The Catholic Queen

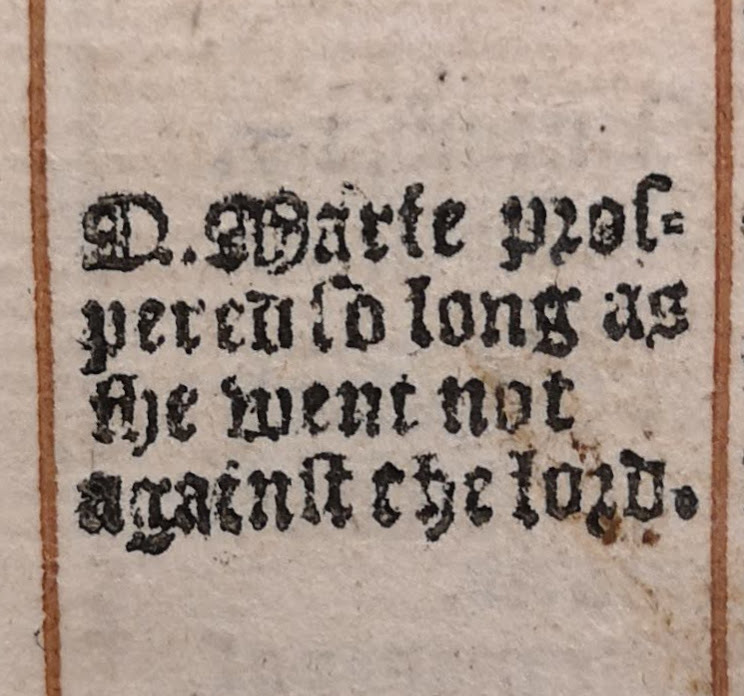

At first, Mary acknowledged the religious dualism of England, granting Foxe hope that the political and religious situation may not become too dire. Near the beginning of Foxe's coverage of her reign, he inserted various marginalia referring to this, such as “Q[ueen] Marie prospered so long as she went not against the Lord.” His opinion swiftly turned negative, however, when the desire to convert the country back to Catholicism became too great of a temptation to Mary, effectively alienating any Protestant supporters she originally had during her bid for the throne.

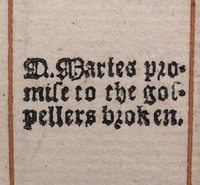

Marginalia such as “The raigne of queene Marie now unprosperous it was both to her, and to her realme in all respects” and “Q[ueen] Maries promise to the gospellers broken” began appearing throughout the pages corresponding with these changes. The margins mirrored the contemporary political climate of the time and the popular Protestant opinion of the queen.

The alienation became even more prominent after her marriage to King Philip II of Spain, a vain attempt to secure both the Catholic hold over England and prevent reversal of her reforms of her father’s religious edicts, including a strict heresy law. Within the marginalia, her marriage to Philip II is treated at first with distant description, merely identifying that the marriage occurred and when. Further into the text, however, when Foxe is given unspoken permission to speak poorly about the Spanish King due to his departure from England, he begins to venture into more verbose territory. He proclaims that “Queen Mary [is] left desolate of king Philip her husband” by his return to Spain. This evokes multiple emotions within the reader. First is pity for the queen who is so ravaged by emotion from his abandonment that she is literally “desolate.” This also has the double effect of making the queen appear weak and womanly by being susceptible to strong emotions, unfit to sit on the mannish throne of England. It then prompts the reader to gain a sense of outrage over the fact of Philips abandonment of his wife. It is unspoken that it was no doubt a result of his Catholic religion.

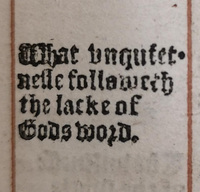

Foxe then writes about how “Lady Marie keepeth her self from the city of London,” thus keeping herself away from her duties as a queen. This prompts the reader to continue down the path Foxe had previously established of Mary being unfit to rule. Finally, Foxe accuses Mary of a “lacke of Gods word,” an accusation that had been hinted at but never blatantly stated before in the margins. Growing bold by the weakening of Mary’s grip on both her personal household and the kingdom, it was likely that Foxe now felt daring enough to express his true thoughts of the Catholic Queen. Although these are only three small examples of the marginalia written about Mary’s marriage, they are indicative of the tone Foxe set for his readers, encouraging them to view Mary in an empathetic though, ultimately, negative light.

This played a large role in the shaping of Foxe’s interpretation of Mary. At one point in the text he completely does away with verbal “padding” and gives a vicious account of how “more English bloud [was] spilled in Q[ueen] Maries time, then ever was in any kings raigne before her.” This is a double condemnation, acting as another subtle attack on her authority as a ruler and by casting doubt upon her ability to govern a country as well as her male predecessors. Foxe takes the time to point out that it is English blood being spilled – an unforgivable crime committed against the country itself. He also specifies the word “spilled,” highlighting both the grotesque nature of the deaths while simultaneously reminding his readers that this was a crime committed by the “Bloody” Catholic queen.

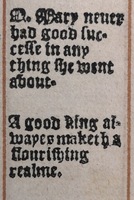

Foxe also writes “Q[ueen] Mary never had good successe in any thing she went about” and “A good king always maketh a flourishing realme.” At one point he simply writes “An abomonition to all Christian rulers,” making it clear that he has dropped the thin pretense of respecting the deceased queen. These marginalia notes are indicative of how Foxe expected his readers to view the queen; Foxe was secure in his belief that any reader who had made it this far in the book would share the same mindset and opinion of Mary, allowing him to write his true thoughts.

