Pope Joan

Foxe's Female Pope

The graphic depiction of Pope Joan in Foxe's Acts & Monuments, sparked controversy within the Catholic community and contributed to the ongoing religious debates that took place in post-Reformation England. The use of the female body as the firing point for heated discussion, was a tool Foxe employed liberally throughout his well-known book of martyrs. As post-Reformation England sought to rebuild religious ordinance, through both establishing a Protestant history and disrupting the previous Catholic dominance, prominent discussions took place over women’s role within it—both female Protestants, Catholics, and mythic figures alike. Yet, just as female martyrs become part of the Protestant “ideal” of Christian women, so too are the non-martyr female figures contributing to Protestant idealism—albeit as cautionary examples. Pope Joan becomes one of several non-Protestant mythic female figures in Acts & Monuments whose depiction contrasts with the idealized image of the martyrs. The sexually charged image of Pope Joan as, alternatively, the Whore of Babylon, contributes to the contrasting female image and is meant to startle the post-Reformation reader, while unraveling and re-writing any remaining faith in the Catholic Church’s religious dominance in England. Therefore, Pope Joan is part of Early Modern post-Reformation propaganda that used longstanding distrust of female sexuality as a tool for instigating religious dissonance and denominational dominance.

The Legend of Joan

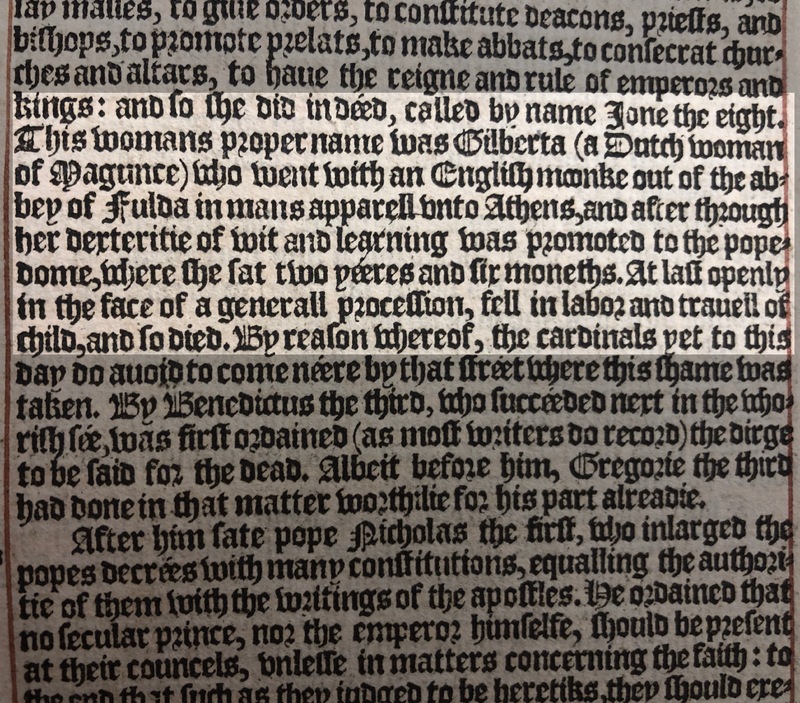

Although Foxe includes the basic details of the Pope Joan legend in his book, his version greatly differs in regard to the language and purpose behind the myth. Prior to the Reformation, Pope Joan was a known figure within Catholic mythology—though the likelihood of her existence (and the unlikely event that she was ever was Pope) had only been passingly debated. C. A. Patrides argues that the story of Pope Joan likely arose during the ninth-century, but the exact reason way is difficult to pin-down (Patrides 1). However, what is relevant is the perpetuation of the legend by notable Catholic writers, such as “Martinus Polonus [and] St. Antonius” (Patrides 1) who dedicated considerable literary discourse on the myth. Therefore, the legends surrounding the figure of Joan is already established, which is why Foxe’s attempts to unravel and discredit the myth merit attention:

“Jone the eight. This womans proper name was Gilberta (a Dutch woman of Pagunce) who went with an English monke out of the abbey of Fulda in mans apparel unto Athens, and after through her dexteritie of wit and learning was promoted to the popedom, where she sat two yeeres and six moneths. At last openly in the face of a generall procession, fell in labor, and travel of child, and so died” (Fox 124).

Yet, with the advent of post-Reformation identity building, the legend of Pope Joan resurfaces under a different lens to become a symbol for anti-Catholic sentiments.

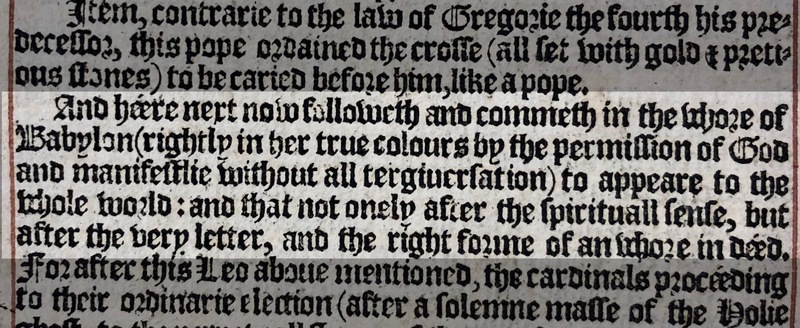

The Whore of Babylon

The startling and connotative image of the “Whore of Babylon” presides over the figure of Pope Joan in Acts & Monuments (pictured below). The second image below, taken from a Martin Luther bible and dated mid-sixteenth century, depicts a Protestant interpretation of the biblical figure. However, Foxe is quick to conflate the two mythic figures by re-identifying Pope Joan as the Whore of Babylon.

