“Like a thorn in his flesh”: Celebrating Queer Desire in “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”

Modern readers of Victorian texts may associate Victorians with prudishness, flowery prose, and conservatism, but this exhibit aims to provide context for art that went against the grain and offered controversial celebrations of queerness or critiques of heteronormativity within Victorian culture. These materials unsettle conceptions of Victorians as stuffy, traditional, and rigid.

Scholarship in the last century has revisited these stereotypes and argued that Victorians did talk about sexuality. Emma Liggins observes that “same-sex desire was beginning to be signalled in coded ways in late-Victorian texts” (38). By disguising discourse about queerness as fiction, writers could explore non-normative desire. Steven Marcus popularized the idea that the Victorians did discuss sexuality by surveying Victorian pornography and other materials about sexuality (such as medical texts) in his book The Other Victorians (1966). Thus, censorship, taboo, and restriction constitute part of Victorian discourses about sexuality.

Indeed, Vernon Lee demonstrates how fiction can depict queer sexuality, even when it is disguised or concealed within the text. This exhibit’s analysis explores these ideas through Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” and its place in The Yellow Book to demonstrate how Lee’s story and The Yellow Book disrupt conventions about gender and sexuality in the fin-de-siècle print market. My three-part analysis argues that “Prince Alberic” celebrates queer desire and non-normative bodies and demonstrates the harm done by social expectations to conform to heterosexuality through marriage.

“Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” appears in volume 10 of The Yellow Book (1896). The story plays with the genre of the fairy tale, yet its allusions and plot have implications for the real world. Set in the late 1600s up to 1701, “Prince Alberic” is largely concerned with art as an escape from social pressures to get married, this escape being exemplified through the tapestry of the Snake Lady with which Alberic is enamoured. The process of desire is one of discovery through the tapestry depicting the Snake Lady. “Prince Alberic” uses art as a conduit for queerness by establishing the tapestry as an object of desire and aesthetic magnificence within the magical world of the story.

The tapestry, Alberic’s sole interest and obsession, is a representation of one of Alberic’s ancestors, Alberic the Blond, and a woman named Snake Lady Oriana: “a knight had reined in his big white horse, and was putting one arm round the shoulder of a lady, who was leaning against the horse’s flank” (293). Alberic is infatuated with the tapestry from an early age, preferring to stare at it for hours instead of at the bland landscape of his home at the Red Palace of Luna. Alberic refuses food when his uncle, the vain and short-tempered Duke Balthasar Maria, orders the tapestry to be removed and replaced with one that he prefers. In protest, Alberic cuts up the new tapestry with a kitchen knife. The Duke punishes Alberic by sending him to the Castle of Sparkling Waters, belonging to his ancestor Alberic the Blond, where Alberic befriends a garden snake and an old woman who calls herself his Godmother, with whom he develops deep friendships.

Years pass at the Castle and Alberic thinks about the tapestry “more than ever” (315) as he ages, finding that the Castle resembles the tapestry so closely that he feels that “the tapestry has become the whole world” (301). His interest in the tapestry is all-consuming and baffling to the rest of the Palace who find the depiction of the half-serpent Oriana repulsive and abhorrent. Alberic eventually convinces a passing storyteller and a priest to tell him the full story of his ancestors Alberic the Blond and Marquis Alberic. He learns that Oriana, trapped in the form of a snake, can only be permanently transformed into a human if a suitor kisses her three times and remains faithful to her for ten years; both Alberic the Blond and Marquis Alberic failed to remain faithful. As the story goes, Oriana can only be destroyed if her head is severed from her body.

This story only increases Alberic’s interest in the tapestry, and he awakens one night to find the garden snake outside. He kisses the serpent and falls unconscious, later waking up in the lap of his Godmother. At this time, the Duke realizes that Alberic is the next in line to rule the Palace, and he is now of marriageable age. He orders Alberic back to the Red Palace, but Alberic has no interest in anything save for his snake. When the Palace faces bankruptcy, the Duke realizes that Alberic’s marriage to a wealthy princess is the only hope for the Palace, but Alberic repeatedly refuses to marry.

Frustrated by Alberic’s obstinacy, the Duke sends Alberic to the state prison, where he stays for several weeks until the Duke visits the prison with his councillors, the Jester, Dwarf, and Jesuit. During the visit, the Duke spots Alberic’s snake on the ground. The Jester and Dwarf stab the snake while Alberic is restrained by the Jesuit, and the snake, its head severed, dies. Alberic dies two weeks later after refusing to eat, and rumours circulate that when his cell was cleaned, a woman’s severely injured corpse was found in place of the snake’s body.

