Return to "Home" Continue to "Conclusion -- The Meaning of Citizenship"

Becoming an American Citizen

Acquiring citizenship in the United States has never been an easy process for any immigrant, and for Fred Preuss it was no different, as the collection of letters in the gallery below testify to. Preuss wrote these letters to many different people he was acquainted with, asking them to vouch for his residence in various areas of the United States, which was necessary for his citizenship application. This was all part of the citizenship process in the United States, which he couldn’t even apply for until he had lived there for five years. Please click any of the letters below to enlarge it.

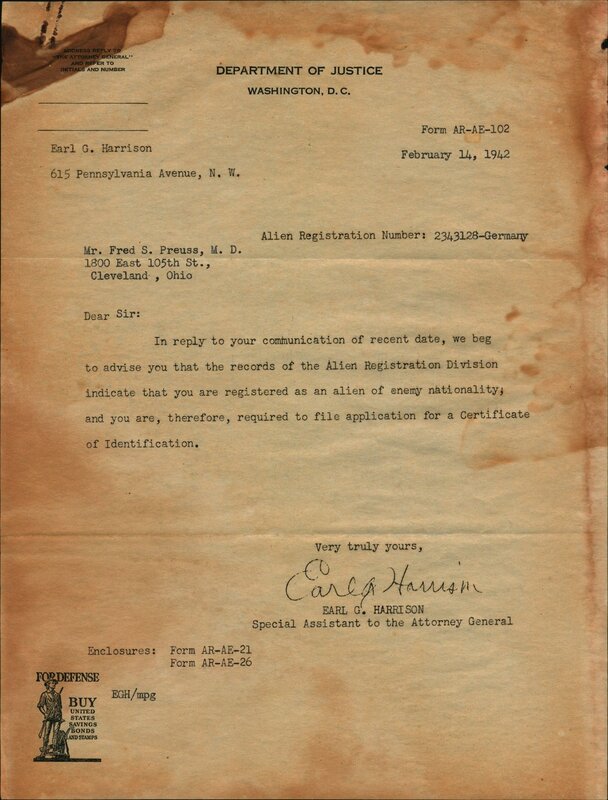

Perhaps the most ironic aspect of Preuss’s path to acquiring American citizenship is the fact that he was registered as an “enemy alien” because he was from Germany, even though Germany itself had taken away his right to full citizenship (J. Preuss 54). As Anne Schenderlein writes, “[w]hereas the Nazis had robbed them [German Jewish immigrants] of their status as (full) German citizens, the American enemy alien classification reduced them to their German origins, completely disregarding their Jewish backgrounds and persecution by the Nazis” (110). Moreover, in 1941, the Nazi regime expatriated any German Jews living outside the Reich “for general residential purposes,” which likely could have included Preuss (Salwin 375). As Lawyer Robert Kempner explained in 1942, thousands of German immigrants who were considered enemy aliens residing in the United States were “technically not German citizens” (824). Whatever the technical state of the matter was, however, the special assistant to the attorney general still wrote to Preuss in 1942, stating that because Preuss was an enemy alien, he had to register for a Certificate of Identification (see the letter to the right). People termed enemy aliens had to carry these cards or else they could be subject to internment (Krajewska 68 – 69). In addition, some enemy aliens faced occupation, freedom of movement, and travel restrictions (Schenderlein 109).

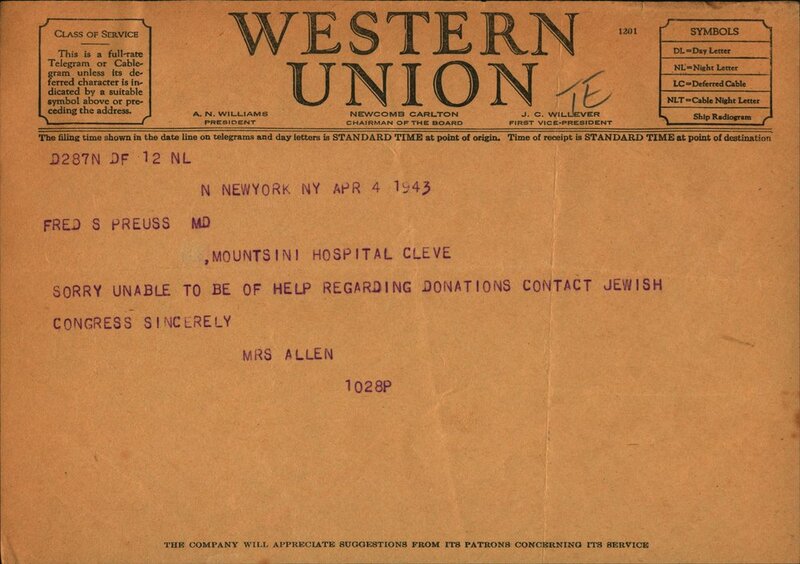

Being able to acquire citizenship was in and of itself a long and somewhat tedious process for all immigrants. As previously mentioned, a person had to reside for five years in the United States before they could even apply for citizenship. Furthermore, as the collection of letters above demonstrate, Preuss needed many witnesses “to vouch for his character and to account for all of his time in the US between 1938 and 1943” (J. Preuss 54). This of course took a long time, and some people even refused to vouch for him. For instance, Preuss wrote a letter to Mrs. Allen asking her to vouch for his residency in New York. As an expression of his appreciation, he offered to donate to the American Jewish Congress, with which she was affiliated. Mrs. Allen, however, denied this request (note her response in the telegram to the right).

