Jackson Campbell (Little Magazines)

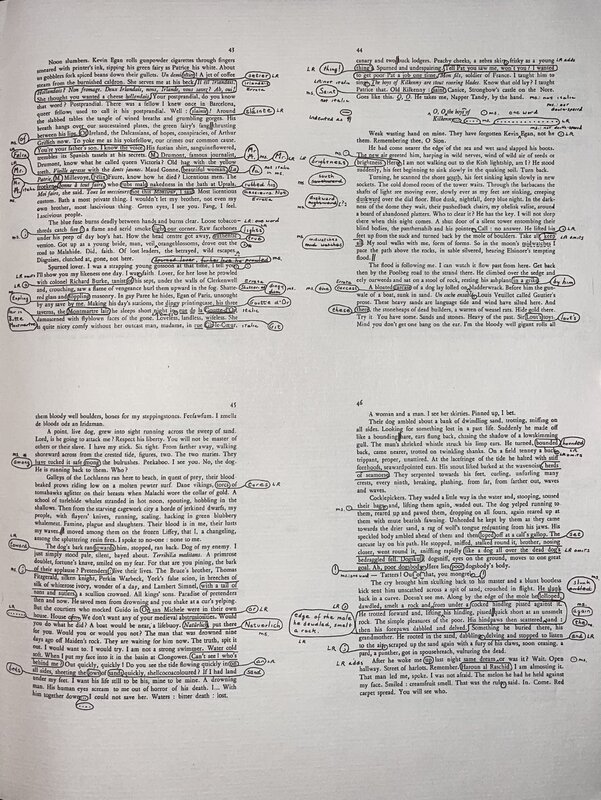

The object that I have chosen in order to delve deeper in James Joyce’s Ulysses is a facsimile of Joyce’s original manuscript of the novel. In the facsimile there is the full, final copy of the book with annotations filling each page in the margins. Each annotation is marked with one of two abbreviations: LR or M with LR being edits that the serial production in The Little Review made, and M being what the original manuscript had written down. In a brief and skimming look through, a vast majority of these annotations are minor adjustments: capitalization, basic grammar, spellings. However, there are some changes that come across with greater significance, including and not limited to, additional sentences, the swapping of various words, and some more significant grammar alterations.

This facsimile is by no means light. It does, of course, contain the entirety of Ulysses, but has the additional marginal annotations. With all this extra information added into the already dense book, there is copious amounts of potential for research into understanding Ulysses. What I would like to do, specifically, is to look through the facsimile and find a particular chapter of Ulysses that has more changes than others and figure out why there were more changes from the original manuscript to the final published version. I believe that the most interesting parts of the facsimile will be analyzing what The Little Review added in their publications, as it was the first publicly available version of Ulysses. Seeing what the public would have initially read, and subsequently banned from sale, will ideally provide insight into the decision to ban the novel from shelves. Though using an analysis focused around ‘why was this changed?’ could prove interesting, there is little in the way of proof when it comes to answering that question. Without the ability to actually question James Joyce himself, and thus gain an understanding of why he chose the words he did. Instead, it makes a great deal more sense to look at how the changes made in the printed manuscript as well as in The Little Review and analyze how it altered any potential analysis and understanding of the book.

My personal goal in studying the facsimile will be to compare the final, published copy, to the altered version in The Little Review and the manuscript. I will be selecting one or two chapters from Ulysses, and doing an in depth reading of both the changed version and the original. It is entirely possible that some of the changes will not entirely change one’s understanding of the text, but there are a significant amount of changes that are made within each chapter that may warrant deeper research.

I selected this object because of the amount of changes that I noticed when I first opened the book. Seeing this amount of changes, regardless of significance, made me realize the sheer amount of changes that were made by the time the version we read today.

