Lady Jane Grey

Oil Portrait of Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey (c. 1537 – 12 February 1554)

The Lady Jane Grey ruled England for only nine days before her reign ended at the hands of Queen Mary. Her fleeting time as a monarch was marked by her unsuccessful attempt to maintain Protestant rule in England, an act that caused her to be viewed as a Protestant martyr for centuries afterwards, granting her the title: “The Traitor-Heroine” of the Reformation (Biography).

Jane became queen after the death of her cousin, Edward VI, in 1553. The accession was created under the machinations of the Protestant Duke of Northumberland, who was the acting regent to Edward VI and Jane’s father-in-law through her marriage to Lord Guildford Dudley. His act of having the king declare both Mary and Elizabeth illegitimate caused the line of succession to pass to Jane, despite her tenuous claim to the throne.

On 10 July 1553 Jane was proclaimed queen and support for Mary grew rapidly, causing many of Janes supporters to abandon her until, finally, on 19 July 1553, the Privy Council of England proclaimed Mary as queen, deposing Jane. With public support on her side and a strong political backing, Mary condemned Jane and her supporters to death (Morrill).

Lady Jane Grey’s sovereignty and execution at the Tower of London at just sixteen years of age has inspired a legend to grow around her, especially from Protestant supporters such as John Foxe. Although her time as queen was an attempt by Northumberland to control the throne through his son and daughter-in-law, it was also a bid to shore up Protestantism and keep Catholic influence at bay. Jane's reign may have been brief, but the impact she made on the Protestant community was lasting, causing her image and persona to be lauded and venerated for centuries afterwards.

Grey in Foxe: Her Protestant Canonization

Fecknam: "Madam, I lament your heavie case, [and] yet I doubt not, but that you beare out this sorrow of yours with a constant and patient minde."

Jane: "You are welcom unto me sir, if your coming be to give Christian exhortation. And as for my heavy case (I thank God) I do so little lament it, that rather I account ye same for a more manifest declaration of Gods favour toward me, then ever be shewed me at anie time before: And therefore there is no cause why eyther you, or other, which beare me good will, shoul lament or be grieved with this my case, being a thing to profitable for my soules health."

The shown passage is the first introduction that Foxes' readers get to Lady Jane Grey. It records a purported conversation between Lady Jane and Master Feckenham (rendered Fecknam) who was Queen Mary’s own Master Chaplain. Fecknam was sent in an attempt to reconcile Jane to the Catholic faith during her imprisonment in the Tower of London. Although the actual meeting was never recorded, it is shown here by Foxe that the results of this conversation are a triumph for the Protestant faith. Readers can see from the marginalia exactly who the persona is that Foxe is beginning to construct for Jane, praising her for “comfortably tak[ing] her trouble” in this time of distress. Foxe is creating for his readers a calm young woman who remains steadfast in the face of adversity; unflappable even when faced with difficult questions and yet gently persuasive even when she is not trying to be.

Foxe continues to develop this persona throughout his Acts and Monuments, giving his readers an image of a woman worthy of the title of Protestant martyr.

It must be noted that this was published after the Protestant Queen Elizabeth had triumphed over the Catholic Mary, thus rendering the accuracy suspicious with no one to claim otherwise. However, even though the conversation was not a trial transcript and was written by a highly partisan account, it does reveal some of the central issues that divided Catholics and Protestants at the time (Oxford First Source).

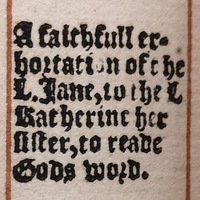

Jane Grey’s words and actions have appeared in multiple texts and volumes over the centuries. She was an educated young lady, taught Greek and Latin at an early age and proficient in French, Hebrew, and Italian. Her schooling and comportment played a large factor in her martyred status, garnering both sympathy and outrage over the fate that befell the protestant queen.

Foxe showcases Jane’s acts of piety and suffering to demonstrate her religious devotion. In Foxe’s eyes, Jane can do no wrong. Every word that drops from her lips is sanctified. Most significantly, he uses her letters and speeches to support the Jane Grey of his marginalia, rather than using his marginalia to support the Jane Grey of reality.

This is an example of just one of the many modifiers Foxe uses to describe Jane. They are subtle messages sprinkled throughout his marginalia meant to influence readers. It is a type of forced interpretation common in Bibles and theological treaties. In this instance, Foxe is utilizing his marginalia to guide his readers into viewing Lady Jane Grey in an undeniably positive light, free from scrutiny.

As it can be seen with these printed marginalia, Foxe is guiding his readers to view Lady Jane in a very specific manner. He is strategically employing pious language, highlighting the devout actions and words of Jane seen in the main passage. Indeed, Foxe is cleverly highlighting the aspects of the passage he wants readers to pay attention to. He imparts her “Good Intent,” assuring those reading that Jane is trustworthy. Similarly, he emphasizes her “Faith” by recording each time she performs a prayer or acts in the name of the Lord.

Foxe is careful not to place too many marginal notes, instead artfully scattering them throughout the margin columns just often enough to satisfy a reader who would be more interested in skimming the contents of the book rather than sit down and read the text themselves. If a reader should undertake such a massive endeavour, there a chance that they would not form the same characterization of Lady Jane that Foxe creates within his margins, instead creating for themselves a more realistic, earthly woman rather than a Protestant woman who could do no wrong. Although her shaping within the margins is subtly done, the end result is undeniable. They make it appear as if Foxe is merely relating the actions of Jane herself rather than crafting the persona for her.

