“Duty as Prince”: Ancestry, Marriage, and Normativity in “Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady”

“Prince Alberic and the Snake Lady” is acutely aware of the roles that ancestry, duty, and tradition play in upholding heteronormativity to demonstrate the pressures to conform to a certain type of gender and sexuality. The story’s plot shows how the Duke attempts to coerce Alberic into marrying a suitable princess and thereby sustain familial power and wealth. “Prince Alberic” emphasizes the role of tradition within the lives of its characters partly through Alberic’s lineage (he is the third Alberic in his royal ancestry) and partly through marriage as the driving force of the plot.

At the Castle of Sparkling Waters, Alberic is wooed by the Duke’s counsellors (the Jesuit, Dwarf, and Jester) who bring him gifts such as horses, luxurious clothing, and books in hopes of securing a position in the court when he becomes the Duke (Lee 306). These acts of gift-giving position Alberic’s rank as his most important quality. Moreover, Alberic’s indifference to marriage is tolerated by the Duke until the Palace’s bankruptcy leaves him desperate to marry off Alberic to the daughter of “a sovereign of incalculable wealth” (335). There is an economic imperative for Alberic to marry into wealth and maintain the Palace’s power: “there remained to the bankrupt Duke Balthasar Maria only one hope in the world—the marriage of his grandson” (335). This quotation reveals both the Duke’s motive behind finding Alberic a suitable partnership and Lee’s critique of marriage and its conventions in the nineteenth century, especially the effect of marriage on the lives of queer people.

Lee portrays marriage as an economic exchange for Alberic despite a “clear trend to companionate marriages” by the late eighteenth century (Stone 328). While love increasingly became “the basis of marriage” (Stone 326), Lee’s critique suggests that heteronormative expectations of marriage still excluded those with non-normative sexualities from having fulfilling partnerships. The story’s setting in the past (the late seventeenth century) distances Lee from her current moment, allowing for an indirect critique of how marriage upholds generational power and wealth. She constructs this critique by portraying Alberic’s prospective marriage as hyper transactional. Alberic is “displayed” (330) to the court, this verb implying that he is an object of value rather than a person with his own desires and wishes. Alberic, however, resists the social pressures to marry: “he had positively no conception of sacrificing to the Graces” (332). This allusion to Greek mythology suggests that Alberic is unwilling to compromise his own desires to appease the wishes of the Duke and the rest of Luna.

Though Alberic is fascinated with difference and novelty, the setting of the story depicts oppressive sameness and homogeneity that stifles his desires and individuality. Alberic escapes through his transformative experiences with the tapestry. Whereas Alberic finds the tapestry vibrant, alive, dynamic, and “delightful” (296), he experiences the Red Palace as “uncanny” (296), realizing after the removal of the tapestry that “he had always hated both his Grandfather and the Red Palace” (295). The Palace represents uniformity and convention, perhaps the reason why Alberic dislikes his home. The narrator shares that there is a ubiquitous opinion of the palace’s magnificence; however, this remark seems in contrast with Alberic’s feelings about it:

The whole world, indeed, were agreed that Duke Balthasar was the most magnanimous and fascinating of monarchs; and that the Red Palace of Luna was the most magnificent and delectable of residences. But the knowledge of this universal opinion, and the consequent sense of his own extreme unworthiness, merely exasperated Alberic’s detestation, which, as it grew, came to identify the Duke and the Palace as the personification and visible manifestation of each other. (295)

This passage illustrates the gap between Alberic’s sense of self and the person he is expected to become. The narrator’s description of the palace as universally adored contradicts Alberic’s perspective, revealing an incongruity between Alberic’s subjectivity and that of what the narrator identifies as everyone else. This conflict emphasizes the sense of Alberic’s isolation because dislikes what everyone around him adores, signalling Alberic’s difference from those around him. Moreover, the awareness of his varying opinion only magnifies his feelings of unworthiness and disbelonging, almost as if he is foreign to his place of nativity. This difference becomes more profound when we consider that Alberic, as Prince, is in line to inherit the Palace and take his grandfather’s role. If Alberic considers the Palace a personification of the Duke, we can read his dislike of the Palace as a rejection of the expectations and roles placed onto him. Alberic’s unease and sense that he does not belong reveal his awareness of the internal difference between himself and the rest of his community.

The story frames marriage as a necessary responsibility of life, and when Alberic refuses, he is deemed “undutiful” (341). The people of Luna also perpetuate how romance is transactional. For instance, when the Duke “pinch[es] the cheek of a lady of the very highest quality,” it is the lady’s husband and father that are “instantly congratulated by all the court on this honour” (330). This interaction suggests that this woman belongs to the patriarchs of her family and that her beauty and perceived value bring the men status and wealth. Similarly, Alberic demonstrates high levels of intellect, kindness, and strength; however, these traits only matter to the Duke if he can leverage them to find Alberic a wife.

