Anglo Saxon Influences in Foxe's Actes and Monuments

The Anglo-Saxon period in England spanned approximately from 400-1100 A.D., concluding politically with the Norman Conquest of 1066 (Webster 7). After the fall of the Roman Empire in Europe, there were extensive political and cultural transformations: successor states adopted Roman-style politics and new powers entered Europe from the north and east, including groups from Germany, Scandinavia, and the Frisian coast (7). Moreover, Christianity began to spread through Europe to pagan groups (7). Anglo-Saxon England, around the middle of the eleventh-century, became a unified kingdom characterized by a developed urban network, complex economy and legal system, specific coinage, centres of religion, and influential literature and art (7). Anglo-Saxon England was ethnically diverse: the Anglo-Saxons, themselves posited as an amalgamation of the “Angles,” “Saxons,” and “Jutes,” mixed with other groups including the Britons, Danes, and others that came to England during this period (Blair 4-5). Old English is the language specific to the Anglo-Saxons and was used from approximately 450 A.D. (when Anglo-Saxons began migrating to England) until the Norman Conquest of 1066 (Brinton 32-33). With the implementation of Norman French in England, the use Old English began to wane and Middle English increased in popularity among the English (35).

John Foxe attributes the Old English sermon published in the 1610 edition of Actes and Monuments to “Ælfricus,” also known as Ælfric of Eynsham, or Ælfric the Homilist who lived from approximately 950-1010 (Godden para.1). Ælfric was a Benedictine abbot of Eynsham and scholar educated as a monk under Æthelwold in Winchester (para. 1). Ælfric produced the Sermones Catholici between 990 and 995 which was a compilation of homilies, gospels, the saints, and doctrinal themes written in Old English (para. 2). The purpose of this project was to combat the coming reign of the Antichrist (with the approaching millenium) by providing the community with religious texts in the vernacular (para. 2). Ælfric hoped that these vernacular texts would replace what he believed to be heretical religious doctrine circulating in England (para. 2). Ælfric is celebrated for perfecting a form Old English which is used as a model for scholars to study Anglo-Saxon manuscripts and their grammar (para. 5).

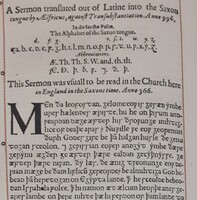

The opening to the sermon included in the 1610 edition of Foxe’s Actes and Monuments reads: “A Sermon tranഽlated out of Latine into the Saxon / tongue by Ælfricus, againഽt Tranഽubഽtantiation. Anno 996.” Ælfric’s translation was likely based on the Latin sermons in the Vulgate Bible which was translated by St. Jerome in 382 A.D. (officially completed c. 405 A.D.) and used by the early Roman Catholic Church (Encyclopaedia, Britannnica, Inc. 1137). This sermon concerns itself with transubstantiation as a symbolic, rather than literal, act which was at variance with the doctrine of the Catholic church during the time that Foxe produced Actes and Monuments (Murphy 518). As a Protestant, John Foxe wanted to legitimate the Protestant cause in early modern England and used this Anglo-Saxon sermon to bring authority to Protestant doctrine (518).

Section author: Hayley Copperthwaite