ACTUAL TITLE: "Optics and Intellectualism in the Context of Ulysses" [idk if we're getting page titles or not but that's what I want mine to be if so :)]

Burd Kiarra (Visuals)

Introduction

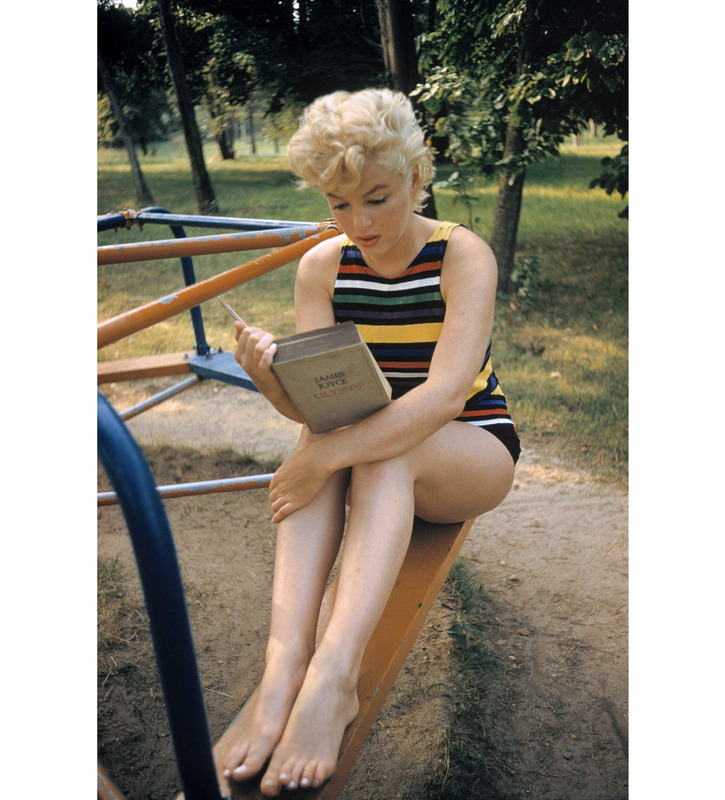

The 1934 American Random House edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses was the first non-serialised edition to be published in America after its initial publication in 1922, having been suppressed due to complaints against its obscene content (British Library). Notably, this edition appears in the 1955 photo taken by Eve Arnold of Marilyn Monroe reading at the park, her long, bare legs acting as a surface on which to rest the large tome (pictured above).

Although Monroe was an avid collector of books and was often photographed reading, her beauty and notoriety as the “ditzy blonde” caricature in classic Hollywood films spurred criticism about her ability to comprehend a book of such literary renown, with some sceptics even considering the photos as being a set-up (Conway). Moreover, an Open Culture article published in 2012 notes that “It’s still debated whether [her love of literature] was simply an attempt to recast her image … or whether she actually had a pensive side.” Due to the fact that her sex appeal appears to contradict with the analytical prowess associated with Ulysses, the idea of Marilyn reading the text is unbelievable to certain critics.

By exploring Arnold's photo of Monroe with the 1934 American publication of Ulysses, I hope to shed light on how the reception of this picture resembles the treatment of women in Joyce's epic with regards to sexuality, objectification, and intellectualism. While my approach will rest primarily on the portrayal of Molly Bloom and the "Penelope" chapter and academic articles associated with it, I will also interrogate other textual instances that depict the complicated relationship between womanhood and educational opportunity.

Overview

Similar to the public reception of Monroe, Ulysses often portrays women as sexualised objects with limited cognitive capacities, especially with regards to Molly Bloom. For example, the "Calypso" chapter contains a depiction of Molly from the perspective of her husband Leopold that emphasises the complex relationship between female allure and literariness: following the erotic tableau of Molly from the perspective of Leopold, she asks that he define the word “metempsychosis” (U 4.337-42). She then fails to understand his verbose definition, which highlights intellectual differences between her and her husband (U 4.344). Afterwards, she requests a book by “Paul de Kock” (U 4.358), a coy reference that reiterates the relationship between her sexuality and literary interests.