At multiple points, characters reference the importance of lineage in the royal family and the imperative of marrying a “suitable” princess to continue the family line. The narrator reveals that Balthasar, for instance, was “determined to give [Alberic] … a princess worthy to be his wife, and somewhat earlier, for a less illustrious but more agreeable lady to fashion his manners” (290). Here, Balthasar reveals that he expects Alberic to form associations with women suitable for marriage as part of his responsibilities to the Red Palace. In the context of a royal family, marriage indeed carries on the lineage and passes down power and wealth from one generation to the next through reproduction and a blood line. If Alberic doesn’t marry—or if he chooses someone “unsuitable”—this power is at risk. The organization of the palace thus perpetuates a heteronormative system of (unequal) wealth redistribution maintained by lineage and reinforced through institutions such as religion and art. To Lee’s contemporaries reading The Yellow Book, Alberic’s resistance to marriage might read as a suggestion to how queer identity challenged rigid attitudes toward institutions such as marriage.

These concerns about marital duty reflect a larger sense of the contemporary attitudes around sexuality in late nineteenth-century England. Though Lee’s tale may be fictional, it defies attitudes around marriage at the fin de siècle by portraying Alberic’s refusal to conform to socially acceptable desire. The figure of the priest demonstrates the role of religion in perpetuating this system of marital duty. The priest arrives at Sparkling Waters after Alberic has fallen ill and believes that Alberic has been possessed by demons that are causing him to ask questions about serpents and the story of the Snake Lady.

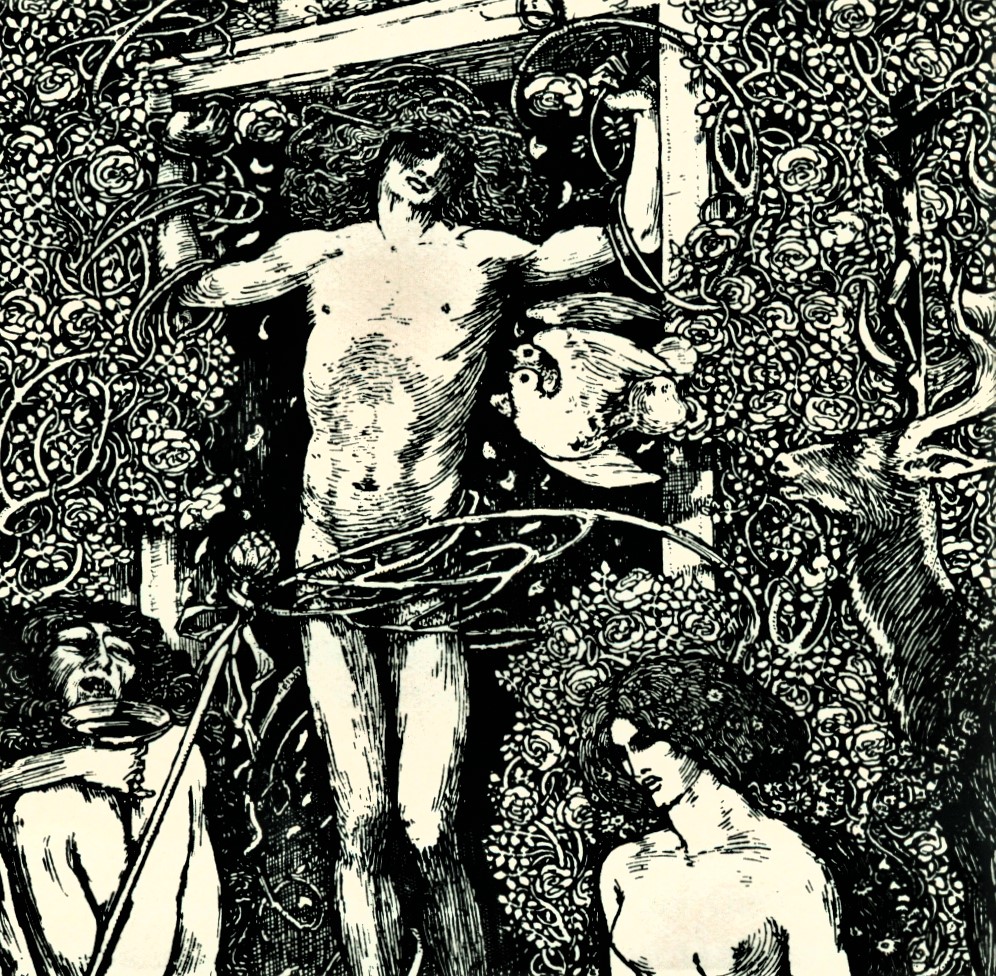

The priest is obsessed with morality and sin, chastising Alberic for even asking about the story. He cries that the story of the Snake Lady is “not a very moral [story] to [his] thinking!” (323). Though the priest does not explicitly say what is immoral about the story, he laments Marquis Alberic’s “left-handed marriage” (324) with the Snake Lady and stresses that Oriana “had been turned into a snake for her sins” (323). This morality defense suggests that even thinking about a story deemed immoral is sinful. The priest’s remark reveals further similarities between the Snake Lady and the biblical story of Adam and Eve in which a serpent tempts Eve into sin by eating from the tree of knowledge. The story of Adam and Eve also details the making of woman and the institution of marriage. Lee using the serpent as the figure that Alberic loves and cherishes references Genesis and underscores the influence of religion as a social force driving Alberic to choose marriage and carry on his lineage while being told to avoid sin.

