The Yellow Book and Vernon Lee in Context

In Victorian Britain, as higher percentages of the population became literate and educated and books became cheaper to produce, “book publishing became a mass market business” (Weedon 1), causing books’ circulation numbers to skyrocket. The Victorian print market was saturated with periodicals, three-volume novels, and newspapers of all kinds. This market enabled Victorians to access print materials relatively cheaply and quickly and to find materials for any interest, from poetry to news to comedy. However, this market also reflected cultural values of the time, and publishers could receive harsh criticism for publishing works deemed obscene or immoral by the public. Of course, writers and publishers found ways around regulations and cultural values through coded writing.

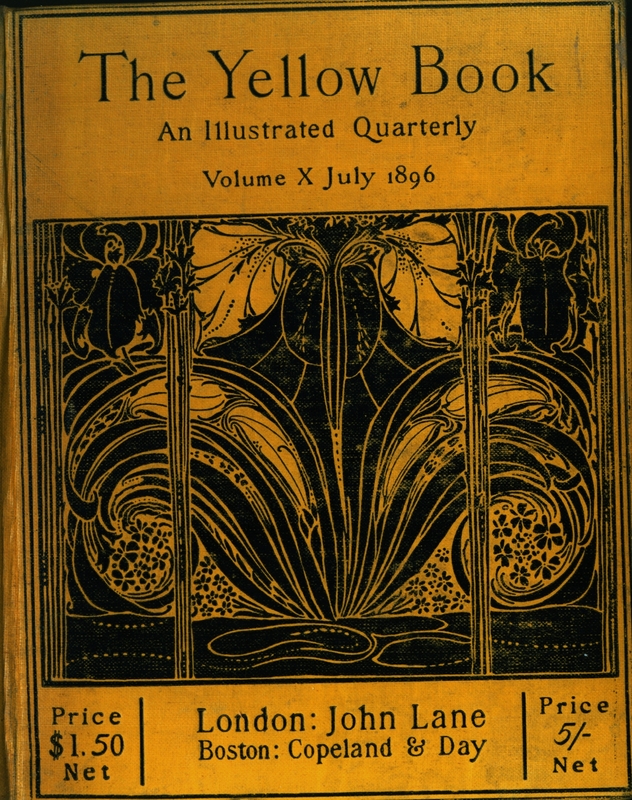

The best example of this phenomenon is perhaps the infamous The Yellow Book periodical, in print from 1894 to 1897. The Yellow Book published quarterly for a total of thirteen volumes and sold for 5 shillings, “well within the means of middle-class buyers—costing more than a monthly review, to be sure, but less than a one-volume novel” (Kooistra). The periodical included fiction, poetry, essays, and stand-alone art. In Victorian periodicals, illustrations typically accompanied works of literature, but The Yellow Book’s inclusion of stand-alone art “was meant to redress the imbalance between the literary and graphic arts” (Dowling 119). The Yellow Book’s bright yellow cover references yellow-back novels, a type of cheaply produced book that was marketed as entertainment, often sold at train stations, and widely read. The Yellow Book was also associated with French novels in the nineteenth century, linking the periodical to both French literature and the decadent movement associated with writers such as Charles Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier. Moreover, The Yellow Book shaped a space for writers to disseminate taboo ideas through a coded mode of writing.

In recent years, there has been renewed scholarly interest in The Yellow Book, including the Yellow Nineties project that includes digitized versions of the periodical, scholarly introductions, contemporary reviews, and biographies of its contributors. Lorraine Janzen Kooistra’s introduction to The Yellow Book notes that the “periodical itself has become virtually synonymous with decadence.” From its bright, bold cover to its allusions to denounced literary movements, The Yellow Book occupied a contentious space in the Victorian print market. Its apparent presence in Oscar Wilde’s hands during his first trial created controversy around it (Ledger 5). Sally Ledger notes that this incident “cemented in the cultural imagination of the 1890s an association between The Yellow Book, aestheticism and decadence and, after April and May 1895, homosexuality” because its appearance with Wilde circulated throughout the press (5).

