Signs on a White Field: The Shadow of Ulysses

Erin Kroi

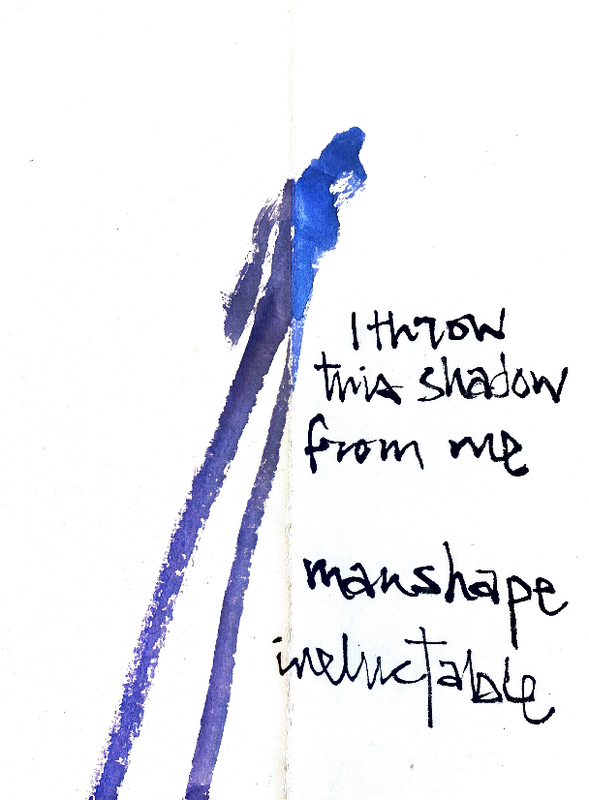

The object that piqued my interest and produced a cacophony of inquiry was the shadow of Stephen Dedalus, illustrated by Robert Amos. Stephen’s shadow is a small fragment of Amos’ large, unfolding work, Dedalus on the Shore(2016), a contemporary reimagining of a modernist moment. My perspective of Amos’ illustration converges with my experience of Ulysses, and I am transported to the nearly final moments of “Proteus,” the labyrinthine episode stimulated by the introspective journey of Stephen Dedalus, while he walks along the Sandymount Strand. I consider the intimacy of my own relationship to the text that forms the painting, and the knowing power I possess over a viewer unfamiliar with the Joycean context. Amos’ work coagulates from the literary canon; arguably, therefore does its meaning. But the so-called power I contemplate barricades the aesthetic experience, and the possibility of meaning, with cultural capital. The painting, without its literary context, remains a work of art, subject to consideration and the desire to find meaning within it. After all, the painting is entitled Dedalus on the Shore, yet it does not picture Stephen in physical form. The work pictures Stephen’s shadow, moving along the unravelling parchment shore, a vaguely man-shaped form composed of blue watercolour. Not Dedalus himself, but his imprint. The implication of him unbound by the limitations of form. Truthfully, a better indication of his rootless identity and consuming trajectory of densely saturated thought than any rendering of his actual form could have expressed.

Ineluctable modality of the visible: I retrace Amos’ work, lending my experience of Dedalus on the Shore to my experience of visual sense. Minimal. Focality concentrated in near-translucent man-shapes and ink splatterings, the rest deflected by negative space. Without the scatterings of text from Ulysses, the imagery does not divulge its context. Independent from the conception of a Stephen Dedalus, without swarming fragments of Ulysses composing interpretations of the work, the contextual gap endues a possibility created in the impact of an interpreter’s experience with a work of art. In an attempt to redirect my view of Dedalus on the Shore from the context of Ulysses, I inadvertently exposed the contextual vacuum between myself and the novel I love. My current exploration is a surrender to the intuitive experience of Ulysses, believing that this non-linguistic dissection derails the decay of the text by reinvigorating what can be made of it. I illuminated the divergence of my own experience from the world of Joyce and his modernist work in an effort to immerse myself in a discussion of context and affect. Here is an illustration of personal context, emblems on a page that convey the form of my experience, albeit void of the substance of character: I am an Albanian settler on unceded Canadian soil, a queer woman, contemporary. I hold my own context up to that of Ulysses and examine: an English novel composed in Paris, Zurich, and Trieste, by a heterosexual, male, Irish author, officially published in 1922. The distance between myself and Ulysses is expounded by geography, identity, ideology, and a century. Where contextual commonality propels aesthetic pleasure, here is a chasm. Yet, my affection for the novel is irrefutable. I love it. Further, I see myself within it.

