Nicolle Garnet (Editions)

Rationale

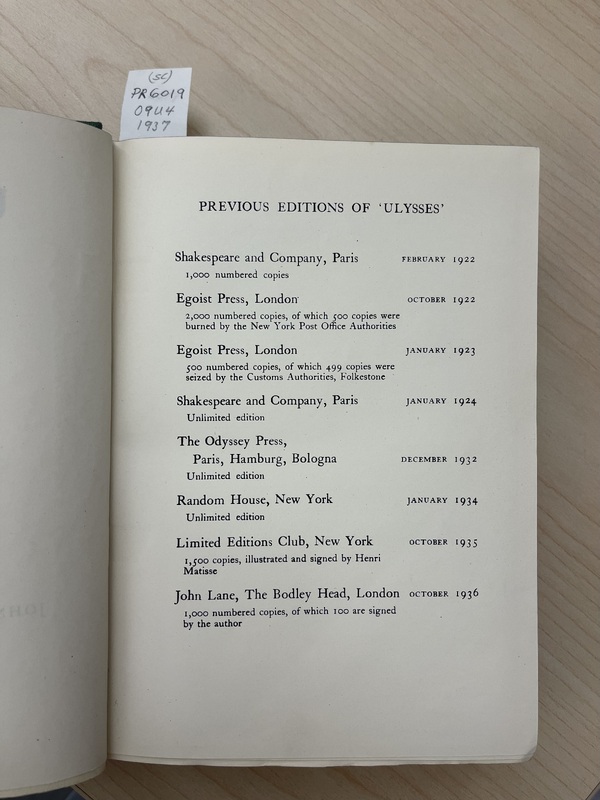

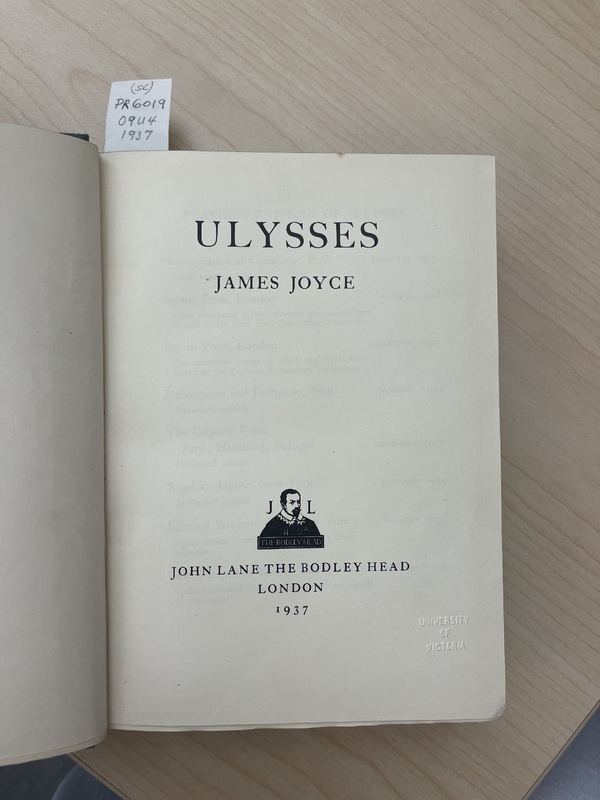

The Bodley Head edition of Ulysses by James Joyce was the first edition of his text to be legitimately published and circulated in the United Kingdom. It was not until the fall of 1937 that this trade edition was legally published in the U.K.; thus, this edition of Joyce’s text represents a shift in the politics and history of his book after its original publication in 1922.

