Dr. Patricia Köster, Ulysses, and Female Scholarship

Zoe Salvin

"Thumbed pages: read and read. Who has passed here before me?" (Joyce 199)

Introduction

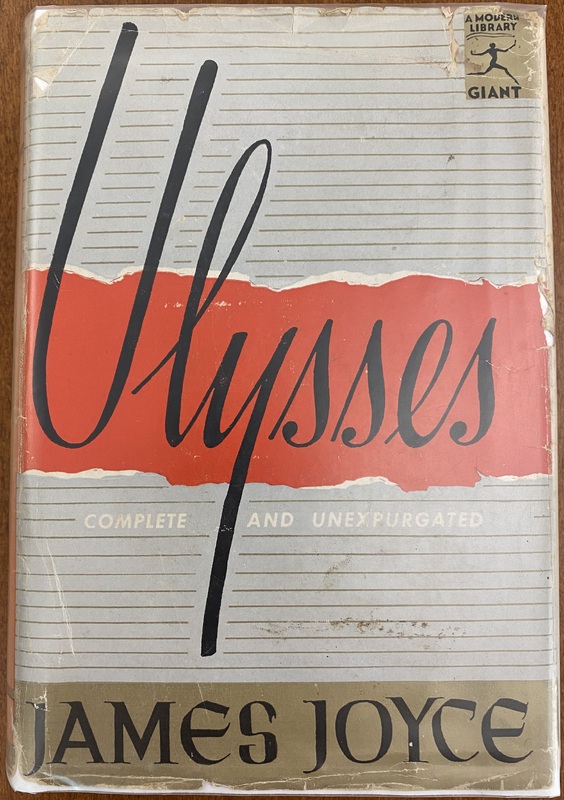

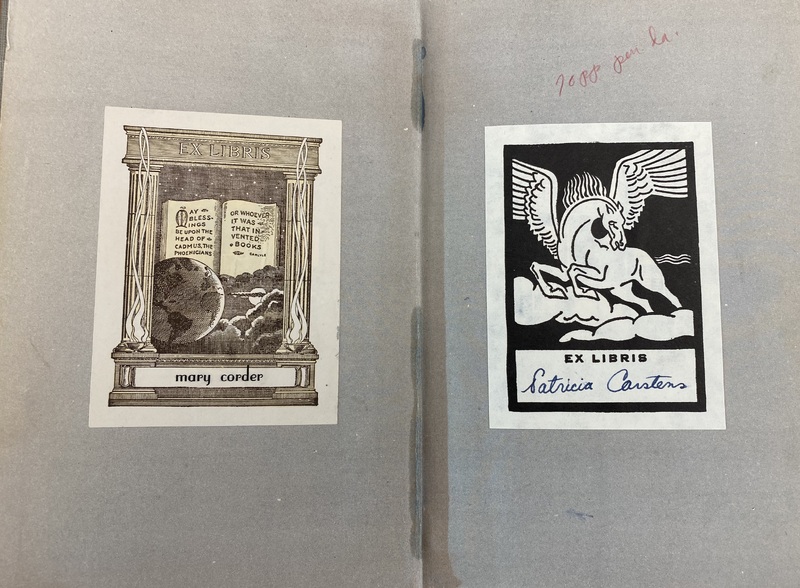

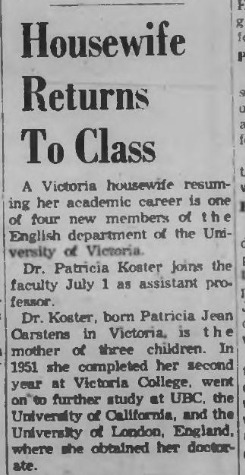

The object I have chosen to study is a hardcover copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses published in 1946 by The Modern Library as part of their “Giant” collection. Inside the front cover are two Ex Libris labels indicating at least two previous owners; their names are Mary Corder and Patricia Carstens. On the next page there is a University of Victoria label attributing the item as having come from the library of Dr. Patricia Köster. Further research revealed that Patricia Köster was born Patricia Jean Carstens in Victoria, indicating that she owned this copy of Ulysses prior to her marriage to Karl Köster in 1958.