Though this exhibit does not focus on any texts by Wilde or artwork by Aubrey Beardsley, their connections to decadence (and The Yellow Book in particular) make these figures essential to understanding the reputation and reception of The Yellow Book. Oscar Wilde’s shadow looms large behind this exhibit because of his prominence as a queer figure in the 1890s and the public spectacle of his 1895 trials. Penning controversial works that tested the boundaries of same-sex desire and editing periodicals such as Woman’s World, Wilde was a key queer figure in the literary context of the fin de siècle.

Wilde’s eventual conviction on the charge of gross indecency began with his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas. Both Wilde and Douglas used literary venues to discuss queerness and gain understanding and empathy from readers. As Wilde biographer Richard Ellman describes, during his undergraduate degree at Oxford, Douglas “took over the editorship of an Oxford literary magazine called the Spirit Lamp, and remade it with the covert purpose of winning acceptance for homosexuality” (Ellman 386). Similarly, Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) implies same-sex romance and desire. Wilde’s writing was so much associated with queerness at the time that Gregory Mackie claims that his “lingering posthumous disgrace had tainted his literary output with a kind of obscenity” to the point that only publishers of pornography were disseminating his work in the early twentieth century (980).

The Yellow Book’s association with queerness celebrates this otherness instead of rejecting or weaponizing it; however, its controversial reputation and affiliation with Wilde meant that it frequently received criticism and condemnation from reviewers. For instance, an 1894 review of The Yellow Book appeared in The Critic under the title “A Yellow Impertinence” and illustrated the periodical’s impression on the print market and public:

The Yellow Book is the Oscar Wilde of periodicals. With enough cleverness to be successful by legitimate methods, Mr. Wilde preferred to attract attention with his long hair and silk-encased calves. It is the same with The Yellow Book. Its contributors and illustrators are clever enough to catch the public attention by serious endeavor, but its editors prefer to attract more sudden attention by mounteback methods. Both [editor] Mr. Harland and [art editor] Mr. Beardsley are young men, and their attitude is as that of one who sticks his tongue in his cheek at the public—and who has a great deal of cheek to stick it in. (“A Yellow Impertinence” 360)

This review evidences the association between Wilde and the periodical through an aesthetic comparison: the review criticizes artifice and appearance, implying that these superficial qualities rob art of its intellect and merit. Yet the review also indicates the periodical’s potentially dangerous connection to the decadent movement, reviled for its celebration of artifice. The review references long hair, silk, cosmetics, and vitriolic humour, suggesting that the magazine, like Wilde, plays with appearances in ways that subvert convention.

Just as Wilde subverts conventions of gender by wearing silk and having long hair, so too does The Yellow Book indulge in rich colour, cheeky illustration, and satirical content. The periodical’s presence in the print market aggravated some readers and reviewers, yet it offered a space for queer writers to explore non-normative expressions of the self. The association with Wilde links The Yellow Book to a marginalized fringe of people who refuse or resist expectations of gender and sexuality expression. This review suggest that The Yellow Book’s contributors go against what is considered “natural” and therefore morally good. By 1890, Wilde had an established reputation of notoriety and controversy. Trevor Fisher writes that Wilde was “the most visible aesthete” of the time and had “developed the ability to scandalize the Respectable” (59). Moreover, he was acquainted with several contributors to The Yellow Book, including Vernon Lee, Aubrey Beardsley, Max Beerbohm, and John Gray.

The Yellow Book defied Victorian expectations of books as intellectual, non-aesthetic objects because of its attention to form and appearance. It included bold, shocking illustrations that emphasize the visual aspect of the periodical and propose the radical notion that materiality matters to the reading experience. While many periodicals used illustrations to supplement textual contributions, The Yellow Book includes stand-alone art pieces. Leah Price describes the flippant attitudes of Victorians towards the aesthetic value of books, writing that to Victorians, “the language of insides and outsides makes any consciousness of the book’s material qualities signify moral shallowness” (3). Price’s observations link what she calls reading, handling, and circulating to Victorians’ physical experience of books (5). Price’s analysis suggests that Victorians viewed any celebration of aesthetic value in print form to be superficial and to detract from the intellectual value of the text contained within book. Moreover, Price’s argument suggests that the attitudes surrounding books themselves were heavily moralized; the appearance of one’s book could garner judgment about one’s moral character and beliefs. By the end of the nineteenth century, these attitudes began to shift with the emergence of periodicals like The Yellow Book that challenged readers’ expectations of print aesthetics.

