Ghetto Money

Julius Maslovat's Story

Yidele Henechowicz was an infant when his mother threw him over a barbed wire fence to his father. Little did they know that that would save him from his mother's fate at Treblinka extermination camp.

Yidele was transported from where he was born in Piotrkow, Poland in a closed cattle car to Buchenwald. One of the few memories he retains from his childhood is that of an open air cattle car, which transported him from Buchenwald to near-by Weimar. Buchenwald was the last place that he saw his father.

At two-and-a-half, Yidele was Buchenwald's youngest prisoner. He was then transported in a passenger train to Bergen-Belsen, the notorious camp where Anne Frank and her sister were murdered. But Yidele was lucky; two women cared after and protected the children, and somehow he survived until the British Army liberated the camp.

After liberation, Yidele was adopted by a Swedish couple from Helsinki, and renamed Julius Maslovat.

Now, Julius lives in Victoria BC. Due to his very young age at the camps, he has very few memories of that time--the main one being the cattle car. Through documents, photographs, documentary footage, and long-lost family members, Julius has been able to reconstruct his forgotten past.

The Ghetto Money

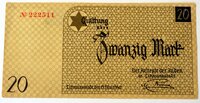

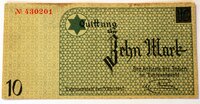

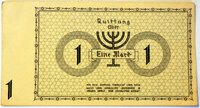

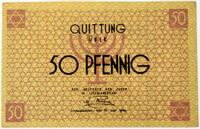

One of the objects Julius has held on to is an envelope of ghetto money. Placing that envelope on the table of the public library's study room, he takes out the five bills from the plastic sleeve he stores them in. One by one, he passes them over--a Zwanzig (20) Mark bill, Zehn (10) Mark, Fünf (5) Mark, Ein (1) Mark, Fünfzig (50) Pfennig. He also takes out two coins, a 5 and a 10 Mark. The bills are all in surprisingly good condition; crisp, whole bills that show little wear and tear, despite the date that they all bear.

They are made of light paper, much thinner than expected, but that's unsurprising. They're ghetto money from the Litzmannstadt Ghetto, in what is now present-day Łódź, Poland. And ghetto money, distributed by the Germans to the Jews, was not made to last.

Little is known about the provenance of these objects before they came into the possession of Julius. With odd specificity, the bank notes, as is stated, were printed on 15 May, 1940. The coins were struck later, made with aluminum or an aluminum/magnesium alloy in 1943, both specifically issued to the Ghetto in ‘Litzmannstadt,’ (today Łódź) as is denoted on the bills themselves. We do not know who (which particular person) oversaw the printing and minting of this currency, who oversaw its distribution, and whose hands this money passed through in the Ghetto, if it made it there at all.

The tale of these bills beyond their initial issuing in Łódź begins in Helsinki, Finland, not with Julius but with an unknown and unnamed individual who used this money to pay a debt. Julius’ adoptive father, Samuel Maslovat, was a lawyer and often accepted alternative forms of payment for services; in Julius’s words, "it's how he got a stamp collection."

In this particular case, however, it was the Ghetto money that was given to him as payment for services rendered. Beyond this there is little information available. The objects then resided with the Maslovats in Finland before eventually being handed down to Julius by his adoptive father, landing it in its current home in Victoria, British Columbia.

Since becoming property of the Maslovats, the notes have been stored safely inside a plastic sleeve to prevent rips and tears, and still further inside of a paper envelope which has prevented any kind of light damage.

Julius has little connection to these bills, rather he hangs onto them as a temporary caretaker, a role previously assumed by his father, until such a time as he finds a suitable museum or archive to which the objects can be donated and enrolled.

What do these objects represent?

What do these objects represent? To explore this concept you are invited to consider the currency that you may or may not have in your own wallet.

Traditionally, money has been used as a conveyor of national symbolism. In Canada’s case, the nation’s coins boast an array of national symbols; from the lowest circulation coin to the largest, images featured on the reverse have been specifically chosen to represent Canadian culture and identity.

The beaver-graced 5 cent piece is indicative of the fur trade upon which settlement, and thus the nation, was initially predicated, whilst the Bluenose whisking its way across the reverse of the 10 cent piece, is, according to the Royal Canadian Mint, “meant to symbolize both the magnitude of the fishing industry in Canada and the maritime skills of Canadians.” The various caribou, loons, and polar bears that make their homes on the other three circulation denominations all in turn serve to symbolize the vastness, and wilderness of Canada from sea to sea to sea.

And on the obverse? A portrait of Her Majesty, the Queen of Canada (or the reigning monarch of the day). A symbol of the nations past and of its present. The names which have been granted to the one and two dollar coins the 'loonie' and 'toonie' respectively, is, in and of itself, a unique expression of Canadian identity and pride.

Canadian bank notes similarly portray any number of different scenes from Birds of Canada, to Canadian Journeys, to the Frontiers each denomination sporting, until recently, the portrait of a great Canadian statesmen: Prime Ministers MacDonald, Laurier, Borden, and King all grace common circulation notes. The Royal Canadian Mint also, multiple times a year, releases special edition coins with unique images representing historic or culturally significant scenes presented on the reverse.

Canada, of course, is not the only nation to do this. Germany mints its euro with an image of the Brandenburg Gate; Austria with Gentian, Edelweiss, and Primrose gracing the lower denominations, historic buildings on mid-ranged denominations, and persons of note (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Bertha Von Sutter) on the 1 and 2 euro coins; much in the way that all EU states maintain cultural autonomy over their currency.