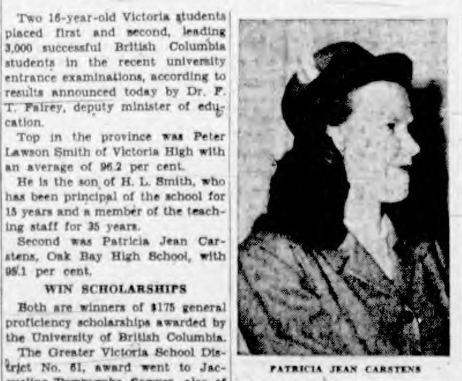

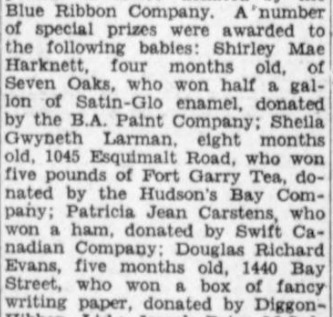

A Victoria local, Dr. Köster was a founding member of the UVic English department. Before pursuing her Honours B.A. at UBC, her M.A. at the University of California, and her Ph.D. at the University of London, she had demonstrated remarkable academic prowess by having the second highest university entrance exam result in British Columbia in 1949. In fact, she was already winning awards as a baby, having won the special prize of a ham in Victoria’s popular “baby show” in 1933.

Her academic career at UVic lasted from 1958 until 1995, and she donated over a thousand volumes of books to UVic’s special collections. The volume I studied is one of them, but for a deeper look into her donations, you can read more from Dr. Janelle Jenstad, one of the co-curators of a 2012 exhibit honouring Dr. Köster’s donations.

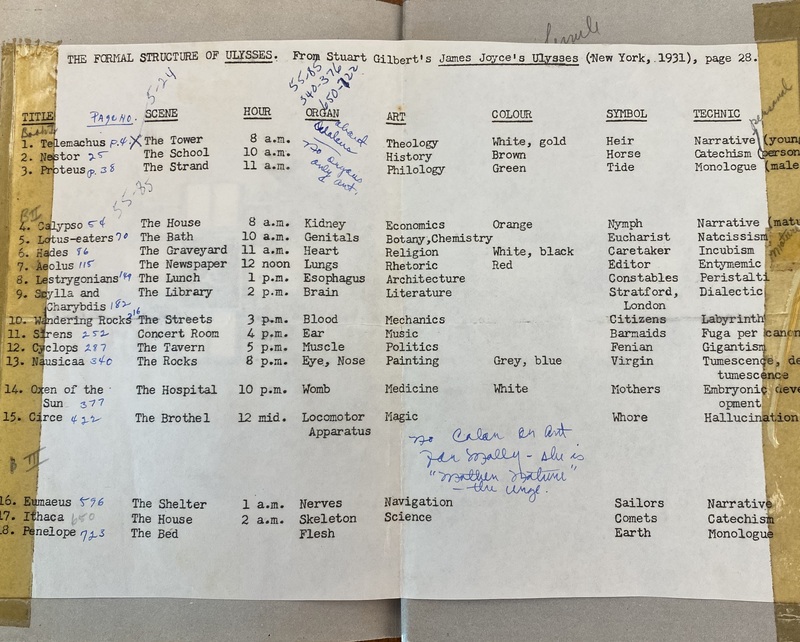

This copy contains a foreword by Morris L. Ernst and the court decision of Judge Woolsey. Taped inside the back cover of the book is a typewritten copy of the Gilbert schema (citation included), with handwritten notes in at least three different shades of blue ink as well as pencil, suggesting at least four sessions of annotating. There are also margin notes throughout the text. I am no handwriting analyst, but the handwriting appears to be Dr. Köster’s, as there is a very distinct swoop on her capital Cs that is consistent from the Ex Libris label to some of the annotations on the schema. Some of the annotations in the margins and underlined text may be Mary Corder’s contribution, but as there is no indication of whose hand the annotations came from, I will be treating all annotations as coming from Dr. Köster.

I selected this object because I was intrigued by the signs of ownership and use that are throughout the book. There are at least two women who have previously owned the book and have gone to the effort of staking a claim through the use of Ex Libris nameplates. As well, Dr. Köster had a very in-depth reading experience with the book, as evidenced by the Gilbert schema and the annotations (unsurprisingly, as we know that she was a passionate reader and scholar). I find the readers to be the most interesting part of a book’s history, because readers can have incredibly varied backgrounds and points of view and they often leave evidence behind of their unique experiences within the pages of the book itself.