The Decadent Movement

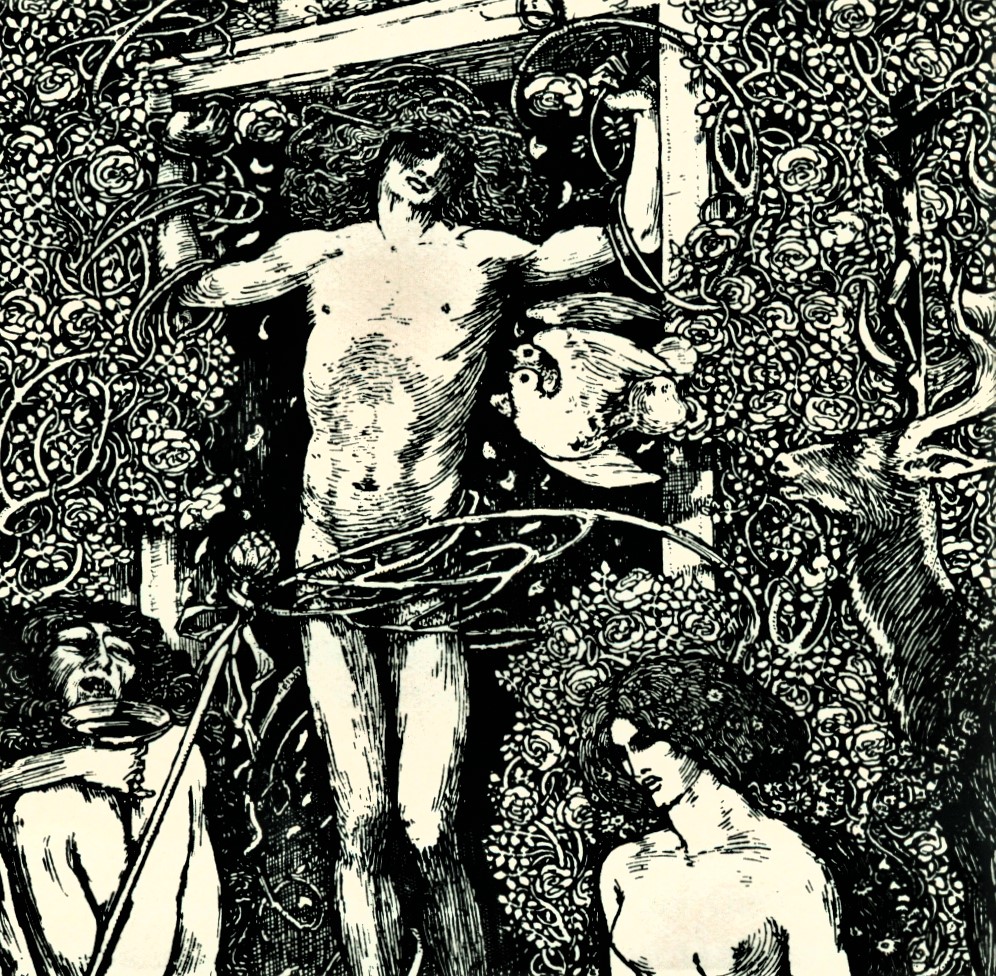

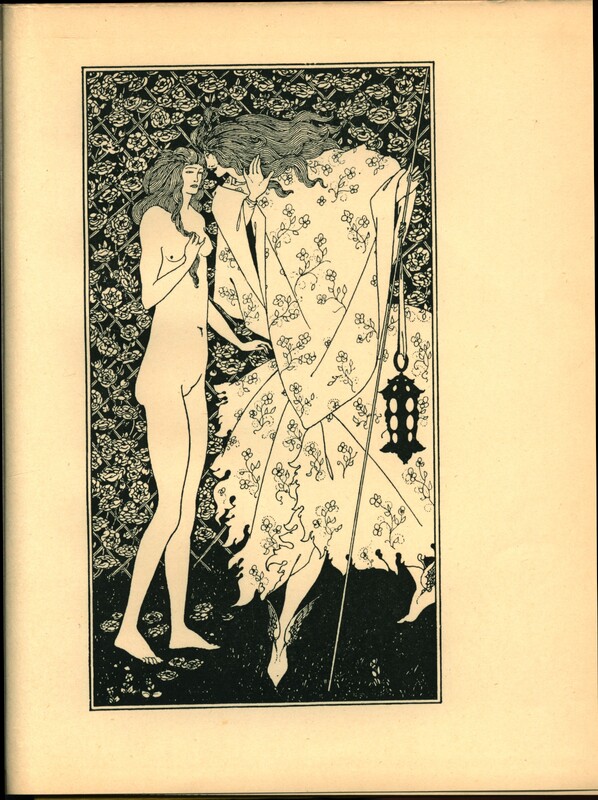

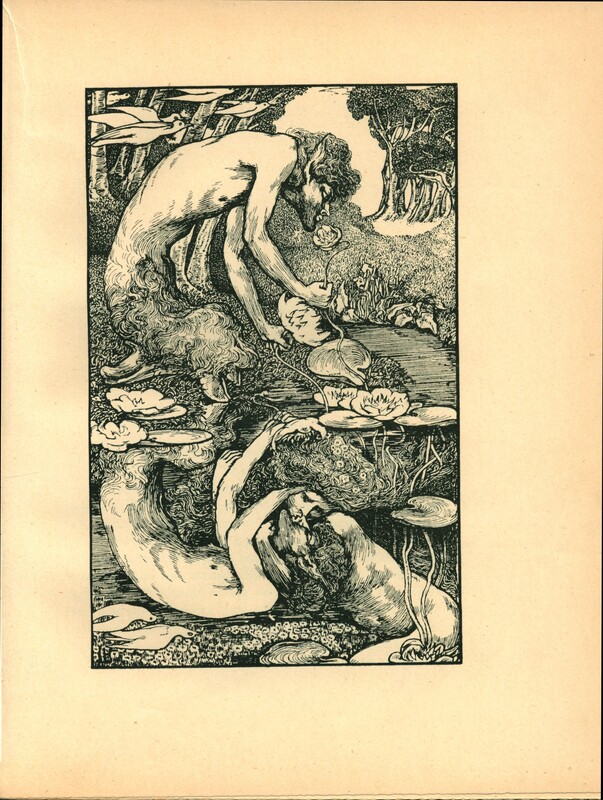

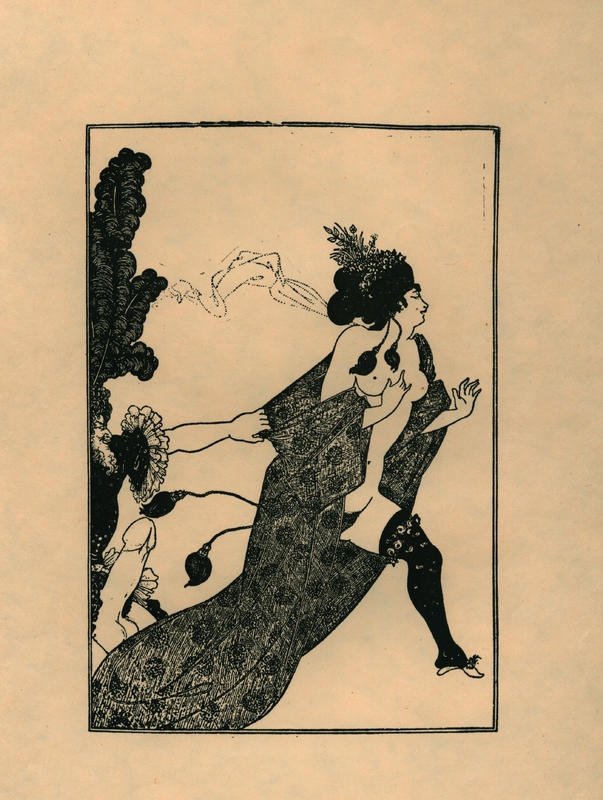

The decadent movement celebrated artifice, satire, and excess in ways that went against the grain of conventional nineteenth-century attitudes that valued tradition, respectability, and natural order and devalued aesthetic beauty as a superficial quality. Decadent art, by contrast, celebrated absurdity, artifice, excess, and beauty. In The Yellow Book, many illustrations promulgate these sentiments. Figure 2, “The Mysterious Rose Garden” by Aubrey Beardsley, is one such example. The illustration is saturated with elaborate floral patterns that exemplify the trait of decadent excess, and the two figures appear to be whispering, creating an atmosphere of secrecy and defiance. In figure 3, “The Reflected Faun” by Laurence Housman, the illustration has similarly intricate and decorative patterns. The mythological faun kisses a rose, but his image is reflected in the water as him kissing a woman. This difference in reflection plays with the viewer’s perception of reality and indicates hidden erotic desire. Both illustrations exemplify how decadent art stylistically celebrates excess and exploratory desire in The Yellow Book.

