Return to "Home" Continue to "The Nuremberg Laws"

Life in Germany

Medical School in the Early 1930s

When Fred Preuss started medical school at the University of Breslau in 1930, Hitler had not yet become chancellor. However, Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933 was quickly followed by progressively discriminatory measures enacted against the Jews and other marginalized groups. German Jews lost their full citizenship in 1935 via the passage of the Nuremberg Laws and became “subjects” of the German Reich instead (K. Preuss 13). This page will discuss how these antisemitic policies affected Preuss’s experiences in medical school.

During 1930, when Hitler had not yet come to power but was actively promoting his party, things were relatively “good” for Preuss. As Preuss himself stated, “[w]e were fortunate that Breslau was fairly peaceful and Nazism, in the beginning at least, at the university was not as violent as in some other schools” (45). Things did not stay “fairly peaceful” for long. Preuss describes reading the newspapers discussing Nazi violence, noting that the situation became increasingly “uncomfortable for the Jewish students” at his university (45). Preuss noted a distinct change in attitude towards the Jews after Hitler came to power in 1933, which he discusses in the audio clip below.

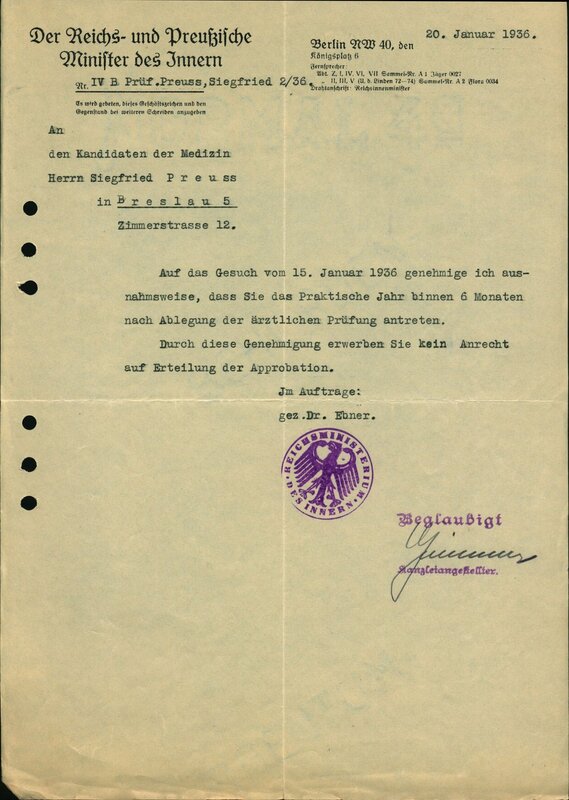

This discrimination against the Jews became legitimized even further by the passage of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935. Despite the fact that he had finished all the coursework for his medical doctorate, Preuss was denied his doctorate in Germany, simply because he could not prove his “Aryan” heritage, which he discusses in the audio clip below.

By demoting them to subjects, the Nazi regime could “legally” discriminate against German Jewish nationals and deny them their natural rights. It is almost unthinkable to consider not being able to obtain a degree simply because of your ethnicity. This, however, was what Preuss faced in Nazi Germany (46 – 47).