This is a trait that has been manipulated in the creation of this Ghetto Money. While there are symbols of the Jewish faith--a star of David and a menorah--present on both the coins and the notes, this currency is devoid of any national sentiment. Jews are no longer Polish, German, Austrian or otherwise; rather they are reduced to the Jewish other.

These objects were created to isolate. To isolate Jews from their national communities, their national identities, and to isolate them more generally from participation in the wider economy of occupied territories. Outside of Ghetto walls, this money was meant to be useless, made of cheap materials and not intended to last long.

And yet, in a strange twist of fate, and perhaps in a moment of profound resistance, these objects found their value in an outside economy when traded to Samuel Masolvat in return for legal council sometime after the war had ended. What is certain, is that the creation of this currency shows the clear intent to isolate and strip identity from the Jewish other as early as the spring of 1940. As Julius pointed out, this currency is representative of minute detail put into the planned mass Ghettoization of entire populations.

Historical Background

Beginning in 1939, Nazi Germany began to concentrate and isolate Jewish populations in ghettos which were specifically designed to remove Jewish communities from the broader social structure of occupied territories. A part of this policy of concentration and isolation was the issuing of location specific currency to cut Jewish populations from the general national and international economy. According to the Montreal Holocaust Museum, the Judenrat, or Jewish council that administered the ghettos (under the supervision of Nazi authorities) were responsible for issuing a currency specific to each ghetto.

The Łódź Ghetto, from which these objects originate, was the first to issue such currency. According to the Virtual Jewish Library, Chaim Rumkowsky, a Jewish elder put in control of the Łódź ghetto by German authorities, was instructed to design and implement a ghetto specific currency. Rumkosky in turn passed this task on to the artist Wincenty Brauner.

However, the designs that Brauner submitted would ultimately be rejected by German authorities, who citied the subversive nature of the designs for their decision. As a result, Pinkus Schwarz was instead chosen to produce a design for the notes; this is the design that can be seen on surviving notes today.

The money was popularly referred to as "rumki" or "chaimki," after Chaim Rumkowsky.

By the end of the war, with hyperinflation setting in, Ghetto Money (both notes and coins) became valued more as a source of fuel than they were as a form of currency, as they were made of hyperflammable paper and metal alloys.

Reduction and Resistance

The money seen in this exhibit is not stripped of its Judaic symbolism; notably the Star of David and Menorah, which are present on each of the notes and coins. While it it is well known that Nazi Germany sought to strip Jews of their national identities and reduce them simply to the Jewish other — as is clearly demonstrated in the unveiling and enforcement of the Nuremberg laws and other anti-Jewish ordinance — the survival of Jewish symbolism allowed for the survival of an identity.

That Judaic identity, deemed inferior by the German state, ultimately allowed Jews as an ethnic group (rather than any one national group) to resist German attempts at cultural extermination. The fact that two prominent cultural and religious symbols were not only designed, but allowed to be printed on this currency points to a desire amongst the artists and the Jewish council to maintain a Jewish identity. While a small act, the preservation of these symbols and their meaning flew in the face of Nazi ideology and policy in regard to the total extermination physically and culturally of the jewish other.

The fact that these particular notes then found value after the war adds a unique significance to these objects in regard to their ability to rebuke, and lived experience in rebuking, national socialist ideology both during and after the war.

Conclusion: Speculative Histories

While we have done our best to piece together the trajectory and history of these objects we have been unable to determine every aspect of their provenance. We know that Julius received these objects from his adoptive father, Samuel, who in turn received them from a client in Helsinki, Finland.

We also know where these objects were created and why.

However, at this time we lack the information necessary to determine who specifically printed these bills, who distributed them, or even if, for that matter, they were distributed into circulation at all. How did these notes get out of the ghetto and when? How did something printed at the opening of the ghetto in 1940 survive the harsh conditions of the ghetto when so many of the people sent there did not? And how did these objects survive in such perfect condition?

Moreover, who was this mysterious client who paid Samuel Maslovat and how did they gain possession of these notes? There is much we do not know about these objects.

Unfortunately, like many such objects associated with the Holocaust, it seems likely that much of their story will likely never be known. However, what is known with some degree of certainty, is what will likely happen to these objects in the future. Julius has stressed that he feels no connection to these objects, relaying to us that he was, in effect, like his father before him, acting simply as their caretaker. These notes and coins have been held in stasis waiting for their story to be told; we have attempted to do that here to a varying degree of success. Preserved here in this digital exhibit, it is our hope that these objects can continue to act as an educational tool, and to act as an object of resistance against the policies and ideologues of the far right. One day in the future, pursuant to the wishes of Julius, it is likely that these objects will also be preserved in a formal museum or archival collection where they can act as a conduit to the past and inform the education of others in the future.

Additional Resources

-

"Currency Bills from The Terezin Ghetto" The National Library of Israel: http://web.nli.org.il/sites/

NLI/English/collections/ personalsites/Israel-Germany/ World-War-2/Pages/Ghetto- Banknotes.aspx -

"The Holocaust: Ghetto & Concentration Camp Money" by Marisa Natale, Jewish Virtual Library: https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ghetto-concentration-camp-money

-

"Paper Currency from the Łódź Ghetto" Montreal Holocaust Museum: https://

museeholocauste.ca/en/objects/ paper-currency-lodz-ghetto/ -

"The Bank for Purchase of Valuable Objects and Clothing Ciesielska Street (Bleicherweg)." Litzmannstadt Ghetto: http://www.lodz-ghetto.

com/the_bank_for_purchase_of_ valuable_objects_and_clothing. html,14

Project by Anthony Auchterlonie & Laura Bock, 2019