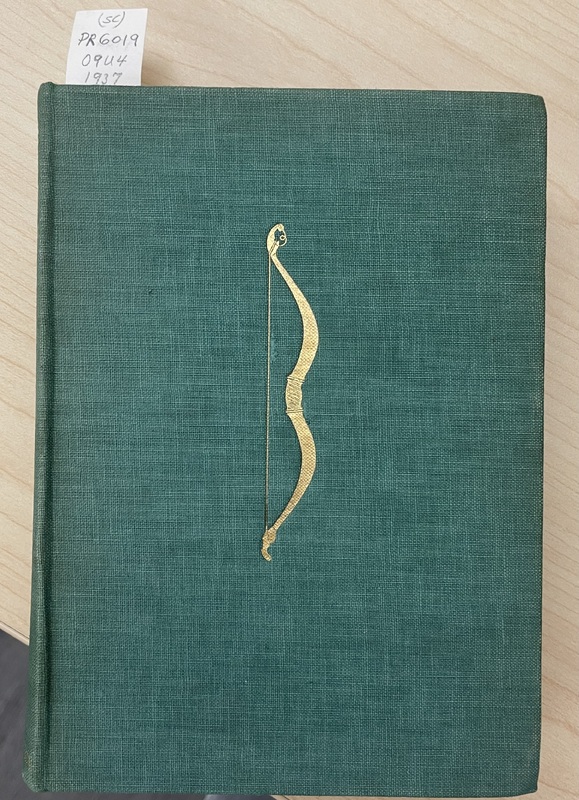

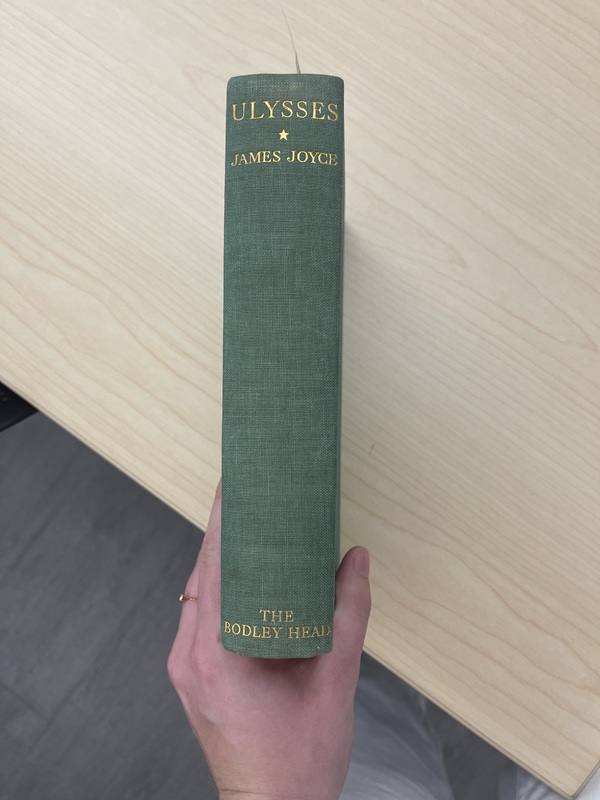

The Bodley Head edition was printed in London by Henderson and Spalding LTD in 1937, over a decade after it was originally released in Paris. This edition of Ulysses is a large-sized hardcover book, with a thick, rounded spine that still holds the novel intact. The paper used for title page and end papers are thick and opaque; thus, these pages inside the book are sturdy and creaseless. The rest of the pages in the book are quite thin and delicate, which allows light to shine through between the text. The font, however, is a stark contrast against the transparent pages, and is still as dark and black as I would assume it would have been when opening it for the first time. The hardcover of this edition does not feature a dust jacket; instead, it is made out of a steamed cloth, stretched over cardboard. The cloth's mossy-green colour has been worn in some spots, and the embroidery of the title, author and publisher on the spine of the book is a shiny gold. The front of the book features an image of a bow, also embroidered in the same gold colour as the text. After considering Ulysses as this physical object, it is interesting to infer whether Joyce would have been satisfied with this material design of his text; furthermore, would he have been given any input on the design or was he more concerned with the publication of his book in the U.K. after the countless political barricades he faced.

I selected The Bodley Head edition of Ulysses as my object because of its key historical significance in the circulation and censorship of the text as a full work. Joyce’s book was banned in the U.K. due to political reasons; thus, issues surrounding the reputation, censorship, influence, and corruption it could cause were the main concerns that initiated the prosecution of it. I am particularly intrigued by the political aspect of banning Ulysses, and how that was viewed historically. Moreover, I am also interested in the history behind why after banning it for over a decade, this specific trade edition got published without any prosecution. The 1933 decision of Judge John M. Woolsey would have had a huge impact on the publication of this edition, after a motion was filed to dismiss allegations that Ulysses was obscene under the Tariff Act of 1930. Woolsey authored to regard Ulysses as a classic and wholly outside of any construction of obscenity, so it was in that manner that he read the book in its entirety and declared it was not a book of obscenity. His careful assessment of the book revealed that the decision to deem Joyce’s novel legally obscene was made by governing bodies that merely reviewed isolated portions of the text considered wholly apart from the literary merit of Ulysses; thus, his rule was transformative for the reputation of Ulysses, and it is likely that this also helped the politics behind publishing it after Woolsey’s ruling. These are all aspects of my object that I want to discover, explore, and expand on to really grasp how the politics of this book affected its historical significance in 1937, as well now in the twenty-first century.

