“His figure was at once manly and delicate”: Representations of Body and Gender in “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”

Just as illustrations and literary contributions in The Yellow Book distort conventional ideas about bodies, morality, and artifice, so too does “Prince Alberic” challenge Victorian attitudes towards queerness by representing bodies that do not conform to social expectations. The representations of Alberic, the Duke, and the Snake Lady include details about their bodies and appearances that reveal hypocrisy and hidden desire. These representations destabilize conventional ideas about what bodies should look like and what types of bodies can be attractive to show that queer desire exists beyond prescribed standards of beauty.

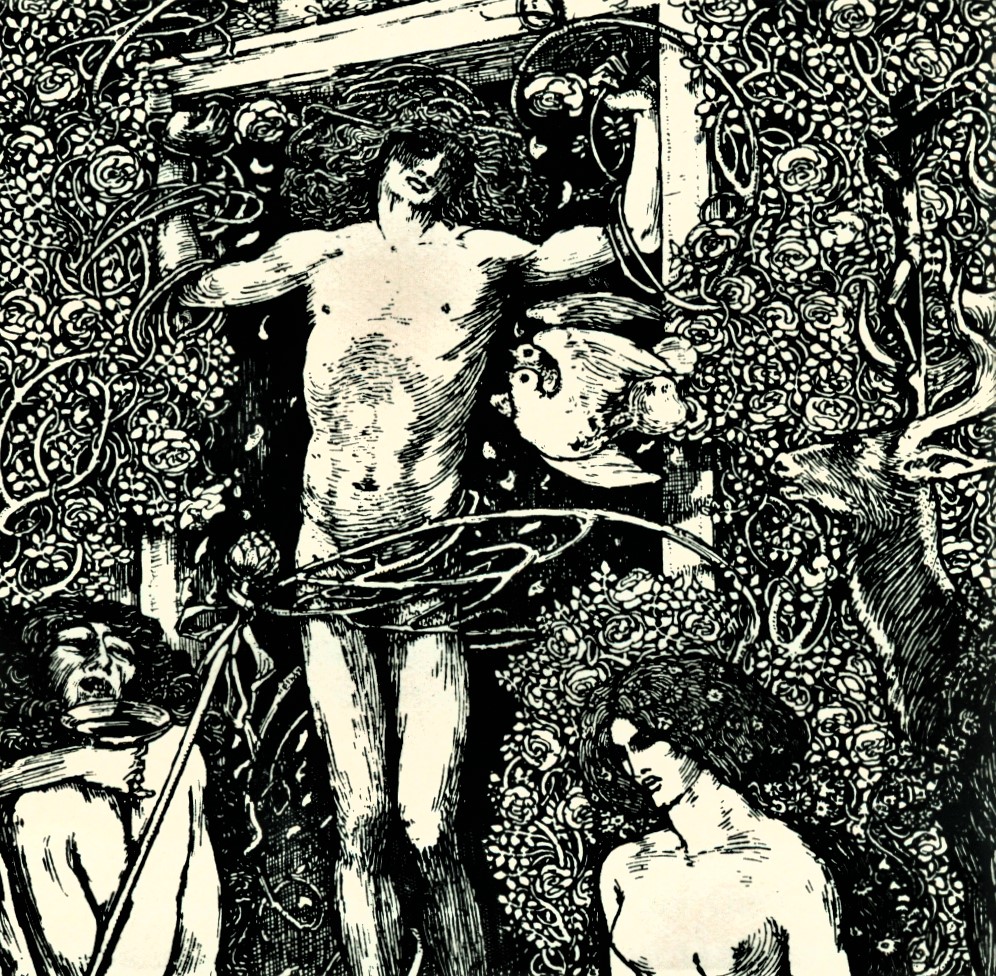

For instance, Alberic occupies a highly prized role within the Duchy of Luna, yet he neither fits neatly into conventions of this role nor into the expectations of his gender presentation. Lee portrays Prince Alberic’s appearance as effeminate, and this portrayal complements Alberic’s disinterest in marriage to distance him from traditional masculinity and the social roles that come with it. Alberic’s interests in “unmanly handicrafts” (Lee 338) also support his portrayal as effeminate. Lee describes Alberic’s appearance in the following quotation: “his figure was at once manly and delicate, and full of grace and vigour of movement. His long hair, the colour of floss silk, fell in wavy curls, which seemed to imply almost a woman’s care and coquetry” (307). This description suggests that Alberic cares about his appearance and beauty and grooms himself in a way that distances his gender presentation from traditional masculinity.

The Duke’s pride in his appearance extends to an all-encompassing obsession. The narrator writes that “when his son had died with mysterious suddenness, Duke Balthasar Maria’s grief had been tempered by the consolatory fact that he was now the youngest man at his own court” (304). However, unlike Alberic, the Duke conforms more closely to traditional ideas of masculinity. Yet Lee draws on characteristics of decadence—specifically, artifice—to suggest that the Duke’s “magnificent” (298) beauty is a performance. The Duke is known as the “Ever Young Prince” (297) by his subjects at the Red Palace. He even has a statue of himself in the Palace, demonstrating his desire for everlasting beauty and youth. The Duke values these traits beyond all else, knowing that they epitomise currency and power.