My line of inquiry gains traction by considering the image of Stephen Dedalus as not the man but the shadow, and then contemplates Ulysses as not the novel, the object within its context, but as the abstract imprint cultivated through the novel’s gyration through ever-evolving contexts. The shadow is the nexus between the physical and the mythical: it is one object's residual imprint onto another. It is not an original object itself, but an indication of how objects exist in overlay. The shadow is immaterial, phantasmagorical; a mirage beholden to the swift transfusion of time and light from an object to an observer. It is inseverable from and dependent upon the existence of a material object, which exists in some form of the present. We cannot completely interpret a shadow without the acknowledgement that it has an original form, however, we can acknowledge a shadow as a singular thing. We see the shadow of Stephen Dedalus and know that there exists a Stephen Dedalus that is the shadow’s original context. However, as Amos illustrates, we do not have to examine the body of Stephen Dedalus himself to make something of his shadow, independent of his original body, yet born from it. A freshly cultivated image dispatched from, yet true to, original form.

In Rita Felski's "Everyday Aesthetics," she discusses Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology, an experience of an object, and the appearance of an object determined by experience. She applies phenomenology in criticism of literary and cultural study’s tendencies to embellish the facts of experience with mystifying qualities, rather than address that semiconscious perception is the reality of everyday aesthetic experience. Felski posits that, “what renders phenomenology a still timely framework is not Husserl’s attempt at a transcendental reduction—one more expression of a recurring philosophical ambition to escape one’s own shadow—but the gaze of wonder it directs at ordinary objects and mundane forms of feeling and thought. Its aim is to really see ordinary structures of experience—not in order to celebrate them or to trumpet their authenticity, but to gain a surer grasp of the ineluctable nature of our first-person relation to the world”(Felski 174). I extend Felski’s assertion of a commonplace aesthetic experience to Amos’ hypothetically decontextualized painting, then further from the shadow of Dedalus to the shadow of Ulysses. The text is formed from an explosion of literary and historical allusion. Joyce’s dense saturation of high literature weaves his modernist work into the catalogue of high-literary history that moulds it. Analysing the frames of reference within the text allows us to find hidden meaning, but is not necessarily the meaning of the text. As Dedalus contemplates the limitations of his own shadow, the Shadow of Ulysses explores the expansion of Ulysses, liberated from the search for employed meaning, and reproduced through the possibility engendered by intuitively transformative reception. Existing discourse is ample, and much can be further said about allusion in Ulysses, though I leave the task of extracting the traces of history to others. Rather than explore the canonical impact of Ulysses, I endeavour to explore the impressions the novel leaves on the commonplace experience. The shadow of Ulysses, the imprint of the novel that endures, is rendered not through an active expedition in search of meaning, but through our intuitive experiences of the text. In accordance with Felski's assertion that art is “worldy, not otherworldly: not ineffable, untranslatable, or other,” I believe there is a vitality to Ulysses, unbridled by cultural capital, that is active and regenerative. This vitality is not elusive, or arduous to identify. It is not shrouded by belletristic projections decrypted through the literary canon, or else auspiciously unveiled in dreams. It can be named, and is named in representations of the text that do not proclaim, “I have read the novel; I am of those well versed in its context,” rather, “Here is what I make of the novel, with what it has made of me.”

The Shadow of Ulysses is a phenomenon engendered by reception, not the culture contained within the text. Defining the Shadow of Ulysses requires exploration of the readership onto which images of Ulysses are cast, and whose individualised extrapolations of meaning render Ulysses an intuitively powerful work, not alone an intellectually reverberant one.