I hoped to discover some insight into what it was like to read Ulysses in the 1940s and 50s. I also hoped to discover more about Dr. Köster, or at least deduce some information about her and her thoughts about the novel through her annotations. As well, I wanted to investigate the aspect of being a female reader of Ulysses in the 1940s, and how the lens of gender may have influenced their readings of the text.

Literature Review

Because my object contains Judge Woolsey’s decision before the novel itself, I wanted to look into the response of early readers to the decision as paratext. Robert Spoo discusses this in “Judge Woolsey’s Ulysses Opinion: Early Print History and Reader Response.” Spoo’s article claims the effect of reading the decision as two-fold; would-be censors are discouraged from pursuing a case that has been effectively closed, and everyone else is given a preparatory overview of the content they are about to read, creating a sense of “informed consumption” for readers otherwise unfamiliar with the novel (Spoo 62).

The other name written in the book was Mary Corder, and as I have not yet found any record of her attached to any university, I am assuming she was more along the lines of the “common reader” Robert Alter discusses in “Joyce’s Ulysses and the Common Reader.” Alter argues against the idea that only students and professors like Dr. Köster are capable of enjoying Ulysses, and that all a reader needs to tackle Ulysses is patience, “a knowledge of English… and a little imagination” (Alter 24).

The women that owned the copy of Ulysses I’m studying were among the earliest contributors to a community of readers, but I also wanted to research the experiences of the readers that followed them. Frances Devlin-Glass’ “Who ‘Curls Up’ with ‘Ulysses’? A Study of Non-Conscripted Readers of Joyce” summarizes the results of surveying Bloomsday participants in Melbourne. The article includes not only data on age and education, but also information on what the respondents feel is difficult or satisfying about Joyce’s work, and other questions about why they read Joyce.

I want to expand on the findings of this survey, and note similarities and differences between the data and Dr. Köster. These early 2000s readers mostly aged over 40, with 89% of the men and 97% of the women being of this age group (Devlin-Glass 365). Dr. Köster came into possession of Ulysses at least before she was 25, and was therefore quite a young reader compared to the survey respondents, though many of the respondents had been reading Joyce for at least twenty years (Devlin-Glass 368). An “overwhelming majority” of Joyce readers had at least one post-secondary degree, and 41% had a second (Devlin-Glass 367). Many readers indicated that they had “cheerfully embarked in a long journey of understanding” with Ulysses (Devlin-Glass 368). This is a sentiment Dr. Köster evidently shared; she acquired the book prior to her marriage in 1958, and it remained in her possession until her death in 1996.

Though Ryan K. Guth’s “Experiencing Technical Difficulties: A Reader’s Negotiation with the Compositional Method of ‘Ulysses’, Episode 12” is specifically discussing only one episode of the novel, Guth does explore how the experience of reading Ulysses may be different if the reader has access to supplemental material such as the Gilbert schema to aid in their comprehension of the novel. This applies to my object specifically because there is a copy of the Gilbert schema taped in the back, indicating that at least one of the book’s previous owners made use of academic writing such as the schema while reading Ulysses.

To more broadly explore the effect of Gilbert’s criticism on reading Ulysses, I found Lee Spink’s book, James Joyce: A Critical Guide, to be helpful. Spink discusses a variety of critical responses to Joyce, but I am mainly interested in the discussion of Gilbert’s work. Spink argues that because Gilbert was writing his criticism in a time when Ulysses was still facing censorship challenges, he was in fact providing many readers with their “first acquaintance” with the novel (Spink 168).

So What?

Through exploring readership of Ulysses, I have noticed that despite Joyce scholarship appearing at first glance to be quite male-dominated (as many fields of academia appear to be), there is an overwhelming amount of female Joyce scholars, and female readers of Ulysses. I have concluded that a large part of the female reader’s draw to Ulysses is the respect with which Joyce writes his women as not only people, but as readers to be respected in their own rights. By writing women with respect, Joyce has created a community in which women like Dr. Köster feel comfortable diving into academic readership of his work.