However, the final chapter "Penelope" gives insight into the swiftness of the female mind by shifting to Molly’s voice in first-person narrative, which complicates Leopold’s image of her as relatively unintelligent. Though not endowed with the learnedness of her husband, her comment that “he says your soul you have no soul inside only grey matter because he doesnt know what it is to have one” (U 18.141-43) indicates that she contemplates similarly existential problems as him regardless of her inability to communicate them in intellectual terms. In fact, Molly sees Leopold’s academic perspective as negatively affecting his understanding of the world since “he never can explain a thing simply the way a body can understand” (U 18.566-67) and “he wont let you enjoy anything naturally” (U 18.1191). To Molly, her womanly experience is a source of cognitive strength and her ignorance allows her to contemplate the world in a more intuitive way than that of scholarly men: in her words, “[she] wouldn’t give a snap of [her] two fingers for all their learning” (U 18.1564-65).

Molly also derides Bloom's intellectualism when compared to Stephen Dedalus, becoming fixated on him in the "Penelope" chapter because she expresses a deep desire "to have a long talk with an intelligent welleducated person” (U 18.1493-94). Since Bloom fails to share her artistic sensibilities and reprimands her (often erroneously) for her lack of education, she considers his opinions unreliable (U 18.1187-92). Instead, she daydreams about Stephen living in their house, since he is considered artistic and might actually understand her (U 18.1478). Though she eroticises his intellectualism in a similar manner as Bloom does to scholarly women (U 8.133-34; 13.1087-88) when she states that "[she] wouldnt mind taking [Stephen] in [her] mouth" because "[she's] sure itll be grand if [she] can only get in with a handsome young poet at [her] age" (U 18.1349-59), her attraction to Stephen aims to fill the cerebral void produced by Leopold's unwillingness to appreciate her perspective rather than resembling Bloom’s fetishistic objectification.

Critical Perspectives

Critics have often written about how male scholasticism provides an integral lens with which to view James Joyce’s Ulysses; however, the status of female intellectualism receives much less coverage. While some critics unite Ulysses with the socio-historical problem of female education in 19th-century Ireland (see Creasy), most scholars approach this topic through the character Molly Bloom, often with special focus on her unpunctuated 1609-line monologue in the “Penelope” episode. The critical articles by Schwaber, Creasy, O’Brien, and van Boheemen provide useful paradigms for dissecting characters in Ulysses who are intellectually separate due to their womanhood. Since there is a notable lack of critical analysis about other women in this novel, this overview will focus on articles that investigate Molly Bloom.

Molly is often situated as the dissatisfied and adulterous wife of Leopold Bloom who exists as a sexual and romantic object endowed with “natural” womanhood based upon spontaneity and emotionality rather than academic learning, and many attempts to untangle the vast monologue in “Penelope” have resulted in reductive or problematic gender essentialist claims about her. Whether or not Joyce intended Molly to be interpreted “as emblem of the eternal feminine,” as van Boheemen suggests (72), Paul Schwaber rejects the idea of Molly as a non-intelligent figure, since “She lacks education but has a cunning intelligence and ready opinions … [and] Her mind moves liltingly and swiftly” (Schwaber 203). Moreover, Creasy’s claim that “error and education allow Joyce to explore the tensions between human agency and wider historical contingencies” (Creasy 60) draws attention to the complex dynamic between the errors of Ulysses' academic men and Molly Bloom’s unlearned frankness: where their scholasticism fails to provide them with a valid understanding of the world, her lack does not. Molly’s “acuity and mental richness” (Schwaber 203) based on a more intuitive understanding and located “at the margins of the education system” (Creasy 69) is no less unique or cerebral due to its formal ignorance, and may even be strengthened by her disavowal of rigid educational backgrounds—ones that often cause Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus to feel ostracised and isolated.

In order to further dissuade a reductive interpretation of Molly and female knowledge in Ulysses, O’Brien points to Joyce’s vast rewrites of the “Penelope” episode to insinuate that Joyce creates “An aesthetic of mobility” divorced from the gender-essentialist idea of an “écriture féminine” communicated through Molly (O’Brien 9). That is, contextualising her only with regards to the instances when Leopold or other male characters contemplate her relegates her to the margins of the novel based on the male gaze even though her vast linguistic presence should reify her as an individual in the text. Her personal intellect and experience also acts as the impetus for van Boheemen’s analysis of Molly, who describes their “endeavour [a]s no longer just a feminist one, [but a]s part of a poststructuralist enquiry into signification and subjectivity” (van Boheemen 69-70). Through Molly, van Boheemen believes that Joyce intended her to embody a verifiable truth through her linguistic play and affords her psychology a prioritised place in the cerebral hierarchy of Ulysses (70).

