-

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook Frederick W. Langton’s scrapbook was created in the latter part of the nineteenth century, at a time when periodical publications were proliferating. Presented above are selected pages from Langton’s “Ruskiniana” scrapbook, a collection of documents taken from periodicals about the art critic John Ruskin.

One page from the album features two typed newspaper columns cut and pasted onto a brown piece of paper. The two columns are carefully placed side by side in the middle of the page, leaving a slight brown gap between them. The newspaper’s masthead is pasted at the top of the page, identifying the source of the typed columns as an issue of “The Graphic” from 30 March 1878. Another album page includes two pages of an article entitled “Art and Its Relation to Life” pasted side by side, with a line of the album’s brown paper separating the two densely printed sheets. A handwritten note pasted in just below these two pages slightly overlaps the article when it is unfolded for reading, as in the photograph included above. Printed text at the top of the note identifies it as a “Memorandum from George Allen, Sunnyside, Orpinton, Kent.” The memorandum is addressed by hand to “Rev. W. M. Richardson, Banbury” and dated 10 July 1877. The memorandum begins, “Dear Sir, In reply to your query about Professor Ruskin and his tea-shop, I beg to inform you that he did put an old servant into a shop… so that the poor in the neighbourhood round about might be able to get pure good tea and coffee.”

Another section of the scrapbook emphasizes the variety of materials included in the album: in addition to printed and hand-written materials, Langton included a full pamphlet, “Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics,” written by James McNeill Whistler and published on 24 December 1878.

-

Layette Pincushion

Layette Pincushion This layette pincushion is made of light-blue fabric, faded from the sun and mottled in places. A message pricked out in pins reading “God Bless Thee my baby” appears in cursive in the centre of the cushion. The first three words are capitalized and separated by pinheads. A curved frame of pinheads surrounds the message, and there are decorative details at the top, bottom, centre, and corners of the frame. The top decoration resembles a crown, and the bottom decoration either a teardrop or a leaf. The corners of the frame are marked with triangular shapes. To the left and right of the pinhead frame, there are curved floral designs of ribbon rosettes in pink, blue, yellow, and white, and leaves in soft green. White lace trims all four sides of the cushion, which measures five inches wide, three and three-quarters inches deep, and two inches high. The pincushion’s provenance is unknown, but it most likely formed part of a baby’s layette and seems to have been made by its mother, as suggested by the possessive “my” in the message.

-

Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin

Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin This page from J. Clifton Edgar’s “The Manikin in the Teaching of Practical Obstetrics,” published in “The New York Medical Journal” (December 1890), includes illustrations of a Budin-Pinard obstetric manikin, which was used to teach medical students. The illustrations are rendered in black and white and show the manikin with close attention to detail. The manikin represents the torso of a female body, from just above the breasts to a few inches above the knee. Crucial to the manikin’s function are its rubber vulva, anus, and inflated anterior abdominal wall. Whereas the manikin itself is made of wood and propped up with a small peg, the abdominal wall and genital area are made of rubber and appear to be attached to the base of the manikin with bands of adhesive material.

The article accompanying the illustration describes the manikin as follows: “the thighs are widely separated for convenience in operating, and the anterior abdominal wall is made of rubber capable of being distended with air, and so arranged on a frame hinged to the upper part of the body, that the whole may be thrown back, thus bringing the abdominal cavity and pelvic inlet into view. The pelvic excavation is so carved as to roughly represent the normal bony pelvis. And one piece of India rubber lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. And at the pelvic outlet is so moulded and secured to the margin of the inferior strait as to form the vulva, vagina, and perineum” (702).

-

Charlotte Brontë’s Dress

Charlotte Brontë’s Dress Charlotte Brontë wore this dress on her honeymoon to County Clare, Ireland. The dress consists of a bodice and a skirt, each made of lavender-coloured, striped, medium-weight silk. The bodice is adorned with tan-coloured silk velvet cuffs and collar, and edged with ten small triangles trimmed with silk fringe. The full-length skirt, attached to a waistband, is gathered across the centre back, while the skirt front is flat with small pleats at either side. A small bustle would have been worn underneath. Both the bodice and skirt are close fitting around the waist and fully lined with cream-coloured cotton. The bodice fastens down the centre front with fourteen metal hooks and eyes, and the skirt fastens with two large metal hooks and eyes on the right hand side.

The photos showing the interior of the dress reveal alterations and some of the damage to the interior caused by stress on the fabric.

