Meldrum JP (Sound)

Description of Object:

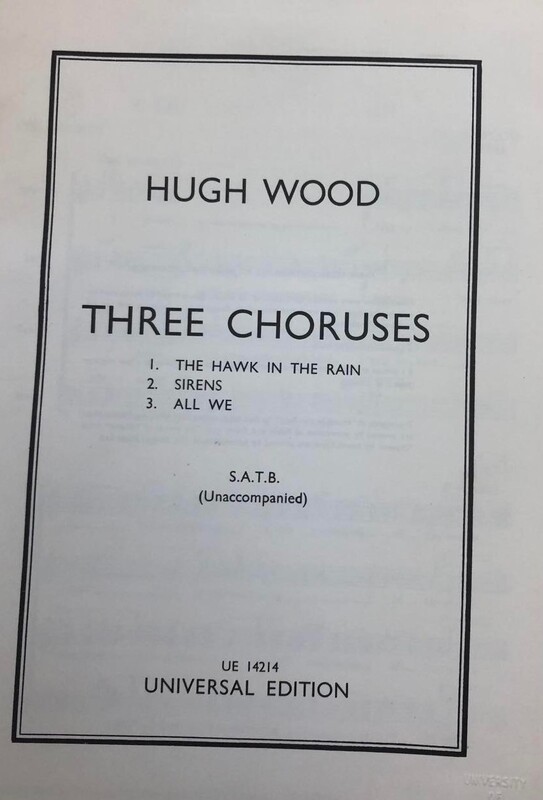

Hugh Wood’s Three Choruses is a trilogy of choral scores using lyrics derived from early 20th-century United Kingdom writers Ted Hughes, Edwin Muir, and James Joyce. The object is a black-and-white scorebook. The bordered title page lists the composer, the title of the collection, and the three pieces within: “The Hawk In the Rain”, “Sirens”, and “All We”. Below the title is “S.A.T.B.”, an indication that the piece is meant to be unaccompanied other than the traditional choral voices: Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass. The page indicates the object was published by Universal Editions, although their website catalog lists no work by Hugh Wood as of late. The forward gives instruction to the performers that the work is intended to be sung with 16 voices, indicates unique notation within the score, and notifies the reader of permissions given to use the words within the pieces. Joyce’s words are entitled to Wood by The Bodley Head Ltd.

The piece pertaining to James Joyce’s Ulysses, “Sirens”, is written in four parts intended to be sung by the aforementioned four voicings with three voices per part, totaling 16 as stated in the forward. Joyce is credited for the arrangement, while the two other writers contained in Three Choruses are listed only by name above the score. The lyrics are composed of fragments from repeated phrases from “Sirens”, the eleventh episode of Ulysses.

Reasoning and Argument:

I choose this object for two chief reasons. The first is an undying passion for music. This assignment is an opportunity to, simply put, write about music. The second reason is to use this object as a jumping-off point to analyze and research the extensive lyricality and musicality in Ulysses. I hope to argue, in essence, that Joyce is attempting to use language and the written word to reach the expressiveness of harmony and melody. The “Sirens” chapter is unfathomably musical, and the novel-altogether is loaded with italicized snippets of folk songs, spirituals, poems, and the like. The text itself is filled with rhythm, repetition, poetry, and, even hand-drawn sheet music.

Intent:

I intended to explore the musicality in Ulysses, particularly Christian hymns and the “Sirens” episode, by means of recording, and preserving Hugh Sound’s Three Choruses Upon researching Three Choruses, I’ve only stumbled upon evidence of a single recording of this particular piece in spite of him being a notable composer through a tweet by BBC Three that links to a dead webpage. I intended to record the piece using my voice in tandem with the processing effects on my digital audio workstation, as it is not a long piece nor (seemingly) outside my ability, meaning I will use the advent of technology to ensure tonal accuracy. If we’re in the game of preservation, perhaps I’ll be able to further preserve the “Sirens” song from Three Choruses.

As I attempted to rearrange the Wood piece on the program MuseScore (a digital scoring program) for reference, I realized there is validity in the piece being unrecorded. While not impossible to perform, it is arduous beyond reason to be sung by one voice, even with the software at my disposal, it is unfathomably atonal and beyond my singing ability to break out of hard-wired western sensibilities of tonality. Later, I will discuss the form in detail to support the difficulties that arose. I think Wood may have made this piece as intentionally difficult to perform as “wink wink nudge nudge” to the scholarly unpacking of “Sirens” and the rage-inducing inscrutable Modernism of Ulysses. I promise, one day, I will be the one who records this piece and will request to update my Omeka exhibition upon doing so, but in the time span provided, the limitations of my vocal and arrangement abilities, and my hobbyist ideology (it should be fun!) regarding the fine arts, it will remain unrecorded for the time being. If Weezer had happened to have some unrecorded sheet music for a sunny alt-rock ode to “Penelope” kicking around the Special Collections, I would have no issues, but this is beyond my depth. However, thanks to some deranged pondering on “Sirens”, the Wood piece, Joyce, my own musical knowledge, and Joycian scholarship, I found connections between Ulysses and more contemporary ideas of music. I thought the epic ‘operatic’ nature of Ulysses lent itself more to classical conceptions, but uncovered that contemporary avant-garde and succeeding experimental music superimposed themselves quite nicely on the novel quite gracefully.