It is significant to note that these are merely a few examples of the caustic marginalia Foxe wrote about Mary, although they are symptomatic of the overall tone of the remaining marginalia notes. Towards the end of her life and the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign, Foxe wrote freely about his opinion of the “Bloody” queen and her Catholic beliefs.

Mary and Elizabeth - Silence Speaks Louder Than Words

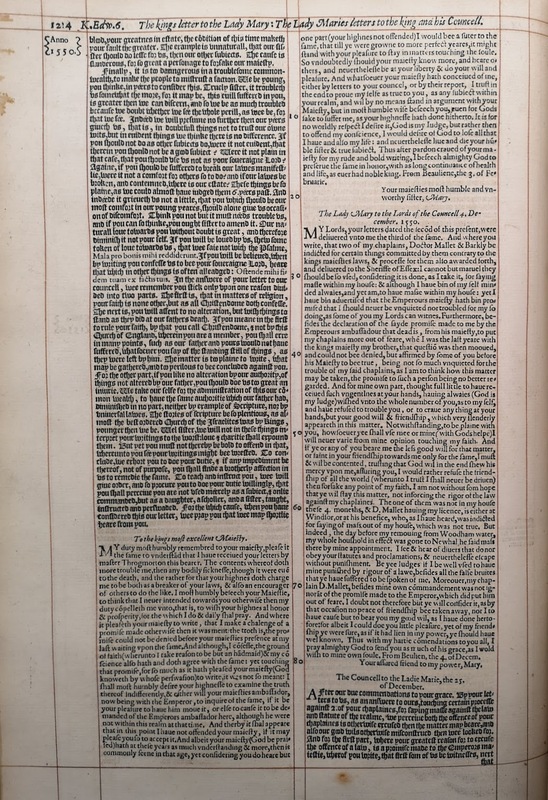

This plethora of marginalia is a marked difference from the first time Mary Tudor is introduced in Foxe’s text. Indeed, the first page the Lady Mary makes an appearance (1214) has a distinct lack of marginalia. The page contains Mary’s letter to King Edward VI and another letter to the Lords of Council and the beginning of their response. Beyond the typical year marker in the upper left corner of the page, however, the margins remain blank. This starkness is heavily contrasted by the marginalia seen on the page containing the first mention of Lady Elizabeth (1896).

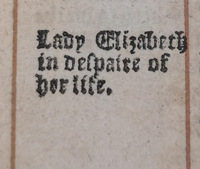

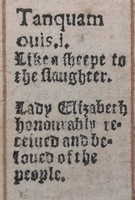

As seen here, the page is riddled with marginalia and annotations pertaining to the main text on Elizabeth. Even the page heading reads “Gods providence in preserving Lady Elizabeth in Queene Maries time,” which, when compared to “The kings letter to the Lady Mary: The Lady Maries letters to the king and his Coucell,” it demonstrates a clear bias for Elizabeth. Mary’s page heading focuses solely on the letters being exchanged while Elizabeth’s heading showcases both her struggle and God’s unwavering support for her.

Although Foxe says nothing explicitly (as contrasted to the end of his book when his marginalia leaves no room for doubt about how he wanted his readers to view Mary and Elizabeth) it is clear that he is setting the stage for how he will interact both women in the upcoming pages. Mary is treated with cool indifference, not even garnering the attention of marginalia during her entrance upon the stage of Foxe’s work. Elizabeth, however, is greeted with a riot of marginalia and blessings, solemn proclamations of God’s favour for the young woman and, more importantly, Foxe’s favour of the Protestant Queen.

The Death of Queen Mary

Foxe does not dwell upon the end of the Catholic queen, instead preferring to mark her passing in a simple side-note on Queen Elizabeth’s crowning. It may seem an odd contrast to the sheer amount of chastising and condemning marginalia Foxe had previously devoted to Mary’s reign, but when viewed in conjunction to Mary’s entrance in the book, her exit appears fitting.

The only other piece of marginalia that mentions Mary’s death appears a little later on when Foxe writes “Lady Elizabeth proclaimed queene the same day that queene Mary died. The Lord make England thankfull to him for his great benefites.” Mary became an afterthought, present only in juxtaposition to the newly crowned Elizabeth.

This change in marginalia output demonstrates the end of Foxe drawing the reader's attention to the differences between the two women – specifically Mary’s shortcomings and Elizabeth’s accomplishments. At one point in the text he had gone as far as to literally write “Comparison between the raigne of Q[ueen] Mary and Q[een] Elizabeth,” in which he highlighted the superiority of Elizabeth’s Protestant reign in comparison to Mary’s Catholic reign.

Now, however, Foxe redesigned his marginalia to guide the reader’s thoughts away from Mary and to instead focus on Elizabeth alone. Acts and Monuments, he decided, had devoted enough pages and marginalia to Mary’s atrocities. Now it was time to reflect and celebrate Elizabeth.

As this page is about the Catholic Queen Mary, it will not contain information solely about Queen Elizabeth separate from Mary. However, I would be remiss not to include a few examples of the marginalia John Foxe wrote about Elizabeth both before and during her reign to truly demonstrate the difference of attitude Foxe held for both Queens.

It is clear from these examples that Foxe was utilizing his marginalia to place both the people and God on Elizabeth’s side. Nearly every mention of Elizabeth is designed to either evoke an empathetic response from the reader or to showcase her faith and the favour of God. While further study needs to be done on the marginalia of Queen Elizabeth in this edition, from this preliminary showcase it can be seen that there is significant manipulation of readers occurring in the margins, just as with Mary’s and Jane’s marginalia.