Fixing What Isn't Broken: Hans Walter Gabler and the Importance of Error in James Joyce's Ulysses

Abby Flight

Introduction

In 1984, Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Steppe, and Claus Melchior published a critical and synoptic edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, with the goal of establishing a definitive and “corrected” version of the text. The Gabler edition was published in New York by Garland Publishing in three volumes, and received generally positive reviews. By tracing how the text of the novel has changed through repeated publication, the Gabler edition attempts to “conserve intact” (Gabler et al. viii) the conclusive Ulysses, uncorrupted by the errors and intentional changes that arose in each new edition. The simple yet striking design of this edition emphasizes the idea that it is somehow authoritative, with the golden bow on the cover reminding the reader of the illustrious Greek epic from which the novel draws inspiration.

This edition is intriguing because it presents itself as a definitive and exhaustive version of a novel that has been embroiled in controversy and censorship since the moment of its initial publication. Given the thousands of changes to the original text over the last century, it is a difficult and extremely subjective process to determine what qualifies as the true Ulysses, or whether there really is a true Ulysses at all. The Gabler edition presents two different manuscripts, one of which illustrates each minute change between editions and another which purports to offer a “new original text” (Gabler et al. viii) which corrects these various “corruption[s]” (vii). While this edition is clearly the result of substantial scholarly effort, it is difficult to accept the claim that this edition is somehow definitive. Considering the many intentional errors within the text, as well as the novel’s commentary on the multiplicity of truth, I am more inclined to view each edition of Ulysses as representing one unique aspect of its long and complicated history, rather than having scholarly value only when dissected and altered to fit an ideal version of the text. Additionally, Ulysses had existed for sixty-two years prior to the publication of the Gabler edition; given that the novel was well-established in the scholarly and public consciousness during this time, I find it difficult to accept a version that lacked “a public existence” (Gabler et al. viii) prior to 1984 as the definitive version.

Using the Gabler edition, I will explore the role of error in the publication history of Ulysses, and consider the impact of error in preventing the establishment of a definitive version of the novel. By focusing on intentional and accidental errors within the novel, I will reveal how error is a defining factor of Ulysses, and therefore cannot be “corrected” or erased without compromising the essence of the text itself. I argue that Gabler’s edition is not definitive, and there cannot be a definitive version of Ulysses because of the vital role that error plays in defining and redefining the novel.

Literature Review

Since the initial publication of Ulysses in 1922, the novel has been notorious for its abundance of textual errors. Hundreds of printing errors plagued the first edition (Rossman 98), and attempts to remedy the situation in subsequent editions have had little success, creating new errors for each one they corrected. In examining the relationship between Ulysses and its errors, some scholars have reached the conclusion that attempting to rid the novel of misprints robs it of one of its key ideas. Patrick McCarthy argues that “the inevitability of error” (195) is a central theme of Ulysses, represented throughout the novel by purposeful misspellings, interpersonal miscommunications, and blatantly incorrect statements from characters and narrators alike. To “correct” Ulysses, careless mistakes would have to be separated from “carefully placed misprints” (McCarthy 200), an impossible task which would inevitably result in yet another imperfect text. Additionally, by utilizing error as one of the text’s primary themes, Joyce “appropriate[d] error as his own device” (McCarthy 208) while he wrote the novel, creating a situation in which every unintentional error reinforces the purpose of the intentional errors. Tim Conley advances a similar argument, asserting that Joyce predicted the typographical errors that would pervade Ulysses through “literary self-awareness” (15) and perfected an “aesthetic of error” (149) that would seamlessly incorporate them into the fabric of the novel. Conley also interprets the inevitability of error in Ulysses as Joyce’s modernist critique of an imperfect world failing to live up to its ideals of progressive utopianism (23), an idea that both intentional and accidental errors equally support. Since Ulysses represents even the most mundane aspects of our world in extensive detail, it is fitting that the imperfections of day-to-day life should be included as well.