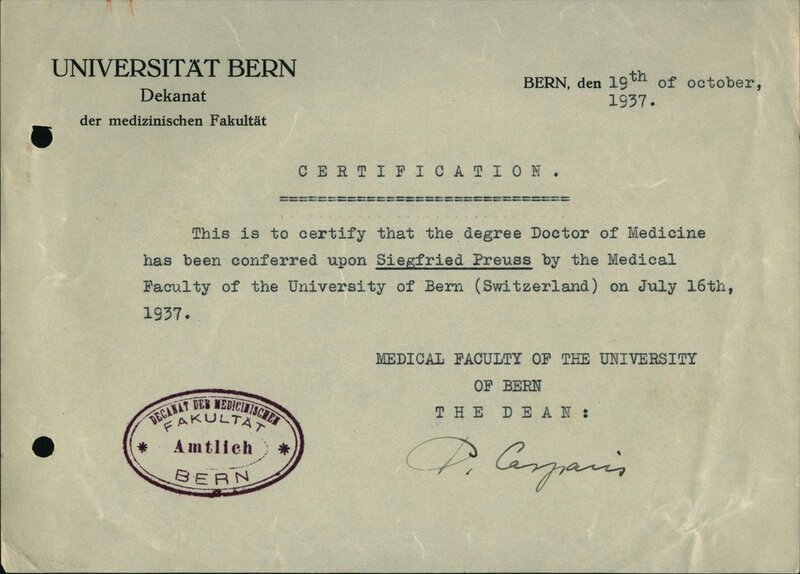

Acquiring a Doctorate at the University of Bern

At this point, Preuss was quite certain that he wanted to immigrate to the United States. He said that people were allowed to practice medicine in Germany without their final credentials, but he decided this would be unwise, as it would limit his likelihood of being hired. Moreover, considering his eventual plans to move to the United States, he thought it would be best to obtain his doctorate in Europe beforehand (46). This being the case, Preuss decided on a different means of acquiring his MD. After learning he could receive an MD from the University of Bern in Switzerland if he took three relevant exams and one additional course, he obtained a visa to study there (47). He described his time at the University of Bern as “very enjoyable” (47), although from our current perspective, this was likely at least in part because it served as a respite of sorts from his life in Germany. Between attending classes and taking exams, he “made trips to the Swiss Alps, to Swiss cities, [and] swam in the river” (47). After one semester, he received his MD from the University of Bern in 1937 (K. Preuss 13).

Decision to Move to the United States

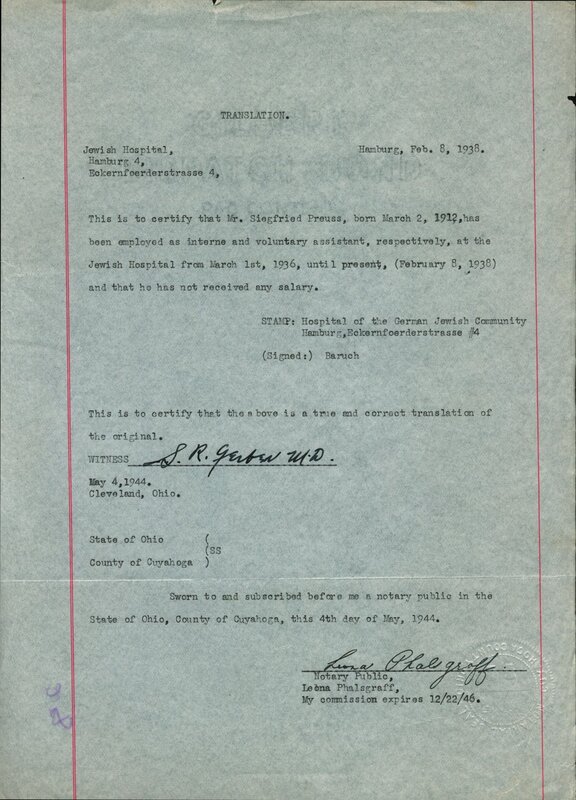

Preuss now faced a new challenge. He needed to obtain a visa so that he could leave Germany and immigrate to the United States. This was not an easy task. To start with, he had to move back to Germany, as, in his words, “I had no place to go -- I went right back into the lion’s den” (47). This description of Nazi Germany seems very apt, given that this was the nation that had rendered his citizenship essentially meaningless and denied him the right to obtain his MD (47). He completed an internship at the Jewish Hospital in Hamburg and took lessons in English while awaiting his American visa (47, 51). Actually acquiring this visa required a lot of effort on Preuss’s part. First, he needed to obtain an affidavit from a distant relative in the United States essentially certifying that he, as an immigrant, “would not become a charge of the American system” (47). However, Preuss had difficulty getting in contact with this relative, until, by some stroke of fate, he learned that someone he knew was travelling to the United States. Preuss asked this person to pressure his relative to send the affidavit, which he eventually did (47). This was still not sufficient to obtain his visa.

With the help of another medical doctor he was acquainted with, Preuss was able to get in contact with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), who managed to arrange for him to obtain a monetary grant upon arrival in the United States (47 – 48). After two years, Preuss was finally granted a visa and arrived in the United States in 1938 (48). The pressure of Preuss’s position is somewhat hard to conceptualize now, but Preuss no longer had any of the rights and protections that should be due to citizens. Preuss explains some aspects of this situation in the audio clip below.

In essence, he viewed himself as trapped in his own country, namely because of the growing persecution of the Jews and the fact that any protection granted citizens had been taken from him. He even had the legitimate concern that his ability to leave a country that no longer fully acknowledged him would also be taken away.

Return to "Home" Continue to "The Nuremberg Laws"

Works Cited

Preuss, Fred. Remembering. University of Victoria, 2018.

Preuss, Karl. Introduction. Remembering, by Fred Preuss, University of Victoria, 2018, pp. 10 – 13.