Isa Milman

Close to 3.3 million Jews were living in Poland before the outbreak of World War II. Of the approximately 350 000 that survived the Holocaust, 230 000 of them survived in the Soviet Union (Jockush and Lewinski). Many of these survivors, like Olek and Sabina Milman, found themselves in Soviet prison camps, or gulags, as a result of forced deportation during the war.

The following is the story of the Milmans and their survival in the Itatka gulag.

These pins demarcate important locations to the Milman’s story. Although there are many more that could be added, for the sake of this exhibit, these are the most noteworthy.

- Victoria, BC, Canada - Where Isa and the documents featured in this exhibit reside today.

- Kostopil, Ukraine – Where Olek & Sabina lived before their deportation. (Pre-World War Two, Kostopol was part of Poland.)

- Stolin, Belarus - Olek's hometown and where he went to school. (Pre-World War Two, Stolin was part of Poland.)

- Itatka, Tomsk Oblast, Soviet Union (now Russian Federation) – This is the approximate location of the Itatka gulag. Olek & Sabina spent nearly 2 and a half years here, between 1940 and 1943.

- Fergana, Uzbekistan – After they were released from the gulag, Olek & Sabina were deported to Fergana, where they stayed for 2 years before being expatriated back to Poland.

Deportation – 1940

Olek and Sabina Milman were living in Kostopol, Poland (now Ukraine) when they were deported in 1940. The day began as normal; Olek left for work at the quarry. However; on this day he was picked up by Soviet officials and taken to the train station. The reason being - his alleged expression of interest to return to Germany. This claim was entirely unfounded. He was able to get word to Sabina, who managed to pack a few documents, some supplies and share a brief goodbye with her family, before joining him at the station.

Sabina was pressed to sign a confession claiming she was a traitor and that, like her husband, she wanted to leave Soviet controlled Poland and return to Germany, but she refused. She only signed a document stating that she chose to accompany her husband. This meant that she was a volunteer, not a prisoner, something that would be a crucial distinction upon arrival in the gulag. Thus began their 26 day journey by cattle car from Kostopol to Itatka, Siberia, the second to last stop of the rail line.

Life in the Gulag – 1940-43

Olek, like many others, was a victim of false arrest at the hands of the Soviets. No charges were ever filed because no crime had been committed. Unfortunately, due to the lack of crime, there were no files or paperwork, or trial, meaning there was no sentence. No sentence meant no end date to their imprisonment, forcing them to work until they were released or died due to exposure or exhaustion. Polish Jews, political prisoners, criminals, and everyday people like Olek and Sabina Milman found themselves trapped in the gulag for an undetermined amount of time.

During what would be almost two and a half years of living in the Siberian tundra, they were subject to primitive living conditions, menial food rations and inadequate clothing for the extreme temperatures of Itatka. The camp consisted of simple wooden buildings without heat or running water. There was a central watchtower patrolled by armed guards and a fence with barbed wire marking the perimeter of the camp; Itatka was a prison camp.

Olek was subject to hard labour, working as a machinist and logger. Because of his knowledge and experience, he was assigned to maintain the tractors. His job was to ensure they were always in good working order, and to use them to remove felled trees.

Sabina’s situation was unique, as she volunteered to go with her husband to the gulag. Sabina was particularly gifted with languages, and because she spoke fluent Russian she was assigned to be the personal translator of the camp commandant. She was also in charge of the officers' dining room and keeping track of related supplies.

Due to these important distinctions between her and the others who had come on her transport, she was awarded certain privileges. For example, she and Olek were able to stay in the guard’s room, a small semi-private room off of the main barracks that housed the other prisoners. This small separation between the Milmans and nearly 200 other people housed in their barracks allowed them some moments of reprieve. With Sabina’s job in the dining hall, she was allowed the same rations as the guards, and would share them with her husband. She was also able to obtain warmer clothing and waterproof boots for Olek during the frigid winter months.

Release from the Gulag- 1943

June 22, 1941, marked an important moment in the Milmans' story. After Operation Barbarossa, when the Nazis declared war on the Soviet Union, Poland became an ally in name only, as Poland had ceased to exist since September 1939. This political shift changed the status of many of the Poles imprisoned in the gulag. This change in status, however, did not translate into an immediate release.

Olek and Sabina, like many other Polish citizens, were essentially still trapped in the gulag until 1943. The Soviet Union was under attack and work had to continue. At this point, Sabina was forced to work outside with Olek, stacking wood and doing other necessary jobs. Even if they were to be freed by their Soviet captors, they had no means, financial or otherwise, to leave; and they had nowhere to go. They wanted to be reunited with their families, but how? Were their families safe? Were they even still alive? How could they get any news of their fate? The logistics of trying to navigate life in an enormous foreign country during wartime in the 1940s was unimaginable.

