To the Most Learned and Excellent Reader of these Omeka Pages

For whom the following information has been set down in accordance with the profestations of the almighty true following of the creators of this true history of John Foxe's Actes and Monuments (1610)

in which a central element of textual control is employed in the presence of prefaces and paratexts which the following page shall address. Below you shall find all manner of introductory information regarding the use of textual elements aside from the main text of Acts and Monuments and the implied reader that such paratexts invoke. It is this author's great pleasure to welcome you, dear reader, to this Omeka page, and to invite you at your leisure to peruse this and the diverse other pages here available regarding the University of Victoria's copy of the sixth edition of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments.

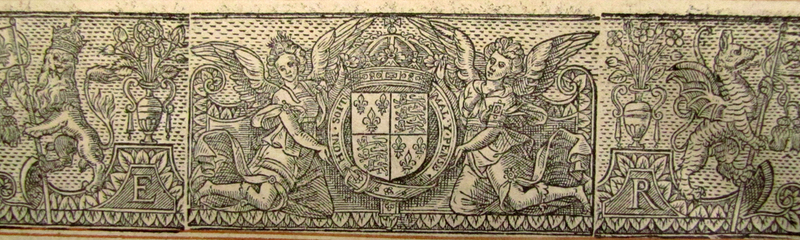

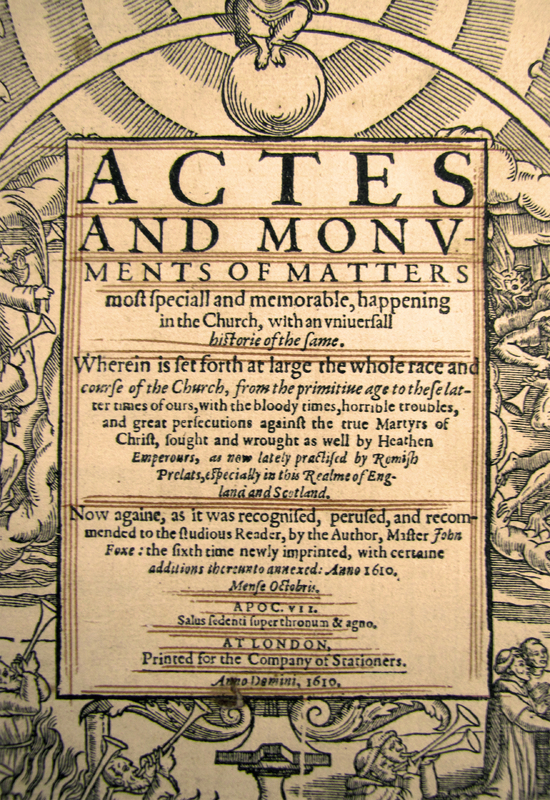

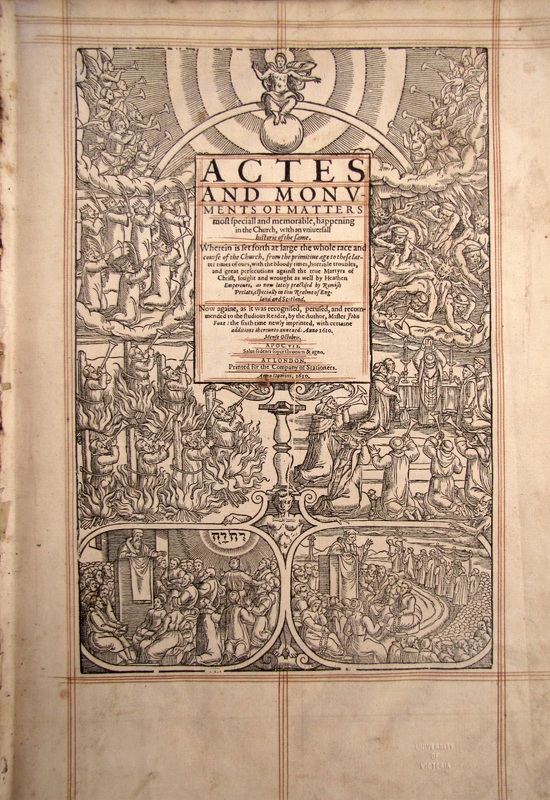

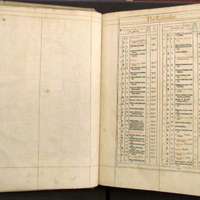

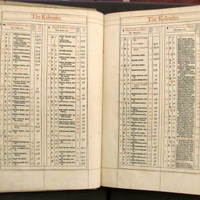

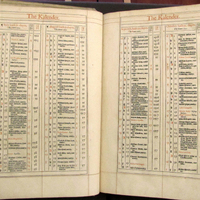

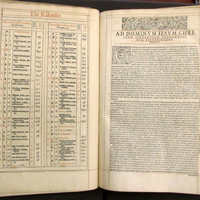

The 1610 edition of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments is the sixth major edition of the text to be published. Compiled after the deaths of both Foxe and his printer John Day, the opening pages of the first volume of the 1610 edition begin with a good deal of paratextual material (which I will define below) drawn from the first four complete editions of the text (1563, 1570, 1576, 1583). Prior to the main text of the book, readers are met with, in order, a title page, a calendar of martyrs, a dedication to Christ (in latin), a dedication to the Queen, a preface for the learned (in Latin), a preface for the unlearned, a preface declaring how the book should be read, four questions for followers of the Pope, four considerations for protestants, and a series of poems. Although the dedications to Christ and the Queen, along with the Latin preface to the reader and the preface declaring how the book is to be read, were present in the first edition of Acts and Monuments, the other paratextual material was introduced and edited — changed and renamed — throughout the following editions. This introductory material represents a reader's presumed first point of contact with the