Decadence allows for a deeper exploration of queerness in the nineteenth century by allowing writers and artists to contemplate socially unacceptable desire and question strict attitudes about the expression of gender and sexuality. Joseph Bristow’s historicist reading of decadence suggests that looking to the past made writers ask “how they might modify, rework, and even imagine anew sexual modernity” (“Decadent Historicism” 4). By writing in the tradition of decadence, writers exploited distortion to explore expressions of queerness and criticize accepted attitudes toward subjects considered unmentionable in public forums.

Decadence is often remembered for its French roots, depictions of incestuous lesbianism, and other sexual “perversions” that shocked Victorian readers. By contrast, much of English decadence was subtle, though it nevertheless explored the fringes of sexuality and gender to “find, celebrate, and communicate the beauty of subjects which the conventional majority would find emotionally and morally unacceptable or repulsive” (Maxwell 7). Bristow describes English decadence as having “aesthetic qualities of perversity, disease, and decay” (Introduction 10). As such, decadence was historically rejected and condemned: Alice Kaminsky notes that decadence had a “bad reputation” in the nineteenth century because writers associated with decadence were linked to sexual perversion, excess, artificiality, and the absurd (376-77). This reputation became so pervasive that “by the century's end, people were using the terms ‘decadent’ and ‘aestheticist’ to condemn almost any artwork that displayed innovations in aesthetic philosophy, subject or style” (Denisoff 31). These associations nevertheless tested the limits of the unmentionable and offensive: Karl Beckson writes that one aim of decadence was “its desire to pull down the decaying temples of Victorian respectability” (Introduction xi).

By linking decadence with queerness, I make two interconnected assertions: that decadence is not inherently queer, but that its association with queerness via homophobic assertions of “sexual perversion” and its relation to Oscar Wilde links it to a subversion of heteronormativity. In The Yellow Book, decadence is perhaps best understood by looking at contributions by its early art editor Aubrey Beardsley. Linda Zatlin describes Beardsley’s style as “bawdy drawings with erotic elements that calculatedly shocked middle-class London viewers and scandalized reviewers.” Gregory Mackie echoes Zatlin, affirming that Beardsley had a “reputation for erotica and graphic naughtiness” (60). Zatlin’s description certainly encapsulates this example of Beardsley’s illustrations in figure 4 for a privately printed edition of Aristophanes’s Lysistrata.

However, Beardsley’s illustrations for The Yellow Book demonstrate these same elements of bodily distortion and decadent characteristics more subtly. Beardley’s “L’Education Sentimentale” (figure 5) depicts “an aged prostitute teaching a young girl the tricks of the trade” (Beckson “‘The Yellow Book and Beyond” 403). In “The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes” (figures 6, 7, and 8), Beardsley contorts facial expressions and body proportions to create a sense of artifice, absurdity, and distortion. Though these illustrations are more stylistically minimalist than other decadent art in terms of linework, Beardsley emphasizes the roles of costume and performance to express excess and artifice. Each figure’s clothes have detailed frills, buttons, and feathers, and the central person in figure 8 is holding a mask. This attentiveness to clothing reflects the illustration’s interest in appearance and beauty, unsettling Victorian attitudes about modesty and respectability.

In terms of style, “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” certainly participates in the tradition of decadence by depicting artifice, exploring queer sexuality, and representing aesthetic excess. Much like Beardsley’s illustrations, characters in Lee’s story have bodies that defy conventions of beauty or they don elaborate costumes that produce a sense of artifice. For instance, the Snake Lady Oriana occupies a body that takes on multiple forms that transcend age, gender, and even species. Another character who personifies decadence—particularly the characteristic of artifice—is the Duke, whose face young Alberic sees being “plastered with a variety of brilliant colours” that maintain the illusion of his youth (Lee 297). These examples demonstrate Lee’s participation in the decadent movement and its influence on “Prince Alberic.”

