Affective Ambiguity of Ulysses versus Ulysse in the Introduction of "Sirens"

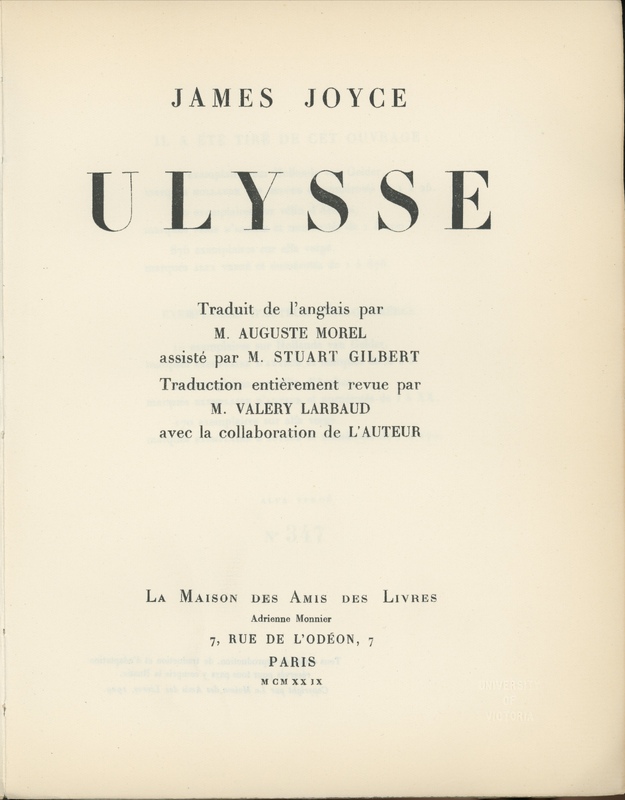

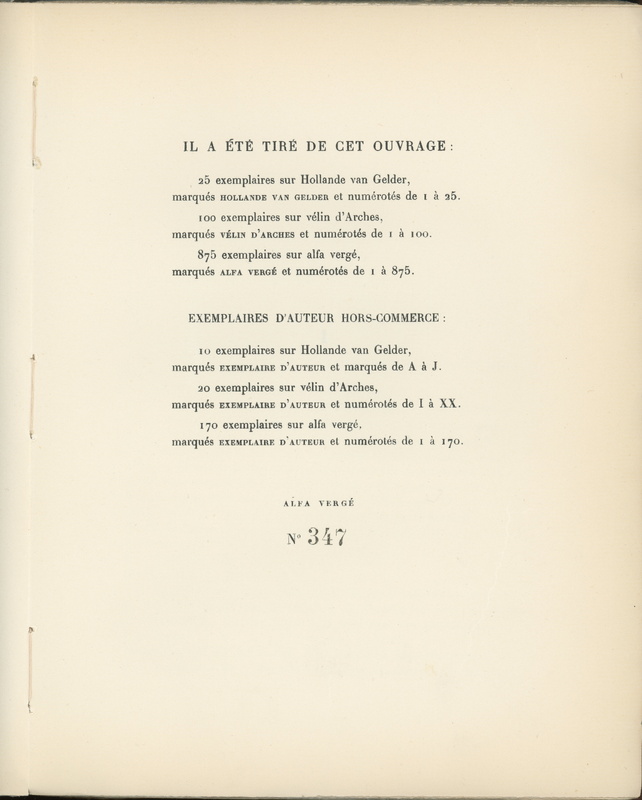

The first French translation of Ulysses, Ulysse, hit the shelves in 1929, translated by Auguste Morel. There are 875 copies of the “alfa vergé” edition, and the 347th copy resides in the Special Collections archive at UVic. In terms of physicality, Ulysse is minimally bound, larger, and heavier than other editions of Ulysses at Special Collections. Although uniquely constructed, I am specifically interested in how Joyce’s experimental English prose was translated to French, and how this translation would be received orally.