In The Illicit Joyce of Postmodernism: Reading Against the Grain, Kevin J.H. Dettmar reassembles the works of Joyce through a postmodern lens. His is an endeavour to indulge in the mystery of Joyce, rather than the mastery. He states that, “Ulysses is certainly a modernist classic,” yet, centres his discussion of the text on “its playful unwillingness to take itself or its modernist devices too seriously”(Dettmar 11). Rather than extrapolating the meaning of Ulysses from the fragments of literary history or evidence of Joyce’s voice within the text, Dettmar regenerates a personalised Ulysses, “less interested in philosophical consistency than in discovery and delight”(Dettmar 2). Dettmar’s warping of theoretical lenses is less an advocation for a postmodernist Ulysses than it is exemplary of the vibrant and varying impressions of Ulysses. He demonstrates that while the physical text of Ulysses is unchanging, the meanings extracted from the text are unlimited, placeless, and subject to constant change.

Through similar mechanisms of manipulated perception, scholars such as Eishiro Ito and Krishna Sen regenerate Ulysses through cultural reception. They reclaim the text, unveiling impressions which can be credibly excavated, but in secluded, traditional examinations, are neglected. Eishiro Ito’s article, “United States of Asia; James Joyce and Japan” depicts a Joycean Japan, exposed through “the Japanese reception of Joyce from a postcolonial perspective.”(Ito 194). Similarly, Krishna Sen unveils “ancient Indian philosophical and aesthetic systems“ through expressions of epiphany in Ulysses (Sen 213). Both Ito and Sen briefly touch upon the relationship between Joyce’s European modernism and Japan and India during the fabrication of Ulysses. However, the Ulysses made perceptible through their expositions is rendered through their transformative receptions of the text.

In “Polysystems and the Postcolonial: The Wondrous Adventures of Jame Joyce and his Ulysses Across Book Markets,” Ira Torressi unravels Ulysses through the novel’s migration “from the periphery to the centre of polysystems worldwide”(Toressi). The article’s most prominent insights contemplate generally how the extensive translation of the text enables the repossession of a distinctly Irish and modernist cultural marker across the globe. “Translation,” she states, “can be a powerful actor of change in the original polysystem from which a work and/or author originate”(Toressi). This Ulysses does not belong to a nationality, but to a possibility generated through diverse dispersion.

The shadow of Ulysses liquifies as individual illustrations of extrapolated meaning dilate into reimaginings of the text. In “Seeing James Joyce’s Ulysses into the Digital Age,” Hans Walter Gaber reflects on the fabrication of Ulysses: A Critical and Synoptic Edition(1984); an exercise in textual criticism and genetic editing that erupted tempests over the constituents of a “definitive” edition of Ulysses, determined by replication most authentic to original form. In defence of the edition, Gabler posits, “It is the edition's underlying conception that the text of the work Ulysses extends in time over the range of its material inscriptions. Hence, the edition offers the text of Ulysses in two guises: as a reading text, yes; but mainly as an edition text to be experienced diachronically, that is, in its temporal depth”(Gabler 30).

Each scholar accounts for the cultural significance encompassed in the absorption of Ulysses, and the choice to approach the mystifying text. Yet, each scholar diverts focus from the novel’s literary history to the influential power engendered by its essence, and our delight in its stylistic whims. The forms and frameworks through which we derive meaning from the text are susceptible to regeneration and decay, the ability to derive meaning from the text expands, endures.

I return from the various reflections on the text to the genesis of a residual Ulysses, the catalyst of my swarming reflections on Amos’ work, to meet Dedalus on the shore. Upon viewing his shadow, Stephen’s internal monologue is propelled by the recognition of his physical form’s imprint before him. He calculates, “manshape ineluctable.” Stephen’s shadow, as he perceives it in his present experience, is limited. It is reduced to a mark on the ground determined by the confines of his shape. It is inseverable from his present form, therefore inevitably restricted to his own perception. Stephen moves from calculations of the tangible and present sensory experience to ponder potentiality. “Who watches me here? Who ever anywhere will read these written words?” Stephen hypothesises a viewer of his present moment. His shadow made immovable in the sand, impressed into the Sandymount Strand beyond his expedition across it. Stephen’s shadow is equated to his poetic scraps, a formal element extending from his person, composing a residual Stephen Dedalus. Markings reduced to physical shapes, ended by the momentary measurement of their composition.

