Return to "Home" Continue to "Becoming an American Citizen"

The Nuremberg Laws and Other Anti-Jewish Legislation

Early Legal Measures against the Jews

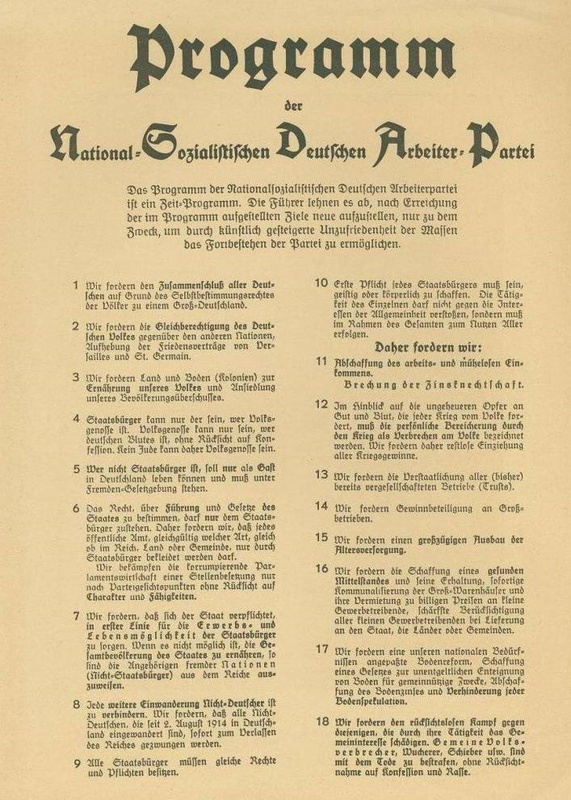

To provide some historical context for Preuss’s experiences, this page will discuss some of the pre-World War II legal measures enacted by the Nazi Party against the Jews. Even as early as 1920, the Nazi Party Program already included anti-Jewish goals. However, Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 resulted in the passage of additional discriminatory legislation and increased persecution of the Jews and other marginalized groups.

Robert Gellately and Nathan Stolzfus explain that the “major questions facing the new dictatorship were where to begin establishing a racially pure ‘community of the people’ and what to do about Hitler’s call for a ‘moral purification of the body politic’” (3). Immediate targets included communists and other political opponents, but arguably there was no immediate and direct attack on the Jews (Gellately and Stolzfus 5 – 6). Alon Confino counters this idea, stating that “[t]he Third Reich began, not with a slow increase of violence against Jews, but with a massive, explosive attack on their civil, political, and legal rights in precisely the everyday places where one feels most secure— buses, workplace, home, one’s own body” (29). The Jews no longer had the protection of the police, and violence against the Jews began to be encouraged (Confino 29 – 30). Thus the Jews, while still legally full citizens of Germany, were losing their right to protection. Various legal measures were enacted against the Jews on a local level, if not yet on a national level (Confino 52).

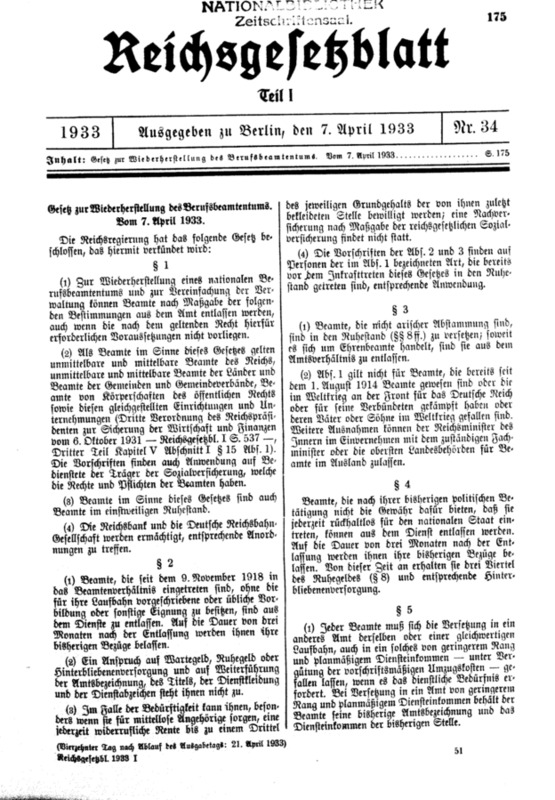

Law for the Restoration of a Professional Civil Service

One of the most overt legal actions against the Jews during these first years was the passage of the Law for the Restoration of a Professional Civil Service, which made it quite a simple task “to purge Jews and others from the civil service” (Gellately and Stolzfus 7). This law was passed in 1933 and essentially legitimatized discrimination against “non-Aryan” employees who were civil servants, allowing businesses to remove them from their positions if they saw fit. It not only targeted Jews, but also targeted other minority groups deemed racially unassimilable by the Nazi regime. This law served “as a precedent for the exclusion of Jews from other jobs. Most ‘non-Aryan’ students were barred from attending German schools and ‘non-Aryans’ were forbidden to take final state exams for many occupations” (“Anti-Jewish Legislation” 1). At this point, it would have been challenging, even if not yet impossible, for medical students like Preuss to get their doctorates even as early as 1933. Other measures and actions perpetrated against the Jews increased in the following years, which particularly focused on purges of the arts and the universities (Confino 38 – 39). Preuss explained:

“As the Nazi influence and power rose, it didn’t take long for every single Jewish professor, or even anyone of Jewish descent, to all lose their position, particularly after the Nuremberg laws had been enacted...they were replaced with politically trustworthy [people]. Of course the quality of teaching naturally suffered considerably because people elevated to higher positions were obviously not fit to do so but because they fitted into the political program.” (49)

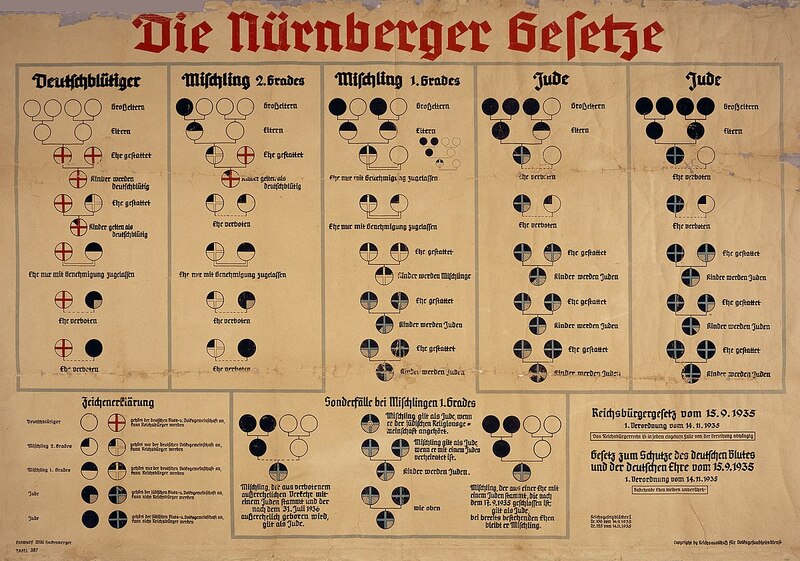

The Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws were enacted in 1935, defining the Jews as a racial group that was distinct from the rest of the “Aryan” population. With these laws and ensuing additions, German Jews were deprived of the rights of full citizenship, and intermarriage between Jews and so-called “Aryans” was forbidden (Meinecke and Zapruder 28). Other marginalized groups, specifically the Roma and Sinti and people of African descent, were not explicitly mentioned at first, but the laws regarding citizenship and intermarriage were extended to cover them a little later (Rosenhaft 163).

While there had certainly been discrimination against the Jews prior to this date, these laws “brought a certain order and regularity to anti-Jewish policies. They codified in law the relations between Aryans and Jews” (Confino 81). German Jewish nationals were now considered subjects, not full citizens, which helped provide the basis for similarly exclusionary supplementary decrees that “progressively separated Jewish Germans from their fellow country people, legally, economically, psychologically, and physically” (Fraser and Caestecker 396). The term “subjects” put German Jews in a very untenable position in society. As Lester Salwin explains, despite the fact that the latter had lost any discernable protections typically due to citizens, “the Nazis retained their hold over the Jews as ‘subjects’” (377). They became what Salwin terms “citizens second-class” (373). In essence, despite the fact that German Jews had none of the rights of full citizens, they still technically “belonged” to the Reich.

More laws followed these that further restricted German Jews from participating in any sectors of society (Confino 61). Increasing numbers of Jewish businesses were taken away from them, and Jews faced growing employment and education restrictions. Jewish university students, like Preuss, were often no longer allowed to take their doctoral exams (Meinecke and Zapruder 27 – 28). Preuss referenced his own experience with the passage of these laws, stating that “on a personal level, I did manage to get through medical school, although in the examinations I took, including the Physikum, the examiners were rude, particularly during the oral examination, making reference to my Jewish appearance and Jewish origin... Still, we could finish school, under a lot of harrassment...” (49). Please watch the video below for more information on these laws.