-

Ella Kidman’s Autograph Album

Ella Kidman’s Autograph Album The first page, or “ownership page,” of Ella Kidman’s autograph album features its owner’s name prominently at the centre of its elaborate design. Kidman’s cursive handwriting is framed by a detailed ink drawing of an ocean scene: three seagulls coast above the water, drawing the viewer’s eye to the indication of clouds behind them and to a mountain range on the horizon. A cluster of jagged rocks juts out of the water below the seagulls; beyond this rock formation is a small sailboat. At the bottom left corner of the page are the words “from May. / Xmas 1897.” The album’s paper shows wear from the passage of time; it is wrinkled in places and fully torn at the bottom right corner.

Another page of Kidman’s album is decorated with layered rectangular shapes. Framed by these superimposed shapes are the signatures of Kidman’s friends and family. The uppermost rectangle features an illustration of a bundle of flowers lying horizontally on its side; opposite the flowers is a small illustration of a butterfly. In the shape below, two small winged insects decorate the top left corner of the rectangle.

A third page shows a skeleton-like shape running the length of the page. The design has been created with black ink and is almost perfectly symmetrical, bisecting the page down the middle. These distinctive shapes are called ink blot signatures or ghost signatures. To create an ink blog signature, album signers would fold the paper over their wet signatures and then re-open the page to reveal their unique ghostly signatures.

-

Miscarriage Specimens

Miscarriage Specimens A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints).

-

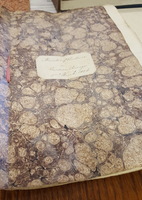

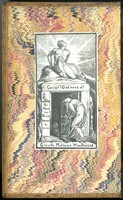

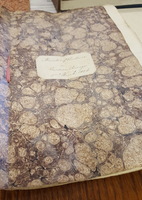

Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage

Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage Currently housed at the UK Parliamentary Archives, these handwritten manuscripts record the proceedings of the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords in London. With covers of hand-marbled paper, each booklet displays the date and the title of the case in the secretary’s handwriting on its cover. Each book contains a new day of proceedings, with each witness beginning on a new page. The paper is thick and textured, with the marbled covers taking on different dominant hues: green, red, or beige. The booklets are bound loosely with a red ribbon.

-

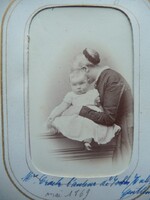

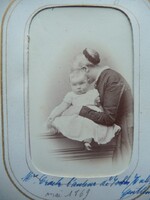

Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait

Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait In this black-and-white photograph, Dinah Craik embraces her sixteen-month-old adopted daughter, Dorothy. Craik stands beside her daughter, her left hand winding around her waist, while she bends to obscure her own face entirely behind Dorothy’s head. The photograph, which is housed in a private collection, is a portrait of Dorothy, whose gaze is directed at the viewer. Wearing mary jane-style shoes and a white-frilled dress that complements a similar white frill on her mother’s collar, Dorothy sits patiently with her arms relaxed at her sides. All that is visible of Craik herself are her hand, body, and ear, as well as her muted, conventional clothing and a dark band around her hair. Written across the bottom of the white and gold cardboard frame in blue ink are the words “Mrs. Craik l’auteur de John Halifax, Gentleman / mai 1869.”

-

George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude”

George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” The cover of George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” is a rich, brick-red colour, imprinted around the edge with an intricate border of repeating geometric shapes that surrounds an embossed stamp, perhaps that of the volume’s printer. Within the intricate border, the binding has a grainy appearance, while the rest of the surface appears smoother. The cover is slightly warped, and the edges look somewhat discoloured and bent, suggesting that the volume was well used.

Page 302 of the book features a header that identifies this page as a part of the “Conclusion” to “Book XIV” of “The Prelude.” Below this header are the last five printed lines of a poem and some handwritten text sketched in graphite pencil that reads:

Read second time (aloud to Polly)

at Niton, reclining on the cliff or in the

long grass, July 1867.

An earlier page from the volume includes more text at the top of the page, written in graphite pencil in a different hand. It reads:

Begun with J. at Wildbad in our walk

on a Sunday morning. July 1880.

Finished Aug. 23.

Below these handwritten lines are two lines of a poem with the title “Book First” and underneath, “Introduction – Childhood and School-time.”