text and as such provides valuable insight into how Foxe, Day, and the 1610 compilers intended the text to be read. For not only do the paratexts address actual readers, but they also construct implied readers while attempting to shape the way in which those readers receive the text. They both welcome readers to the world of Acts and Monuments and prescribe the rules by which visitors to this world must live.

An Introduction to Paratexts

Paratext is a term coined by French literary theorist Gerard Genette who includes a large list of extratextual elements — i.e., elements of the book that are not the core text of the book — in his definition of the term. Genette includes all of the following elements in that list: "a title, a subtitle, intertitles; prefaces, postfaces, notices, forewords, etc.; marginal, infrapaginal, terminal notes; epigraphs; illustrations; blurbs, book covers, dust jackets, and many other kind of secondary signals, whether allographic or autographic" (Palimpsests 3).

Genette notes that these elements of a text serve a variety of purposes important enough to be considered their own distinct literary styles. For example, Genette suggests that both prefaces and titles have so great an effect that they may rightfully be considered their own genres (Palimpsests 8). Genette has proposed that among the many uses of various paratexts, the key aims are to present information, to impart authorial or editorial intention or interpretation, and for the text to "make a book of itself and [propose] itself as such to its readers" ("Introduction" 261, 268). By presenting readers with a title page, dedications, and an introductory salutation, the author and editor (and, in our case, the 1610 compilers) provide a kind of welcome at the front door of the text and an invitation to come in. Readers are told what they are reading, from whom it comes, its purpose, and how their role as readers shall be defined.

Furthermore, and key to the discussion of paratexts here, they provide a sense of the implied readers of a text. To whom a preface is addressed, how it is phrased, and which paratexts are included all provide clues as to whom the author originally intended as an audience for the work. Given the nature of how paratexts are used within the 1610 Acts and Monuments it is generally assumed that this book was meant to be received by as many readers as possible.

