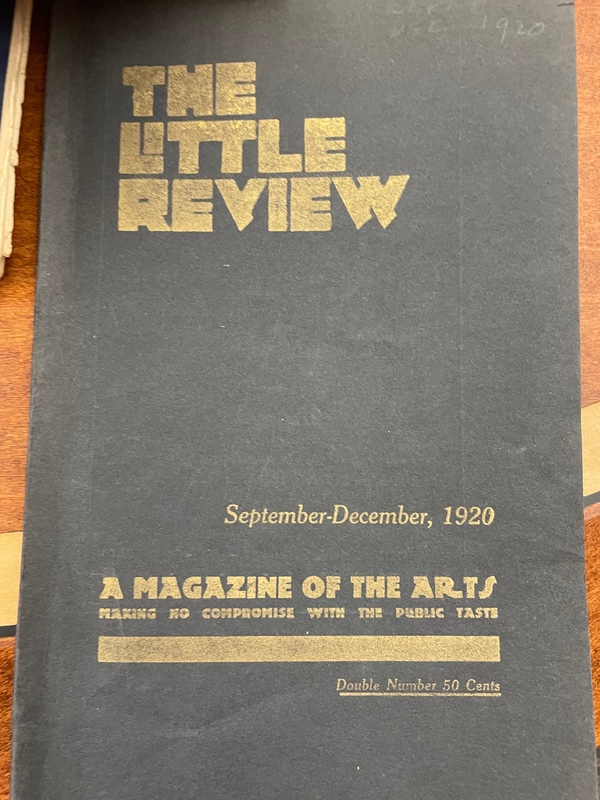

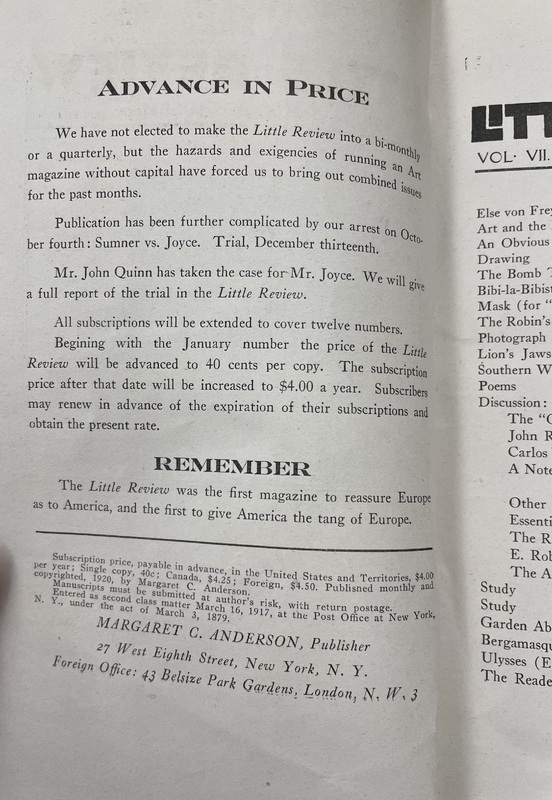

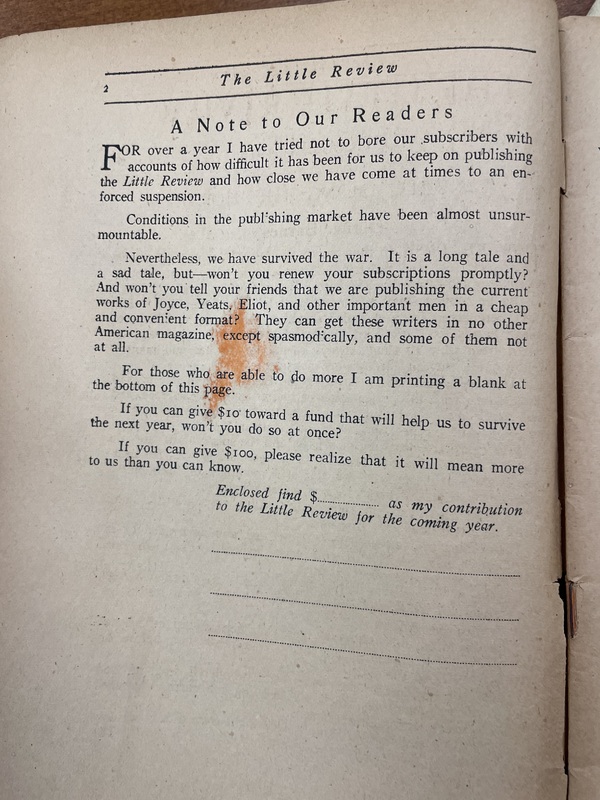

The archives I have decided to examine are some copies of “The Little Review” from early 1919 to 1920. “The Little Review” was a subscription based publication that posted current literary works and reviews, along with subscriber opinions. What I am most interested in examining, however, are the various writers' notes sprinkled through the monthly editions. In copies from as early as December 1918, there are messages from the author pleading with readers for donations, renewed subscriptions, and recommendations to friends. In a September - December, 1920 edition, a two page spread is included asking readers to help them hit a $5000 goal to continue publishing in the new year. There is a page stating that The Little Review is “the only magazine that has a legitimate and sympathetic connection with the artist,” and that “the Arts go begging and penniless.” In another edition from March 1920, a page in the back is reserved for an explanation as to why readers might not receive a January edition. In this, the writers state that the home they publish out of has been sold and they are on the hunt for new headquarters. The author also states that the two of them running the review are recovering from influenza and that their financial situation has not improved. There are various other copies of “The Little Review” with different methods of asking for donations, however, I will be focusing on the two page spread from September - December, 1920.

The pleas for money from the publisher of the paper, with emphasis placed on the lack of money in Arts, reminds me of Stephen Deadlus. An educated man, working a respectable job as a teacher who can barely make ends meet. I believe examining these donation pleas in “The Little Review” can provide a better understanding of life in the twentieth century, particularly for artists, readers, and writers. Examining the socio-economic state of the world Joyce lived in while writing Ulysses will provide deeper insight into Joyce’s life, and what he is trying to tell readers about life as an artist at the time. To dig deeper into this, I will be examining the financial state of the arts. How was art funded?. What was the general opinion on the arts? Were people not interested in consuming it, or was there simply no money to be spent? Who were the people who could spend money supporting the arts? Since Joyce was a novelist, answers to these questions will explain choices made in Ulysses, specifically about Stephen Deadlus. Did Joyce write Stephen, a broke, selfish, artist, as a reflection of the lack of funding in the arts he was seeing?

Literary Review

Inside 100-year-old copies of The Little Review, a literary magazine, a commonality can be found throughout the issues. Different forms of pleas for donations are littered throughout the copies.

