Decadent Desire and Queer Victorians: A Digital Exhibit

Though public celebrations of queer pride are relatively new phenomena, queer writers have for centuries been covertly authoring literatures that celebrate and record queer perspectives. Because fiction is ostensibly make-believe, it offers authors a forum to covertly discuss queerness and challenge ideas about gender and sexuality indirectly. Though many writers still faced harsh scrutiny and criticism for their work, others were able to avoid the consequences of explicitly engaging with these controversial subjects in their charged historical moments.

This exhibit examines writing from the late nineteenth century, a period that many today associate with ultra-conservative values, religious morality, modesty, and strict adherence to social etiquette. Despite this modern reputation, the nineteenth century witnessed considerable discourse around topics of sexuality and gender, especially as these were represented in literature. Some queer writers from the Victorian period (1837-1901), such as Oscar Wilde, have attained a lasting reputation in the public mind for their literary accomplishments (and scandals!), while most have been forgotten to all but those with an interest in this time period or with training and education in nineteenth-century literature. However, the flourishing of queer studies within the humanities over the last three decades has led to scholars reclaiming many of these forgotten voices and re-examining their impact on Victorian audiences in both literary criticism and newer digital projects such as the Yellow Nineties.

This exhibit follows in the footsteps of these scholars, exploring the importance of these materials in a digital format with a general, non-specialist audience. I have chosen the materials in this exhibit based on the collections available at the University of Victoria’s Special Collections. In particular, this exhibit discusses how certain nineteenth-century periodicals and texts not only challenged contemporary conventions of gender and sexuality but also explored and celebrated queerness.

The main text I present is Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” (1896) in the context of its initial publication in the periodical The Yellow Book (in print from 1894 to 1897) and the impact of “Prince Alberic” on the Victorian print market and public. In this exhibit, I propose that Lee’s text and The Yellow Book disrupt the mainstream print market by occupying literary and artistic space with subversive content. The Yellow Book provided a tangible forum for Lee’s “Prince Alberic” that fostered indirect discussion of queer identity through representations of non-normative desire and self-expression, thereby claiming queer identity by embodying characteristics of the decadent movement.

In this exbibit, I use the term “queer” to describe varying experiences of gender and sexuality, but my terminology requires a note of explanation about this choice. Queer as a word and queerness a field of study are both modern understandings of sexuality and gender that were not used in the nineteenth century. However, the field of sexology—the scientific study of human sexuality—arose in the late nineteenth century with works such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) and Havelock Ellis’s Sexual Inversion (1897). These works began to develop theories, categorizations, and terminology about sexuality.

The widespread Victorian conception that any type of sexuality that is not heterosexual is morally wrong—and even a type of disease or illness—suggests fear and anxiety about non-normative types of human sexuality. Moreover, queerness was often linked to attributes like perversion, excess, and immorality—and these accusations extended into the literary realm. Literary and artistic movements such as decadence and aestheticism became synonymous with figures like Oscar Wilde and, by proxy, homosexuality.

Queerness as a type of identity, then, is defined by its resistance to dominant, accepted types of gender expression and sexuality. Thus, the term queer describes how something does not conform to social expectations rather than how something holds a stable definition: “queer is contained within, yet residing on the margins of, a heteronormative culture” (Roden 1). Using queer as an umbrella term within this exhibit is useful because it places this project within a broader scholarly conversation (in queer studies and gender studies) about non-normative ways of being in the nineteenth century.

However, this exhibit does not aim to unnecessarily categorize, label, or otherwise attribute specific anachronistic meanings to these texts and historical figures. Rather, I am interested in exploring how queer identities challenged and resisted uniformity and conformity within literary texts and associated and print materials. This exhibit asks questions like How do these stories and publications challenge Victorian conventions of gender and sexuality? How do they resist or complicate categorization to make readers rethink their assumptions of these conventions? By posing such questions, this exhibit aims to connect our modern discussions about queerness to a long history of queer resistance and celebration.

Vernon Lee’s “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” (1896)

The main text that this exhibit showcases is Vernon Lee’s short story “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady,” which was published in a popular yet controversial periodical called The Yellow Book in 1896. “Prince Alberic” is set in the fictional Duchy of Luna in the late 1600s and depicts young Alberic’s infatuation with a magical half-human, half-snake lady depicted in a tapestry, an obsession for which he is chastised. Along with the story’s content and placement in this periodical, I consider the author’s identity as a woman writer using an androgynous pseudonym in both her public and private life and how it informs the narrative; the reputation, publication history, and context surrounding The Yellow Book; and how “Prince Alberic” portrays queer desire and resists the clear categorization of generic conventions, morality, and the human body.

Approaches to literature through the lens of queer theory—a field of study encompassing sexuality and gender studies—have been on the rise since the early 1990s, when landmark works of theory and criticism such as Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990) and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990) were published. This theoretical legacy around sexuality and gender forms an integral framework for my analysis of Vernon Lee’s work. I am certainly not the first scholar to discuss same-sex desire in the late nineteenth century or even the first to discuss it within the confines of The Yellow Book. The critical conversation about The Yellow Book in the last few decades has renewed interest in gender, sexuality, and woman writers.