The Implied Reader

The Common Illiterate Masses

"the simple flock of Christ especially the unlearned sort, so miserably abused,

and all for ignorance of history, not knowing the course of times"

The above phrase from "To the True and Faithful - Page 1" (which can be seen in its entirety below) perfectly captures John Foxe's impression of the common folk to whom he addresses his work. They are "simple," "unlearned," "miserably abused," and ignorant folk who Foxe aims to educate on the glory of the English Church. In his dedication to Queen Elizabeth, he iterates the same, stating that he has written his text in "the popular tongue" for the sake of "the ignorant flock of Christ . . . long led in ignorance, and wrapped in blindness . . . [because he] thought but that such should be helped, their ignorance relieved, and simplicity instructed" (see "To the Right Virtuous Queen - Page 2," below). It is widely accepted that the intended audience for Foxe's work has been, at least since its second edition, the broad masses of common folk (Felch 58), in whom Foxe hoped to stir up a sense of protestant zeal. Susan Felch notes that although the paratext of the initial 1563 publication of Acts and Monuments was dedicated to apologizing to the readers most likely to discount his work (57), subsequent editions were "clearly directed . . . towards a lay readership" (58) with a commitment to education (62). This sentiment is supported by the work of such scholars as Warren W. Wooden and Meghan Nieman who use this presupposition to position their arguments that the text is directed to both child and female readers respectively, and who I will cite in the sections below.

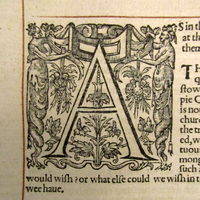

That the text was intended for wide readership among the common people has also been well asserted by John King, whose explorations regarding the fonts and typefaces chosen by Foxe and Day has led him to conclude that the choices made there were highly deliberate aims to make the text as accessible as possible for vernacular readers (185). King notes the use of black letter, or gothic, type (see example on the right) with editorial awareness that this font was considered that of common English text (177-78). King also notes what he calls an "uneasy acknowledgement" in the Latin preface "Ad Doctum Lectorem" in which Foxe addresses the learned reader, stating that the book is not written in Latin because the needs of the people dictate that he uses the common vernacular instead (178-80). Felch, too, finds that the editorial material of Reformation books (including, of course, Acts and Monuments) depicts an authorial anxiety "regarding the issue of interpretive coherence" (55). That is, she suggests that the prefaces and marginal notes point to an effort by Foxe "designed to assist the simple reader towards simple understanding" (55). In this way, it is clear that Foxe's paratext is specifically aimed at educating the common reader on how to read his text.

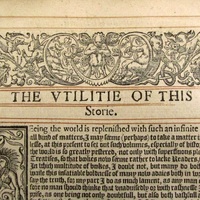

To this point, as I note above, Foxe acknowledges this aim to educate [indoctrinate] the common folk in his dedication to the Queen, stating that the text is "written in the popular tongue" not for the Queen's "own peculiar reading, nor for such as be learned" but for "the necessity of the ignorant flock of Christ" (see "To the Right Virtuous Queen - Page 2," below). He reaffirms this statement in a following paratext titled "The Utility of this Story" where he tells the common reader that with "diligent consideration and special regard of the common utility which every man plentifully may receive by the reading of [the] Monuments or Martyrology" he has written "in that tongue which the simple people could well understand" (see "The Utility of This Story - Page 1," below). By the time of the inclusion of these prefaces, Foxe was aware that the bulk of his readership consisted of the common folk, and with this in mind, the paratexts all pointedly aim at guiding this common reader to the reading of history that Foxe endorsed in his Acts.

That the text was intended for wide readership among the common people has been well asserted by John King, whose explorations regarding the fonts and typefaces chosen by Foxe and Day has led him to conclude that the choices made there were highly deliberate aims to make the text as accessible as possible for vernacular readers (185). King notes the use of black letter, or gothic, type (see example on the right) with editorial awareness that this font was considered that of common English text (177-78). King also notes what he calls an "uneasy acknowledgement" in the Latin preface "Ad Doctum Lectorem" in which Foxe addresses the learned reader, stating that the book is not written in Latin because the needs of the people dictate that he use the common vernacular instead (178-80).