Stephen unites his actuality with his potential, liberating his thoughts from a hopeless destiny, ejecting “Endless.” An endlessness empowered by Stephen’s relinquishing of power, or rather, acknowledgment of nonpossession over the transcendence of his ineluctable manshape into an endless form of his form. The possibility of endless, Stephen recognises, is realised by a viewer. Throughout the portions of Ulysses stimulated by Stephen’s internal monologue, we see a character devised referentially, and a mind formulated from second-hand thoughts. The form Stephen recognizes in the sand is intellectually energetic, but not yet singularly impressive. The endless impression Stephen longs to envision can only be projected from the residue of his form by an interpreter.

Stephen’s ruminations are gratified by the various modes of transformative receptions of Ulysses, but I do not hope for my reflections on Dedalus on the Shore to be ended with assessments of Ulysses consumption. The Shadow of Ulysses is not merely an encapsulation of the novel’s varied reception throughout its unfolding in time; it is a statement about the possibility of seeing oneself within the vortex of reflections. The act of transformative reception is a testament to the endless quality of the novel, one mode through which Ulysses is stripped from its ended context, engendering its enduring imprint. Not that we absorb and regurgitate Ulysses in commemoration of its literary stature, but because we are capable of deriving individualised meaning, spiting the illusory confines of context.

In “Interpreting as Relating,” Felski writes, “what we choose to decipher, how we decipher it, and to what end––these decisions are driven by what we feel affinity for, what resonates”(Felski 128). With this in mind, I am moved from the markings on my own page to the markings on Stephen’s paper: signs on a white field. I meet my intimacy with Ulysses––my own context so far removed from that of Joyce’s modernist world––not reaching around my experience in search of extrapolated meaning, but through it in search of truth. To name every impression the text has made on my experience would be to dissect every word from the pages of Ulysses, but what I make of these impressions is visible here. Like anyone who’s motive engine is an ambition to create, I interpret the immutable manshape of Stephen Dedalus, and the ended text of Ulysses, and encounter myself. Calculating the confines of potential, wondering if I might ever be seen.

Literature

Dettmar, Kevin J. H. The Illicit Joyce of Postmodernism: Reading Against the Grain. Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1996.

Felski, Rita. “Everyday Aesthetics.” The Minnesota Review, vol. 2009, no. 71–72, 2009, p. 171.

Felski, Rita. “Interpreting as Relating.” Hooked: Art and Attachment. University of Chicago Press, 2020, pp. 121-163.

Gabler, Hans Walter. “Seeing James Joyce’s Ulysses into the Digital Age: Forty Years of Steering an Edition Through Turbulences of Scholarship and Reception.” Joyce Studies Annual, vol. 2018, no. 1, 2018, pp. 3–36.

Ito, Eishiro. “United States of Asia: James Joyce and Japan.” A Companion to James Joyce. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Oxford University Press, 2022

Sen, Krishna. “Where Agni Araflammed and Shiva Slew: Joyce’s Interface with India.” A Companion to James Joyce. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Torresi, Ira. “The Polysystem and the Postcolonial: The Wondrous Adventures of James Joyce and His Ulysses across Book Markets.” Translation Studies, vol. 6, no. 2, May 2013, pp. 217–31.

Visuals

Amos, Robert. Dedalus on the Shore, 2016.

