Hands A&B: Reconstructing an August Afternoon in 1703

Matthew loosened his neck cloth and then directed his attention back to the book upon his desk and read for the third time...

But for so much as some will object, that Augustine in the words afore rehearsed, doeth not speake of eating the Sacrament, for the text of the Scripture, upon which he dooth ground, is not spoken by eating the Sacrament…

He let his gaze roam out the open window of his study and across the field, now summer-parched, to the woods beyond. He remained in this way for how long he knew not, but returned to himself at the sound of a small voice in the room.

His daughter Margaret — whom they all called Maisie — stood in front of his desk and repeated: “The rent in your stocking is mended.” As she waited for his reply she passed her toy ball, a pig’s bladder, from hand to hand.

“Thank you, Maisie. I am glad of it.”

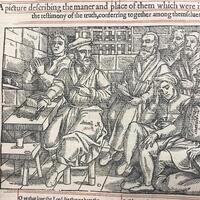

Matthew expected her to go. As a rule, she spent little time in his study, but there she remained. It took a moment for him to realize that she was staring fixedly at the open volume of Foxe’s Acts and Monuments.

“Who are those men, Father?” she asked and pointed to a woodcut of suffering martyrs.

“They were good men. Christian men.”

“Do they live near here?”

“No, Maisie, the Lord gathered them to Him many years ago.”

“Why are they in your book?”

“That we might remember them and their bravery.”

Margaret considered this information. “If they were not in the book then were they forgotten?”

He turned the book on the table so that it faced her. “Another good man has written their lives so we might learn of them something and remember.”

“He must be very aged who wrote it,” she decided.

“Why do you say so?”

“It should have taken him ages to write so many words. It should take me a year just to read it. And writing is slower than seeing.”

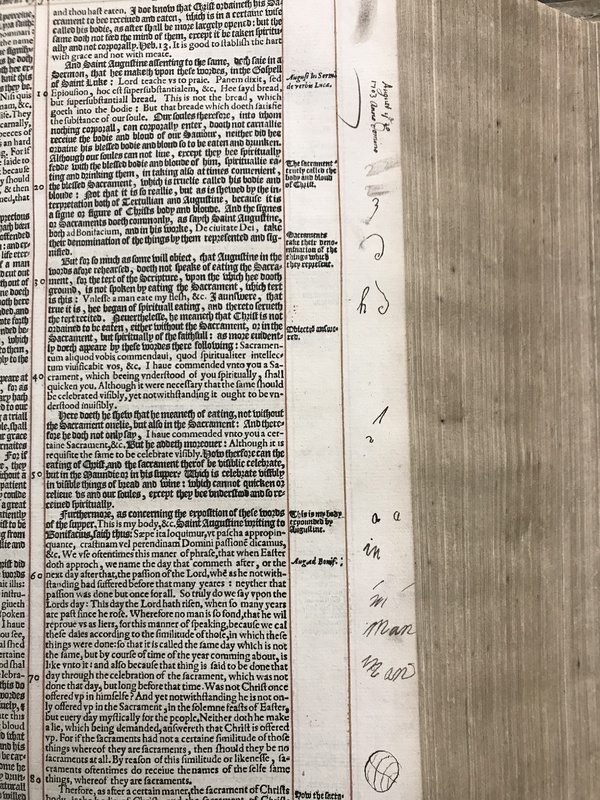

Matthew laughed and then took up his quill in his right hand, dipped it in ink, and, leaning across the book, wrote the month, date and year in short order. He concluded this virtuoso display with a small flourish beneath the words 1703 Anno Domini.

Margaret laid her ball on the desk and applauded enthusiastically.

“Would you like to try? I know you have practiced your letters.”

She looked unsure, so he came around the desk and sketched a 2. “Now you try it, Maisie.”

He dipped the quill once more in the ink, tapped off the excess, and passed it to her.

Margaret leaned over the page and slowly, with her tongue held between her teeth, produced a reasonable facsimile of the 2.

“Good,” he said and smudged away the numbers with his thumb. “Now, a three. Go ahead.”

She sketched an admirable 3 and turned to him, beaming.

“Do you see? It’s not so hard.”

“But numerals are easy,” she objected. “It’s the letters are hard. They are so…loopy.”

She swirled the tip of the quill in the air for emphasis. He took it from her and drew a simple curl and then encouraged her to copy it — which she did with limited success.

Then he drew an H, loop and all, but she hesitated. He guided her hand and told her to move her arm and not her wrist, and they practiced a short stroke and wave. Next, he had her copy an A.

“Very good. Shall we try ‘man’?”

“I am not skilled at M. ’Tis my downfall.”

“Come. M is the simplest of letters — and the first in your own name. You must learn M.”

He sketched an M and as he scribbled he remarked, “Like small waves on the sea.” But Margaret remained skeptical.

Once more he guided her hand and spoke the letters aloud as they produced them. “M…A…N. Man. On your own, now.”

She took a deep breath and then laboriously wrote man, only exhaling as she lifted the quill from the page.

“Very good, Maisie. Here now, hold up that ball.”

Margaret did as instructed and Matthew doodled a rough approximation of the pigskin.

She clapped again and asked, “Will you come play with me? Can we play for a while?”

Matthew looked at his daughter, then out the window once more. It was a glorious summer day and he knew that such days were not many in life.

“To every thing there is a season,” he quoted, and with a rueful glance at the open book on his desk, he took the ball and led her out.

“Father, will we ever be in a book, or will we be forgot?”

In the now empty room, Volume II of Acts and Monuments lay open to page 1031. Outside rang the sound of laughter as the ink dried on the unturned page — unremarked and forgotten.

FACTS behind the FICTION

We do not know the names, age, or sex of the two individuals who wrote in the margins of page 1031 (though the name Matthew is written in the same handwriting on page 1539). With no additional information, we can only identify them as Hand A and Hand B. But that does not mean that the scenario above is solely a work of imagination. Through analysis of the “clues” in the marginalia itself we can deduce a great deal about what went during those few moments of scribbling.

Hand A was right-handed. We can see this because his work is crisp and free of smudges —something much easier to control when the hand holding the quill moves in advance of the wet ink, rather than following behind it. The placement of the date at the upper-corner, given the size of the book, could only practically have been written by someone standing at the top of the page. Had this individual been left-handed, or had they been writing while standing to the right of the book, then the bottom of the script would face the edge of the page.

The sketch of ball looks quite similar to similar artifacts in museum collections.

We know that after the writing practice ended, the book was left alone for some time because the page was not turned — as evidenced by the lack of ink stains on the opposite page. The ink had fully dried before either the book was closed or the reader made it to page 1032.

We do not know the names of Hands A and B, but we do have a glimpse into a charming domestic moment that would otherwise have passed through history unremarked and forgotten.