Mules Nicholas (Visuals)

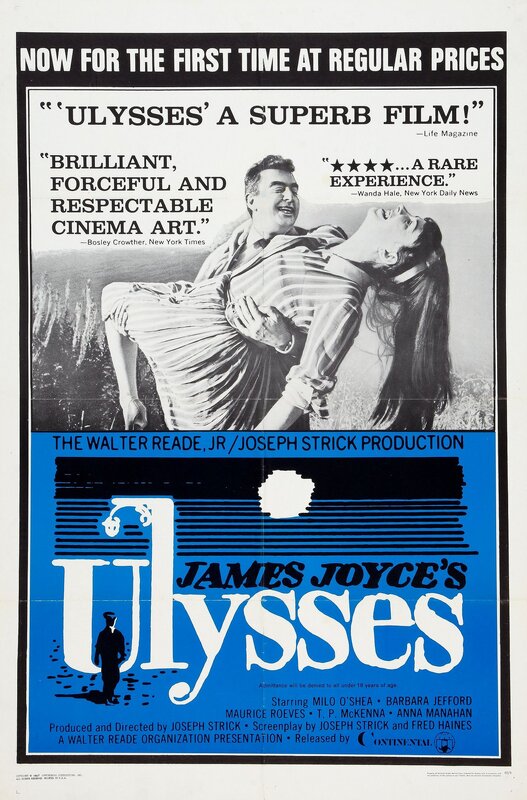

My choice of ‘object’ for this project is the 1967 film adaptation of ‘Ulysses’. The movie is directed and produced by Joseph Strick, with the screenplay written by Strick alongside Fred Haines. It starred Milo O’Shea as Leopold Bloom, Maurice Roëves as Steven Dedalus, and Barbara Jefford as Molly Bloom. It was released in March 1967 in the US, June 1967 in the UK.

I chose to examine this piece because I think it offers practically unlimited avenues for analysis and comparison to the original text. Originally, I specifically chose to seek out an adaptation of Ulysses because I wasn’t captivated by other objects, such as different editions or magazine printings. These items lend themselves well to topics like advertising, book history, editing, etc, but I wasn’t particularly interested in those more mechanical aspects of Ulysses. I was more interested in the content of the narrative, the characters, events, and themes Joyce explores, and it was easy to see how I could tie these concepts to my object. What did Strick focus on? What did he cut? What did he choose to add, or change? How might these differences and similarities between the adaptation and the source material reflect cultural attitudes towards the subject matter in 1967 as opposed to when Joyce published the book? I originally planned to focus on this difference in the attitudes of Joyce and Strick towards the audience’s expectations, specifically in how the works approach sex and masculinity. As I learned more, however, I found ways to link the medium of movies specifically to the style of Ulysses, and from there to its themes and impact.

Film is a significant lens through which to approach a study of Ulysses, as Joyce himself was a huge fan of early cinema. He went so far as to open the first cinema in Dublin! Examining the connections between Joyce and film even helped me properly understand how a physical object might be related to the content of the book, even though I originally chose the film so that I could compare content to content; I came to realize that Joyce’s enthusiasm for cinema is visible in his work. Joyce drew on popular cinematic techniques of his time, and translated them into writing techniques. That got my gears turning, and eventually led me to my final research questions: How does Joseph Strick’s film adaptation of Ulysses recreate Joyce’s style, especially the cinematic techniques found within the novel itself, and to what end are such devices used?

With these questions in mind I dove into the literature surrounding James Joyce’s relationship to film, as well as the scholarship around Strick’s adaptation. I found research on the latter to be disappointingly sparse, but I did find some important background information on the film in the article ‘Updating “Ulysses”: Joseph Strick’s 1967 Film’ by Margot Norris. Although the content of the movie is lifted almost entirely straight out of the book, the two works taken as a whole stress significantly different themes. The largest of these changes is the lack of emphasis on the issue of Irish national identity, and their conflict with the British, in Strick’s version. Norris outlines a few reasons that this integral piece of Ulysses thematic tapestry was largely ignored in the film. Many of these reasons are simply practical. Adapting any novel large as Ulysses to the screen will require cutting significant chunks out, but why choose to drop the focus on Irish nationhood? Norris offers the explanation that to an audience in 1967, the issue wasn’t particularly relevant. Ireland had been recognized as an independent republic for decades, and it was a relatively peaceful time in their history. This also relates to another practical reason for the change, as to save money Strick changed the setting of his Ulysses to Ireland in the 60s. Thus Irish nationhood was a distant memory both for his audience, and for the setting of his movie, and so he chose to devote more screen time to other themes from Ulysses. Norris points specifically to discussion of antisemitism, which remained a more hot button issue in Strick’s time.

