Patriarchal Assumptions and Women's Education

Virgin Martyrs

Very little is known about Young outside of Foxe’s short introduction, and the examinations themselves. Where her story came from is not explained, and “[t]here is also no manuscript evidence extant for Foxe’s detailed transcription of the examinations” (Hickerson 89). Further, although Foxe notes that she is “yet, as I heare say, alive,” it is unclear what has happened to her after she was released (Foxe 1874). The examinations end, and Young disappears. This silence is significant to an understanding of attitudes toward women during this time. Leading up to the early modern period, “the overwhelming majority of medieval Christian heroines were virgins, and when we examine the legends of those virgins we find that most of them were attractive young women who proved their love of God through their gruesome deaths" (Winstead 1). Literature surrounding virgin martyrs points to their "distinguished pedigree," and suggests virginity to be the "principle path to holiness” (Winstead 9; Yoshikawa 181). Young has children and is not a virgin. She is not young, being “fortie yeares and upwards” (1875). She was “of a middling- to lower-class status” (Gertz 111). Further, she does not die for her cause, but survives. In this, although it is significant that she is featured in the text at all, the sudden erasure of Young, who is arguably a hero of the Protestant faith speaks the narrow space that women were able to navigate within during this time. They were venerated for being virginal, tragic, and, importantly, silent. Young’s story pushes the boundaries of this fantasy, and confronts patriarchal assumptions surrounding women.

A Gentlewoman's Handbook

The English Gentlewoman, a conduct book written by Richard Braithwait and published in 1631, reveals some of the expectations surrounding female education in the early modern period. Braithwait explains, “[i]t suites not with her honour, for a young woman to be a prolocutor,” and that in front of men “it will become her to tip her tongue with silence” (89). Importantly, Braithwait states that well-bred women should not participate in “discourse of State-matters” and neither should they “dispute of high poynts of Divinity” (89-90)

Richard Cleaver and John Dod, in the 1598 text, A Godly Form of Householde Governement, explain the role of a wife as “a fellowe-helper,” and explain that the “gracious” and “virtuous” woman is “[t]o her neighbours ... humble, kinde and quiet” (Cleaver 52; 81-2). According to these men, a wife “may in modest sort shew her mind, and a wise husband will not disdaine to heare her advise, and follow it also, if it bee good,” but women’s primary duty during the early modern period was listening to men (82). This attitude is reflected in Young’s interrogations; In her fifth examination, the Bishop’s Chancellor, one of her main examiners, exclaims, “[w]hy, thou are a woman of a faire years: what shouldest thou meddle with the Scriptures? it is necessarie for thee to believe and that is enough. It is more fitte for thee to meddle with thy distaff then to meddle with the scriptures” (Foxe 1875). The distaff, which is a tool used in the spinning process, is “the emblem of female duty within the home” (Robinson 245). In her eighth examination, another important questioner, the Deane, asks, “Wouldest thou not bee at home with thy children and a good will? (Foxe 1877). Thus, as reflected in these conduct books, and in the attitudes of Young’s examiners, the patriarchal assumptions of this time silence women, and place them firmly in the home.

An Ill Favored Whore

In contrast to these attitudes, Young disrupts the system. Not only does she debate “with the savvy of a barrister,” she also “engages in a long theological argument with her interrogators,” which, as evidenced by Braithwait, Cleaver and Dod, was completely out of the realm of the permissible for women (Nieman 301; Hickerson 91). Because Young does not fit into the role of the virtuous woman, she is slandered. She gets called a “whore,” and “hereticke,” usually in combination with “traytorly,” sixteen times during her examination. It is “[p]recisely because of her considerable learning and her ability to articulate her beliefs [that] Young’s interrogators repeatedly accuse her of whoredom” (Hickerson 8). In fact, she is the “most subject to sexual innuendo and lascivious verbal attack” of all the Protestant women of the text (Hickerson 100). Such language during this time was a serious offense; as Ina Habermann explains, this sexual language could "resul[t] in loss of reputation," and so "sexual slander against a woman" was "actionable at the common law" (60). Thus, these insults are not mere moments of frustration, but rather instances of the examiner's intense rage at Young's inability to fit into the role they have assigned her. She is labeled promiscuous for not following the rules of virtuous womanhood during this period.

Twentie pound, it is a man in a womans clothes

During her fourth examination, Young is interrogated by six men. During one exchange, Young is pressured to perform a book oath, which, as Penelope Geng explains, was “used to police the speech of defendents” (676). Young is, “[u]nwilling to be so imprisoned by language” and “resists the oath by crafting a considerably more sophisticated counterargument based on her knowledge of the book of Matthew” (Geng 677). Young states,

To which one of her examiners, Sir Roger Cholmley, in sputtering disbelief at such biblical knowledge coming from a woman, exclaims:

This exchange speaks to Young’s surprising erudition and theological savvy. The verse she is quoting is Matthew 5:37, in which, during a sermon, Jesus warns against swearing, and advises saying only "yes," and "no," to avoid evil. Cholmley is shocked, "obviously refusing to believe that an opponent with so much emotional, intellectual, and physical mettle ... could hail from the ‘weaker sex’” (Nieman 302). Young’s apt use of the scripture quotation, along with Cholmley's blustering reaction to it, reveal how she disrupts the assumptions of these men to the point that they cannot even fathom that she is a woman. She is an enigma, and despite his accusation, only four sentences later, Cholmley ironically calls her “an ill favored whore,” (1874). Young is called “[a] man in a woman’s clothes and an ill-favored whore, virtually in the same breath" pointing to the fact that she is "a woman such as she is not supposed to be” (Mullaney 246). Young's intelligence of and scripture knowledge disrupt her examiners perception of virtuous womanhood and leaves them scrambling.