Scholars who have examined women’s writing in The Yellow Book describe the periodical as an important venue for women to explore desire and attain literary achievement despite most of The Yellow Book’s contributors being male and its discourses largely masculinist. One such scholar is Sally Ledger, who claims that women writers such as Ada Leverson and Olive Custance “used the pages of The Yellow Book to explore and articulate female sexual desire” (21). Laurel Brake has claimed that The Yellow Book had “insistent discourses of gender, with sexual as well as cultural politics,” yet the periodical was “suffused with male discourses of gender” in which women were perceived as the “other” (39-40). Linda Hughes examines how women poets influenced The Yellow Book, established writing careers by publishing within the periodical, and “ignored bourgeois prohibitions on female sexuality” (850). These scholars illustrate the divisive and experimental landscape in which Lee publishes “Prince Alberic.”

As Vineta Colby remarks in her 2003 biography of Lee, “it is a small company who read Vernon Lee today” (xi). Criticism on Lee’s writing that does exist has concentrated on her ghost stories, her place as in the New Woman movement, her travel writing and life in Italy, and her queerness. Few scholars have discussed “Prince Alberic” at length, though it is one of the better known of Lee’s short stories, but of thos few, several scholars have discussed queerness and sexuality in Lee’s “Prince Alberic.” Dustin Friedman theorizes that the Snake Lady “is a figure not just for lesbianism but for any form of desire that departs from cultural norms” (142). Emma Liggins reads “Prince Alberic” through the lens of a spectral encounter, writing that the story is a “comment on the shortcomings of heterosexual marriage and bourgeois life” (37). Martha Vicinus reads the story through the lens of the nineteenth-century adolescent boy as a “handsome liminal creature [who] could absorb and reflect a variety of sexual desires and emotional needs” (91). Finally, Margaret Stetz examines the story as a political allegory for the Oscar Wilde trials.

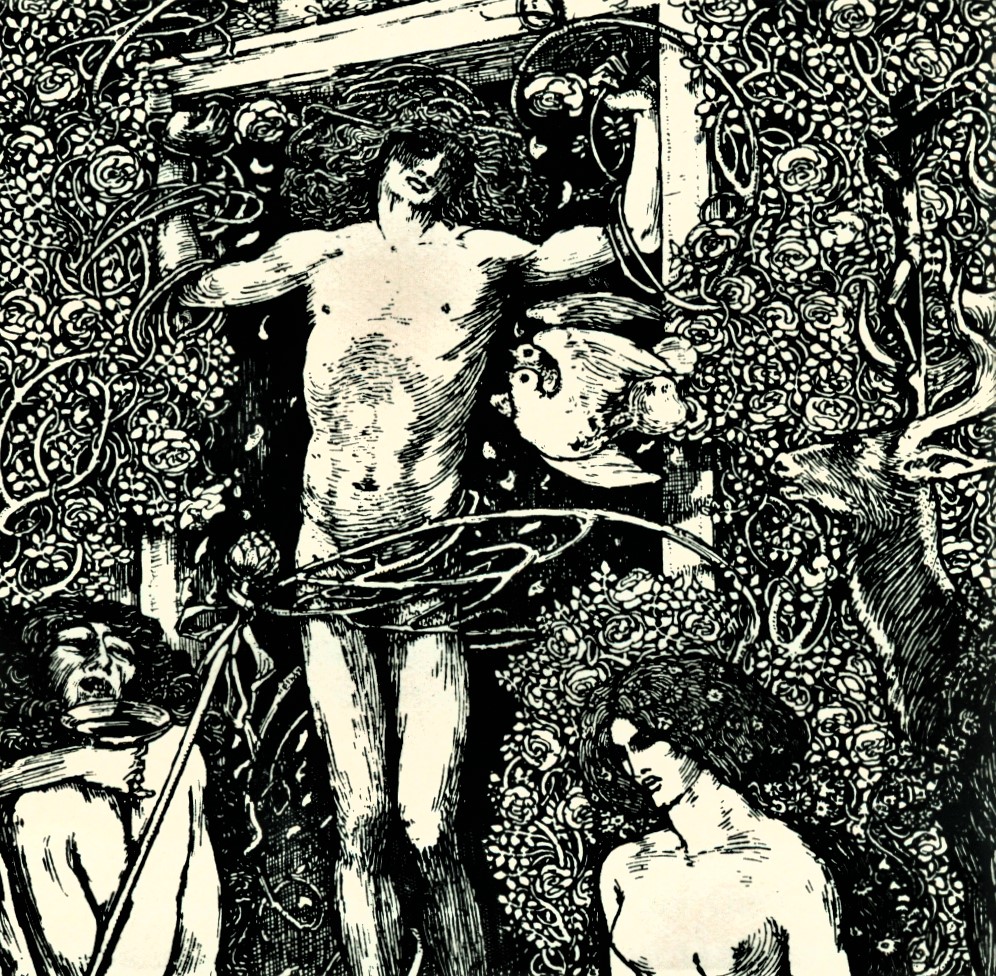

Throughout the exhibit, I link to related digital projects, digitized material, and publicly available resources whenever possible for readers who are interested in exploring a topic further. I also include illustrations from The Yellow Book interspersed with contextual material to visually represent the importance of appearance and aesthetics within the periodical and to demonstrate the literary context in which “Prince Alberic” was published. I have divided this exhibit into sections that cover the context of The Yellow Book and Vernon Lee, three sections containing my analysis of “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady,” and an About page containing information about this project and a works cited list.

Explore this exhibit by clicking the section titles on the banner at the top of this page. You can also click on the images in the exhibit to view their metadata. This project's works cited list can be found here.

Click the browse button below to view all items and metadata in this exhibit.