Legal Measures from 1935 to 1938

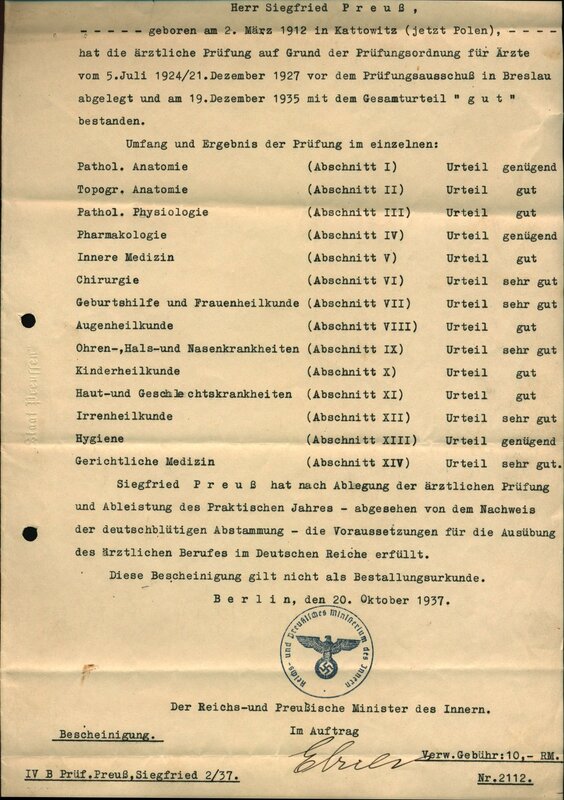

The concept of belonging to a nation had become rendered essentially meaningless. Over the following years, Jews began to face increasingly strenuous restrictions in their social, economic, and work lives. For instance, they were forbidden to enter particular areas like swimming pools or theatres (“Timeline” 14). Preuss himself was denied an appointment as a physician simply because of his ethnicity (J. Preuss 8; see the image to the left). After the Nuremberg Laws, another group of anti-Jewish laws were passed that essentially restricted the Jews from participating in the German economy, making it legal, for instance, to confiscate their property (“Anti-Jewish Legislation” 2).

Unlike Preuss, many Jews did not emigrate from Germany, partly because the Nazi “regime’s intentions were not immediately clear” until it was too late (Gellately and Stolzfus 8). At this point, Jews were becoming increasingly disenfranchised and faced a number of restrictions on their freedom of movement and employment (Meinecke and Zapruder 29). Moreover, the fact that many Jewish people’s businesses and properties were taken from them resulted in their increasing impoverishment, which made it difficult to immigrate to a new nation (Gellately and Stolzfus 8). For instance, in the case of Preuss, he had to gain a substantial monetary grant in order to be allowed to immigrate to the United States (48). Jewish doctors like Preuss were also forbidden to practice on “Aryan” patients (Meinecke and Zapruder 27). Preuss recalled that this happened after he left, stating that while he was an intern at the Jewish Hospital in Hamburg, “we could treat everybody, and the hospital was still open to non-Jewish patients” (49 – 50). Measures against the Jews became more horrific after the war started, but that is not the focus of this particular page.

Return to "Home" Continue to "Becoming an American Citizen"

Works Cited

“Anti-Jewish Legislation.” Shoah Resource Center, Yad Vashem, www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%205741.pdf.

Confino, Alon. A World Without Jews: The Nazi Imagination from Persecution to Genocide. Yale University Press, 2014. ProQuest Ebook Central, ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/lib/uvic/detail.action?docID=3421401.

Fraser, David, and Frank Caestecker. “Jews or Germans? Nationality Legislation and the Restoration of Liberal Democracy in Western Europe after the Holocaust.” Law and History Review, vol. 31, no. 2, 2013, pp. 391 – 422. Cambridge Core, doi: 10.1017/S0738248013000035.

Gellately, Robert, and Nathan Stolzfus. “Social Outsiders and the Construction of the Community of the People.” Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany, edited by Robert Gellately and Nathan Stoltzfus, Princeton University Press, 2001, pp. 3 – 19.

Rosenhaft, Eve. “Blacks and Gypsies in Nazi Germany: The Limits of the ‘Racial State.’” History Workshop Journal, no. 72, 2011, pp. 161–170. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41306842.

Meinecke, William, and Alexandra Zapruder. Law, Justice, and the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2014. case.edu/law/sites/case.edu.law/files/2020-06/Reading%20Materials%20PDF%20small.pdf.

Preuss, Fred. Remembering. University of Victoria, 2018.

Preuss, Jennie. Biographical Sketch. Remembering, by Fred Preuss, University of Victoria, 2018, p. 8.

Salwin, Lester. “Uncertain Nationality Status of German Refugees.” Minnesota Law Review, vol. 30, 1946, pp. 372 – 394. The University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository, core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217207297.pdf.

“Timeline of the Holocaust.” Emergency Librarian, vol. 24, no. 5, 1997, pp. 13 – 15. Gale OneFile: CPI.Q, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A30070184/CPI?u=uvictoria&sid=CPI&xid=92f28326.