The first example of a female reader we encounter is Molly Bloom. Upon waking, she asks her husband to help her find a book that she had been up reading the night before. Immediately, the act of reading late at night suggests to the audience that Molly is an avid reader. She has encountered a word in this novel (Ruby: the Pride of the Ring, which is based on a novel about exploitation in 19th-century circus troops) that she is unfamiliar with, and wants to ask Bloom about it. Joyce is demonstrating that Molly is not only an avid reader, but an active one. She asks Bloom about the word “metempsychosis,” and she receives a technical answer: “It’s Greek… the transmigration of souls.” She asks for the definition “in plain words,” but with a “mocking” look in her eyes noted by the narrator (Joyce 52). The mocking look suggests that Joyce’s narrator knows that Molly is capable of comprehending Bloom’s definition, but that she is poking fun at his formal way of explaining it.

Despite Joyce writing Molly as an intelligent reader, Bloom does not share this opinion of his wife. He opines about Molly’s “deficient mental development” in episode seventeen and disparages the fact that she sometimes uses “digital aid” when calculating, or that she interprets strange words phonetically (both normal things for even intelligent people to do) (Joyce 562). Despite Bloom’s insulting thoughts about his wife, it is clear that Joyce has written her as an intelligent person, and that the reader is not meant to take Bloom’s opinion of her as fact.

The other major example of a female reader is Dilly Dedalus. Stephen encounters her at a book cart after she has purchased a French primer. Stephen does not have as disparaging a view of female intellect, yet he still instinctively considers his sister reading as a surprise. He tells himself to “show no surprise” at her attempt to educate herself, yet he feels despair at the thought that his sister’s intellect is “drowning” in poverty, which indicates that both Stephen and Joyce recognize her intelligence (Joyce 200).

Beyond recognizing women as intelligent readers, another draw is his portrayal of Molly in the final episode. Molly’s stream of consciousness was revolutionary, and Joyce did not shy away from detailing her bodily functions, her sexual fantasies, her innermost thoughts, and her power over the men around her. As a modern female reader, I felt like Joyce had captured female thought and personality in a way that very few male writers have managed to do. I can only imagine this sense of kinship and of being seen was even stronger to readers who had even fewer examples of well-written women to look to.

Female readers like Dr. Köster are drawn to Joyce because he acknowledges women as intelligent readers, and this has led to the Joyce community being made up of more women like than many realize.

Annotations

Finally, I want to highlight some of the annotations in Dr. Köster’s book, as I feel they are the most accurate representation of her reading experience. I cannot speak about them all, as there are many, but I’ve selected a few.

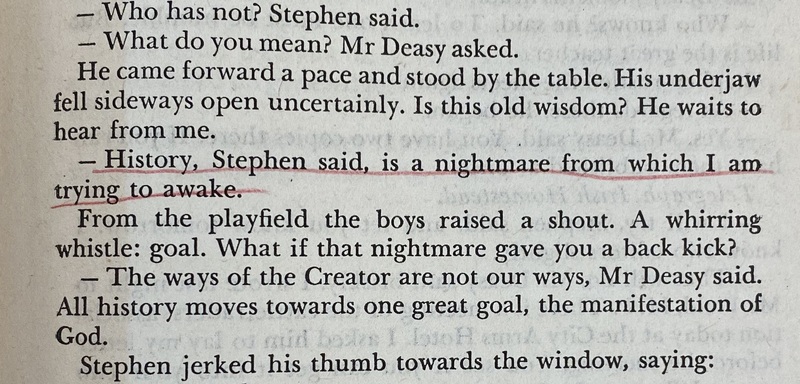

First, Dr. Köster has underlined the line: "History, Stephen said, is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake". This line is one of the most famous from Ulysses, and Dr. Köster clearly agreed. There are no notes, perhaps indicating that the line needs no further commentary.