When they were finally released from the gulag, they were sent to Fergana, Uzbekistan. The distance between Itatka and Fergana is approximately 2900 kilometers, though the journey could have taken weeks depending on the route they took. Trains were constantly being rerouted and prioritized in order to send supplies and manpower to the front lines. The snake of cattle cars relocating former prisoners of the gulag was not a priority. The Milmans spent over two years in Fergana, trying desperately to communicate with family and organize a way home. They were only released by the Soviets for their return to Poland in late spring of 1946, one year after the official end to the war.

Surviving Documents –

Click on each document and photo for more information.

When the Milmans were deported from Kostopol in 1940, Sabina had only minutes to pack for both her and her husband. She didn’t know how long they would be gone. She didn’t even know where exactly they were going. What do you pack when you’re being deported?

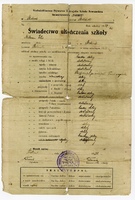

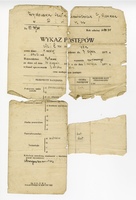

She managed to bring with her some important documents belonging to both Olek and herself. Of these documents, the three pictured above, are the only ones that survived. The graduation certificate, report card and Polish Army identification book all belong to Olek.

Continuation of Memory –

The story of Olek and Sabina Milman did not end with their release by the Soviets in 1946. It also didn’t begin in 1940 with their deportation to the Gulag. Olek and Sabina had accomplished and endured so much more than what this 6-year period describes. Their story is large and complex, and to try to configure it in a way that would be accessible and engaging in a digital exhibit would be a near impossible task.

I remember one of the first meetings Isa and I had over Zoom. I was writing notes as fast as I could while simultaneously learning about the incredible lives her parents led and the sheer distance their journey took them. At the end of the call, I remember Isa pausing and asking me if I thought that there was enough here to create the exhibit. Yes.

The most difficult part was deciding which part of the story we were both comfortable sharing with the community, and if it could be effectively told in an exclusively digital format. While going back and forth about what we wanted to say, Isa mentioned something that stuck with me throughout the project. “What you put in is important, but what you leave out is equally important.”

In this case, we “put in” an important chapter of Olek and Sabina’s life, their deportation to the Itatka Gulag then further displacement to Fergana. What we decided to “leave out,” was their journey back to Poland, stays in various displaced persons camps in Germany and their eventual immigration to the United States to begin a new life with their young family. We left out the stories of Isa and her sisters, how they were impacted by their parents' experience and what they’ve gone through in their own lives.

Our goal with this exhibit is to offer a snapshot of two incredible people and how they were able to survive six years of uncertainty and unanswered questions. The story of the Milmans describes an experience often overlooked when studying the Shoah – that of Jews who survived in the Soviet Union.

Creators of This Page -

Isa Milman is an award-winning writer, artist and poet, based in Victoria, BC. She was born in a displaced persons camp in Germany, before her family was able to be freed from Europe and immigrate to the United States. After graduating from Tufts University in Boston, she moved to Montreal where she received her masters in occupational therapy at McGill and taught there for ten years. She eventually moved to Victoria, where she was the Epilepsy program coordinator for a local non-profit. Throughout her work, she has always had a focus on mental health and rehabilitation. She is an accomplished writer, with three published collections of poetry; Between the Doorposts, Prairie Kaddish, and Something Small to Carry Home; each of which has won the Canadian Jewish Book Award for Poetry. She has had poems, articles and other works published in numerous magazines, journals and newspapers. Her upcoming memoir Afterlight, which tells this family history, will be released in October 2021 through Heritage House Publishing.

For more information about Isa and her work, visit her website - www.isamilman.com

This digital exhibit is the result of the collaboration between Isa and myself, Kayla Aspelund. I graduated from the University of Victoria in 2017 with a degree in History. My focus was on Eastern European and Slavic history during the 20th century, as well as Soviet involvement in the Holocaust. I returned to Uvic in 2019 to pursue a second undergraduate degree. Academically, I have studied the Stalinist-era and I am quite familiar with the Soviet gulag. This is the first time, however, that I have had the opportunity to work one-on-one with survivor testimony. I am extremely grateful to have been able to explore the story of Olek and Sabina with Isa's guidance. Working with Isa to create this exhibit has been an incredible experience, and I cannot thank her enough for sharing this story with me.

Works Cited