When examining why a private publishing company might need to ask for donations, first we must consider how publishers made their money. “The Reader as the Consumer” studies how Curtis Publishing Company started a now common practice of selling the readers to advertisers. The company owned “the two widest-circulating magazines of the 1910s and 1920s” (Ward 47); Ladies’ Home Journal and Saturday Evening Post. An image of the ideal consumers began to form in the publisher's eyes, and they sold this idea to the advertisers. Soon, however, they faced “scrutiny of advertisers who wanted proof of its readership claims” (Ward 47). Thus, began deeper research into audiences and readers to be sold to advertisers as a promise of returned investments. With a clear picture of who is consuming media, advertisers can now specify their ads to that audience.

With the precedent for specific advertising now set, advertisers are looking to make profitable returns from their investments. This, however, coincided with the rise of modernist literature, a wave of writers who disliked the state of the world and decided to write with no consideration of the reader. Modernist writers felt as if they should not pander to their readers and because of this, writers were refusing to censor or edit their work to make it publishable (Wexler, Who Paid… 441). Meanwhile, publishing became a less profitable industry, “until World War 1, 3000 copies constituted a standard first printing for a novel. In the 1930s, 3000 copies would make a novel a highbrow best seller” (Wexler, “Modernist writers…” 290). With the decline of profits, publishers turned to safer literary works. Uncensored literature now had to turn to private presses, such as The Little Review, to publish their work. The private publications did not have to abide by censorship laws (Wexler, Who Paid… 447), however, they were unable to use targeted advertising, thus making less income. This could be why so many copies of The Little Review had to ask for donations.

With the context of the financial and legal state of publishing, we can now ask the question of how Joyce’s frustrations with publishing companies appeared in his character, Stephen Dedalus. It is widely assumed Dedalus was written as a loose representation of Joyce himself. Like Dedalus, “[Joyce’s] mother suffered from cancer… Joyce also refused to kneel and pray by his mother's bed and felt guilt afterwards” (Edmundson 546). Edmundson explains that the character of Dedalus is riddled with guilt, which is conveyed through drowning imagery, which could have been written as a reflection of what Joyce was feeling himself. Rickard’s “Stephen Dedalus Among Schoolchildren” dives into the character's profession as a teacher and his disdain for authority, both of which are traits of Joyce.

With the connection between Joyce and Dedalus now evident, we can be left to wonder if Dedalus’ financial struggles reflect Joyce’s growing frustrations with the publishing process and the lack of funding in private publishers. The comparison between Joyce and Dedalus can now deepen our understanding of Ulysses. Joyce’s Ulysses is so beloved partly due to its nuanced take on life in 1910s Dublin. Through Joyce’s struggling artist character, Dedalus, we now have insight into some of Joyce’s personal struggles with being published and beliefs on the state of the world at the time, which is what makes the book so special.