In my research, I expect that my findings will relate to the politics of publishing and marketing a book of obscenity. Furthermore, I expect that my research will contribute to the importance of my object, and display why this specific edition of Ulysses is so much more than just an additional version of Joyce’s work.

Literature Review

When considering the marketing and publishing of Ulysses, the reasons behind why it was censored and prohibited in the twentieth century is an extremely relevant part of its history. Joyce’s text was characterized as ‘obscene’ and ‘indecent’, and faced numerous political attempts to ban it from reaching the public. After reviewing the following research surrounding these conversations, I have begun to understand the literary politics that Joyce faced in order to circulate his text as a whole.

Katherine Mullin explores the censorship that Ulysses faced in relation to its identity in her chapter “English Vice and Irish Vigilance: The Nationality of Obscenity in Ulysses”. Mullin builds on “Joyce’s depiction of the genre of obscenity,” and the interpretations that Joyce’s text has been associated with in relation to indecent and smutty publications (73). She argues that other interpretations of Joyce’s work, specifically ones that refer to it as pornographic or vulgar, jump too quickly to see the text as a threat to national identity (Mullin 69). I am interested in the conversation that Mullin is involved in; thus, I am intrigued by her expansion on the definition of ‘obscenity’ and how it can be characterized in Ulysses based on the information you choose to put forward. Mullin’s argument also ties into the politics surrounding the censorship of Joyce’s text, and she begins to break down the interpretations that deemed it as a pernicious piece of literature.

Alistair McCleery’s article, “A Hero’s Homecoming: Ulysses in Britain, 1921-37,” examines the political aspects of publishing Ulysses, and references specifically the 1937 Bodley Head trade edition that I have chosen as my object. Two common themes arise in this article that are apparent in Mullin’s work: obscenity and censorship. McCleery examines the publishing history of Ulysses, as well as the representation of the text in different parts of the world and how that affected the marketing of the print as a whole (67). I would like to ground my research in this aspect of Joyce’s text; thus, the political and marketing barriers that had to be crossed to even allow Ulysses to be published despite its indecent reputation amongst the United Kingdom.

Another contributor to the conversation surrounding the marketing of Ulysses is Kevin J.H. Dettmar. Outlined in his article “Selling Ulysses,” Dettmar nuances the publisher’s involvement in marketing Joyce’s text and the marketing attempts by Joyce himself (795). He argues that “Joyce’s anxious efforts to market Ulysses … were not at all anomalous, but rather symptomatic of the complex and often contradictory attitude the modernists held toward advertising, [and] marketing…” (Dettmar 796). This stance that Dettmar offers is much different than the other arguments I came across in my research, and I am intrigued by this articles examination of Joyce’s involvement in creating momentum for Ulysses; moreover, Dettmar’s differing perspective allows for a more rounded analysis of the politics surrounding the marketing and publishing history of Ulysses.

The last two journal articles I found in my research focused directly on the censorship and banning of ‘obscene’ literature in publishing; thus, I want to build on the nuances of censorship and obscenity, and marketing and politics that come up in the history of Ulysses publication. The first article I will reference, “Banned Books and Publishers’ Ploys,” was written by Alistair McCleery who I referenced previously for her article on the edition I have chosen as my object. McCleery highlights a common connection between other authors books condemned as obscene, such as Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928) and D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928); thus, the challenges that the representations of these books possessed when trying to publish and market them to the world. The other article that related to this argument was Maurice Couturier’s “Censorship and the Authorial Figure in Ulysses and Lolita”. Couturier's article specifically stood out to me because of the comparison between Joyce’s work and the work of ladimir Nabokov; further, the representation of the Olympia Press edition of Lolita and the Bodley Head trade edition of Ulysses share similar design features that hold them to being considered obscene and indecent. The Olympia Press had a reputation for the Travellers Companions Collection that were identified as mossy green-coloured novels that were often smutty or of an erotic nature; thus, the Bodley Head trade edition of Ulysses is physically represented in the same way as the Olympia Press collection. I want to enter this conversation surrounding how that would have and did affect the marketing and publishing challenges that were already so present in the politics of the content of Joyce’s work.