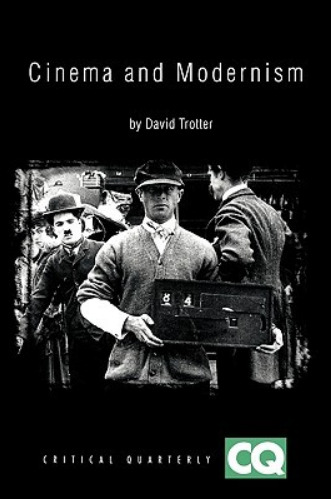

But how are these themes represented through style, and how do these styles and techniques differ between book and film? ‘Bringing Bloom to the Screeen: Challenges and Possibilities of Adapting James Joyce’s “Ulysses' ' is an article by Maximilian Feldner that lays out some of the reasons Ulysses is widely considered difficult to adapt to a visual medium. He focuses on Joyce’s use of interior monologue, stream of consciousness, internal perspective, and stylistic experimentation, each of which is complicated to recreate in a visual medium. He gives some examples of how Strick addresses these aspects of Ulysses in his film, or minimalizes them . He also laments that some portions of Ulysses which aren’t included in the movie lend themselves to adaptation, as Joyce uses ‘cinematic’ writing devices. These devices are critically important to my question, and addressed directly by David Trotter in his book ‘Cinema and Modernism’, which devotes an entire chapter to cinematic techniques used by James Joyce. This book was very helpful as it laid out some of the connotations and associations of these techniques when they were employed in film. Later we’ll examine how Joyce played with these techniques by recreating their original effects or satirizing them in Ulysses. Eric Meljac’s article “James Joyce, the Cinematic Modernist” points out additional instances in Ulysses of the cinematic techniques explained by Trotter.

Interestingly, there is also an almost meta conversation being had around how Joyce invokes cinema in his work. His writing can recreate not only the mechanical tools filmmakers would use in creating their art, but the experience of sitting in a theatre and viewing it. Philip Sicker, writer of the article “Alone in the Hiding Twilight: Bloom’s Cinematic Gaze in “Nausicaa”” argues that this episode in particular casts Bloom as the movie-goer observing Gerty’s show. He purports that in cinema and pornography the female body is relegated to the role of an object to be observed by the male gaze, and that Joyce recreates this dynamic through his language, allusions, and style in the ‘Nausica’ episode. It’s interesting that reference to early film can be seen in this chapter, and obviously the encounter with Gerty is part of the larger theme of sex in Ulysses. I think there is a conversation to be had about the portrayal of this scene in the movie, in which the focus remains on Bloom’s upper body during his voyeurism and his masturbation is left more ambiguous than the book. Is the sexual theme being downplayed, or merely presented differently in the style of the film?

Some of these articles outline stylistic difficulties in adapting Ulysses to screen. Others, the practical limitations of Strick’s production. I think there’s an interesting discussion on their differences impacting themes in their works, and the intersections found in episodes such as ‘Nausicaa’. The reduction of Irish importance is logical, but some sexual scenes were also dialed back. How many changes made were practical versus intentional tightening of narrative/themes? Where might there be missed opportunities in Strick’s film? These are all interesting topics, but to focus my contribution I’d like to draw together the conversations of where Joyce’s and Strick’s styles overlap or differ, specifically in Joyce’s use of cinematic techniques. Trotter’s book is the cornerstone of this discussion, but we disagree on the effect of Joyce’s use of them. Also, there are stylistic elements and tools deployed in Strick’s movie that are unique to the visual medium.

So, how does Joseph Strick’s film adaptation of Ulysses recreate Joyce’s style, especially the cinematic techniques found within the novel itself, and to what end are such devices used? To tackle the first part of this question first, we’ve already mentioned the stylistic obstacles laid out in Feldner’s article. As a most basic example, Ulysses is prone to using vast swathes of internal monologue. In episodes like “Telemachus” and “Penelope” this monologue makes up the vast bulk of the content, and thus Strick has to recreate their substance using techniques that are possible in a visual medium. In these cases he simply chooses to have the characters narrate their thoughts over top of the footage. Narration is a bit taboo in filmmaking and generally used as sparingly as possible, and so the extent to which Strick uses it in his film is indicative of the importance of the internal lives of the characters. Narration is also one of the only ways to portray the stream of consciousness style of Ulysses, without which it seems Strick thinks it wouldn’t be itself. In this case a film tool is used to approximate the style and substance of a literary one, but in other instances the conversion is much smoother.