Ulysses is filled with colorful, ambitious language and sentence structures. Though difficult, the novel can be read aloud to unlock a new paradigm of meaning. In fact, the entire "Sirens" episode is almost certainly meant to be uttered instead of thought. In the Gilbert schema, the Art of the episode is “Music” and the Organ of the episode is “Ear”. This begs the question: what editorial choices were made when translating such an English - that is, linguistically English - novel to French? The French language does not even have a “th” sound! The "Sirens" episode is unique because of its musicality, but it was most likely written with an English phonetic in mind. For instance, the second sentence of the episode (“Imperthnthn thnthnthn.”) is essentially impossible to recreate in French precisely because of the lack of a “th” sound. Yet, if the importance of this episode is on the sound of the words then, ideally, someone who knows neither English nor French should feel the same thing while listening to a recording of each version. Thus, does Morel's translation invoke the original affective vocality of "Sirens"?

So, this page will contain two vocal recordings of the opening sequence of "Sirens": one in English and one in French. These recordings will aid in answering the following: “How does the sound and feel of the French translation differ from an English edition?” As a hypothesis, I began this project with the assumption that the French translation will sound far from the English version simply because this episode seems to rely heavily on the nature of English phonetics. As such, the feeling and mood created will not be similar. By the end of this page, I hope to convince you that this hypothesis stands - but for a different reason.

As a disclaimer, I have spoken a colloquial Quebecois version of French for most of my life around my family and usually not in formal settings. Additionally, in recent years, I have spoken significantly less French than when I was growing up. As such, the French I speak sounds drastically different from French that would be heard in Paris in 1929. Many of the formal elegancies are lost. I naturally place less strictness on pronunciation and more importance on choice of word or speed. As such, my reading of Ulysse may be warped in comparison to how Morel intended the reader to pronounce certain words in 1929. Moreover, I will inevitably impose my own tone and cadence while reading. Nevertheless, I hope you enjoy the overconfident bastardization of this beautiful episode with the grimey sound of a Francophone who is slowly losing their fluency.

"Sirens" in Context

Before trying to draw any conclusions, it is important to situate ourselves with some arguments critics have raised surrounding “Sirens” and its opening sequence. These ideas will paint a better picture for us to understand how Joyce initially attempted to simultaneously synthesize and distill language and sound.

The intersection of orality and literacy are deeply explored within Ulysses. Specifically, in “Proteus,” Stephen ponders how best his poetry can be delivered and received:

Who watches me here? Who ever anywhere will read these written words? Signs on a white field. Somewhere to someone in your flutiest voice.

In Oral Tradition, Sabine Harbermalz describes this as Stephen’s struggle with “the medium through which he will address his audience: a written text as opposed to an oral performance” [1]. Habermalz then expounds on the diametric situations writers and speakers face when creating or performing their art. A speaker has a listener, while a writer is alone, pen to paper. The dulled sentiment of “signs on a white field” could be interpreted as Stephen’s fear that his writing will be meaningless to a reader. Contrarily, a speaker could make his writing meaningful or entertaining to an audience “in [their] flutiest voice.”

Following this train of thought, “Sirens'' is considered to be Joyce’s attempt to experiment with the vocality and musicality of language. The opening of the episode has been interpreted in many ways. Linguistically, in Joyce Studies Annual, Patrick Milian describes the opening as “Joyce shifting the reader’s attention from language’s meaning to its material and materiality” [2]. More narratively, Scott J. Ordway describes it as “a literal distillation of the episode to come” [3]. Musically, Zack Bowen points out in his book Bloom’s Old Sweet Song the opening sequence “clearly constitutes an overture” [4].

However, Joyce was writing in English. From 1922 to 1929, the French translation, Ulysse, began to take form with Auguste Morel leading the translation team. Although Joyce was writing Finnegan’s Wake, he consistently aided Morel. In fact, according to Liliane Rodriguez, correspondences between the team indicate that “to avoid dissatisfaction with the French translation, Joyce remained involved and committed during the seven years” [5]. Translating Ulysses into French - or any language - is a harrowing task. Other than Morel and Joyce’s translation in 1929, it has only been done once: in 2004 by Joycean scholar Jacques Aubert. In James Joyce Quarterly, Flavie Epié compares the differing creative choices both translations make in “Sirens.” Unsurprisingly, Epié notes that the translator of “Sirens” found it to be “by far the most challenging” [6]. We will be analyzing Morel’s translation, which was approved by Joyce [5][6], so we can assume the choice of diction in Ulysse has a degree of artistic integrity. Indeed, whether the translated opening sequence of “Sirens” feels the same as the English original is up to the audience - and the flutiness of the speaker’s voice.