The Woman Reader

Meghan Nieman provides an excellent investigation on the impact that Acts and Monuments would have had on the woman reader. In her essay titled "Foxe's Female Martyrs and the Utility of Interiority," Nieman emphasizes the efforts of the "Utility" preface to control the reader's perspective while engaging with the text. Positing that the use of the common vernacular implies the expectation the text will be read aloud to an audience that would include women (298). Nieman further notes the middle- and working-class status of the female martyrs in the text and finds that the instructions in the preface to see martyrs as a reflection of themselves suggests that the text is directly addressing itself to middle-class women (297-299). Concluding that "each edition of Acts and Monuments increasingly resembling a manual on how to read, and an author intent on shaping his readers," (296) Nieman concurs with Genette regarding the power of prefatory material. Although Foxe's prefaces specifically address a male reader citing, for example, the "common utility which every man may plentifully receive by the reading" (emphasis added, see "The Utility - Page 1," below), he by no means precludes the notion of women in the reception of his book. It was not common to address a female reader in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and that Foxe more frequently addresses the generic "reader," suggests again that this text was meant to be received by as broad an audience as possible.

The Child Reader

Children have been posited as a potential target audience for Foxe and Day by Warren W. Wooden, whose compelling case similarly draws upon the presence of paratext as a method employed to make the text palatable for young readers. Wooden argues that, in fact, Acts and Monuments was particularly tailored for "the interests and capacities of the young readers who would one day have to preserve England from the powers of darkness" (87). Wooden, as with most scholars, finds no issue with the assumption that Acts and Monuments was intended to exert mass appeal and suggests that this quality of the text is closely associated with the field of children's literature (74). Wooden asserts that in order to draw the child reader in the author includes scores of illustrations and "simple, pithy, often humorous" marginal scholia (75) (see right for an example of such marginal work). Although these inclusions may have had the illiterate masses in mind, there is no doubt that such simplifications of the book's material would prove as valuable tools for the adult wishing to instruct their child.

The Papists

"To you all and singular which profess the doctrine and religion of the Pope . . .

pretending the name of Catholics, commonly termed Papists"

In addition to the protestant masses to whom Foxe addresses his work, a good deal of prefatory material is dedicated to the "Professed friends and followers of the Pope's proceedings" (See "Four Questions - Page 1," below). Foxe begins his general address to the reader in "To the True and Faithful Congregation of Christ's Universal Church" with nearly a full page of text defending his work from the attacks of offended Catholics. Foxe, in effect, makes a martyr of himself at the outset of his address to the common protestant reader, calling himself a "sinful wretch" and stating that his work intended for the "advancement of [God's] glory, and profit of his church" was met with the prating, finding of fault, destruction, and abuse of "stinging Wasps and buzzing Drones" (see "To the True and Faithful - Page 1," below). Foxe sets up the Papists as "accusers" and oppressors who "many times deprave good doings" with their "slandering tongues" (see "To the True and Faithful - Page 1," below). He treats them as enemies and establishes them as the persecutors whose persecution validates his "history" of martyrdom by making a martyr of Foxe himself.

However, although Foxe establishes the Papists as slanderous enemies to his cause, he also appears to be aiming at some level of conversion in his dealings with them. That is, his own slander of the Papists seems aimed not simply as a redoubt against his accusers, but also as a rhetorical appeal to emotion of the unlearned Papist reader. As Susan Felch puts it, Foxe "expresses his hope that by recounting their bloody deeds in accurate detail, but with a moderate tone, they will be brought to wash their 'bloudy handes with the teares of plentiful repentance" (58). Foxe aims to inspire a guilty conscience in Papist readers as, for example, he lists a damning history of the Catholic Church and then asks "[w]hat need then any more witness to prove this matter, when you see so many years ago whole armies and multitudes, thus standing against the pope?" (see "To the True and Faithful - Page 4," below). In his prefatory material, Foxe establishes the wrongdoings of the Papal Church and aims to instill a sense of question in the reader — that is, he aims to have the Papist reader question whether their faith is correct.