Scholar Margaret Stetz asserts that “Prince Alberic” is “as much a political allegory as a fairy tale” (113). Her reading of “Prince Alberic” tracks references to the writing of Oscar Wilde, who had been incarcerated in 1895, one year before “Prince Alberic” appeared in The Yellow Book. Stetz’s article provides an important starting point for my analysis of the text because her argument suggests that the story directly responds to current controversy and offers radical commentary on non-normative desire. Stetz observes that Lee uses “readily identifiable Wildean literary tropes throughout” (113), including its fictional historical setting, rich aesthetic prose, and lunar and bird imagery. These similarities solidify the links among text, periodical, and print market; to support Wilde so explicitly in this cultural moment was a bold defiance of heteronormativity and the status quo. With an awareness of the story’s connection to Wilde, I propose building on Stetz’s reading by demonstrating how the story reclaims decadence and subverts the homophobic connotations of decadence among mainstream reviewers and the public through a celebration of queerness.

Alberic’s queer desire is revealed through his intense attraction to the tapestry, which acts as an escape from the monotony of the Red Palace. Indeed, the story introduces Alberic after the Duke decides to remove the tapestry from his room. The Duke regards the tapestry as “old and Gothic,” wishing to remove it from the room with the reasoning of “dislik[ing] snakes … and [being] afraid of the devil” (290). Balthasar’s association with snakes and the devil recalls the biblical story of Adam and Eve in which a snake tempts Eve into sin, linking the tapestry with biblical sin and temptation. The figure of the Snake Lady represents desire, temptation, and sin along with aesthetic beauty. Balthasar replaces the tapestry with one that depicts the biblical story of Susanna and the Elders, which portrays a woman who refuses to provide sexual favours to two men after they spy on her. Upon noticing the absence of the Snake Lady tapestry, Alberic “cut Susanna and the Elders into strips with a knife he had stolen out of the ducal kitchens … and refused to touch his food for three days” (290).

Alberic’s severe reaction reveals his deep connection to the Snake Lady tapestry, which he regards as a source of “inexhaustible charm” (291). Alberic’s interest in the tapestry extends far beyond simple charm as he begins to view the world through the perspective of the tapestry. The tapestry is decorated with an abundance of plants, such as lilies, poppies, and hazelnuts, and animals that Alberic has never seen outside of art, such as birds, butterflies, squirrels, and rabbits (291). Entranced by these creatures, Alberic “spend[s] much ingenuity seeking for them in the palace gardens” but finds that “there were no live creatures there except snails and toads, which the gardeners killed” (291). Alberic can only access the vibrance, variety, and wonder of life through art. Alberic’s curiosity about these creatures illuminates his desire for something beyond what his palace offers—something he can access only through this specific piece of art. When Alberic finally sees a rabbit—“the most fascinating of the inhabitants of the tapestry border” (291)—in the Palace, it is skinned and dead in the kitchen. Alberic becomes “satisfied with seeing the plants and animals in the tapestry” rather than in reality, a satisfaction that signifies the tapestry’s role as an outlet for desire (291). Through art, Alberic can access a different version of his world in which his desires and views exist and are celebrated.

Because the tapestry is so intricate, Alberic discovers each of its sections gradually over time, beginning with the border of plants and animals before noticing the figures in the middle. He doesn’t notice the middle of the tapestry for some time because it is “worn and discoloured” and difficult to see without direct light (292). When Alberic finally notices the middle of the tapestry, he sees a knight and a beautiful woman. Initially, the two figures seem to conform to conventions of a heteronormative pair, being a knight and a beautiful lady. However, Alberic can see only the top halves of the two figures because their lower bodies are obscured by a crucifix on top of a heavy dresser covering part of the tapestry. The symbolism of the crucifix echoes the burden of religion upon Alberic’s desires, suggesting that social expectations have worked to hide Alberic’s true desires from him. Because the tapestry is obscured, the discovery of Oriana’s full form is an exploratory process fuelled by interest and desire. Alberic is driven by curiosity and pleasure and is scolded for any interest he shows in the tapestry by others in the palace. This process of discovery occurs as Alberic transitions from childhood into adolescence, representing his journey of sexual discovery much like a coming-of-age narrative.

However, despite his obsession with the tapestry, Alberic finds that it is “impossible even to mention Alberic the Blond and the Snake Lady” to anyone (Lee 313). He perhaps senses the stigma around his interest in tapestry, first hinted at with the Duke’s revulsion towards it and removal of it. Thus, Alberic faces “inexplicable shyness, almost a dread, of knowing more on subjects which are uppermost in [his] thoughts” (311). Though Alberic cannot explicitly name this feeling, his sense of dread indicates his awareness that the desire and curiosity he is experiencing are unconventional and socially condemned.