Given that the object that has been chosen for a delve into James Joyce’s Ulysses is a facsimile of the original manuscript, with the edits handwritten, it makes sense to review what others have done regarding the use of language in the book. Take, for example, Paige Miller’s article titled “Translanguaging Joyce: Monolingual Disruptions and Translingual Enrichment in Ulysses.” Miller discusses how Joyce’s characters will often slip across a plain of translingualism; the utilization of words or phrases that have meaning across multiple languages. She brings up how Molly, in Ulysses, was brought up in British-occupied Gibraltar, where Spanish would have been one of the languages spoken. In citing ‘Penelope’, Miller brings up where Molly opts to use the Spanish word ‘embarazada’, as opposed to its English counterpart of ‘pregnant’. While I, personally, do not see a lot of value in the analysis of multilingualism in Ulysses, it does not take away from its prevalence in looking at Joyce’s likely deliberation over the language to use. This deliberation becomes even more evident when one reads Maria Kager’s article, entitled ““Bilingual Obscenities: James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Linguistics of Taboo Words.” Kager begins the article citing a letter from Joyce to Nora Barnacle in 1909, where he writes about how she has never heard Joyce utter an unfit word in the public sphere. Why then is the language of Ulysses so over the top explicit, to the point of being obscene by law? This is a conversation that I consider immensely valuable in the analysis of language, especially in looking at what The Little Review altered by way of language choice. This will absolutely be a source that is built on in my analyses. Natasha Chenier does something that initially comes across as a bizarre comparison when she compares Ulysses to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in her article “‘And Words. They Are Not in My Dictionary’: A Lexicographical Study of James Joyce and the Oxford English Dictionary.” Chenier discusses how the mission of the OED is to set the precedent for morally acceptable lexis, whereas Joyce strived to challenge the norm of language and redesign how it was communicated. The second publication of the OED featured 1800 citations from Joyce, and the third featured over 2400. An interesting point Chenier makes here is that, of those 2400 citations in OED 3, many of them are not cross-referenceable with OED 2. As such, this article revolves heavily around the comparison of ‘traditional’ language usage in everyday life, and pits it against the ‘unconventional’ language that Joyce employs in his text and thus will be utilized to continue the conversation about the changed language from the manuscript into the published versions. For the published versions, we turn to George Monteiro and his compilation of reviews on James Joyce, not specifically Ulysses, in the United States between 1916 and 1920. The reviews cover a variety of Joyce’s publications, and also present a variety of opinions. As such, it is not necessarily something that can be argued against given that it is a statement of opinion from a variety of sources. Though it will be interesting in providing insight in the public attitude towards Joyce in this time period, its contribution towards the analysis of the facsimile is likely minimal. Perhaps the most interesting literary article comes from Paul Sopčák, where he studies what is now the third chapter of Ulysses from a rough draft discovered in 2002. Sopčák looks over the changes that were made from draft to manuscript, and how previous studies would still hold up with this newfound information. It should be clear that this is a key article that will be of significant use in the argument of how the changes may change understanding of Ulysses. As this research has progressed, the decision was eventually made to analyze the third chapter of Ulysses: 'Proteus'. As such, Sopčák's article is of essential importance in this analysis, and will be used to a significant degree in furthering the research done.

Following an abundance of research into the significance of some chapters within James Joyce’s Ulysses, the decision of which chapter to critically analyze with the facsimile of the manuscript landed on 'Proteus'. Though 'Circe' proved to be a potentially omission-heavy chapter due to The Little Review’s rather conservative expurgations, however The Little Review ceased publication of Ulysses after page 376; approximately half of 'Oxen of the Sun'. 'Proteus' is a difficult chapter within Ulysses, but remains incredibly important due to it being the first chapter where Joyce’s stream of consciousness is blatantly obvious. As such, the chapter also presents as a challenging checkpoint for readers of Ulysses, and proves to be a place in which many throw in the towel on completing the book. Prior to diving into the omissions made by The Little Review, one must first understand the importance of analyzing these omissions. Why should they matter? Put simply, looking at what is omitted from such a significant piece of literature can determine what other sources deemed inconsequential to the understanding of the piece. However, as this essay will explore, there remains a number of pieces within the chapter of 'Proteus' (and more than likely many other chapters within Ulysses) that add some contextualized depth to the book and to the reader's understanding.

A delve into the facsimile shows that there are several omissions made by The Little Review, one most notably coming on page 43: “You’re your father’s son. I know the voice.” Given that a lot of the omissions that were made by The Little Review were done so to prevent the spread of overtly sexual and graphic within Ulysses, this line feels particularly innocent to omit. It is a line that also adds some deeper context to the previous one: “To yoke me as his yokefellow, our crimes our common cause.” A yokefellow, in this case, is referring to someone who is a husband or wife; someone that will be sharing the burden of life with you. The line omitted, the one regarding your father’s son, does not necessarily fit with the definition of a yokefellow as a husband or wife, but nonetheless is appropriate when talking about someone sharing life with you. The following line states “His fustian shirt, sanguineflowered, trembles its Spanish tassels at his secrets.” This line seems to fit with the overall theme in 'Proteus': Stephen walking on a beach contemplating a variety of philosophical ideas, and included among these thoughts (within the same paragraph) is him knowing fellows in Barcelona and Ireland. Hence, the aforementioned Spanish tassels do fit in context with this fellow from Barcelona.

Another rather significant omission comes a few pages following, and is a short paragraph describing, in rather vivid detail, a dog urinating on a rock. Modern day literature obviously does not view such a description as particularly explicit, but for the time of Ulysses’ publication, this omission makes a lot more sense than the line about the father’s son. What The Little Review does do, in this instance, is replace the description of urinating with a short piece about the dog instead dawdling near the rock, and smelling it. This is a regular activity for a dog, and would thus not be given a second look by any person who read the book. However, within the omitted paragraph is a line that has some weight: “The simple pleasures of the poor.” This description, slotted into a descriptor of a dog urinating on a rock in public, shows almost this societal apathy that poor people would have to view public urination as a simple pleasure. Granted, it is unpleasant the amount of descriptors Joyce has used, and thus makes sense as to its omission in The Little Review. However, this line that is included in said omission does take away from what seems like would be a crucial understanding in the text.