Women on the Edge

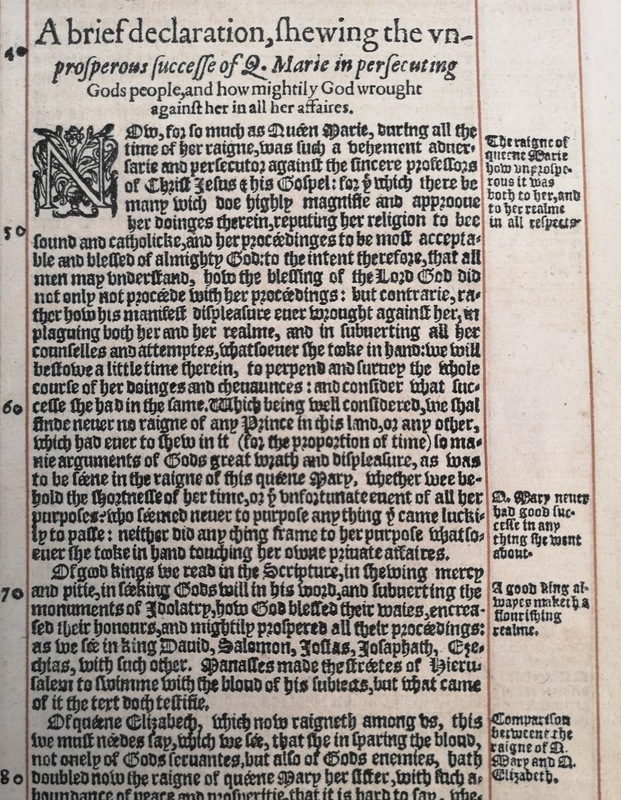

The use of printed marginalia stems from a long tradition of rubrication in medieval manuscripts. Having marginalia in early modern printed books accentuated its affiliation with the older traditions of textual production as most manuscripts dating from the twelfth century onward contained a form of marginalia (Slights 3). By examining the margin, one can view a claim of ownership over the text and an assertion of authority over both the contents of the book and the reader. In John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, his marginalia establishes his authority over both the text and the reader, marking a claim over the printed words and those who read the text.

There are, however, other purposes of marginalia beyond allowing the author to claim ownership of their own text. Sometimes, the purpose of marginalia can be to acquire authorities who contribute supplementary information about the subject of the main text; other times, annotators can undercut the assertions or instructions of the primary author, wanting instead to place their own interpretation on the subject. Every time, however, marginalia is strategically placed, frequently reprinted, and regularly cited throughout the early history of printing in England (3).

Some scholars such as Evelyn B. Tribble, Elizabeth Eisenstein, and Roger Chartier argue that printing should be understood as a cultural agent rather than a passive medium. A popular theory is that the margins and the main text were in fluctuating relationships of authority; the margin might “affirm, summarize, underwrite the main text block and thus tend of stabilize meaning, but it might equally assume a contestatory or parodic relation to the text by which it stood” (Tribble 6). However, precisely because the margins are in a shifting relationship to the text, they allow the reader to view the competing claims of internal authority and plural, external authorities in the margins of the text.

Printed Marginalia in John Foxe's Acts and Monuments

This is the perspective that John Foxe’s Act’s and Monuments is best viewed through. His utilization of marginalia was often meant to support the main text, but, at times, was simultaneously used to challenge it if he did not agree with what was being said.

The best examples of his marginalia is best seen through his interactions with Lady Jane Grey, Queen Mary I, and Queen Elizabeth I. John Foxe used his marginalia to influence his readers into developing the same opinion and interpretation of these women. With Lady Jane, he crafted the persona of a devout and courageous young woman – the ideal Protestant Martyr.

For Queen Mary I, Foxe utilized his marginalia to subtly undermine her words and actions. He implemented key words that would unconsciously bias his readers against Mary. Beginning with her introduction in the volume, it continued throughout the text up until Queen Elizabeth’s coronation.

The marginalia of Queen Elizabeth are similar to Lady Jane’s, shaping the readers into open admiration and love of the Protestant Queen who ousted the Catholic Mary.

The printed marginalia in Acts and Monuments reflect the thoughts and feelings of John Foxe, placed strategically throughout his book to both inform and manipulate readers. Their influence is subconscious, always remaining at the edge of the page but never quite merging with the main text.

Their presence allows Foxe to shape the personas and the characterizations of the people within his book to his own liking, seeking to constitute a community of readers sharing a set of doctrinal beliefs (Tribble 7). While printed marginalia constitutes only a fraction of the main text, the cultural, contextual, and authorial information it conveys is immense and significant. It was a way for Foxe to retain his authority over his readers even centuries after his death.

Their presence allows Foxe to shape the personas and the characterizations of the people within his book to his own liking, seeking to constitute a community of readers sharing a set of doctrinal beliefs (Tribble 7). While printed marginalia constitutes only a fraction of the main text, the cultural, contextual, and authorial information it conveys is immense and significant. It was a way for Foxe to retain his authority over his readers even centuries after his death.

Rather than being a battle of marginalia notes and biblical citations, the voice of Foxe becomes harmonious with his content, working together to guide each reader through the text and cause them to emerge sharing the same ideas that Foxe held when he constructed his Acts and Monuments.

Section author: Emma Usselman