Reviving Sappho

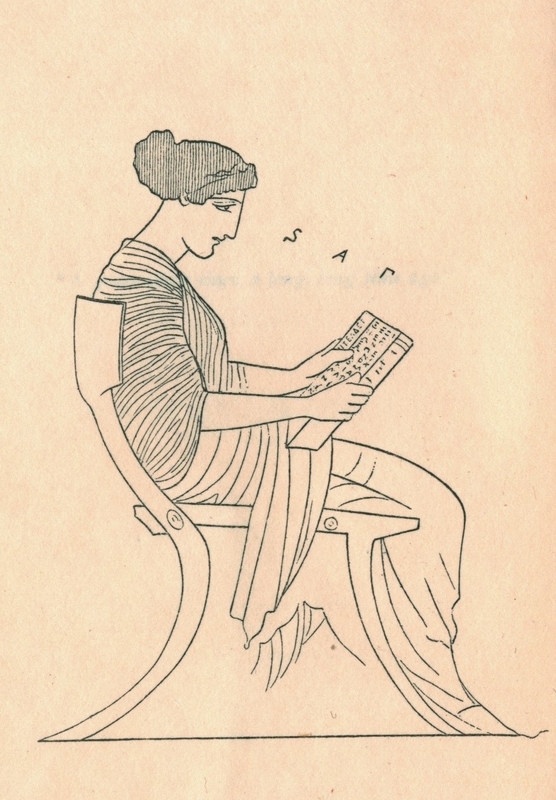

Just as the book traces in Long Ago gesture to the passage of time, so too do its textual contents. In particular, Long Ago references ancient Greece through typographical, aesthetic, and textual components. By reviving Sappho’s lyrics, the Fields participate in a literary tradition that is thousands of years old. Rather than seeking to modernize Sappho’s lyrics, the format of Long Ago celebrates antiquity by using roman numerals for poem titles, placing snippets of Sappho’s lyrics in the original Greek before each poem, and including a frontispiece illustration (pictured on the left) “reproduced from a figure of Sappho … in the museum at Athens” (Long Ago “Note” n.p.). Even the book’s title—Long Ago—signals this awareness and sentimentalization of the past and of time itself.

In her book Victorian Sappho, Yopie Prins writes that Sappho is “a figure produced by literary history” just as much as she was actually a historical figure and writer (52). By way of translation and interpretation, her work has endured centuries of renewal and revitalization. Prins suggests that we can think of Sappho as a figure whose identity is being constantly constructed, reshaped, and transformed by each generation that revisits her work: “Sappho lives on beyond death, but only in translation” (Prins 40). In the nineteenth century, translations and imitations of Sappho increased in number (Prins 3). Field acquired an interest in Sappho after they read a popular translation of her poems by Henry Thornton Wharton, which they explicitly acknowledge in their note to Long Ago. Sappho, a poet from the island of Lesbos who lived in seventh and sixth centuries BCE, is still well-known today despite her surviving work being extremely fragmented and incomplete. However, Sappho’s fragmented corpus did not deter Victorians from continuing to translate her work.

Field’s Long Ago is one such example of Sappho’s literary afterlife. In our twenty-first century moment, many think of Sappho as the first woman poet in the Western literary canon. She is also frequently associated with lesbianism because of her lyrical representations of love between women. The word lesbian comes from Lesbos, the Greek island on which Sappho lived. Indeed, the word sapphic also stems directly from Sappho’s name in our collective imagination of her identity as a lesbian poet. Field’s interest in Sappho coincides with the rise of Victorian Hellenism, a revived interest in ancient Greek culture and history. Prins notes that by the end of the nineteenth century, there were “established associations between Hellenism and homosexuality,” an intersection explored by the Fields under their male pseudonymous authorship (77). Prins also argues that Field’s imitations of Sappho adapt this cultural interest in Hellenism to explore lesbian writing. At the time that Field was writing, categorizations of sexuality were in flux; language that we are familiar with now to describe different forms of queerness (such as “lesbian” and, now somewhat dated, “homosexual”) were only beginning to form. As Prins writes, the term lesbian was beginning to take shape as a social category in the late nineteenth century. Perhaps this is one reason that the Fields, themselves lovers, felt drawn to Sappho’s writing.

The ongoing translation and re-translation of Sappho positions transformation and remediation as a key considerations for the poems within Long Ago. Even this 1897 edition of Long Ago is itself a remediation; the first printing of Long Ago, which was published in 1889 and has a few subtle differences from the 1897 publication. Notably, the 1889 edition printed Greek text in gold, a typographical distinction that visually separates the original writing from Fields’ poems and emphasizes that these poems are translations, and thus, words that have transformed into a new shape and historical context. These typographical details also convey an interest in the construction of words that evidences Prins’s idea that Sappho’s identity has been (re)constructed. It is within this idea of constructed identity that Sappho exists in the pages of Long Ago, much like the Field’s own manufactured authorial persona.

"They plaited garlands in their time;

They knew the joy of youth's sweet prime,

Quick breath and rapture:

Theirs was the violet-weaving bliss,

And theirs the white, wreathed brow to kiss,

Kiss, and recapture."

- "I." Michael Field, Long Ago, p. xi.

Many of Field’s poems in Long Ago explore the concept of time. Scholars of Michael Field have taken interest in the duo’s writing about/from Sappho, and many of these scholars identify the Field’s poetic interest in time and materiality. Mayron Estefan Cantillo Lucuara, for instance, writes that “the metaphysical revision that the Fields formulate in Long Ago disrupts the hegemonic politics of sexual orientation” (219). The poem excerpted above (“I”) illustrates the attention to materiality and time that I have argued is crucial to this book as a physical object. The quoted stanza references time by mentioning “youth’s sweet prime,” a phrase that points to aging as a marker of the time passing and how the body is the site of transformation caused by time. Field also uses anaphora to create a sense of time’s repetition and cyclicality: each of the poem’s three stanzas begins with “they plaited garlands.” In the third stanza, the speaker also remarks that “once in their time, they trod / A choric measure.” These lines look towards the past, creating the sense of time passing through formal strategies such as anaphora and writing in the past-tense. Several other poems in Long Ago explore the concept of time. Poem “VI” depicts time as “eternal” and “immortal” while the speaker in poem “XXII” laments that “Now I am growing old” and in poem “XXXIX,” the speaker suggests that memory is “everlasting.” The repetition of this theme throughout the book explores the effect of time on the physical.

Home Page ֍ Book Traces ֍ Reviving Sappho ֍ Provenance and Production ֍ About ֍ Works Cited