William Crispin: Religion on the Margins

Who was Hand C?

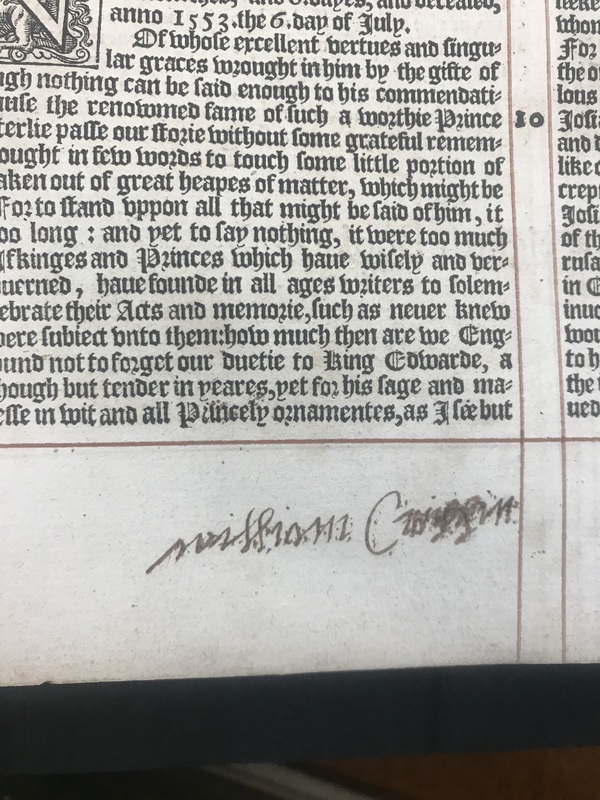

The annotations on page 1178 by Hand C are unique in the McPherson Library copy of the 1610 Acts and Monuments in that they contain both a given name and a surname: William Crispin. All other hand-written marginalia within the volumes is either unsigned or includes a given name only (ex: Hand A's Matthew and Hand R's Richard).

The same hand added additional notes on page 1189 and, helpfully for our purposes, once more signed William.

Reading for Clues

The annotations are written in secretary hand — a style common to the 16th and 17th centuries. By dint of the book's publication date, we can further narrow the likely timeframe of the annotation from 1610-1700.

We are doubly fortunate in that the annotations on page 1189 contain the phrase loving and kind friend, which is a direct quotation from James Janeway's book Heaven upon Earth; or the Best Friend in the Worst of Times, published in 1670. 1670 is therefore the terminus post quem or the earliest possible date for the action to have occured.

Though it is quite possible that Hand C signed someone else's name in the margins of Acts and Monuments, we believe it is reasonable to assume that Hand C was himself named William Crispin. The two most likely William Crispins to be writing notes between 1670-1700 are Captain William Crispin and his son, William Crispin IV.

William Crispin IV was baptised in 1653 but after that point there are no known records of his life. As his younger brother, Silas Crispin, was considered the eldest male heir of the Captain in 1681, we must assume William Crispin IV predeceased his father and likely died in childhood (Crispin, 1929b).

Captain William Crispin (1627-1681) lived a fascinating life, during which he engaged in state-sanctioned piracy while in the Royal Navy, participated in a failed coup to overthrow the Commonwealth and restore Charles II to the throne in 1656-57, and, in 1681, died en route to North America where he intended to help establish the colony of Pennsylvania with his friend and relative-by-marriage, William Penn (Hough, 1898; Crispin, Crispin, Goldolphin, Clerk and Cock, 1929).

If Hand C were indeed Captain William Crispin, then his naval background might explain why he chose to write his name on page 1178, which contains a large woodcut featuring a ship.

More suggestive, though, are the connections we might read into the text of the annotations themselves. Hand C has on page 1189 written a series of notes: the quote from James Janeway loving and kind friend, the words thou + thee, and the name William. Both thou + thee and William have been intentionally smudged in an attempt to efface their content. These notes are significant in light of Captain William Crispin's relationship to Quakerism.