Ultimately, the analyses of Molly Bloom by Schwaber, Creasy, O’Brien, and van Boheemen suggest that her intellectual capacities and philosophical ruminations play an integral role in her characterisation in Ulysses and deserve to be addressed alongside her status as an uneducated wife and mother, not to mention as a sexualised woman often assessed through the male gaze. Furthermore, by reapplying the logic of their arguments to characters like Dilly Dedalus and Gerty MacDowell, these critics can contribute valuable insights into the role of female education and intellectualism alongside the emphasis on masculine logos in Joyce’s novel.

Case Studies

Two apt examples of the relationship between gender and learning in Ulysses surface when we consider Dilly Dedalus and Gerty MacDowell, since both are young girls with aspirations beyond their social stations:

For instance, Gerty laments that “had she only received the benefit of a good education [she] might easily have held her own beside any lady in the land” (U 13.99). Though Gerty “read[s] poetry … [and feels] that she too could write poetry” if she was able to improve her writing through institutionalised study (U 13.634-35), she makes mention of her reliance on “Clery’s summer sales” (U 13.159) to be fashionable and safeguards her nicest clothing (U 13.176-79). Since she is unable to follow the draw of masculinised scholasticism, she believes she has to attempt to manoeuvre the sphere of “love, a woman’s birthright” (U 13.200) through her “fashionable intelligence” (U 13.192) to locate social and economic security through marriage. Moreover, the sly and pointed manipulation of her body in the "Nausicaa" episode demonstrates how she uses her "feminine" knowledge to secure for herself the attention of Leopold Bloom, whom she refers to as “her dreamhusband” (U 13.431), as he masturbates to her on the beach. Through Gerty, we can see how women in Ulysses occupy a liminal position where their mental capacity is undergoes a contextualised translation process into feminised spheres: where male characters are free to wax philosophical about Shakespearean sonnets in the National Library due to their educational privilege (see "Scylla and Charybdis"), women like Gerty are forced to establish their prowess in more worldly—and therefore womanly—contexts.

Dilly Dedalus, as opposed to Gerty, is noted for her pitiable appearance by Bloom (U 8.40-43) due to the destitution of her and her sisters who are reliant on their stingy father to provide for them (U 10.258-298). Since her brother Stephen was able to receive a Jesuit education and study in Paris, Dilly feels shame and “laugh[s] nervously” just from asking Stephen's opinion on a second-hand copy of Chardenal’s French primer that she was able to buy with pawned money (U 10.863-68). Instead of feeling pride that she would hope to emulate his learnedness, he feels guilt and remorse due to her incessant and immobile poverty:

"She is drowning. Agenbite. Save her. Agenbite. All against us. She will drown me with her, eyes and hair. Lank coils of seaweed hair around me, my heart, my soul. Salt green death" (U 10.875-77).

Since “education beyond primary level for girls remained 'unusual'” (Creasy 69) in early twentieth century Ireland, Dilly does not share Stephen’s status as the privileged male child who can outrun his deteriorating family by providing for himself through his education. Instead, Stephen’s female siblings are forced to pick up the crumbling pieces of the domestic life assigned to them in lieu of their deceased mother, whereas Stephen, influenced by his greater degree of autonomy, is able to leave Dilly and his sisters to succumb to their social inopportunity. Furthermore, Dilly's drab appearance renders her situation even more demoralising since she is unable to transfer her intellectualism to feminised spheres the way Gerty does.

◇◇◇

On a Reddit thread posted by Jef_Costello of Eve Arnold's photo of Marilyn reading the 1934 American edition of Ulysses, user Siddboots comments: “She’s up to Molly’s soliloquy. Hot.” Bookwolf responds: “That was the first thing I noticed too. It’s downright pornographic” (Jef_Costello). Similarly, the comments on a Reddit thread posted by Generalguyz include:

Craigyboy2601: "Good God that's attractive."

Jovadzig: "Lucky she managed to hold the book the right way up. You can actually see the strain on her as she attempts to remember how to read."

MrToadEsquire: "Yeah Baby. Pretend to read Trial of Socrates next. Uhhhhhhhhh."

Widgetas: "(Am I the only one who never really found her attractive?)"