Short Paper

The Category of Obscenity: Smutty Intertexts in Ulysses

The conversation surrounding the obscenity of James Joyce’s Ulysses is endless, and the censorship of the novel in countries across the world stands for the political aspects of publishing literature during the early twentieth century. After being banned for over a decade, the publication of the 1937 Bodley Head trade edition of Ulysses would have come as a surprise to many in the U.K., including Joyce one would assume; further, this edition represents a book that was bound with the assumption that it would be circulated for a very long time, and its seemingly plain exterior contrasts greatly from what is inside. In considering the politics of publishing a book of ‘indecency’, themes of marketing and the reception of smutty romance novels run throughout the text, and home on the connection between the 1937 trade edition and my approach.

The first reference to indecency within literature in Joyce’s text appears during “Calypso”, when Molly complains that “there is no smut” in Ruby: the Pride of the Ring (4.355). Molly’s disappointment in the book Bloom has gotten for her engages with the connection the text has to the clear misinterpretation of Joyce’s text as an obscene piece of literature. Bloom’s stream of consciousness passes on the illustrations of Molly’s book, “Fierce Italian with carriagewhip. Must be Ruby pride of the on the floor naked”, and suggests that they were what got his attention when choosing the book for her (4.346-47). Joyce’s intertext reference is based on an actual book by Amye Reade, which depicted the illustration that Bloom thinks about. Just as Bloom mistakes the illustrations on the novel as ‘smutty’ by the depiction of a nude body within a novel, Joyce’s text was considered indecent by the unease of defining the genre of ‘obscenity’ in literature. Consequently, Molly and Bloom’s misinterpretation of the intertext engages with the politics of publishing Ulysses in the United Kingdom. The Bodley Head trade edition was designed to disguise the unease that surrounded Joyce’s novel, and it is arguable that the only reason the 1937 edition avoided prosecution was because of this strategic marketing tactic.

Other intertexts of Ulysses that draw on the genre of obscenity are mentioned in “Wandering rocks,” when Bloom “turned over idly pages of The Awful Disclossures of Maria Monk, then of Aristotle’s Masterpiece” in the bookshop (10.584-5). Joyce’s reference to these two texts is deliberate, as they fall under the resisting classification of obscenity in literature; moreover, the reputation of these texts engage with the reputation of Ulysses, and the act of classifying vice from virtue that Joyce was drawing attention to. As for the connection to the Bodley Head trade edition, the classical Odyssean bow on the front of the cover and the slightly hidden “Ulysses” title on the spine of the book were deliberate marketing choices made by the publisher. This edition presents itself as a modest novel, and it would have been easy to hide the identity of the book from the eye of others considering the reputation Joyce’s novel had conjured up across the publishing world.

In considering the relationship between my approach, object and the text of Ulysses itself, the censorship of the Joyce’s novel derives straight from the politics surrounding marketing and publishing during the early twentieth century. The connection between Joyce’s texts as a physical object and the intertexts as representations of the borderline dividing morality and obscenity insist that the Bodley Head trade edition had to overcome the political limitations of publishing an already disreputable text. With this, the parallels of the text and my research reveal the fascination Joyce had regarding the categorization of ‘obscenity’ in literature, and how the political nature of publishing and marketing required finding ways to physically present it in a contrasting way.

Works Cited

Couturier, Maurice. “Censorship and the Authorial Figure in Ulysses and Lolita.” Cycnos, vol. 12.2, 1995. Nabokov: At the Crossroads of Modernism and Postmodernism. epi-revel.univ-cotedazur.fr/publication/item/425. Accessed 8 Nov. 2022.

Dettmar, Kevin J. H. “Selling ‘Ulysses.’”James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 30/31, 1993, pp. 795–812. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25515769. Accessed 8 Nov. 2022.

Gibson, Andrew, et al. “English Vice and Irish Vigilance: The Nationality of Obscenity in Ulysses.” Joyce, Ireland, Britain, University Press of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 2006, pp. 68–82.

McCleery, Alistair. "'A Hero's Homecoming': "Ulysses" in Britain, 1922-37." Publishing History, vol. 46, 1999, pp. 67. ProQuest, http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/scholarly-journals/heros-homecoming-ulysses-britain-1922-37/docview/1297997011/se-2. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.

McCleery, Alistair. “Banned Books and Publishers’ Ploys: The Well of Loneliness as Exemplar.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 43, no. 1, 2019, pp. 34–52. EBSCOhost, https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/10.2979/jmodelite.43.1.03. Accessed 3 Nov. 2022.