Gabler’s 1984 edition of Ulysses exemplifies the ongoing debate over both the novel’s errors and the quest for a definitive edition. While creating this edition, Gabler utilized an editorial technique known as genetic criticism, which Graham Falconer describes as an attempt to trace “the mechanics of creativity” (8) by comparing “variant states” (3) of a work in order to find or produce an authoritative version. As Falconer points out, such an approach necessitates a view of the text “as a single object” (13) uninfluenced by outside forces, an idea which the ongoing processes of error within Ulysses directly contradict. While Gabler’s edition is meticulous and traces the development of the novel over time, it is no more immune to error than its predecessors. In his examination of the controversy surrounding this edition, Mark Wollaeger points out that creating a new version of a text is a “profoundly personal” (95) process and requires subjective decision-making. Because of this, the editor’s views significantly alter the final product, and Gabler’s strong opinions (Wollaeger 92) likely created a dramatically different “definitive version” than would have resulted under a different editor. Charles Rossman also sees the process of editing as a “social and historical” (100) influence on the construction of a novel over time. He argues that the controversy regarding Gabler’s 5,000 changes (Rossman 99) to the original novel had an overall positive effect, but not because they constituted a definitive Ulysses. Instead, Rossman suggests that this edition increased reader awareness that all versions of Ulysses are edited versions, and a pure, unfiltered Ulysses is “simply not accessible” (Rossman 100).

While Gabler’s edition of Ulysses is a thorough investigation of the novel’s publication history, an examination of academic literature concerning the novel and its history of error indicate that it is not a definitive edition of the text. Because of the historical processes of error that have influenced the text since its inception, as well as the overall significance of error to the novel’s themes, there can be no authoritative Ulysses, as the thousands of intentional and accidental errors within the text are vital to the novel’s message and ensure that aspects of the text will be altered with each new edition.

The Significance of Error in Ulysses

Throughout Ulysses, James Joyce uses error as a stylistic tool to portray the everyday mistakes that shape our perception. Typos and inaccuracies that appear throughout the novel teach us that our vision of objective truth is influenced by factors beyond our control. Similarly, the novel itself has been subjected to external forces of change which Joyce was unable to prevent. Ulysses has been transformed by error throughout its publication history, resulting in an understanding of the text as mutable and susceptible to error, which further supports Joyce’s argument. Because of this, I argue that trying to establish a definitive, “error-free” version of Ulysses, as Gabler did in 1984, both undermines Joyce’s comment on the inevitability of error and erases the continual processes of error that provide new support for this argument.

Joyce recognizes error as inevitable in the publication process. In episode sixteen, “Eumaeus,” the botched article recounting Dignam’s funeral provides an intentional, in-text example of how even small errors can alter our perception of reality. Among other mistakes, the article misidentifies Bloom as “L. Boom,” and includes both Stephen Daedalus and the fictitious “M’Intosh” as attendees (Joyce 529). Given the many people involved in writing, editing, and printing a newspaper, human error is unavoidable within the final product, and Joyce acknowledges this here with these small errors within the article. Editors and typesetters were likely responsible for textual errors such as the misspelling of Bloom’s name, and these same forces have continually altered Ulysses through repeated publication. While this has resulted in a text “replete with errors” (Gabler et al. viii), such errors reinforce the themes of the novel and therefore must not be erased. The novel’s intentional errors are not random or inconsequential; taken together, they provide a framework for understanding everyday life as defined by disorder, confusion, and inaccuracy rather than an organized structure. Endeavoring to “correct” the errors made during editing and publication is a futile attempt to make sense of the chaos that Joyce portrays as a crucial aspect of our world. To establish a “perfect” version of Ulysses is to ignore the flaws that underline its message: as humans we are imperfect, and that imperfection extends to everything that we create.