As these comments demonstrate, even when people do not completely dismiss Monroe's ability to read Ulysses, they still condemn her to their overtly objectifying lens. Though passages in Ulysses that integrate the interiority of women display them as just as complex as educated characters like Leopold Bloom or Stephen Dedalus, its insinuation that women and men are afforded different types of academic possibility—especially when attractiveness comes into play—still rings true when compared to these kinds of reactions shared nearly a century after its initial publication. Ultimately, the baseless scrutiny against Monroe, a woman renowned for her sensual appeal and affected ditziness, regarding her ability to comprehend the 1934 American edition of Joyce's novel featured in Arnold's photo draws attention to the intellectual constraints placed on women and acts as an intriguing stepping-off point from which to interrogate the perpetuation of cultural and intellectual misogyny both in and outside of Ulysses.

Works Cited

Articles

“John Walker’s A Critical Pronouncing Dictionary.” British Library, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/john-walkers-a-critical-pronouncing-dictionary. Accessed 27 November 2022.

“Marilyn Monroe Reads Joyce’s Ulysses at the Playground (1955).” Open Culture, 8 November 2012, https://www.openculture.com/2012/11/marilyn_monroe_reads_joyces_ulysses_at_the_playground.html. Accessed 24 November 2022.

Bénéjam, Valerie. “Molly Inside and Outside ‘Penelope.’’” European Joyce Studies, vol. 17, 2006, pp. 63–74. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871272. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Conway, Richard. “On Bloomsday, Marilyn Monroe Reading Joyce’s Ulysses.” Time, 16 June 2014, www.time.com/3809940/marilyn-monroe-james-joyce-photo/. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Creasy, Matthew. “Error and Education in ‘Ulysses.’” European Joyce Studies, vol. 20, 2011, pp. 57-72. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871320. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Generalguyz. "Marilyn Monroe Reading James Joyce's Ulysses." Comments by Craigyboy2601, Jovadzig, MrToadEsquire, and Widgetas. Reddit, 2010, https://www.reddit.com/r/pics/comments/h9xo1/marilyn_monroe_reading_james_joyces_ulysses/. Accessed 29 November 2022.

Jef_Costello. “Marilyn Monroe Reading Ulysses.” Comments by Bookwolf and Siddboots. Reddit, 2010, https://www.reddit.com/r/books/comments/hj4bo/marylin_monroe_reading_ulysses/. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Edited by Hans Walter Gabler et. al., Penguin Random House, 2022.

O’Brien, Alyssa J. “The Molly Blooms of ‘Penelope’: Reading Joyce Archivally.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 24, no. 1, 2000, pp. 7–24. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3831697. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Parkes, Adam. “‘Literature and Instruments for Abortion’: ‘Nausicaa’ and the ‘Little Review’ Trial.” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, 1997, pp. 283–301. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25473814. Accessed 30 Nov. 2022.

Schwaber, Paul. “The Vitality of Molly Bloom.” The Cast of Characters: A Reading of Ulysses, Yale University Press, 1999, pp. 198–224. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1dszzxc.10. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Van Boheemen, Christine. “‘The Language of Flow’: Joyce’s Dispossession of the Feminine in ‘Ulysses.’” European Joyce Studies, vol. 1, 1989, pp. 62–77. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44871175. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Images

Arnold, Eve. Marilyn Monroe Reading Ulysses by James Joyce, Long Island, New York, USA, 1955. Artsy, www.artsy.net/artwork/eve-arnold-marilyn-monroe-reading-ulysses-by-james-joyce-long-island-new-york-usa. Accessed 27 November 2022.

British Library. “Ulysses by James Joyce, 1934, American Edition.” British Library, www.bl.uk/collection-items/ulysses-by-james-joyce-1934-american-edition. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Erwitt, Elliot. "New York, USA, 1954, American Actress Marilyn Monroe." Holden Lutz Gallery, https://www.holdenluntz.com/artists/elliott-erwitt/marilyn-monroe-new-york-reading-book/. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Unknown. "The 430 Books in Marilyn Monroe's Library: How Many Have You Read?" OpenCulture, 2014, https://www.openculture.com/2014/10/the-430-books-in-marilyn-monroes-library.html. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Unknown. "James Joyce's Women." Cineplex, http://moncineplex.ca/Movie/james-joyces-women/Photos. Accessed 27 November 2022.

Unknown. "The Secret Diary of Marilyn Monroe." BBC, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160601-the-secret-diary-of-marilyn-monroe.