The Sound And The Language

Above are the two audio recordings of me reading the opening sequence of “Sirens” in French and English. I urge you to listen to both uninterrupted and to remember your listening experience when reading the following.

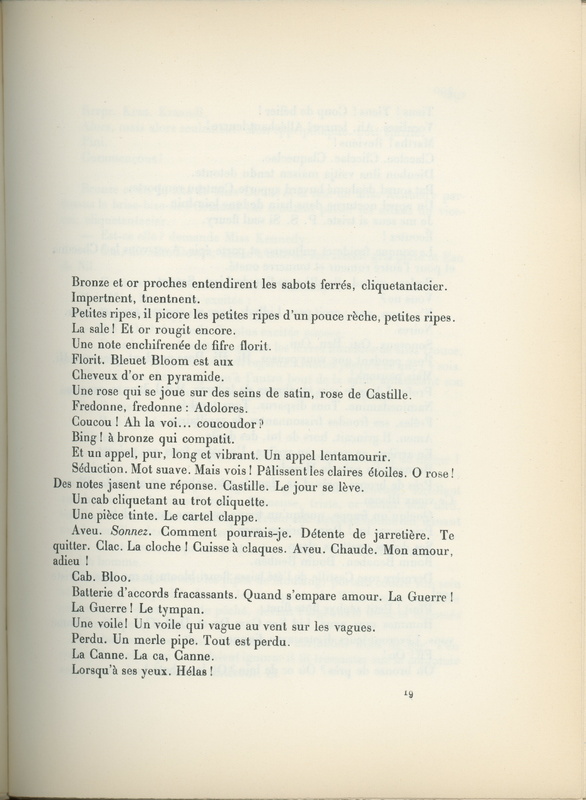

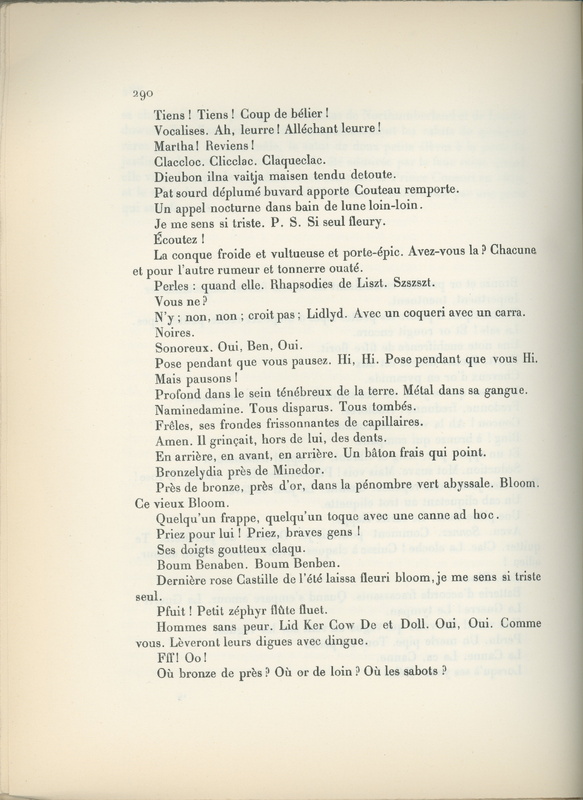

Before discovering Joyce approved and contributed to Morel’s French translation, I posited the following hypothesis: the French translation won’t feel like the English because "Sirens" was written with English phonetics in mind. After listening to both recordings, I believe my hypothesis stands. However, my reasoning is wrong. We are toying with subjectivity but I believe Morel and Joyce do a fantastic job at bringing similar cadence, emphasis, and tempo from the original English to the French translation. Admittedly, some small passages have completely different pronunciations. For instance, “Hissss.” becomes “Szszszt.” and “Horn. Hawthorn.” becomes “La Canne. La ca, Canne.” Funnily, the English sexual innuendo here becomes a French pun for ‘caca’ – meaning poop... Where there is Joyce, there are feces. Overall, despite these small differences, the differing feelings do not come from the phonetic makeup of the English original versus the French translation. There is more to it than just mapping differing sentiment to differing phonetics.