Now we return to Trotter’s work, and my disagreement with some of the conclusions he arrives at while discussing cinematic devices in Ulysses. One example of Joyce’s cinematic stylings, explained by David Trotter in Cinema and Film, is the intercut. Intercutting is simply cutting back and forth between two or more scenes happening at the same time. This creates a montage. Joyce makes extensive use of this technique in the episode “Wandering Rocks”, which shows us glimpses into the lives of many people going about their day in Dublin. The meat of the chapter is riddled with textbook examples of intercuts, both within and between paragraphs. But how does this stylistic choice interact with the content and themes of the novel? Joyce liked films, and he incorporated their style into his work. So what? Well, by examining intercuts in “Wandering Rocks” and understanding how they’re used in film we can extract meaning from the novel. One common and early use of intercuts was to showcase economic disparity, intercutting between the destitute and the wealthy. We can see this trope in the cut between the crippled sailor begging for coins (Joyce, 185), to the Dedalus household (Joyce, 186). They may also be in poverty, but they have a home, and books to sell, and friends who give them food. Then we cut at once to Blazes Boylan (Joyce, 187), who checks a ‘gold watch’. After describing the intercut, Trotter says that the evidence for the montage effect in Joyce’s writing is weak. He says there’s no evidence of Joyce using intercuts the way they were used in cinema, specifically to build suspense or establish socio-economic disparity (Trotter, 90). The latter point I flatly disagree with, as I believe the piece of montage above illustrates the levels of poverty/wealth quite effectively. As far as establishing suspense, I would argue that in the case of Ulysses the intercut is used to parody such suspenseful tropes.

This subversive example of intercutting also hinges on Boylan. In “Wandering Rocks” he’s buying fruit to send to Molly, and flirting with the young vendor. This scene is intercut with Bloom browsing the bookstore, also on the hunt for a gift for Molly. This cut reminds us of Bloom’s devotion to Molly, as well as reminding us of her infidelity. With Trotter’s explanation of the ‘race to the rescue’ trope, which was a common effect of intercutting in films, we can take this analysis a step further. The race to the rescue montage cuts between a vulnerable maiden, someone trying to reach her with ill-intent, and her gallant love interest rushing to the rescue. The intercuts create tension by showing both parties rushing towards the girl (Trotter, 89). The Odyssey could arguably be described as one long race to the rescue scenario as well, with Odysseus rushing home to save Penelope from the advances of her suitors. In Ulysses, neither man rushes. Trotter says this lack of urgency means Joyce must not be employing the intercut as seen in film, but I see it as a funny inversion. The fiendish character is subverted by Molly’s eagerness to have him, and the hero by his willingness to let it happen. This little parody is my favourite example of how understanding Joyce’s cinematic techniques, and the associations attached to them in film, provides a new perspective on the text.

Other intercuts require no background knowledge to deliver emotional and thematic resonance. Stephen’s encounter with his sister (Joyce, 200), and dilemma of whether to save himself or risk drowning with his family, is immediately intercut with Simon, who’s seemingly content to let his daughters rot. This manages to reinforce the tragedy of the Dedalus family, and ties Stephen’s conundrum back to the theme of paternity. This is an intercut that Strick recreated exactly in his film, and it’s another of my favourites. Strick also has some original uses of the intercut that further the themes he’s chosen to focus on. Haines voices his concerns to Stephen over the Jewish threat to Britain and Ireland, and even as his words continue the visual cuts to our introduction of Bloom, puttering around his kitchen in a frilly apron making breakfast for his wife and cat. The juxtaposition of the scenes make clear how ridiculous Haines’ bigotry is. Overall though, I’d have to agree with Feldner that Strick could have brought more cinematic moments from Ulysses to the screen. By being included in an adaptation to the medium from which they were originally drawn, they take on a new meta-textual layer of meaning for fans aware of Joyce’s fondness for cinematic devices. Other than that Strick did his best in an endeavour few thought possible, and brought Ulysses to the screen.

Bibliography

Trotter, David. “Chapter 4.” Cinema and Modernism, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2008, pp. 87–125.

Feldner, M. (2015). Bringing Bloom to the Screen: Challenges and Possibilities of Adapting James Joyce’s “Ulysses.” AAA: Arbeiten Aus Anglistik Und Amerikanistik, 40(1/2), 197–217. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24722046

Sicker, P. (1999). “Alone in the Hiding Twilight”: Bloom’s Cinematic Gaze in “Nausica.” James Joyce Quarterly, 36(4), 825–851. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25474089

Norris, M. (2003). Updating “Ulysses”: Joseph Strick’s 1967 Film. James Joyce Quarterly, 41(1/2), 79–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25478028

Meljac, E. P. (2009). James joyce, the cinematographic modernist. The Explicator, 67(4), 279-283. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/scholarly-journals/james-joyce-cinematographic-modernist/docview/578497628/se-2