Literature Review:

Bowen, Z. R. (1974). Musical allusions in the works of James Joyce: early poetry through Ulysses ([1st ed.]). State University of New York Press.

Bowen provides justification for Joyce’s use of musical motifs and allusions in Ulysses. While much discourse on the “Sirens” episode centers around whether or not it is a Fuga per Canonem, Bowen not only refutes Levin’s article but shows how music and musical allusions enrich the characters and deepen Joyce’s use of “prosodic devices” (47). Cross-referencing Wood’s lyrics with their origins in “Sirens” in Bowen’s book help delineate the creative choices in “Op. 7”

Brown, Susan Sutliff. “The Mystery of the ‘Fuga per Canonem’ Solved.” European Joyce Studies, vol. 22, 2013, pp. 173–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871357. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

Brown claims to have solved the Fuga per Canonem mystery in his article with eight Italian words found in an early manuscript of Ulysses. Brown’s article is loaded with hyperbolic language and inflated conjecture, such as the ardent assertion that “Sirens changed literature forever”, which gives the article a tone of zealous enthusiasm but also an air of baselessness. Joyce’s conception of a Fuga per Canonem comes from Brown’s deduction that Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians was a definitive reference for “Sirens”, in which Joyce confuses the Fugue with the Fuga per Canonem. Brown asserts that Fuga per Canonem of “Sirens” is, in actuality, a “musically inaccurate but impressionistic invention abstracted from the [Grove] source”. By thoughtfully framing “Sirens” as an unruly impressionistic play on the fugue, Brown opens up the discourse beyond classical compositional forms I can thus utilize contemporary ideas as they appear in Wood’s composition without ignoring the scholarly discourse surrounding the Fuga per Canonem.

Levin, Lawrence L. “The Sirens Episode as Music: Joyce’s Experiment in Prose Polyphony.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 3, no. 1, 1965, pp. 12–24. JSTOR,

Levin locates the specifics of Joyce’s literary reappropriation of musical compositional techniques in “Sirens”. “Prose polyphony'' is operationally defined and identified in “Sirens”’ as a set of musical motifs including a prelude, rather than an overture, elements of fugal and canonical styles, and the obscure sixteenth-century “Fuga per Canonem” (13). Lawrence provides ruminative musical parallels in “Sirens” through its use of “word repetition, syllable repetition, alliteration, assonance” and the likes, but dubiously finds himself stuck to Joyce’s murky authorial intent to compose a textual Fuga per Canonem; an utterly indeterminable and obscure compositional style in which Joyce misattributed characteristics to according to Levin, is the backbone of the article’s argument. Levin’s article shows a thorough understanding of classic musical form and provides a useful framework for addressing the contemporary-classical content of Wood’s piece.

Sternfeld, F. W.. “Poetry and Music: Joyce's Ulysses”. English Institute Essays 1956. 1957. 16–54. Retrieved from https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.7312/frye92892-004/pdf

Sternfeld examines the entirety of Ulysses, rather than focusing solely on“Sirens”. “Poetry and Music” looks at Shakespeare’s use of musical motifs in Hamlet, much referenced in Ulysses, and Mozart’s epic opera Don Giovanni as through-threads of Ulysses through sylaballic patterns, or “prose polyphony” (Levin) by Joyce. Sternfeld suggests that Joyce’s is a harrowing example of “[modernist societies] rediscover[y] [of] Mozart and re-evaluat[ion] [of] the humor of Shakespeare, [...] [as] react[ion] [...] against the aesthetics of the Victorians.” (54). In essence, Sternfeld believes Ulyless exhibits a congruent rigid structure and playful experimentality much akin to the works of Mozart and Shakespeare. I feel Sternfeld articulately and substantively connects the taut form with experimental content that fuels speculation, inquiry, and passion for seemingly ‘difficult’ music and literature such as Ulysses, Shakespeare, and the undermentioned Ornette Coleman.