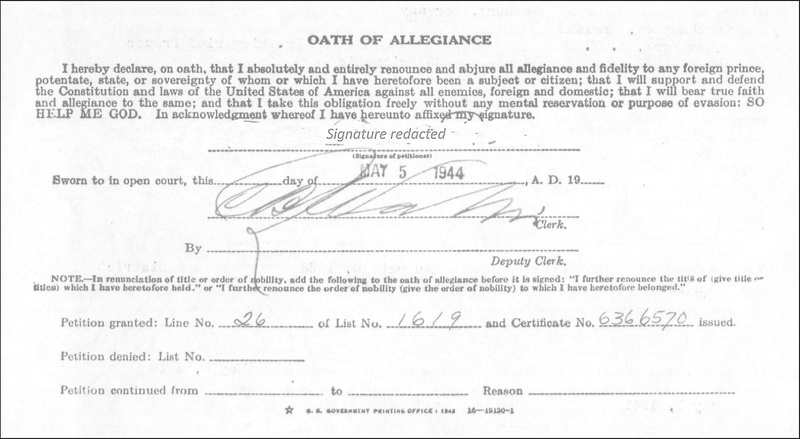

In addition to providing these references, Preuss had to appear before a five-person committee for a citizenship hearing in Washington. He demonstrated his commitment to the United States via a variety of different means, including “his purchase of $1,000 in war bonds, donating blood to the Red Cross, and participating in the Civilian Defense Auxiliary Group and in the Mobile Emergency Team of Mount Sinai Hospital” (J. Preuss 54). Eventually, Preuss’s efforts paid off, and he was finally able to become a citizen, after which one of his first acts was to join the Army Medical Corps, where he served for almost three years until May 1947 (J. Preuss 54). It is difficult to comprehend just how meaningful it must have been for Preuss to finally gain all the rights that should come with the status of citizenship.

Moreover, in addition to the effort it took to acquire citizenship, he also faced many other challenges in the United States, such as being unable to find work for a couple months upon his arrival (J. Preuss 54). However, in spite of these and other challenges, as the life of an immigrant was rarely an easy one, Preuss built a life there and never went back to the nation that had essentially renounced him (K. Preuss 13). He never heard from most of his extended family after the war and presumed they perished in the Holocaust (J. Preuss 54).

Return to "Home" Continue to "Conclusion -- The Meaning of Citizenship"

Works Cited

Allen, Bernadine. Telegram to Fred Preuss. 04 April 1943. Holocaust and World War II Memory Collection. Fred Preuss Collection. University of Victoria Special Collections and Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC, 14 April 2021.

Harrison, Earl. Letter to Fred Preuss. 14 February 1942. Holocaust and World War II Memory Collection. Fred Preuss Collection. University of Victoria Special Collections and Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC, 14 April 2021.

Kempner, Robert. “Who Is Expatriated by Hitler: An Evidence Problem in Administrative Law.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register, vol. 90, no. 7, 1942, pp. 824 – 829. JSTOR, doi: 10.2307/3309251.

Krajewska, Magdalena. Documenting Americans: A Political History of National ID Card Proposals in the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Oath of Allegiance (Preuss, Siegfried), 1944, Fold3 File #139752208, Naturalization Petitions, 1867 –9/26/1991, Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 – 2008, National Archives at Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Preuss, Fred. Letter to Bernadine Allen. 01 April 1943. Holocaust and World War II Memory Collection. Fred Preuss Collection. University of Victoria Special Collections and Archives, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC, 14 April 2021.

Preuss, Karl. Introduction. Remembering, by Fred Preuss, University of Victoria, 2018, pp. 10 – 13.

Preuss, Jennie. Epilogue. Remembering, by Fred Preuss, University of Victoria, 2018, p. 54.

Salwin, Lester. “Uncertain Nationality Status of German Refugees.” Minnesota Law Review, vol. 30, 1946, pp. 372 – 394. The University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217207297.pdf.

Schenderlein, Anne. “German Jewish ‘Enemy Aliens’ in the United States during the Second World War.” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute, no. 60, 2017, pp. 101 – 116. German Historical Institute Washington DC, www.ghi-dc.org/fileadmin/user_upload/GHI_Washington/Publications/Bulletin60/101.pdf.