Literacy and Power

Young is evidently sharp; however, her level of education and literacy is unclear. Steven Mullaney asserts that while Young is “clearly of low birth,” she is “no less clearly literate, even though she seems to have had no formal education” (244-5). However, Penelope Geng and Genelle Gertz claim that she was illiterate (Geng 674; Gertz 120). This is because Young refers to hearing the bible read to her (Foxe 1875). As well, when questioned about the book she was distributing, she claims she “cannot tell” the name (1877). With these two examples, as will be explored more fully in the next section, Young could be feigning ignorance to trick her questioners. However, in her seventh examination, when asked to read and sign the transcript of the exchange between her and the Chancellor that had been recorded by a scribe, Young insists on hearing it read aloud (1877). This complicates the matter and makes Young’s literacy less clear.

To confuse the evidence even more, literacy during the early modern period is very difficult to track. As Retha Warnicke has discussed, although literacy rates have in the past been calculated based on how many people were able to sign their name, in recent years, it has been discovered that “far more people could read than could write or sign their names,” and so “historians have been unable to determine a method by which reading ability can be quantified” (153). Further, referring to England during the early modern period, she notes that “[t]here is abundant evidence that numerous people in this predominately oral society simply relied upon extensive memorization for their study of the Bible” (153). What little education and resources were available to women adds another layer of difficulty, as the "discrepancy between the sexes in terms of education was true at all levels of society” (Stone 158). Thus, given the difference in female education and the obscurity of literacy during the early modern period, it is difficult to determine to what extent Young was literate or educated.

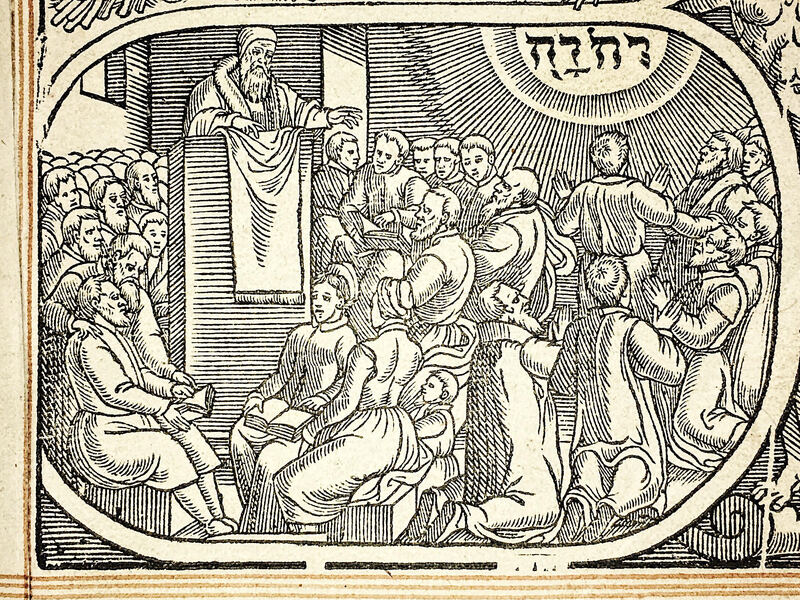

Despite this murkiness, it is particularly significant that Young is charged with distributing books. Whether she is literate or not, her examinations “giv[e] evidence that women were instrumental in circulating Protestant texts in Marian England” (Monta 7). This places Young in a position of power, as a giver of knowledge, a postition that was forbidden by her Catholic interrogators, who believed the Bible should be read only by the priesthood. For Protestants in particular, the female reader was a symbol of their "belief in the priesthood of all believers," and they "appeal[led] for the literacy of women as well as men so that all people may understand the scriptures for themselves" (King 43, 47). In the sixth examination, the Chancellor speaks to this tension, saying, “Thou has read a little in the Bible or Testament, and thou thinkest that thou art able to reason with a doctor that hath gone to schoole thirtie yeares” (Foxe 1876). He goes on, “thou beleevest nothing but what is in the scripture, and therefore thou art damned” (1876). Here, the Chancellor condemns Young for reading rather than obeying. Young counters, stating “I doe beleeve all things written in the scripture, and all things agreeable with the scripture, given by the holy Ghost unto the church of Christ, let forth and taught by the church of Christ” (1876). Here, she iterates an important order: reading comes first, then interpretation, then teaching. This order of faith, embodied by Young, upsets the patriarchal system of her interrogators.