Zimmerman, Nadya. “Musical Form as Narrator: The Fugue of the Sirens in James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 26, no. 1, 2002, pp. 108–18. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3831654. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

Zimmerman acknowledges the futility of scholars' “formula for translating a musical written language” (109). Instead, Zimmerman asks a broader question, one disconcerted with authorial intent and the Fuga per Canonem: how does music function as the narrative voice in “Sirens”? If I were to flip Zimmerman’s thesis to address how Hugh Wood uses Joyce’s literary voice within music, and use their analysis to address how the text informs the music, I could bring the piece, “Sirens”, and the whole of Ulysses into their unified context: unseemingly rigid form begetting playful experimental content.

Final Arguement

Hugh Wood’s “Op. 7 No. 2” piece, acts as an ode to Ulysses’s “Sirens”. The piece is fugal, but it is not categorically a singular style of composition nor explicitly the much debated “Fuga per Canonem” (Brown). I propose “Sirens” does not fit squarely into the classical notions proposed by scholars, but something more akin to music beyond the scope of the early 20th-century genre. “Sirens” epitomizes Pound’s modernist mantra to “Make It New” (Bloudsoue) by not only weaving elements of antiquated music but by later predicting styles of music and sound art.

Wood’s work is described as “generally approachable” on his uncited Spotify biography but defies this in an effective Joyceian tribute with “Op. 7”’s “dissonant harmonies, [...] intricate textures,[...] rapid changes of mood and sonority” (Venn 98), and no discernible key nor key signature. In Ulysses, “Bronze” (Joyce 210) serves as a repeated term, no dissimilar to the imitated phrases in a fugue in a myriad of figurative connotations: Miss Douce (211), liquor (221), and Blaze’s shoe (217) for example, but it is in this untempered sea of associations that the assonance of bronze along with “gold” (210) become musical. Joyce repeatedly implores the emphatic operatic “O!” (214) in tandem with innumerable assonating “O” (215) words. One could assert the recurrent “O” alludes to Bloom’s uneasiness regarding Molly’s impending affair, perhaps O (215) for orgasm and “O!” (214) for orgasmic exclamation, it renders “Sirens'' syllabic and further from explicit meanings thus more song-like. Joyce implores an excess of O’s to emphasize Bloom’s voyeuristic orgasm in the later “Nausicaa” episode as well. When singing a fermata, one cannot form most cosanats while keeping their mouth open; they are limited to mostly vowels. This notion of vowels as the carrier of pitch serves the Wood piece as an effective way to transfigure the textual musical sensibilities of “Sirens” into a piece of acapella experimental music.

All of the lyrics in “Op. 7” derive from the opening “overture” or “prelude” of “Sirens”, including bronze and gold most notably, except for “still hearts of their each his remembered lives. Good, good to hear: sorrow from them each seemed to from both depart when first they heard” (Joyce 225). The melody set to Bloom’s rumination devolves the piece from an avant-tinged chamber piece into a disjointed hymnal drinking song. Conspicuously, the “still hearts” (Joyce 225) passage is four times intertextually removed before arriving at Wood: Saint-Georges’s text is the source for von Flowtow’s Martha opera (Kobbe), which was then translated into English loosely by Joyce for Simon Dedalus to sing, meditated on by Bloom amongst the noise of the Ormond bar, then in turn incorporated into “Op. 7”. The reduction of “Sirens” to a debate over authorial intent and the “Fuga per Canonem” does a disservice to its endless music allusions and unyielding experimentality. Wood’s piece recalls motifs of the canon, the fugue, and the folk song while not being singularly one of them, instead a piece of wholly modern music, much like “Sirens” and Ulysses altogether. I see closer parallels between Ornette Coleman’s 1959 The Shape of Jazz to Come to Wood and Joyce’s musical work in that both “Op. 7” and “Sirens” introduce musical themes, rather than rigid melodies, phrases, and tonal structures. “Sirens”, “Op. 7” and Coleman are bound only to a chordless melody, being the opening text of “Sirens” in the case of Joyce, that serve as a reference point rather than a rigid compositional structure. Freely incorporated and distorted musical ideas find cohesion inside a thoughtful labyrinthine structure in spite of their cacophony. Coleman’s “freely accented individual phrases and [...] adroit use of implied double-time” (Lonely Women 456) are more akin to the textual musicality of “Sirens” than the classical motifs suggested by scholars. The relentless use of authorial intent in “Sirens'' scholarship surrounding its musical categorization is made moot by the very same source letter that drives the “Fuga per Canonem” (Brown) debate in which Joyce admits to weaponizing “all the technical resources of music” (Millian 188). In terms of Wood’s authorial intent, he was notably open-mindedly surrounding popular music including a “passion [...] for Jazz” (Venn 183) while retaining a proclivity for “experiments in texture” (91). The playfulness exerted by Joyce in “Sirens” can not be superimposed one-to-one onto a singular compositional technique but is better understood by means of the contemporary classical ode as Wood has done, or perhaps, by looking to music made in the years succeeding Ulysses that reflect literary Modernist ideals like The Shape of Jazz to Come.