Needlework

Samplers are pieces of embroidery that test or display the creator’s needlework skills. To learn more about embroidery samplers and how to make them check out this tutorial from Crafting Communities.

Dora De Blaquiere's “Samplers, Past And Present” from The Girl's Own Paper frames the conversation of samplers with an anecdote about sewing in the ancient past. In this case, the paragraph at the top of the third column abruptly veers away from embroidery to discuss the use of linen and thread in Egypt 2,000 to 3,000 years ago. The article continues to examine early samplers, including a sampler by a young girl named Sarah Caporn from 1779 (as shown on p. 589 of the article above). Connecting the practices of girls to Egyptian housekeepers highlights the somatic quality of needlework.

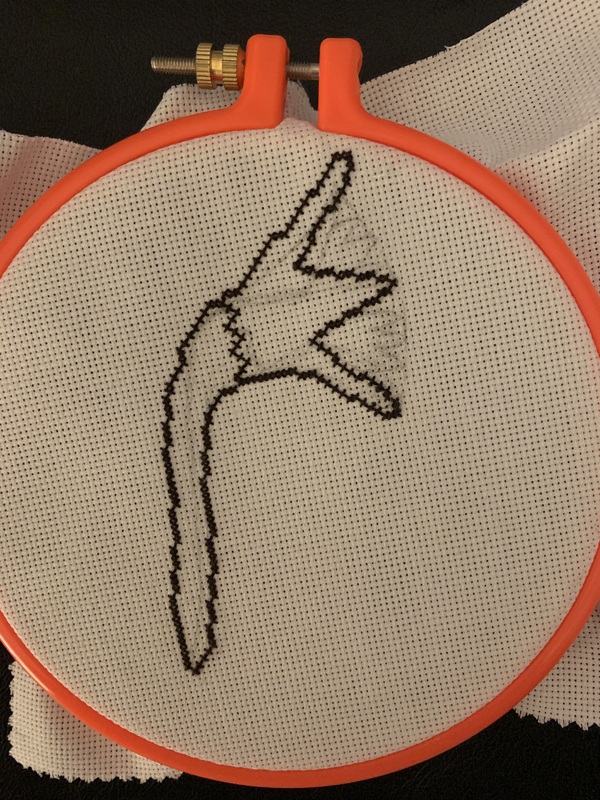

In her article “Wilful Design: The Sampler in Nineteenth-Century Britain,” Chloe Flower writes, “the physical recursiveness of sampler sewing is closely connected to experiences of corporeal pain: hunched shoulders, aching backs, eyestrain, and pierced fingers” (309). My Lotus Sampler is a simple crosstitch on a small square of Aida cloth, and I still managed to feel the pain of a repeatedly pierced finger that Flowers describes. Samplers thus not only display needlework prowess and aesthetic interests but also connect women through physical sensations. Girl readers can understand ancient Egyptians through both the techniques used by these housekeepers (that is, “seaming, over-sewing, stitching, gathering and hemming” [Blaquiere 588]) and the pain inflicted by this work. Embalmers preparing mummies with women's worn household linen solidifies the connection between needlework and the body.

“there are some few universal patterns, but besides these every age and nation has had its favourite design springing from the religion or patriotism of the people. Thus the lotus and beetle have come to be identified with Egypt” - Frances M. Robinson, Atalanta, p.44

In “Embroidery and Lace” from Atalanta (above), The allusion to the preferred symbols of Egyptians contributes to a larger narrative about the historical significance of needlework. Indeed, Frances Mabel Robinson this piece with a bold statement about humanity's innate use of needle and thread: “the use of the needle is one of those fundamental arts so natural to mankind that they may be termed instinctive (...) (43). I cannot say that my experience creating the Lotus Sampler demonstrated such an intrinsic skill. However, Robinson's advice to adopt the colours of designs from Museums did inform my approach.

The descriptions below the images of embroidery and lace provide readers with the necessary colours and techniques to incorporate designs held by the Royal School of Art Needlework and the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum) into their own work. For example, the description for a bird patterned chairback describes the colours and stitches that readers could use: “silk embroidery on linen, foliage in shades of green, and birds in darker bronze. Chiefly carried out in stem stitch” (Roninson 48). Without being explicitly instructional, Atalanta brings the long history of needlework into conversation with the contemporary activities of girls, educating readers about not only their domestic responsibilities but also ancient cultures and the historical significance of womanly occupations like needlework.

Art Needlework refers to a type of free-style embroidery (embroidery using a variety of stitches) that gained popularity in late nineteenth century Britain under the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement (click here to learn more about textiles in the Arts and Crafts Movement).

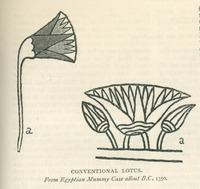

Although written for a lower class of reader than Atalanta, Helen Marion Burnside's "Art Needlework" series in The Girl's Own Paper (above) similarly encourages readers to visit the museum to find patterns for their embroidery. Fortunately, even if the readers of The Girl's Own Paper did not have the means to visit the museum they could still find plenty of inspiration from ancient sources in the pages of their periodical. For example, "Flowers in History" (below) includes an illustration of a conventional lotus from an "Egyptian Mummy Case about B.C. 1350."

This lotus design can be found on the coffin of the Mummy of Hor, which would have been in the British Museum's possession since 1823.

So, taking Burnside and Robinson's advice, I turned the "Conventional Lotus" design (above) into a cross-stitch sampler. I used the outline from The Girls Own Paper and the colours from images of the mummy coffin as a guide. The Lotus Sampler connects the mummy and the sampler in the style of Blaquiere's article, placing women’s work—and, by extension, the samplers made by girl readers—directly into the coffins that girls could see on display at the British Museum throughout the Victorian era.