At this point, meaning and comprehension must be differentiated. Based on Ordway and Bowen’s comments, we know the sequence is introductory to the episode, musically and narratively [3][4]. The introductory aspects of the sequence thus lend it some purpose. However, isolating the opening sequence leaves us in a conundrum. With no narrative context, is the sequence meaningless? Julia Kristeva, a French literary theorist, developed a theory for language that relies on the distinction of “semiotics” and “symbols” in her book Revolution in Poetic Language. To Kristeva, symbols map to grammar and syntax, allowing people to use words and letters as referential tools. On the other hand, semiotics map to rhythm and vocal tone, allowing people to imbue affect and sentiment into their communication. The combination of these two elements are necessary for language. Without symbols, people would simply groan and moan back and forth to each other. Without semiotics, people would not know how to derive importance between words [7]. Using this theory, symbolically, the sequence certainly seems to border on meaninglessness given its unorthodox structure. Semiotically, not so. By reciting the sequence, we are capable of giving it a “body,” as Kristeva would say. Through deliberate speed, rhythm, and intonation, a recital of the sequence allows the sequence to flourish with substance. Further, knowing that Joyce contributed and approved Morel’s translation [5][6], we can infer that Joyce was pursuing these ideas at the linguistic level. That is, the opening sequence is not a meditation on English, but language as a whole.

As such, I credit the differing feelings that arise between the English and the French recordings to the incomprehensibility of the entire passage. Given its narratively unintelligible nature, how is it supposed to communicate anything but a feeling? The absence of a conventional narrative lends the speaker a license for creativity. From the sultry eroticism (or is it unloving hostility?) of “Avowal. Sonnez. I could. Rebound of garter. Not leave thee. Smack. La cloche! Thigh smack. Avowal. Warm. Sweetheart, goodbye!” to the mournful beauty (or is it childish whining?) of “I feel so sad. P. S. So lonely blooming.” ending with the suspensefully climactic (or is it playfully contradictory?) “Done. Begin!”, reciting the opening sequence creates a vignette of incongruous, emotionally provocative figments that wash over the listener and evoke any feeling.

With this in mind, the sequence wholly depends on its incomprehensibility. The language that it is composed of is irrelevant, and so is drawing symbolic meaning from it. To reiterate Milian’s statement about the opening sequence, the sequence’s essence lies in the “materiality” of the language [2]. If anything, the lack of narrative cohesion serves to make the sequence more mysteriously alluring. In an oral setting, this sequence metaphorically places the speaker at an altar performing Latin Traditional Mass while the listener is, as Bloom would say, stupefied. In this stupefied state, the listener is brought into their own trancelike world. They’re left to their own devices yet engaged by the speaker, guided by the pure sound of voice. Whether it be Latin, English, or French, if you can’t reason about what you’re listening to, all you’re left with is how you feel about what you’re listening to. These manufactured feelings and lack of sense consume the listener, making them submissive to Joyce's song like a sailor submitting to a Siren. These 65 lines are Joyce at his desk in the New Vatican, writing a new liturgy in English (or is it French?), and sitting back to watch us get brainwashed by the sound of his voice years after his death - all the while not uttering a damn word.

Bibliography (IEEE)

[1] S. Habermalz, “‘Signs on a white field’: A Look at Orality in Literacy and James Joyce’s Ulysses,” Oral Tradition, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 285–305, 1998.

[2] P. Milian, “Bronze by Goldenhair: Music as Language in ‘Chamber Music’ and ‘Sirens,’” Joyce Studies Annual, pp. 175–205, 2016.

[3] S. J. Ordway, “A Dominant Boylan: Music, Meaning, and Sonata Form in the ‘Sirens’ Episode of ‘Ulysses,’” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 85–96, 2007, doi: 10.1353/jjq.0.0030.

[4] Z. R. Bowen, Bloom's Old Sweet Song: Essays on Joyce and Music. University Press of Florida, 1995.

[5] L. Rodriguez, “Joyce’s Hand in the First French Translation of Ulysses,” in Renascent Joyce, University Press of Florida, 2013, p. 122–141. doi: 10.5744/florida/9780813042459.003.0010.

[6] F. Epie, “Creative Processes in the Two French Translations of ‘Sirens,’” James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 57, no. 1–2, pp. 141–146, 2020, doi: 10.1353/jjq.2019.0109.

[7] J. Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.