Behind the Type: Vernon Lee (Violet Paget)

Vernon Lee (1856-1935), the pen name of Violet Paget, was a prolific writer of fiction, travel writing, and essays, including “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady.” Even as “Lee distanced herself from what she saw as the excesses of late-Victorian aestheticism,” as Patricia Pulham writes, she continually engages with its it throughout her literary career. Kristin Mahoney explains that Lee would continue to reference the “language of late Victorian aestheticism and decadence to speak to the problems of the modern moment” as she continued to write in the early twentieth century (60). Despite her prolific publication history, Lee’s “Prince Alberic” is her only contribution to The Yellow Book.

Though she was born as Violet Paget, Vernon Lee adopted her pseudonym once she began publishing her work and also used the androgynous pen name within her personal correspondence—often interchangeably with her birth name (see Vernon Lee letters). It was common for women writers in the nineteenth century to use male or androgynous pseudonyms; for instance, the major Victorian writer Mary Ann Evans (author of Middlemarch and Adam Bede) published as George Eliot. However, Lee’s use of the pseudonym in her everyday life suggests that the ambiguity of her persona extended beyond the benefits it afforded her within the world of publishing and perhaps suited her vision of her own gender identity.

Lee is now considered by scholars to be a proto-lesbian writer, though the term lesbian was only beginning to be theorized by medical practitioners thinking about same-sex desire at the time that she wrote. Throughout her lifetime, she had intimate, romantic, and intensely emotional relationships with writers Mary Robinson, Clementina Anstruther-Thomson, and Amy Levy. For instance, when Mary Robinson became engaged to James Darmesteter, Lee “suffered a major physical and mental collapse” (Brown). In Vernon Lee: A Literary Biography, Vineta Colby points out that “Vernon Lee and Mary Robinson ‘might serve as a possible case-history for the section on Lesbianism in [Havelock Ellis’s] Sexual Inversion’” (Phyllis Grosskurth qtd. in Colby 51).

Yet Lee deliberately curated an ambiguous gender identity in her writing as well as in her appearance and personality. Colby describes Lee as having “mannish attire—dark, severely tailored dresses, high starched collars, stiff bowler or boater hats. But these were fashionable in the ’80s and ’90s.… But less acceptable in society was her strong personality. Talkative, argumentative, dogmatic, she insisted on dominating conversations” (52). Lee’s subversive gender expression, “unfeminine” personality, and queer romantic desire parallel the coded discourse about queerness in “Prince Alberic.” Though indirect, Lee’s modes of expression subvert expectations of gender and initiate discourse about taboo topics.

Scholarship in the last few decades has struggled to define Lee’s sexuality and queerness. Vineta Colby’s biography of Lee insists that her relationships with women were hardly more than romantic friendships while Catherine Maxwell and Patricia Pulham suggest that this framing of Lee’s sexuality is a “sanitizing strategy” (3). In another study on Lee, Christina Zorn remarks that criticism on Lee “reveals the historical limitations of any approach based on too narrow definitions of sexual identity” (23). Indeed, Lee’s queerness is often minimized because there is little evidence that Lee’s relationships were physically intimate. Irene Cooper Willis (Lee’s executor), for instance, claims that “‘Vernon was homosexual but she never faced up to sexual facts … She has a whole series of passions for women, but they were all perfectly correct. Physical contact she shunned’” (Willis qtd. in Maxwell 4). This reasoning, however, falsely presumes that sexual experience legitimizes sexual identity. Sally Newman similarly notes that scholarship on Lee consistently “describe[s] her as a ‘failed lesbian’” and attempts to “‘prove’ lesbian existence” (55). More recently, scholarship on Lee accepts ambiguity about her sexuality. Dustin Friedman posits that Lee “construct[ed] histories of lesbianism that articulate an autonomous, but not essentialist, sense of queer selfhood for women” (25). Despite the debates about her sexuality, the scholarly work on Lee that I have summarized in this section demonstrates how her story’s publication in The Yellow Book challenged expectations of gender and sexuality at the end of the nineteenth century and even within scholarly discourse to this day.