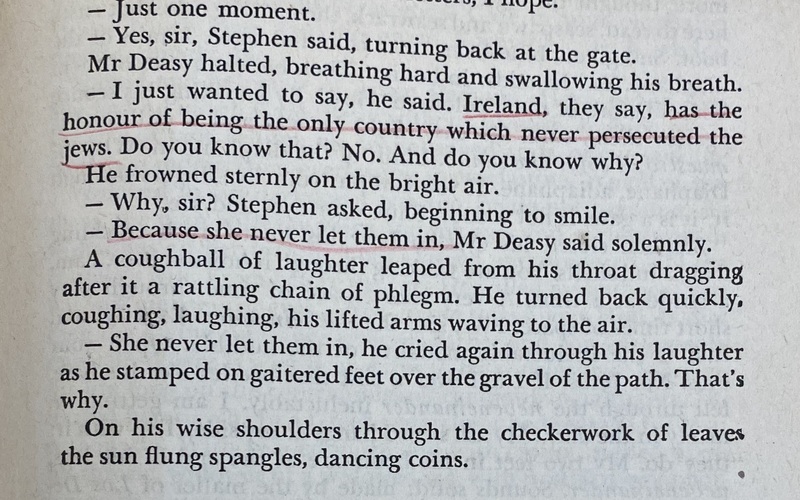

Another line that is underlined is the joke Deasy makes about Ireland having never let Jewish people in, and therefore never having persecuted them. Again, Dr. Köster has left no additional notes in the margins. This annotation possibly highlights the joke itself, possibly the anti-Semitism, or possibly the factual inaccuracy of Ireland never having let Jewish people within its borders.

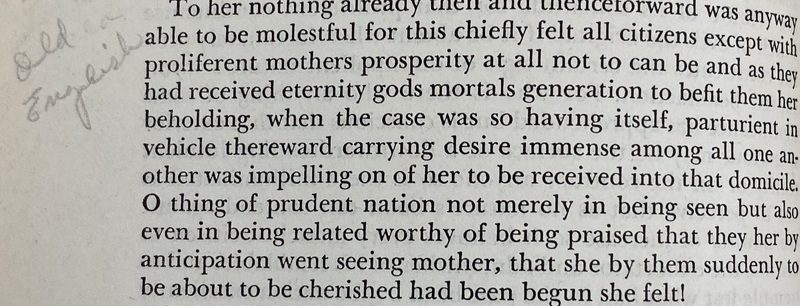

I have included two annotations from the episode “Oxen of the Sun”; there were many, as Dr. Köster indicated in the margins whenever the prose switched from one era of English writing to another. The two images here are where she indicated the Old English and Chaucer sections began. The many annotations throughout this chapter suggest that Dr. Köster was familiar with the various styles of writing, and that she was actively reading the chapter to identify when these styles switched.

I have also included images of some annotations that do not have an apparent meaning, in the hopes that someone else researching this object may be able to connect some dots. There is a list of numbers on the last page, which do not correspond to the page numbers of the chapters, or the annotations. There is also a list of words written on the end paper beneath the Gilbert schema: ferrule (?), metres, monice (?), maladial (?), and diaphane, along with the number 138.

Finally, there is a typewritten copy of the Gilbert schema taped in the back of the book. There are numerous annotations including page numbers for all the episodes in her edition, suggesting that this was a well-used resource in Dr. Köster's study of Ulysses. This is also the source of the capital C that led me to believe that these annotations are Dr. Köster's. At the bottom of the schema, she has written "no color or art for Molly - she is 'Mother Nature'" and the handwriting closely matches that on her Ex Libris nameplate.

Works Cited

Alter, Robert. “Joyce’s Ulysses and the Common Reader.” Modernism/modernity 5, no. 3 (1998): 19-31. doi:10.1353/mod.1998.0048.

Devlin-Glass, Frances. “Who ‘Curls Up’ with ‘Ulysses’? A Study of Non-Conscripted Readers of Joyce.” James Joyce Quarterly 41, no. 3 (2004): 363-380. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25478065.

Guth, Ryan K. “Experiencing Technical Difficulties: A Reader’s Negotiation with the Compositional Method of ‘Ulysses’, Episode 12.” James Joyce Quarterly 40, no. 4 (2003): 753-762. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25477992.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Suffolk: Penguin Random House UK, 2022.

Spinks, Lee. James Joyce: A Critical Guide. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

Spoo, Robert. “Judge Woolsey’s Ulysses Opinion: Early Print History and Reader Response.” Journal of Modern Literature 43, no. 1 (2019): 53-70. muse.jhu.edu/article/745757.