Luca Nemet (Little Magazines)

Project Rationale

I have selected as my object the first issue of Blast (1914), the quintessential magazine of the Vorticist art and literary movement in Britain. Short-lived yet massively influential, Blast was thought of by American critic Ezra Pound as a “great MAGENTA cover’d opusculus” [capitals in original] (Lewis and Pound 138). Pound then described it to James Joyce as “a new Futurist, Cubist, Imagist Quarterly [...] it is mostly a painters' magazine with [Pound] to do the poems” (Pound 26). I am specifically interested in exploring constructions and representations of masculinity in Blast, such as the idealization of war and the parallels drawn between men and machines. I am also eager to examine the publication’s interrelated rejections of Romanticism and femininity. For this project, I will endeavour to demonstrate how Leopold Bloom’s characterization as ‘the new womanly man’ defied traditional gender roles and accompanying connotations. To do so, I will illuminate the stark contrast between Bloom’s femininity and the hypermasculinity presented in Blast, which aligns closely with heteronormative societal gender norms of the time period.

Bloom is often described by Joyceans as an ‘androgynous’ character; viewed simultaneously as possessing traits of both genders as well as being separated and exiled from them. There have also been several claims of Bloom being effeminate, though throughout the novel Bloom’s sexuality towards women is depicted brazenly and with a distinct unabashedness. Throughout Ulysses, Bloom finds himself often ostracized by his male peers and is depicted with a sense of sympathy unusual for a male protagonist in this time period. I have chosen Blast because of how the publication depicts masculinity and what ideas and qualities its contributors associate with men. In Blast, the Vorticists idealize hypermasculinity and violence, values which Bloom clearly does not embody, while also devaluing the feminine qualities that are central to Bloom’s character. Moreover, I believe that Blast is well-suited for comparison to Ulysses because it includes works by James Joyce’s contemporaries—most famously, the aforementioned Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis—providing valuable insight into select prominent competing perspectives on masculinity of the era.

I am seeking to expand on existing research about masculinity in Ulysses and to illustrate how uniquely Joyce’s writing of Bloom subverts traditional—and, as evidenced by Blast, modernist—conceptions of gender. To my knowledge, there is no existing scholarly analysis of Bloom’s unconventional ‘feminine manliness’ that centres around an analysis of and comparison to Blast magazine. As such, my interpretations and arguments will be completely original, though informed by relevant research. Consequently, I will contribute an entirely new perspective on masculinity in Ulysses, an exciting accomplishment considering the wealth of research on the novel’s main themes.

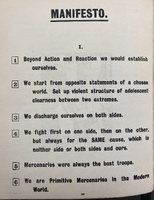

In order to truly engage with Blast, I will need to analyze the art, poetry, and prose the publication offers, especially the Vorticist Manifesto written by Wyndham Lewis. This will require analyzing not only the content itself but its historical and social context. Furthermore, because my object must remain in the Special Collections reading room, I will need to find access to my object online. Unofficially uploaded versions online are subject to be taken down due to copyright infringement, so I will ensure that I locate my object from multiple online sources to reduce the risk of losing access. As a final precautionary measure I will take pictures in addition to those I upload while I am in Special Collections to guarantee my access to important passages.

Review of Relevant Literature

I intend to examine how James Joyce’s Ulysses subverts traditional and modernist ideas of masculinity and femininity, especially as they are embodied in the character of Leopold Bloom. To accomplish this, I will compare and contrast the novel with Vorticist magazine Blast, another modernist publication which clashes with Ulysses not just stylistically, but morally and politically. In addition to research on gender in Ulysses, literature concerning the gendered aesthetics, origins, and politics of Vorticism is relevant to my work.

Principally important to my argument is the Vorticist rejection of femininity and its embrace of a masculine artistic vision. As Oliver argues in her discussion of how artist Marianne Moore was influenced by the movement’s “modernist abstraction,” Vorticist aesthetics were distinctly and essentially masculine (85). Likewise, Hickman dissects Vorticist imagery and form, demonstrating how the movement employed geometric patterns in response to the ‘feminine’ artistic traditions characteristic of Aestheticism. She argues that the clean lines and sharp angles of Vorticist art were “a part of Vorticism’s phobic response to ‘effeminacy’” (Hickman, preface). As Hertz explains, this Vorticist anti-effeminate sentiment exemplifies a “familiar paradigm of Modernism,” wherein creating ‘good’ art necessarily involves rejecting femininity (356). Concentrating on the political implications of stating that art cannot be good and feminine, Williams explores how the men of the Vorticist movement—feeling threatened by imagined consequences of women entering the public sphere and by the looming collapse of the British empire—championed masculinity not only to subvert the ‘feminine’ traditions of art movements past, but to “defeat the effeminate forces of degeneration and decline” (81). Joyce, on the other hand, chose to write an effeminate main character who supports his wife’s artistry; I argue that this suggests an intentional rebuttal against the comparably unfavourable Vorticist view of femininity.

