John Foxe: Why Include an Anglo-Saxon Sermon in Actes and Monuments?

John Foxe was ordained by deacon Nicholas Ridley on 24 June 1550 and became a member of England’s Protestant elite (Freeman para. 9). One aspect of Foxe’s attempts to promote the Protestant cause in England was to publish works that argued for the absurdity of the Catholic church’s doctrine of transubstantiation: his major work condemning the transubstantiation doctrine was Syllagisticon (para. 43). In the Catholic tradition during Foxe’s time, the eucharist was viewed as a literal event: the bread and wine served at communion literally transformed into the body and blood of Christ (Sands 447). This doctrine of transubstantiation viewed the eucharist as word becoming flesh (448). Protestant reformers (including Foxe), however, viewed the doctrine of transubstantiation as heretical as they believed the eucharist was a commemoration of Christ’s sacrifice rather than a literal repetition of it (453).

With this context in mind, it becomes more clear as to why Foxe included this particular Anglo-Saxon sermon about transubstantiation in Actes and Monuments. Foxe sought to not only champion Protestant theories of the eucharist through a sermon that posits this event as a metaphorical commemoration but also to establish the Protestant cause through an indigenous form of English religion stemming from the Anglo-Saxon period (Echard 27, Murphy 517-518).

It is likely that Foxe did not have a working knowledge of Old English, but, rather, accessed Anglo-Saxon texts through Latin translations (Murphy 517). Therefore, it is siginifcant that Foxe chose to reproduce Ælfric’s sermon in Old English rather than Latin. This strategy sought to show that Protestantism was not heretical, but rather a return to the true teachings of the English (Anglo-Saxon) church (517). Moreover, in early modern England, Catholics were suspicious of vernacular editions of biblical texts as they feared that vernacular translation would produce errors and heresies (François 27). Between 1407 and 1409 Archibishop Thomas Arundel issued the Oxford Constitutions which prohibited the translation of the Bible into English without the approval of a local bishop or a provincial council (32). Even owning an English translation of the Bible could result in a charge of heresy (32). Protestant reformers, however, sought to produce vernacular biblical texts to promote individual readings of the Bible, rather than having the Bible translated through a church official (27). Therefore, Foxe’s choice to reproduce a biblical sermon in English was a statement that championed Protestant beliefs that the Bible should be produced in the vernacular.

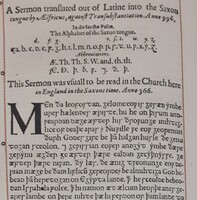

By aligning Protestant doctrine with the ancient and authoritative Anglo-Saxon church, Foxe intended to build a relationship between Protestantism, a fairly new religious sect in early modern England, and Anglo-Saxon doctrine in an attempt to give Protestantism a long-standing historical authority (Echard 27). To accentuate this tie, Foxe, rather than including a modern translation of Ælfric’s sermon on transubstantiation, reproduced the sermon in its original Old English using a typeface that sought to accurately represent Old English letterforms (29-30). By representing the text as authentically as was possible in an early modern printed book, Foxe established an authenticity and prestige to Protestant claims about the eucharist through an indigenous English language (29-30). Moreover, Foxe translated this authenticity to his own work Actes and Monuments and gave his claims authority.