How Publishing Impacted James Joyce's Ulysses

In an American literary magazine from the 1910s, called “The Little Review”, there are multiple, full-page pleas to readers for donations to keep the magazine afloat. The need for the magazine to ask for donations begged the question of how the arts were funded during the time. In my research, I found that most major publishing companies made their money through targeted advertising, much like today. Since modernist writers wrote with no intended readers, they had no marketable target audience. This, along with the refusal to abide by censorship laws, made most modernist literature only publishable through private, less funded publishing companies like “The Little Review.” With Joyce’s growing frustrations with publishing companies in mind, how can we see frustration manifest in Ulysses, and the character of Stephen Dedalus?

Stephen Dedalus is widely accepted as a loose representation of James Joyce in his twenties. Assuming Joyce wrote pieces of himself in this character, we must wonder if any of the issues surrounding literature and publication at the time also materialized in Dedalus, an aspiring, yet underappreciated author. One of the very first things we learn about Dedalus as a character is his financial struggle. When Stephen meets with his boss, Mr. Deasy, to collect his pay and is instructed to buy a wallet, he retorts that “[His] would often be empty” (ep 2 line 250). When Stephen receives his measly pay, he lists off his debts (ep 2 line 255-259) and realizes he can't even begin to pay them off. Dedalus’ struggling financial state could reflect the difficulty Joyce was finding working with publishers. To make any money off his work, Joyce had to work with publishers who had issues with his vulgarness. Since Joyce refused to censor, he often faced conflict with publishing companies and had to turn to the less profitable private publishers, such as “The Little Review.” This difficulty with profiting off his work could be why Joyce wrote Dedalus as financially struggling, as the publishers he was working with were also struggling.

Connections between Joyce and Dedalus can also be made in ways of their appreciation. Throughout Ulysses, Stephen is often looked down upon by his peers despite his intelligence. This is most portrayed by Buck Mulligan, who in episode one, says, “wait till you hear [Stephen] on Hamlet” (ep 2 line 487), following with “Wait until I have a few pints in me” (547-548). Dedalus’ theories are undermined once again when he is in the library with other scholars in episode nine. Russell exclaims condescendingly that “the supreme question about … art is out of how deep a life does it spring … All the rest is the speculation of schoolboys for schoolboys'' (ep 9 line 49-53). Dedalus is burned again when he discovers that Russell has not invited him to contribute to his scholarly work but has invited Mulligan and Haines to contribute. When Stephen asks Russell to pass on a letter, he is turned down when Russell says, “we have so much correspondence” (319). Stephen is not accepted as an equal by these men, despite his intelligence. This reflects Joyce’s real-world difficulty in finding publishers. Joyce’s refusal to censor or take notes on his works illustrate that he thinks very highly of himself, however, his difficulty in finding publishing could have made him feel undervalued and underappreciated. This could be why he wrote Dedalus as such. The pleas for donations in “The Little Review” are evidence of what issues publishing as a whole had at the time with censorship and lack of funding. In Ulysses, specifically in Dedalus’ character, we see Joyce’s frustration with such issues. Dedalus’ lack of respect could be a reflection of Joyce’s self perceived disrespect from major publishing companies who refused to work with him and Dedalus’ money issues could reflect Joyce’s frustration that the publishers who would work with him, such as “The Little Review” had money troubles.

Finding these donation pleas in “The Little Review” say a lot about Ulysses, funding of the arts at the time of publication, and life in the 1910s as a whole. Seeing the abundance of growingly desperate appeals to readers for some money in a magazine that is publishing one of the greatest novels of all time is quite interesting. The pages beg the question of how publishing made money, why Joyce was using publishers who were barely staying afloat, and how did Joyce’s difficulties in the literary world manifest themselves in Stephen Dedalus, a loose representation of Joyce? These donation pleas give us a greater understanding of what life was like when Joyce was composing Ulysses, which helps us gain insight into the novel.

Works Cited

Edmundson, Melissa. “Love's Bitter Mystery”: Stephen Dedalus, Drowning, and the Burden of

Guilt in Ulysses. English Studies, 2009, pp. 545-556.

Rickard, John. “Stephen Dedalus Among School Children: The Schoolroom and the Riddle of

Authority in ‘Ulysses.’” Studies in the Literary Imagination, vol. 30, no. 2, 1997.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Edited by Hans Walter Gabler, Random House UK, 2022.

Ward, Douglas. “The Reader as Consumer: Curtis Publishing Company and its Audience, 1910–

1930” Journalism History, 1996

Wexler, Joyce. “MODERNIST WRITERS AND PUBLISHERS.” Studies in the Novel, vol. 17, no.

3, 1985, pp. 286–95.

Wexler, Joyce. Who Paid for Modernism?: Art, Money, and the Fiction of Conrad, Joyce, and Lawrence. University of Arkansas Press, 1997.