Return to "Home" Continue to "About the Contributors"

Conclusion -- The Meaning of Citizenship

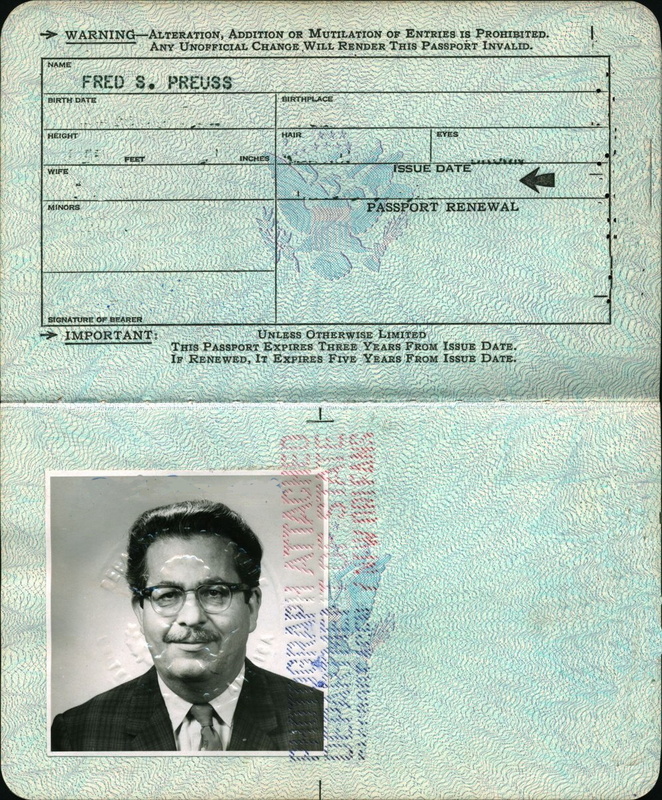

When we consider the possibility of actually losing the rights of full citizenship, as Preuss and others did in Nazi Germany, the latter concept seems very significant, as it no longer remains a given. As Linda Kerber writes, “[t]he status of citizens, which in stable times we tend to assume is permanent and fixed, has become contested, variable, fluid” (833). The rights accrued to citizens has always been and remains a complicated subject, bound together with concerns about race, gender, and other such issues. While we tend to think of citizenship as endowing people with an inalienable set of rights, is this really the case? It certainly was not the case in Nazi Germany when supposedly inalienable rights were incrementally taken away from the Jews and other marginalized groups, rendering citizenship basically valueless in their case. What then is the true meaning of citizenship? Does everyone have equal access to this status? Lindsey Kingston writes:

“In today’s international system, citizenship is limited by the norms of state sovereignty and has been traditionally used to recognize a person as fully human, or worthy of rights protection—yet this robust form of membership is limited or missing entirely for vulnerable populations around the world. In short, viewing citizenship as a natural and inalienable right might seem natural, but it has not been proven as such throughout history.” (6)

In essence, even today, not everyone has access to the protection and rights due to citizens. Moreover, when certain people, particularly those belonging to marginalized groups, are deemed unequal to the rest of society, the definition of citizenship itself becomes very uncertain, unstable, and sometimes altogether meaningless to these groups. Kingston references citizenship’s use as a weapon in Nazi Germany, discussing how this exemplified symptoms of much deeper social issues that emerged in stark detail when associated with such governmental actions (66). The undercurrent of antisemitism within German society, which became increasingly radicalized under the Nazi regime, was then the real issue responsible for what occurred to Preuss and other German Jewish citizens at the time.

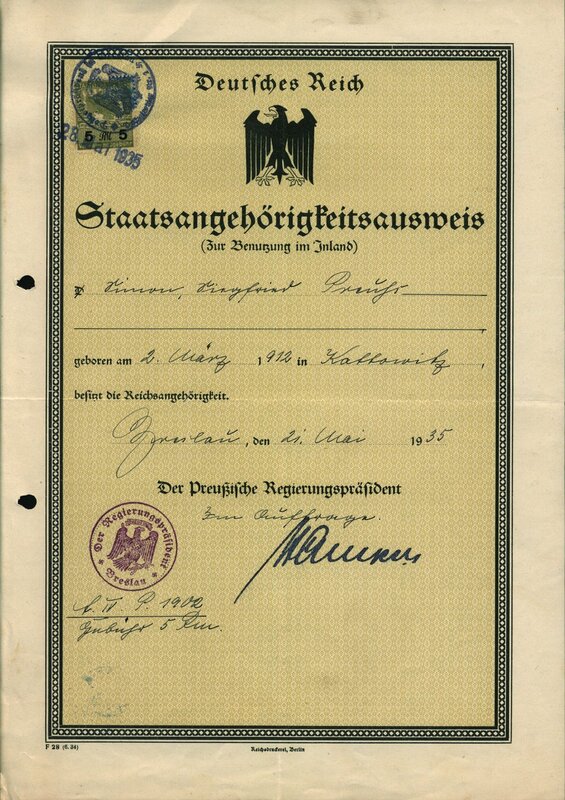

While Preuss and others were not yet “demoted” from their status as full citizens in the early years of the Nazi regime, their rights as citizens began to be taken from them. Classifying them as subjects in 1935 was merely another step in this process of disenfranchisement that had already begun earlier. To the Nazi Party, the meaning of citizenship had changed, and it was now a discriminatory status awarded based on their own definitions of race rather than actual nationality. In the case of Preuss and others, the protection and the freedoms traditionally ascribed to citizenship were no longer a reality.

“Citizenship is man’s basic right for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.” ~Chief Justice Earl Warren

“To this day I believe we are here on earth to live, grow up and do what we can to make this world a better place for all people to enjoy freedom. Differences of race, nationality or religion should not be used to deny any human being citizenship rights or privileges.” ~Rosa Parks

Return to "Home" Continue to "About the Contributors"

Works Cited

Kerber, Linda. “The Meanings of Citizenship.” The Journal of American History, vol. 84, no. 3, 1997, pp. 833 – 854. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2953082.

Kingston, Lindsey. Fully Human: Personhood, Citizenship, and Rights. Oxford University Press, 2019. Oxford Scholarship Online, doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190918262.001.0001.

Parks, Rosa. Quoted in: Ismail, Sabah. “The Black Woman Who Sat Down to Make a Stand.” Medium, 08 October 2020, medium.com/the-pink/the-black-woman-who-sat-down-to-make-a-stand-e8c5038fa61b.

Warren, Earl. Supreme Court of the United States. Clemente Martinez PEREZ, Petitioner, v. Herbert BROWNELL, Jr., Attorney General of the United States of America, 1957. Legal Information Institute, www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/356/44.