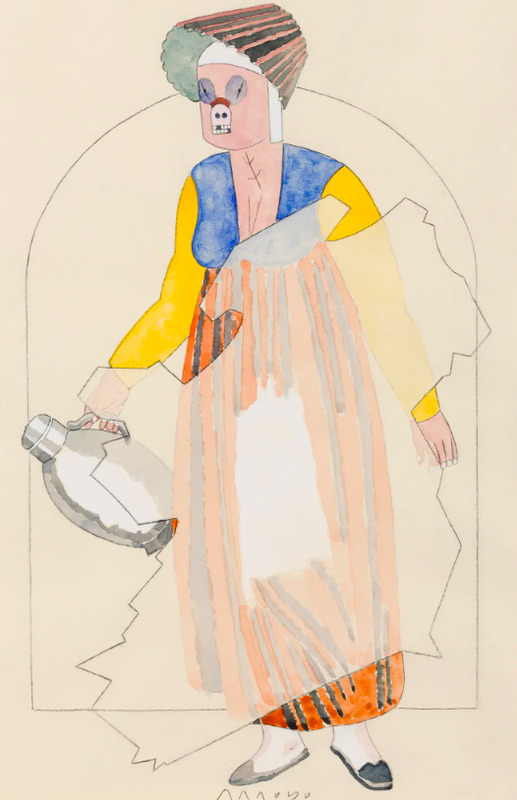

Arroyo, Eduardo. Ulysses, 2022.

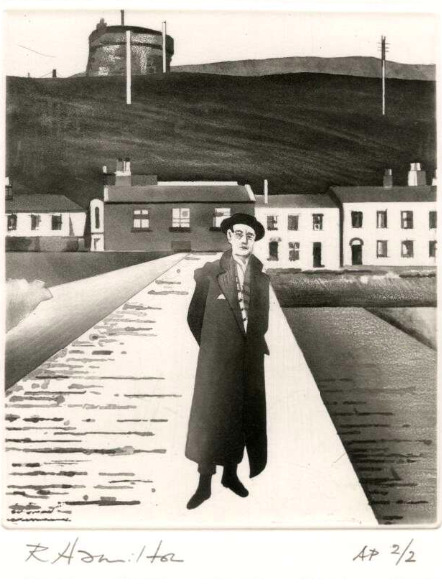

Hamilton, Richord. “Sandycove.” Ulysses, 1988.

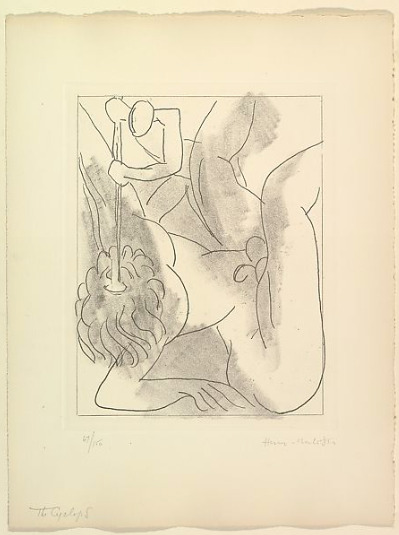

Matisse, Henri. Ulysses, 1935.

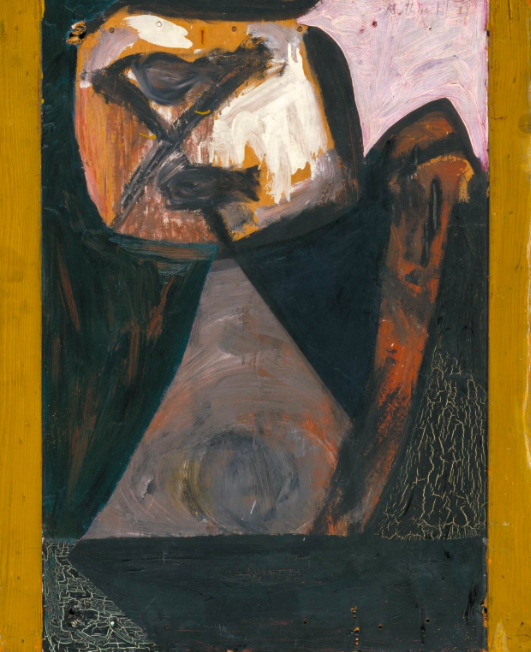

Motherwell, Robert. Ulysses, 1947.