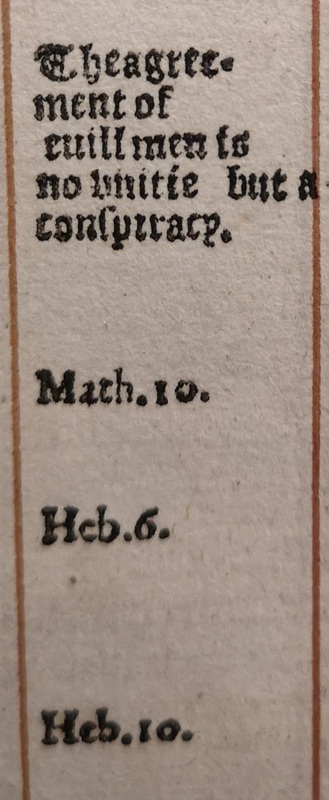

The citation of Bible passages is one of the most common occurring instances of printed marginalia in Foxe’s work. It was a way of identifying the biblical references placed in the writings of various people. For Lady Jane, it was Foxe’s way of demonstrating that she was a proper Protestant woman who had knowledge of God’s word. Lady Jane would often insert biblical references within her letters. Foxe used his margins as a means of highlighting them and to support his cultivated image of a devout Christian. Furthermore, the juxtaposition of naming “evil men” with Matthew 10 and Hebrew 6/10 is an excellent way of further positioning Jane away from the corruption of the court.

The Death of Lady Jane Grey

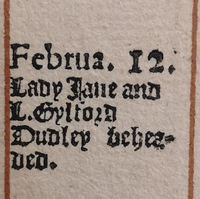

The death of Lady Jane Grey garnered more attention from John Foxe than the death of Queen Mary. There are no fewer than three marginalia notes dedicated to the event, a fitting indication for the amount of regular text dedicated to the beheading. The first piece of marginalia identifies “The words and behaviour of the Lady Jane upon the Scaffold,” drawing the attention of the reader to the stately behaviour of Jane even in the face of her impending death. The second piece of marginalia dates to February 12 when both Lady Jane and Lord Dudley were beheaded. While not graphic in its own right, when placed in context with other deaths found in the book the description of the death takes on a vivid imagery.

Foxe spent page after page creating a persona of Lady Jane for his readers to love and admire for her courage, faith, and unwillingness to compromise her beliefs. He calls specific attention to her final words – a right he did not even grant Queen Mary later on. By labeling both Jane's and Dudley’s death's a beheading, Foxe illustrates in great detail what befell this Protestant martyr and her husband. There is no subtly with this description, but rather a harsh reality in which Foxe forces his readers to confront their unfortunate ending and thus place Catholics in an even more negative light. There is no mercy in this marginalia, only a stern condemnation of the actions of Queen Mary and her Catholic counsel.

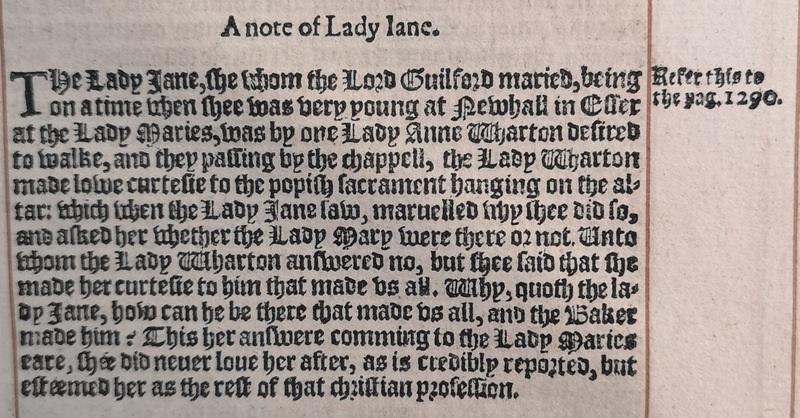

A Note of Lady Jane

While not an example of printed marginalia, it is significant to note the insertion of “A note of Lady Jane.” Nearly every other piece of writing about Lady Jane stemmed either from her own hand or from other’s letters to her. This note was likely penned by Foxe himself and shows a side of Jane often not typically acknowledged. By the end of the seventeenth century, the English people perceived Lady Jane Grey as the ideal young victim: beautiful, modest, deferential, quiet, and passive (Levin 92). However, Foxe himself commended Jane being sharp and vehement, declaring that it came from an earnest and zealous heart. Rather than being a passive victim, she was “self-examining, fanatical, bitterly courageous” (Chapman 56). This note highlights the backbone present in the Lady Jane.

Scholars have described Lady Jane Grey in a multitude of ways: the “stuff of which the Puritan martyr is made” (Chapman 56), having as “burning religious zeal which lit up the character of a rather simple girl” (Mathew 144), being “easily manipulated ... confused and bewildered” (Barrett 156) and “straight forward and unrelenting” (Snook 50). However, there remains the fact that Foxe heralded her virtue, focusing in particular on her refusal to violate her faith and on the details of her subsequent execution (Marsden 504). He crafted this persona within his margins and we would be remiss not to acknowledge his skill in manipulation of both readers and page boarders alike, creating the image of a young girl who would later go on to become of the most popular Protestant martyrs of the early modern era.