Fan Painting

The articles on fan painting in Atalanta and The Girl's Own Paper capitalize on Victorian girls interest in fans. Fans were a Victorian girls’ introduction to the coded language of courtship. As evident in the poem “A Japanese Fan” by Margaret Veley (which you can read on Digital Victorian Periodical Poetry), the language of the fan allowed women to express their agency in courtship without appearing inappropriately forward in choosing a partner:

Lying here—bamboo and paper,

from Japan.

It is nothing—very common—

Be it so;

Do you wonder why I prize it—

care to know?

Shall I teach you all the meaning,

the romance

Of the picture you are scorning

With a glance? (Veley 380)

Veley’s poem also demonstrates Victorian girls’ awareness of the materiality of fans as well as their inherent exoticism (in this case, as a product from Japan).

“perhaps no invention of luxury and adornment has played a more prominent part in the world’s history than the dainty trifle which forms the subject of this sketch” - E. Taunton Williams, Atalanta, vol. 10, p. 302

Alongside images of lavish painted fans, E. Taunton Williams article in Atalanta vol. 10 outlines the long and historically entrenched history of fans. The obvious sources of the Victorians interest in fans are East Asian—mainly, fans from or inspired by Japan (as in the poem above) and China. In the mid-nineteenth century, England became increasingly interested in the “Eastern world” as a whole (generally, the “Eastern world” refered to countries east of the Mediterranean [Orient, n]). For example, furniture, ceramics, textiles, and paintings inspired by Japanese designs grew in popularity (click here to learn more). Williams’s acknowledges the prominence of China and Japan in fan painting traditions by referring to them as, “the foster parents of the fan” (303).

Even in the context of fans, a subject ripe for focus on East Asia, ancient Egypt appears: “among the people of ancient Egypt the pedum, or flabellum, was the emblem of happiness and heavenly repose, and was the chief ornament of cars and palanquins in triumphal marches and celebrations” (Williams 303). By associating the fan—a “dainty trifle”— with powerful symbols of ancient Egypt, Williams creates a juxtaposition between the familiar or even trivial items of girlhood with the exotic spectacles of an ancient civilization. As David Gange notes in his book Dialogues with the Dead, “familiarity was consistently as much a part of Egypt’s image as exoticism and orientalised spectacle” (Gange 51).

In his book Orientalism (1878) Edward Said uses the term “orientalism” to refer to the ideological process by which myths and false images about the “Eastern world” were constructed by “Western” discourses, including popular culture, literature, and art. On orientalism, Ross Murfin and Supryia M. Ray observe, “this stereotyping facilitated the colonization of vast areas of the globe by Europeans” (307). Egyptomania in nineteenth-century girls' print culture does not align with malicious representations of the “Eastern world.” The associations between ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome work to make ancient Egypt biblical, classical, and awe-inspiring. However, such representations of Egyptian culture still produced the same kind of imperial ideologies that facilitated colonialism, neutralizing any threats by making Egypt familiar, understandable, and decorative.

To create my fan, I followed a tutorial from The Girl’s Own Paper vol. 3 by an unknown author. Like Williams’s article in Atalanta, this guide to fan painting traces girls’ interest in fans to the ancient and prestigious fans on tombs in Egypt: “on the tombs at Thebes representations of this useful article are found, by which we learn that they were known three thousand years ago” (659).

As the author notes, fans can be made of vellum, silk, gauze, or paper; although, they recommend that the readers of The Girl’s Own Paper use gauze to achieve the flat and easily paintable surface of a hand screen fan rather than the creased surface of a folding fan. I ignored this advice in favor of painting on a premade paper fan. Following the author's advice that the colours on painted fans should be “most delicate,” I chose to work with watercolours (660). Fan paintings actually ranged from delicate to ornate. For example, the mid-nineteenth century painted fan on the right (which features two obelisks in the far right panel) includes bold colours and gold detailing to evoke the exoticism of the Turkish scenes on the panels.

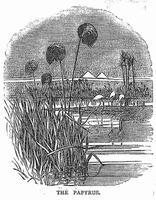

The author of "Fans, and How to Decorate Them" copies two figures from a painting by H. Juston titled, “the Noon-Day Walk,” to avoid "fear of bad drawing, and yet have a fan that is in so far original that no one else has one just like it" (660). For the design on my fan, I replicated an engraved illustration from The Girl’s Own Paper vol. 1 titled “the papyrus” (left). This illustration not only compliments my fan medium (paper) by heading an article about the history of bookbinding but also depicts an exotic Egyptian vista. Egyptian motifs such as pyramids, sphinxes, obelisks, lotus flowers, animal-headed gods, scarabs, and cats recur throughout nineteenth-century girls print culture. In her article “Reconstructing Ancient Worlds” Stephanie Moser argues, “this reductive quality renders the iconography highly adaptable for use” (1297). I aimed to similarly capture “this reductive quality” of Egyptian iconography in the ninteenth century by choosing an image that communicates ancient Egypt through prominent pyramids. The adaptability of Egyptian iconography allowed Victorian girls’ to easily express their interest in ancient cultures through crafting—a traditionally domestic activity for girls that at first seems at odds with the popular image of Victorian Egypt as a site of exotic and dangerous adventures. However, the frequent use of these motifs also removes Egypt from its contemporary context. Much like orientalism is an ideological process that produces false images about the “Eastern world” to facilitate colonization, Egyptomania produces a feeling of awe towards Egypt that fixes this country in the ancient past.