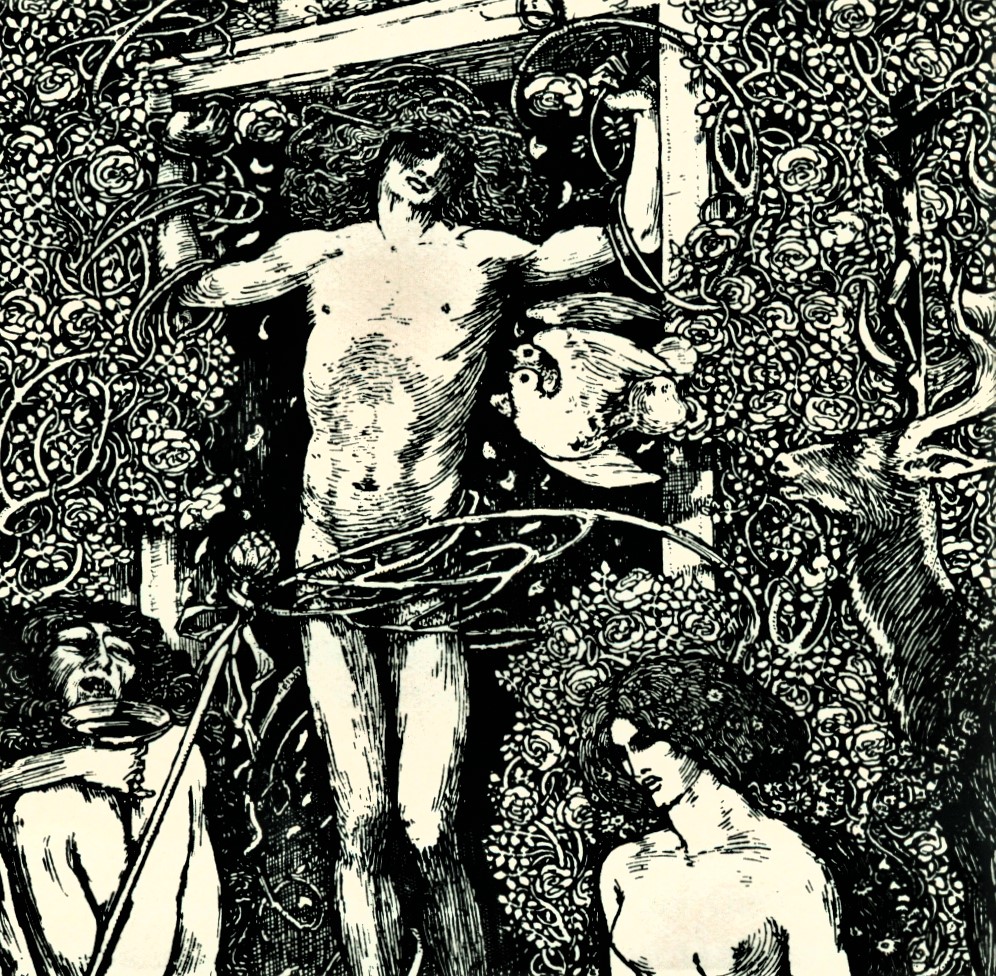

When finally an attendant shifts the dresser to another room, Alberic can see Oriana in full:

For where the big crucifix had stood, the lower part of the beautiful pale lady with the gold thread hair was now exposed. But instead of a skirt, she ended off in a big snake’s tail, with scales of still most vivid (the tapestry not having faded there) green and gold. (Lee 294)

This revelation of Oriana’s hybrid form constitutes an instance of bodily otherness and again references the biblical story of Adam and Eve. Her serpentine form associates her with temptation, desire, and the forbidden because of Alberic’s interest in her. Notably, the coloured fabric of her scales has not faded like the rest of the tapestry, revealing the beauty and thrill about her body from Alberic’s perspective. Alberic’s reaction to Oriana’s full form is “violent excitement,” indicating that his desire and interest in the tapestry have increased with this revelation (294).

The diction in this short quotation signals an intensity of emotion to the point of eroticism. Oriana’s deviation in physical form subverts the understanding of what a beautiful woman is by representing Alberic’s perspective. Where Victorian audiences would expect a skirt, Oriana has an unclothed lower body that is magical and non-human. Dustin Friedman reads this scene as demonstrating “how encounters with art could be crucial for gaining sexual self-knowledge and, in turn, how queer desire could bring into being radically new ways of perceiving the self and the world in and through art” (2). As Friedman suggests, the full tapestry transforms Alberic, whose excitement and interest in the tapestry is palpable.

The representation of Oriana’s body disrupts Victorian conventions of beauty and propriety. The depiction of Oriana as beautiful not in spite of but because of her difference is a celebration of queerness, even if those around Alberic disagree. Oriana’s magical half-serpent form allows Lee to portray non-normative desire indirectly. Emma Liggins theorizes that the “fin-de-siècle woman’s ghost story, the spectral encounter … can function as the longed-for erotic moment which makes amends for the sterility and boredom of marriage/social convention” (38). Alberic’s reaction supports Liggins’s point as he is wildly excited by the reveal of Oriana’s lower half, enamoured with her novelty in contrast to the conventionality of the Red Palace.

Alberic later describes his obsession with the tapestry—and, by extension, his desire for the Snake Lady—as curiosity “like a thorn in his flesh, working its way in and in; and it seemed something almost more than curiosity” (315). This quotation figures Alberic’s desire as the prick of a thorn, evoking erotic phallic imagery that indicates that his curiosity about the tapestry is more complex than simple interest. Rather, it is the beginning of his queer awakening.