Marquis of Hastings: Protestant Books, Freemason Teaching

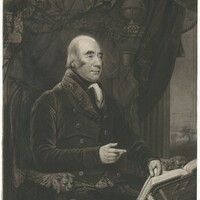

Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquis of Hastings

Tall upstanding, strong and athletic, with very thick, black whiskers, Hastings was called the ugliest man in England. But this was balanced by his genial and affable manner. He was popular with the Army, kind and attentive to women, well read, dignified, scholarly and polite. He was devoted to his work, energetic and industrious. An ambitious and distinguished soldier with a flair for administration, he was never remarkable for political consistency at home, but in India he left his mark as an honest and effective ruler. ~ Charles Clive Bigham, Viscount Mersey; The Viceroys and Governor-General of India

To be sure, the University of Victoria’s 1610 edition of Acts and Monuments was most definitely owned by Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquis of Hastings, Earl of Moira. We cannot say where he acquired either volume, but we can see that he aquired them as a set since both volumes have the same endpaper with the same partially removed bookplate. We also, safely, assume that he claimed—not necessarily acquired—both volumes between the years 1816-1826 because he does not have the title of “Marquis” until 1816.

Hastings is most notable for his work as a Governor-General of India from 1814-1823, but his military efforts began during the American Revolution as an Adjutant-General to the British Expeditionary Force. His time in America and India helped distinguish him as a prominent war General. As Hastings moved from continent to continent, from country to country, and county to county, it is possible, but unlikely, that he acquired Acts and Monuments while in America or India.* It is much more likely that he acquired the books around 1806 when George Galway Mills was sent to King's Bench for his debts.

It is also possible that Acts and Monuments was bought by Hastings in an act of exuberance. Although he was distinguished in war, it is often remarked that he struggled with keeping up with his personal finances. In the inventoried list of the “Hastings’ Family Papers” there are records of multiple estate sales and transactions indicating debts owed. Therefore, it is not outside the realm of possibility that Hastings acquired the two volumes as he would acquire anything else—as mere objects that illustrate wealth.

It is safe to assume that Francis Rawdon-Hastings was deeply invested in English Freemasonry. Named after his maternal uncle, Hastings not only carried his uncle’s name, but also carried on the tradition of leading part of the Masonic order. To our knowledge, Hastings was Grand Master of the Free-Masons Society around 1804, Trustee of the Free-Masons Charity, and President of the Masonic Benefit Society until his death in 1826. It is also safe to assume that the Hastings (maternal family) were instrumental in establishing freemasonry as it is thought of today.

There is very little left linking Hastings’ maternal uncle to Freemasonry, but what is left is telling. Found in an inventoried list of the “Hastings Family Papers” is a document entitled “Conveyance of sentiments to Francis 10th EarI of Huntingdon from the Masonic Order” dated 1724. Because the English Masonic Order was still in its early stages as of 1720, any documents dated around that time would indicate deep investment. As for the lack of documentary material, that is not surprising. In Masonic teachings, it was, and still is, absolutely taboo to discuss freemasonry outside of the society.

“…despite its emphasis on tradition, transmission and authority, Freemasonry has always been a non-dogmatic organization in the sense that its rituals, symbols and practices have not had official and final interpretations. On the contrary, Freemasonry is characterized by a striking diversity of interpretation—it is thus possible to find purely moral interpretations of its central symbols, but also scientific, psychological, and esoteric, political, philosophical, religious etc. interpretations of the same symbols…” (Bogdan 1).

To better understand the relationship between Freemasonry and Protestantism, it is important to understand that “there is a generally recognized close relationship between the Protestant movement…and Freemasonry; They are sometimes even considered as parent and child, as expressed in the Hamburger Fremdenblatt, June 13, 1917 for the two hundredth anniversary of Freemasonry (1717) and the four hundredth anniversary of the Reformation (1517)” (Liagre 162). In this way, it is possible that Hastings owned Acts and Monuments because it perfectly represented both his Masonic and religious sensibilities. Assumedly, Hastings identified as some sort of Protestant because of his early involvement with the Whig Party in England. It could be, that Hastings wanted to own a copy of Acts and Monuments because it stands as a testament of religious nonconformity. At their most fundamental, Protestantism and Freemasonry share a distaste for Catholicism and the mediation that is inherent in Catholic religious teachings.