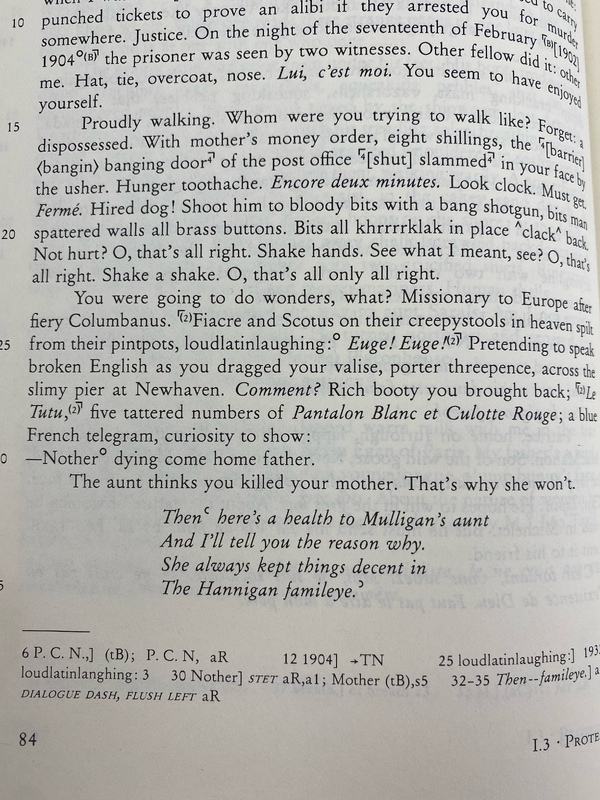

In addition to supporting the theme of imperfection, errors add new layers of meaning that enhance Joyce’s argument. In episode three, “Proteus,” Stephen Daedalus reflects on the telegram that called him home from Paris: “Nother dying come home father” (Joyce 35). This is an intentional error by Joyce, the implication being that the message was meant to read “Mother” and was altered at some point during transmission. However, some editions change “Nother” to “Mother” (Gabler et al. 84), under the assumption that they are correcting an error rather than creating one. Both the fictional and real-life errors are the same: one letter is changed, resulting in a different message. Because both mistakes demonstrate the same process of error, the unintentional error directly illustrates how easily the intentional error could have occurred in the first place. In this way, the processes of error that have characterized Ulysses’ continued publication are a self-renewing source of support for the “aesthetic of error” (McCarthy 149) that defines the text. Moreover, as both typos are examples of the mode of error that Joyce intended to convey in this instance, it is ultimately a matter of opinion as to which error best represents the authorial intent and supports the argument made by the erroneous telegram. Therefore, asserting that either is somehow definitive or “correct” erases an instance in which truth is subjective, opting instead to attempt to enforce an objective truth that the processes of error both within and outside of the text clearly reject. By arguing that the text “requires pervasive correction” (Gabler et al. vii), Gabler ignores these processes and robs Joyce’s argument of evidence that has built up over decades of publication.

When a novel is defined by intentional inaccuracies, every error is significant. Erasing the mistakes in various editions of Ulysses contradicts Joyce’s depiction of error as an inevitable part of both everyday life and human creations, and discounts the unavoidable processes of error that continually support this depiction. While Gabler’s 1984 edition of Ulysses successfully “records the work’s evolution” (Gabler et al. viii), it is not definitive. Throughout Ulysses, Joyce shows us that our error-filled world rejects a single objective truth, and this must be reflected when presenting a novel that incorporates error and resists perfection at every turn.

Conclusion

Understanding Ulysses as dynamic and ever-changing rather than as a static object is crucial to viewing the novel from Joyce’s modernist perspective and appreciating the processes of error that influence our understanding of the novel to this day. Every imperfection, whether intentional or accidental, offers fresh insight into how error shapes our sense of reality and truth, enabling us to dive deeper into what those concepts really mean in literature and in everyday life. Reading Ulysses requires us to suspend our understanding of what constitutes reality, and there is no better way to do this than by appreciating the variety of errors that continually alter the makeup of the novel itself. By appreciating the role of error in Ulysses, we gain a better understanding of Joyce’s authorial intent as well as the function of error in shaping literary works over time.

Works Cited

Conley, Tim. Joyce's Mistakes: Problems of Intention, Irony, and Interpretation. University of Toronto Press, 2003.

Falconer, Graham. "Genetic Criticism." Comparative Literature, vol. 45, no. 1, 1993, pp. 1-21.

Gabler, Hans Walter et al. Introduction. Ulysses, by James Joyce, 1922, Critical and Synoptic Ed., Garland Publishing, 1984, pp. vii-viii.

Joyce, James. Ulysses, Critical and Synoptic Ed., edited by Hans Walter Gabler, Claus Melchior, and Wolfhard Steppe, Garland Publishing, 1984.

Joyce, James. Ulysses. Vintage Classics, 2022.

McCarthy, Patrick A. ""Ulysses": Book of Many Errors." European Joyce Studies, vol. 22, no. 22, 2013, pp. 195-208.

Rossman, Charles. "Introduction: A Special Issue on Editing Ulysses." Studies in the Novel, vol. 51, no. 1, 2019, pp. 98-103.

Wollaeger, Mark. "Ulysses, Gabler, and Kidd: The Personal Note." Studies in the Novel, vol. 51, no. 1, 2019, pp. 86-97.