An integral part of the Modernist movement was the ‘crisis of masculinity’ with which Vorticism and Futurism, a movement with very similar ideals and aesthetics as Vorticism, were both deeply concerned (Macedo). Macedo examines how Futurism devalues the feminine, not only by rejoicing in violence and a “‘brutal’ style of concrete, material imagery,” but by demeaning and objectifying women. She is especially interested in how the Futurist Manifesto (1909) and others like it reflect the societal discourse of the era on the topics of female sexuality and female emancipation; in particular, she argues that the Futurist movement’s proclaimed support for women’s rights is performative, “serv[ing] only instrumentally as a means to the thorough fulfilment of the male's needs and pleasure” (Macedo 248). As Hertz notes, the Vorticist Manifesto (contained within Blast, 1914) similarly mock-supports women’s rights in an address to suffragettes (358). Crucially, these observations illustrate that, at the time Joyce was writing Ulysses, the larger literary climate was one hostile to effeminacy.

As relevant literature has evidenced, the negative representations of femininity in Blast contrast sharply with those that I have identified in my reading of Ulysses, wherein the protagonist is written as effeminate and good-natured. My research will delve deeper into this apparent rejection of effeminacy and a simultaneous embrace of masculinity in Blast. I am particularly interested in expanding on the existing perspectives about which qualities the Vorticists link with which gender, and the connotations of these associations.

Blasting Bloom: Gendered Traits in Blast and Ulysses

In this paper, I will explore how Leopold Bloom challenges the modernist views on manhood presented in Blast, the artistic and literary magazine of the Vorticists. In Blast, modern Britain is condemned as a dull and uninspired society in need of an artistic revolution. The Vorticists want to disrupt the English tradition of sentimentalism, which they ‘blast’ as outdated and with which they associate effeminacy and femininity. Blast thus advocates for a violent revolt against this perceived ‘feminine’ stagnation to produce a new dominating aesthetic that is fundamentally masculine in its chaos, coldness, and hardness. As evidenced by his correspondence with Ezra Pound, Joyce was aware of Blast (Pound 26). Consequently, Bloom could be his response to the views on gender expressed within Blast—just as the character of Shaun in Finnegan’s Wake was Joyce’s response to harsh criticism of his writing by Wyndham Lewis, Blast’s editor and foremost contributor (Klein 2).

While Blast aims to “[s]et up [a] violent structure of adolescent clearness between two extremes” (Lewis 30), the ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine,’ Ulysses deconstructs gender and blurs its arbitrary boundaries through Bloom, who exhibits traditionally ‘feminine’ behaviour: in “Calypso,” he makes breakfast and runs errands for his wife, Molly; in “Aeolus,” he is patient and polite even when treated dismissively; and throughout the novel, he outwardly shows empathy, especially towards women and animals. In “Circe,” Bloom’s effeminacy is ‘diagnosed’; he is declared “bisexually abnormal” (Joyce 402, ll. 1775-6) and “a finished example of the new womanly man” (Joyce 403, ll. 1798-9). Bloom actively avoids conflict when possible, even when that means being talked over or otherwise disrespected. He is also a sentimental man, one who could be described as being ‘stuck in the past’ when he is not consumed with anxiety about the present—he is in near-constant emotional turmoil over his son’s death and Molly’s infidelity. This passiveness and sentimentality define Bloom as distinctly unmasculine in Blast’s terms.

As mentioned, Blast identifies sentimentality with women; men, contrarily, should be “CONCEIVING instead of merely observing and reflecting” [capitals in original] (Lewis 153). Bloom, however, ruminates often on his past, and feels particularly nostalgic for past experiences with Molly. In one such instance, he reminisces about a day ten years previous, when he and Molly went out together to a dinner and concert. He dwells on such details as Molly’s “elephantgrey dress with the braided frogs” which “fitted her like a glove” and how the “American soap [he] bought: elderflower” had made Milly’s bath smell nice; he thinks sadly that they were both “[h]appier then” (Joyce 127-8, ll. 158-74). This passage from “Lestyrgonians,” wherein Bloom is shown to be ‘craving’ and ‘hungering for’ his former contentment, shows a man clearly absorbed in his past. In examining Bloom’s flashback, I have shown that he cares deeply about and is wrapped up in the past, behaviour which Blast suggests that men, who must “stand for the Reality of the Present” (Lewis, foreword) should not exhibit.