The priest shares that both of Alberic’s ancestors eventually “fulfilled [their] duty as prince, and married” (Lee 324). Rather than reproducing these attitudes within “Prince Alberic,” Lee subverts these attitudes through parody and critique. Lee parodies the priest’s thinly veiled belief in demons in his exchange with bed-ridden Alberic in the following passage:

Yes, my Lord—there is such—let me see, how does the story go?—ah yes—this demon, I mean this Snake Lady, was a—what they call a fairy—or witch, malefica or stryx is, I believe, the proper Latin expression—who had been turned into a snake for her sins—good woman, woman, is it possible you cannot be a little quicker in bringing those plates for his Highness’s supper? The Snake Lady—let me see—was to cease altogether being a snake if a cavalier remained faithful to her for ten years; and at any rate turned into a woman every time a cavalier was found who had the courage to give her a kiss as if she were not a snake—a disagreeable thing, besides being a mortal sin. (Lee 323)

In this passage, the priest is distracted and rambling without thinking that this tale represents any truth. The repetition of em dashes fragmenting his thoughts show that he is patronizing Alberic while simultaneously condemning the actions of his ancestors. He cannot contain his own judgments from his telling of the story: he emphasizes that Oriana is not a fairy but a witch, which has markedly more sinister connotations, suggesting that this form of magic is connected to immorality and sin. He interrupts his own story to ask a servant to hurry with the food, again suggesting his indifference to Alberic’s curiosity. The priest “pretend[s] to humour the demon who was asking questions through the poor Prince’s mouth,” again demonstrating his underlying belief that this is a fable about temptation (323). Furthermore, the priest prays to saint Paschal Baylon to rid Alberic of demons. He invokes Baylon’s name while telling the story of the Snake Lady to Alberic until he believes that the demon has left after Alberic shouts Oriana’s name, exclaiming “who would have guessed that St. Paschal Babylon performed his miracles as quick as that!” (326). Ironically, the priest believes that the demon is exorcized because Alberic has shouted Oriana’s name when actually Alberic so deeply empathizes with her plight that he cannot help but vocalize his charged emotions.

Despite the social and institutional pressures signalling that Alberic should marry a princess, Alberic’s queerness means that he “had absolutely no eyes, let alone a heart, for the fair sex” (332). Pressures for Alberic to marry continue: he is “presented to several of the most promising heiresses in Italy” in their infancy, and others discuss his impending marriage “behind his back” (333). Alberic’s future marriage becomes an urgent economic prospect after the Duchy of Luna fails to bring in enough revenue, demonstrating the utility of marriage as a transaction of power and wealth amalgamation. The narrator remarks that “there remained to the bankrupt Duke Balthasar Maria only one hope in the world—the marriage of his grandson” (335). These concerns about the future of the Palace, though pressing, demonstrate the lack of care for Alberic’s own desires. Though the Duke offers him the choice of any suitable princess, Alberic’s true desires are ignored, ultimately demonstrating Lee’s point that conventional marriage does not accommodate those with non-normative sexualities.

Moreover, the story resists the conventional ending of many Victorian novels that end in marriage, typified by novels like Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (1847). Though “Prince Alberic” is not a realist novel, its marriage plot certainly plays with the conventions of this genre. While conventional marriage plots end with one or more marriages by the end of the story, “Prince Alberic” defies this expectation. Formally, the story follows the conventions of a fairy tale: the presence of magic, elements of oral storytelling, and characters of high class (royalty). Yet, fairy tales generally end with a “happily ever after,” and this is where Lee diverges from convention. Instead, the story ends with Oriana slashed dead on the ground and Alberic passing away shortly after her. Perhaps this violence suggests a sort of punishment for Alberic’s desires, yet the tapestry prevails: though the palace becomes deserted, parts of the tapestry become upholstery for chairs and material for curtains in the palace, suggesting that the story lives on despite the crumbling of the palace itself. The remains of the tapestry indicate that this cycle will continue after Alberic, just as it repeated for his ancestors. This gruesome, violent ending is the opposite of the neat closure that a wedding brings. It suggests discontent with the status quo that systems of marriage and familial duty neglect the needs of those who cannot conform to heteronormativity.