Margaret Jourdeman: The Witch of Eye

Writing a "Witching" Retraction

Margaret Jourdeman is a staple in subsequent editions (incl. UVic’s 1610 edition) of Acts & Monuments, not because of the legend around her life, but because of the hotly contested arguments involving alleged accusations that Foxe included her as a martyr in his earliest edition. The controversy triggered a momentum of early scholarship, wherefore notable Protestant and Catholic writers took it upon themselves to debate the legitimacy of the accusations against Foxe and, notably, Margaret’s reputation as a potential treasonous witch. As a result, Margaret becomes a prominent figure in post-Reformation scholarship, as England debated the legitimacy of both the accusations against Foxe and the sovereignty of opposing religious authorities.

History of the Legend

Margaret’s presence in Foxe’s Acts & Monuments is eerily similar to the way Pope Joan’s image is used in post-Reformation literature. Yet, unlike the fictional Pope Joan, Margaret can be traced back to a real individual—though her reputation, which lasted long after her death, is borderline fictitious.

The legend of the “Witch of Eye” can be traced back, in part, to the Mirror for Magistrates—a political poem dated around 1559 (Freeman 344).

“There was a Beldame called the wytch of Ey,

Old mother Madge her neyghbours did hir name

Which wrought wonders in countries by heresaye

Both feendes and fayries her charmyng would obay

And dead corpsis from grave she could uprere

Suche an inchauntresses, as that tyme had no peere”

(Freeman 344).

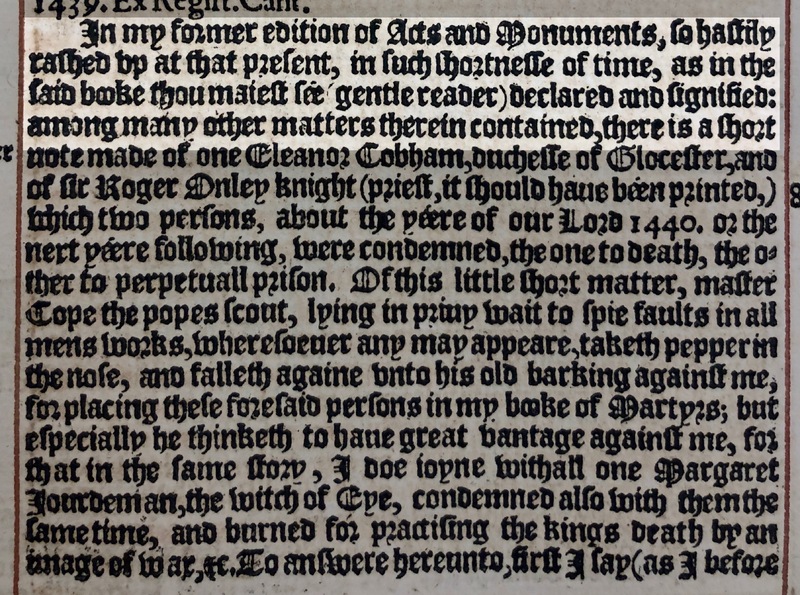

However, Foxe does not portray the story of Margaret Jourdeman in the traditional sense, but rather in a retraction written in his defence of accusations levied against him by his Catholic critics: “In my former edition of Acts and Monuments, so hastily rashed up at that present, in such shortnesse of time, as in the said booke thou maiest see (gentle reader) declare and signified…” (Pictured below: Foxe 645)

It should be noted that the earliest edition Foxe chose to include the Margaret Jourdeman retraction can be traced back to 1570 and, notably, is still present by the 1610 edition—demonstrating ongoing relevance in the scholarly and religious discussions that were taking place during the height of Acts & Monument’s popularity.

Text Debated

The man that sparked the controversy resulting in Foxe’s long-lasting retraction, was Catholic apologist Nicholas Harpsfield (i.e. Alanus Copus). Harpsfield published Dialogi in 1566, whereby he openly criticized Foxe’s Acts and Monuments. The Latin passage brings Foxe to account regarding the perceived error of including Margaret Jourdeman in his earliest edition—a woman convicted and executed for committing treason and witchcraft in the mid-fifteenth century (Freeman 1).