Blast’s mission “to destroy politeness” (Lewis, foreword) and its celebration of violence can be easily contrasted with Bloom’s passive and conflict-avoidant nature. Bloom is perhaps best described as mild-mannered and soft-spoken. As Joyce writes of Bloom in “Oxen of the Sun,” wherein he is abstaining from the drunken rowdiness in which the medical students are engaging: “sir Leopold that was the goodliest guest that ever sat in scholars’ hall and that was the meekest man and the kindest” (Joyce 318, ll. 182-3). When sensitive topics are discussed insensitively by other men—as with suicide in Hades (Joyce 78, ll. 335-41) and multiculturalism in “Cyclops” (Joyce 266, ll. 1156-9)—Bloom goes quiet, uninterested in an argument. One rare occasion wherein he does speak up is after being told to “stand up to [injustice] with force like men” (Joyce 273, l. 1475), to which he responds that “force” and “hatred” are “not life for men and women” (Joyce 273, ll. 1481-2); here, his denouncement of violent revolt clearly contrasts with Blast’s praise of the same.

Bloom's dislike for confrontation is further exemplified in “Circe,” wherein he repeatedly attempts to de-escalate the conflict between Stephen and the privates Compton and Carr. Here, Bloom first tries “softly” explaining Stephen’s drunkenness and vouching for him: “He doesn’t know what he’s saying. Taken a little more than is good for him. Absinthe. Greeneyed monster. I know him. He’s a gentleman, a poet” (Joyce 483, ll. 4487-9). When this fails to defuse the situation, Bloom lies, telling the soldiers that he and Stephen were “Irish missile troops” who “fought for [Britain] in South Africa” and were “[h]onoured by [their] monarch” (Joyce 486, ll. 4607-8). Throughout the scene, Bloom urges Stephen to stand down but he, unlike Bloom, is not reluctant to fight, and does not heed his warnings. By examining these passages, I have shown how Bloom, rather than idealising violence as Blast implies a man should—and as other men in Ulysses do—prefers peaceful conflict resolution or else avoids confrontation altogether.

Despite Bloom’s effeminacy, he is the protagonist and we readers sympathise principally with his narrative. Other male characters in Ulysses, who embody Blast-esque masculinity in their shared penchant for violent discord, are shown to be rude and reckless. Through Bloom, Joyce thus opposes the prominent modernist view on gender espoused in Blast: he establishes a ‘womanly man’ who is passive and sentimental, not as a “dismal symbol” of decline (Lewis 11), but as the hero of his own story.

Works Cited

Hertz, Erich. “The Gender of Form and British Modernism: Rebecca West’s Vorticism and Blast.” Women’s Studies, vol. 45, no. 4, 2016, pp. 356–369. DOI: 10.1080/00497878.2016.1160751

Hickman, Miranda. The Geometry of Modernism: The Vorticist Idiom in Lewis, Pound, H.D., and Yeats. University of Texas Press, 2005. Google Books.

Joyce, James. Ulysses, edited by Hans Walter Gabler. 1986. Vintage Classics (Penguin Random House), 2022.

Klein, Scott Warren. Opposition and Representation: The Fictions of Wyndham Lewis and James Joyce. 1990. Yale University, PhD dissertation. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

Lewis, Wyndham. Blast, no. 1, 1914. Internet Archive.

Lewis, Wyndham, and Ezra Pound. Pound/Lewis: The Letters of Ezra Pound and Wyndham Lewis, edited by Timothy Materer, London: Faber, 1985. Internet Archive.

Macedo, Ana Gabriela. “Futurism/Vorticism: The Poetics of Language and the Politics of Women.” Women: A Cultural Review, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 243–252. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/09574049408578206.

Oliver, Elisabeth. “Redecorating Vorticism: Marianne Moore's ‘Ezra Pound’ and the Geometric Style.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 34, no. 4, 2011, pp. 84–113. DOI: https://doi.org/10.2979/jmodelite.34.4.84

Pound, Ezra. Pound/Joyce: The Letters of Ezra Pound to James Joyce, edited by Forrest Read, New York: New Directions, 1967. Internet Archive.

Williams, Georgina. “The Politics of Aesthetics and the Woman Question.” The Politics of Aesthetics of the Female Form, 1908–1918. Palgrave MacMillan, 2018, pp. 77–105. SpringerLink.