To this end, Foxe furthermore addresses an entire paratextual section of four rhetorical questions to the Papist reader. Foxe's questions are phrased without expectation of response, framed rather as accusations of the Catholic Church in order to establish the Pope's Church as a sinful one. For example, the first of Foxe's questions is not even phrased as a question. Rather, Foxe states: "How the Church of Rome can be answerable to this hill of Sion: seeing in the same Church of Rome is, and hath been now to many years such killing and slaying, such cruelty and tyranny shewed, such burning and spilling of Christian blood, such malice and mischief wrought, as in reading these histories may to all the world appear" (see "Four Questions - Page 1," below). As Felch notes of the questions, "the intent is clearly to provide the factual information necessary to train a responsive reader" (63) and educate "morally sensitive readers" (60). It can be readily assumed that Foxe's questions are not the sort which expect an answer, suggesting that, although the loyal Papist is the addressed reader, this paratext may, in fact, be present for the sake of the shaken Papist — the Papist capable of being swayed to Foxe's Church of England.

In Conclusion

It has been noted that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries prefaces were the last parts of a book to be printed (Voss 735) and indeed the prefatory material in this edition has the feeling of an afterthought. With no significant new material — e.g., there is no new dedication to King James, the monarch contemporary with the printing of this edition — the prefaces of the 1610 Acts and Monuments are simply a new ordering of old material. However, as this material was not omitted entirely, the significance of its presence remains.

Although the cost of this book would have been great, thus limiting the common person's ability to obtain a copy, accessibility to its text was foremost in the minds of Foxe, Day, and the 1610 compilers. The book was made available to the public in cathedrals and parish churches (Wooden 73), and the inclusion of paratexts such as the many woodcut images and pithy marginal scholia ensured that even the least literate of readers could find some part of the book accessible to them. The truth of Foxe's assertions that he intended for the audience of this text to be the common masses is clear, and, although one could certainly take issue with the text's overt attempts to control the reader, one may, at the very least, accept that Foxe truly did aim to educate "the unlearned sort, so miserably abused . . . for ignorance of history" ("To the True and Faithful - Page 1").

Foxe invites his readers to "first peruse, and then refuse: measuring the untruths of [his] history . . . according as [they] find, and so to judge the matter" ("To the True and Faithful - Page 1"), and I invite you, dear reader of these Omeka pages, to do the same. And if you should find your "labour too much in reading [these stories], [your] choice is free either to read this, or any other which [you] more mindeth" ("To the True and Faithful - Page 1"). But know that by engaging with these Omeka pages on the 1610 edition of John Foxe's Acts and Monuments, you too, dear reader, have become one of the many lives touched by

Paratextual Gallery

Works Cited

- Appel, Markus, and Barbara Maleckar. "The Influence of Paratext on Narrative Persuasion: Fact, Fiction, or Fake?" Human Communication Research, vol. 38, 2012, pp. 459-484. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2012.01432.x.

- Genette, Gerard. "Introduction to the Paratext." Translated by Marie Maclean, New Literary History, vol. 22, no. 2, 1991, pp. 261-272. JStor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/469037.

- ---. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky, University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

- ---. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin, Cambridge UP, 1987.

- King, John. "Foxe's Book of Martyrs and the History of the Book." Explorations in Renaissance Culture, vol. 30, no. 2, 2004, pp. 171-196. Brill, doi:10.1163/23526963-90000283.

- Nieman, Meghan. "Foxe's Female Martyrs and the Utility of Interiority." Dalhousie Review, vol. 85, no. 2, 2005, pp. 295-305. http://hdl.handle.net/10222/61567.

- Singman, Jeffrey L. Daily Life in Elizabethan England, Greenwood Press, 1995.

- Stephens, W. B. "Literacy in England, Scotland, and Wales, 1500-1900." History of Education Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 4, 1990, pp. 545-571. JStor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/368946.

- Voss, Paul J. "Books for Sale: Advertising and Patronage in Late Elizabethan England." The Sixteenth Century Journal, vol. 29, no. 3, 1998, pp. 733-756. JStor, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2543686.

- Wooden, Warren W. "John Foxe's Book of Martyrs and the Child Reader." Children's Literature of the English Renaissance, edited by Jeanie Watson, University Press of Kentucky, 2014.