However, despite Harpsfield’s account, Foxe vehemently denies that he ever wrote about Margaret Jourdeman in his book: “Margaret Jourdeman I never spake of, never thought of, never dreamed of, nor did ever heare of, before you named her in your booke your selfe. So far is it off, that I either with my will, or against my will, made any martyr of her” (Pictured below: Foxe 645). Foxe takes great offense to Harpsfield’s accusations and, in retaliation, goes as far as to imply that Harpsfield made it up “[him]self” (Foxe 645).

Foxe continues on to try and separate himself from any association with Margaret Jourdeman and the “witch” image that plagued her own legacy. Yet, in an effort to hedges his bets in discrediting Harpsfield, Foxe extends a peculiar sentiment regarding Margaret’s reputation as a witch: “what occasion have you thereby to slander me and my booke with Margaret Jourdeman: which Margaret, whether she was a witch or not, I leave her to the Lord” (Pictured below: Fox 646).

Despite including a retraction/defence against Nicholas Harspfield, the topic continued to be a popular point-of-reference for notable Catholic critics of Foxe’s book of martyrs. Robert Parsons in particular continues Harpsfield’s original criticism in a section of his 1603 Treatise of Three Conversions of England—a critical Catholic companion detailing perceived errors in Foxe’s Acts & Monuments:

“Behould how little John Fox dareth to stand to his owne proofes…For yf his proofes and reasons against their condemnation be not sure and found; then remayne they traytors, witches, and sorceryeres, as they were aduidged, and no Martrys nor Confessors. Which point in effect Fox heere yeldeth unto. And therby yow may iudge, as well of these, as of the rest of his Calendar Saints” (Parsons 272).

“For though he was warned and reprimended for the fame by Alanus Copus (or Doctor Harpesfield) in his Dialogues, and his madness therin shewed most evidently: yet is he not ashamed to come with yt againe in this his fifth edition, changing only the name of Knight into Priest in Roger Onley” (Parsons 269).

Parsons does not hold back in his take on the long-standing debate; he not only dismisses Foxe’s detraction, but implies that he continues to make the same errors. However, Parsons does take a similar route as Foxe, subtly implying that it is not up to him to judge whether or not Margaret was a witch or a traitor, but since Foxe did not provide sufficient evidence to the contrary, neither himself nor Foxe can assume that Margaret is not more than she was “aduidged” (Parsons 272). As a result, Parsons uses the example of a controversial female figure (just as Harpsfield did) to try to discredit Foxe and his controversial book of martyrs.

The Female "Villain"

Similar to Pope Joan tainted image, the mythology surrounding “witchcraft” associated with Margery Jourdeman’s reputation played a role in the ongoing match between Catholic and Protestant dissent. The female body (in particular women labelled as witches) is used as part of ongoing literary dissent—both within Acts & Monuments and critical literature—debating religious authority in post-Reformation England.

Works Cited

Foxe, John, 1516-1587. Actes and Monuments of Matters most Speciall and Memorable Happening in the Church: With an Universall Historie of the Same. Printed for the Company of Stationers, London, 1610.

Freeman, Jessica. "Sorcery at Court and Manor: Margery Jourdemayne, the Witch of Eye Next Westminster." Journal of Medieval History, vol. 30, no. 4, 2004, pp. 343-357.

Parsons, Robert, 1546-1610. “A Treatise of Three Conversions in England, 1603-1604.” English Recusant Literature, 1558-1640. Vol. II, Scolar Press, Ilkley England, 1976.

Harpsfield, Nicholas, 1519-1575. Dialogi Sex Contra Summi Pontificatus, Monasticae Vitae Sanctorum Sacrarum Imaginum Oppugnatores. Belgium, 1566. Image: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ucm.5316858519 (picture Digitized by Google. Original from Universidad Complutense De Madrid)