The name references the iconic image of evil from the Book of Revelations: “I saw the woman, drunk with the blood of the saints and with the blood of the martyrs of Jesus” (Revelations 17:6). The “Whore of Babylon” is associated with the kingdom of Babylon—a reference that Foxe ties closely to the Catholic Church. Therefore, through the alternative name, Foxe paints Pope Joan as the apocalyptic symbol of the Catholic Church.

The depicted conflation of the Whore of Babylon and the Catholic Church is a continuation of the post-Reformation identity building, meant to disrupt the legitimacy of the previous Catholic Church and establish the Church of England as the religious authority. However, Foxe’s controversial decision to portray Pope Joan as both a real historical figure and as a metaphor for the Catholic Church would not go unanswered…

A "Whore" Debated

Robert Parsons sets out to refute Foxe’s portrayal of Pope Joan by questioning her very existence as both a figure in history and as a symbolic image of the Catholic Church. Parsons works on laying a foundation for historical doubt regarding Joan’s existence; a move meant to discredit Foxe and help distance the Catholic Church from the legend. Parsons counters Foxe’s harsh language with similar inflammatory word choices, setting the fiery tone for the heated debates that would take place between the two.

“whom he calleth Pope Ioane. And albeit John Fox his words be as foolish and blasphemous, as they are wont in such cases: yet will I recyte them heere, to the end yow may see what truth or probability, this so much blazed & canvased hereticall fiction hath in yt” (Parsons 387).

Parsons uses a similar inflammatory platform as Foxe, directly attacking his (or anyone for that matter) credibility if they believe in the existence of Pope Joan: “this whole story of Pope Ioane is a mere fable, and so knowen to the learneder sort of Protestants themselves: but that they will not leave of to delude the world with it” (Pictured right: Parsons 391).

Parsons continues to use similar body-focused language, as he uses standard logic to present an argument against Foxe’s history of Pope Joan and attempt to refute the possibility that a woman would ever be elected to the Papacy:

“Yf she were young, that was against the custome to choose young Popes, as may appeare by the great number of Popes, that lived in that dignity above the number of Emperors, that succeeded often in their youthe. Besides it is a most unlikely thinge, that the whole Roman Clergy would choose a Pope without a beard, especially a straunger. But if she were old, when she was chosen, then how did she beare a child publikely in procession, as our heretiks affirme? how did they not discern her to be a woman or an Eunuch, seeinge she had no beard in her old age” (Parsons 403).

The focus on her female form, then, becomes the point by which Parsons hedges the unlikely event that a woman would ever have been able to deceive her way into the Papacy (as her body would have given away her gender). Therefore, even if Parsons refutes her existence, her female body still becomes the focus of the debate and the “evidence” used to discredit Foxe.