Religion on the Margins

In the 17th century, the Quakers, or Society of Friends, were considered "dissenters" — meaning that they were Protestants who disagreed with the Church of England on certain important religious issues. Dissenters, and Quakers in particular, were subject to suppression and were persecuted under laws such as the Quaker Act of 1662. In North America, from 1659-1661, The Massachusetts Bay Colony executed three Quakers for refusing to abandon their religious beliefs (Endy, 1973; Vann, 1969).

At the time Hand C was writing notes in Acts and Monuments, espousing Quaker beliefs openly was both illegal and highly dangerous.

During the 1670s, Captain William Crispin was living in Kinsale, Ireland, and was connected to a nearby underground network of Quakers through his friendship with William Penn, who had himself been disinherited and imprisoned for his Quaker beliefs (Endy, 1969). Crispin had hoped to help Penn establish a colony in North America founded on the principle of religious toleration where Quakers could practice their religion in peace. It was rumored that Captain Cripsin converted to Quakerism during his time in Ireland, but evidence for this conversion has eluded scholars — yet that is not especially surprising giving the necessary secrecy practiced by suppressed Quaker communities (Hough, 1898).

The annotations by Hand C have special resonance when considered within a context of Quaker belief and experience.

Loving and kind friend...

The Quakers referred to themselves most often as the Friends, so the quote from James Janeway declaring Jesus to be a loving and kind friend would have been very appealing to them. Janeway, though not a Quaker himself, was also a dissenter and had been subject to assassination attempts by members of the Church of England (Wilson, 1808). Like the Quakers, he was a member of a marginalized relgious group in a time when that meant risking imprisonment, torture, and even death.

thou + thee

The English pronouns thou and thee had long been considered old-fashioned by the 1670s. One of the only contexts in which thee and thou were still frequently used was in the speech and writing of Quakers (Vann, 1969).

In light of the common association of thee and thou with illegal Quakerism, it may not be surprising that after making his notes, Hand C smudged the wet ink away, leaving only a trace of his words. Likewise, he also tried to remove his name from the page.

Captain William Crispin as Hand C

Captain William Crispin's life fits the dates for Hand Cand positions the writing of the marginalia between 1670-1681. His Quaker and naval connections provide explanations for both the placement and content of Hand C's annotations.

If Hand C is Captain Crispin, then it is tempting to argue that his annotations capture an early stage of his (previously) undocumented conversion to Quakerism. He would have been familiarizing himself with the new and special meanings of words like: friend, thee, and thou.

When we consider the controversial and revolutionary origins of Foxe's Acts and Monuments, it seems fitting that a later generation of religious freethinkers were writing their own secret history in its margins.

Works Cited

- Crispin, Jackson M., William Crispin, Joseph Godolphin, William Clerk and C.G. Cock. "Captain William Crispin." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 53:2 (1929), pp. 97-131.

- Crispin, Jackson M., William Crispin, Joseph Godolphin, William Clerk and C.G. Cock. "Captain William Crispin: Errata." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 53:3 (1929), p. 202.

- Crispin, Jackson M.. "Captain William Crispin Continued." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 53:3 (1929), pp. 193-202.

- Crispin, Jackson M.. "Captain William Crispin Concluded." The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 53:4 (1929), pp. 289-321.

- Hough, Oliver. “Captain William Crispin, Proprietary's Commissioner for Settling the Colony in Pennsylvania.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 22:1 (1898) 34-56.

- Janeway, James. Heaven upon Earth; or, the Best Friend in the Worst Times. Early American Imprints, 2004.

- Wilson, Walter. The History and Antiquities of Dissenting Churches and Meeting Houses, in London, Westminster, and Southwark: Including the Lives of Their Ministers, from the Rise of Nonconformity to the Present Time: With an Appendix on the Origin, Progress, and Present State of Christianity in Britain. W. Button & Son, 1808.

- Endy, Melvin B. William Penn and Early Quakerism. Princeton University Press, 1973.

- Vann, Richard T. The Social Development of English Quakerism. Harvard University Press, 1969.