However, Alberic’s observations about the Duke’s appearance challenge this popular conception of him. Alberic detects a bald spot on the Duke’s head: “beneath the great curly Peruke there was a round blank thing—a barber’s block!” (298). For Alberic to see a bald spot beneath the Duke’s wig suggests that his seemingly perfect appearance is fractured beneath the surface and that the body that is perceived to be exceptionally beautiful is actually flawed. While most of Luna celebrates the Duke’s appearance, Alberic sees the Duke with “diseased fancy” (297), suggesting that what he finds to be attractive diverges from the norm. Lee’s diction in this quotation evokes a sense of decadent decay, as if Alberic’s perspective erodes false appearances through an alternative lens. Alberic recalls a memory from childhood where the Duke, in special dress, looks “as if he had been made of various precious metals, like the celebrated effigy he had erected of himself in the great burial chapel” (297).

By contrast, Alberic is fascinated with difference and novelty—especially to do with the body—and he satisfies this fascination with the tapestry. He initially finds the tapestry interesting because it shows him creatures and plants absent from the desolate Palace, a place of sterility and sameness. The Palace has “no live creatures, except snails and toads, which the gardeners killed” (291). As he ages, Alberic notices the knight and lady at the center of the tapestry and “got to love the lady most” (293). He seems to identify something in the Snake Lady that is “unlike those of the ladies” he sees at the Palace (293). The Snake Lady appeals to some part of Alberic that is missing at the Red Palace, and this interest increases as Alberic continues to uncover parts of the tapestry.

Oriana literally has a different anatomy than humans, and Alberic finds her serpent tail the most beautiful feature of all. While he initially admires her for her golden hair and beautiful clothing, Alberic becomes curious about her lower half, which is obscured by a crucifix. When Alberic sees the full tapestry, he is transformed and “riveted to the ground” in captivation (294). This reaction suggests that Alberic is having an intense internal response to Oriana’s body. Oriana is only half human in the tapestry: “she ended off in a big snake’s tail, with scales of still most vivid” (294). Yet Alberic is enamoured with her difference, loving her “only the more because she ended off in the long twisting body of the snake” (294-95). In this way, the story celebrates difference in the body by depicting Alberic’s desire and intense interest in the Snake Lady.

Alberic’s love for Oriana starkly contrasts his indifference to conventionally beautiful women. After seeing her full form, “scarcely a day had passed without coming to the boy’s mind his nurse’s words about his ancestor Alberic and the Snake Lady Oriana” (312). When the Duke brings him “a celebrated Venetian beauty” to dance for him, Alberic finds that his “grass snake made the same movements as the lady, infinitely better and more modestly” (337). Thus, Alberic’s interest in Oriana illustrates his queer desire that is at odds with social expectations dictating to whom he should be attracted.

Ruth Vanita’s conception of animals as “stand-ins for the love object” (216) informs my interpretation of Oriana as queer coded in this story. Vanita imagines that the animal figure “express[es] the irreducible value of the radically other” (216). Oriana transforms among snake, hybrid human/snake, and full human, her body imbued with symbolism of the Fall via her serpent form. Because her body is non-human, she represents the radical other and Alberic is forbidden to desire her. Dustin Friedman reads the Snake Lady as “a figure not just for lesbianism but for any form of desire that departs from cultural norms, including those forms of queerness that have yet even to be imagined” (Before Queer Theory 142). I agree with Friedman’s reading of the Snake Lady because she resists any type of categorization and stable definition. We see diverse representations of her in the tapestry as an artistic object, a garden snake, an old lady (Alberic’s godmother), and finally as a woman.

“Prince Alberic” also suggests that there are dire consequences for those who defy gendered expectations of the body. While beautiful, Oriana is also described as dangerously magical. Though Alberic adores Oriana’s bodily differences, the rest of Luna finds serpents revolting. After she is murdered, Oriana is found in human form in the prison cell in place of the snake’s body, described in the following quotation: “the body of a woman, naked, and miserably disfigured with blows and sabre cuts” (343). Liggins notes the body seems almost “as if after sexual assault” (48), suggesting that this death is a direct condemnation of Alberic’s queer desire. Her death represents an attempt to eliminate the object of Alberic’s desire.

“Prince Alberic” ends with a sense of inconclusiveness and irresolution: rather than completing Oriana’s transformation into a full human or even saving the Duchy of Luna through marriage, Alberic, Oriana, and the Duke die within weeks of each other and the Palace is left deserted. The story concludes on a note of despair, echoing the feelings of hopelessness and anguish felt by those sympathetic to Wilde in the wake of his trial and incarceration. Yet, the gloom of this ending reproduces the ethos of The Yellow Book and the decadent movement in which Lee writes by depicting the decayed and and “extremely damaged” remnants of the tapestry (Lee 344). Rather than taking this ending literally as the complete destruction of Alberic’s queer desire, I interpret the ending as demonstrating the futility of attempting to eradicate queerness. The tapestry, though damaged, continues to exist and represent the story of the Snake Lady despite continual efforts to destroy or remove it.