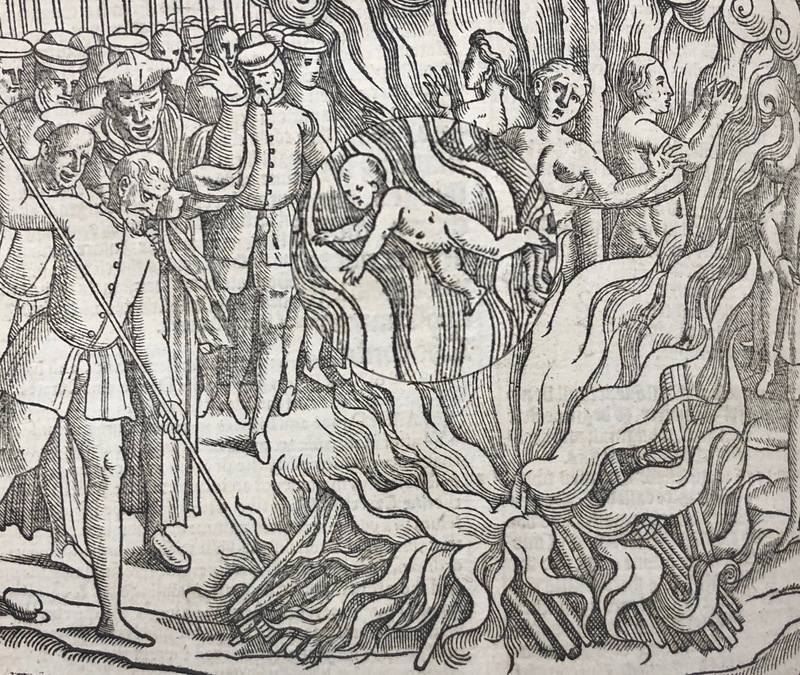

A Martyred Mother

As the debate raged on over the “whorish” image of Joan and her implied connection to the Catholic Church, Foxe chooses a peculiar section to include another reference to the famed female pope. Pope Joan returns in Foxe’s description of the martyred Garnsey Women: “The Defence of the 3 Garnsey Women” (Pictured left: Foxe 1767). At the centre of the woodcut detailing the execution of the Garnsey women, is the impromptu birth of a child. The startling image appears to whispers the horrific word infanticide, as the child himself is condemned to die because of his mother. However, Foxe makes a point to separate the implication of wrongdoing on behalf of the mother in the Garnsey execution and uses the example of Pope Joan as a figure that he implies actually committed such an atrocious the deed: “to the destruction of her child, when the needed not, as pope Joan, when thee might have kept her bed, would needs adventure forth procession, where both she herselfe, and her infant perished in the open street” (Foxe 1767).

Foxe’s maneuver creates an environment where the implication and the responsibility for the death of both Joan’s child and the Garnsey woman’s comes back to the story of Pope Joan—Joan as both the literal figure and the metaphorical one. Foxe does this because, according to Craig M. Rustici, the Garnsey child is “both born and died a martyr” (Rustici 74) and Pope Joan as the symbolic Whore of Babylon—a metaphor for the Catholic Church—becomes the focal point for the “atrocities perpetuated” against Protestants, which includes the death of the little “martyr” (Rustici 74). Therefore, even in subtle passing, the image of the female pope is used in the ongoing debate between the Catholic and Protestants vying for religious credibility.

The Debate Continued

The debate on Pope Joan was not just contained to Parsons and Foxe, but extended beyond to other notable scholars at the time. Alexander Cooke contributed his own take on the debate in his published 1610 defence of Foxe’s decision to portray Pope Joan as a historical figure: “Pope Ioane: A dialogue betweene a protestant and a papist. Manifestly proving, that a woman called Ioane was Pope of Rome: against the surmises and obiections made to the contrarie, by Robert Bellarmine and Cs̆ar Baronius Cardinals: Florimondus Rm̆ondus, N.D. and other popish writers, impudently denying the same” (Cooke).

This debate was so popular that, even as late as 1785, we see published editions continuing the defence of Foxe’s portrayal of Pope Joan and demonstrating the long-lasting influence of such a small reference in Acts & Monuments: “A present for a Papist: or, the history of the life of Pope Joan, from her birth to her death; Plainly Proving, Out of printed Copies and authentic Manuscripts of Popish Writers, and Others, That A Woman called Joan was really Pope of Rome, And was there delivered of a Bastard Son, in the open Street, as she was going in solemn Procession” (Humphrey).

Yet, while the tale of Pope Joan is most likely just a myth, what persisted quite vehemently was the existence of the religious debates that used her sexuality, body, and ascribed motherhood as a firing point between two rival religious authorities vying for dominance in a post-Reformation English world.

Works Cited

Foxe, John, 1516-1587. Actes and Monuments of Matters most Speciall and Memorable Happening in the Church: With an Universall Historie of the Same. Printed for the Company of Stationers, London, 1610.

Parsons, Robert, 1546-1610. “A Treatise of Three Conversions in England, 1603-1604.” English Recusant Literature, 1558-1640. Vol. I, Scolar Press, Ilkley England, 1976.

Rustici, Craig M. The Afterlife of Pope Joan: Deploying the Popess Legend in Early Modern England. University of Michigan Press, 2006.

“Revelations 17:6.” BibleGateway, https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Revelations+17%3A6&version=KJV. Accessed December 5th, 2018.

Patrides, C. A. “A Palpable Hieroglyphick: The Fable of Pope Joan.” Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800, vol. 123. Gale, Detroit Michigan, 2006

Cooke, Alexander. Pope Ioane: A Dialogue Betvveene a Protestant and a Papist. Manifestly Prouing, that a Woman Called Ioane was Pope of Rome: Against the Surmises and Obiections made to the Contrarie, by Robert Bellarmine and Cs̆ar Baronius Cardinals: Florimondus Rm̆ondus, N.D. and Other Popish Writers, Impudently Denying the Same. by Alexander Cooke. Printed [by R. Field] for Ed. Blunt and W. Barret, London, 1610.

Shuttleworth, Humprey, editor. A Present for a Papist: Or, the History of the Life of Pope Joan, from Her Birth to Her Death; Plainly Proving, Out of Printed Copies and Authentic Manuscripts of Popish Writers, and Others, that A Woman Called Joan was really Pope of Rome, and was there Delivered of a Bastard Son, in the Open Street, as She was Going in Solemn Procession. Printed for J. F. and C. Rivington, No 62, St. Paul's Church-Yard, London, 1785.

Burgkmair, Hans the Elder. The Whore of Babylon, 1523. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/da/Burgkmair_whore_babylon_color.jpg. Accessed December 5th, 2018.

Schedel, Hartmann. Joannes Septimus, 1493. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/30/Joannes_septimus.jpg. Accessed December 5th, 2018.