The book is currently housed in the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

-

Tea Gown

Tea Gown The maker and place of origin of this tea gown are unknown but it was created from a European shawl, likely circa 1891. The gown is pictured at two angles on a white mannequin with a white paper headpiece; the back and front are showcased. Intricate vegetal and paisley patterns on different colour fields adorn the wool fabric. The gown is visually striking with a straight collar closed at the neck, a detachable shoulder cape trimmed in purple silk, fashionable full sleeves with cuffs, a fabric belt, and, over the belt in back, a series of box pleats from neck to floor called “Watteau pleats.” The collar, right hip pocket, and cuffs are cut from shawl sections with an olive field, while the belt and back bodice are cut from sections with a brighter shade of red than the rest of the gown, which is predominantly burgundy. The gown closes at centre front with mother-of-pearl buttons. The pleated back structure provides volume at the skirt but, unlike the eighteen-century style for which Watteau pleats are named, pleats are stitched down at the upper bodice to help delineate a corseted figure.

-

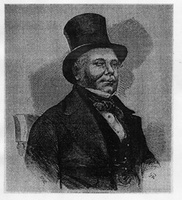

A Policeman's Hat

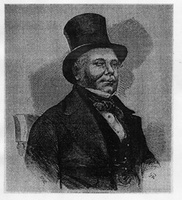

A Policeman's Hat This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material.

-

4 June Roundtable on Victorian Pregnancy & Childbirth

4 June Roundtable on Victorian Pregnancy & Childbirth This poster for our 4 June roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and is based on Gustave Léonard's de Jonghe's The Young Mother.

-

4 May Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture

4 May Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 4 May roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and based on the Ladies Carpet, which was the subject of Morna O'Neill's presentation.

-

9 March Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture

9 March Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 9 March roundtable was designed by Robert Steele, and based on a poster presented by Jordan Bear.

-

Amelia Wood's Conversation Tube & Pouch

Amelia Wood's Conversation Tube & Pouch This black conversation tube, now part of the Ken Seiling Waterloo Region Museum Collections, has a metal earpiece on one end of a long cotton tube and a metal mouthpiece on the other end. The black drawstring pouch that was used to store the conversation tube is decorated with ornate hand-beading, also in black: eyes, a nose, and the outlines of a face and feathers come together to form an owl’s face.

-

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset.

-

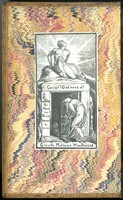

George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection"

George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection" These images come from a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s "Aids to Reflection" that belonged to Victorian author George MacDonald. One image shows the volume’s title page. This page is yellowed by time and contains a handwritten inscription in black ink in the top right corner to Louisa Powell, along with the date, “Nov. 5. 1847.” Below this inscription and the printed title is a sonnet written in the same script as the name and date. The first few letters of each line of the sonnet are obscured by the crease of the page. Other images show the black-and-white bookplate, bearing the name of “Greville Matheson MacDonald” and set against colourful marbled paper. The illustration on the bookplate depicts two figures, a muscular young man sitting atop a cavernous entryway shrouded in darkness, and another man, stooped with age, carrying a cane, and walking across the threshold of the same entrance. The darkness of the entryway contrasts with light emitting from the young man. The lintel of the cave bears the text “Corage! God mend al!” while the left post bears an image of a hand holding up a cross and the Latin text “per mare per terras domum tu erras” (“through sea and through land, you wander homeward”). At the bottom left-hand corner of the doorway is a Latin epsilon followed by the text “x Libris.” The book is currently held at the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University as part of their George MacDonald collection.

The inscription (as transcribed by Dr. Denae Dyck and Dr. Melinda Creech) reads as follows:

[?Whether] this day on earth shall often be,

[?I h]ave no wish that I can make for thee.

[?Nor] will I wish thee ever cloudless years.

[?Why] wish thee that which cannot be, I know

[?That] as the sun must shine, so clouds must grow.

[?And] as our being is, so are our tears:

[?And] one who hath given thanks for sorrow’s hour

[?May] never pray thou shouldst not know its power;

[?Ye]t there is one thing I can wish for thee –

[?That] the unbounded promise may be thine

[?When] all things in one Providence combine

[?So]rrows and joys in glorious unity –

[?But] bright or dark, unknown or understood,

[?All] things work together for thy good.

-

Hannah Claus's "interlacings"

Hannah Claus's "interlacings" “interlacings,” a looped projected animation, features a red-bordered octagon centred within a black space. Inside the border, concentric rings rotate in different directions, resembling a kaleidoscope as each ring slowly transforms from one pattern to another. The unmoving red octagon frames the animation with intricate Victorian designs accented with white and orange details. While some of the images included here and the video of the piece that is accessible online may look like a decontextualized digital mandala, the work originally existed as an installation. In the gallery, “interlacings” was projected onto the gallery floor and surrounded by a bed of pine needles that dried out over time, alluding to fading memories of the local landscape.

Initially, the projection looks uniformly Victorian, bringing to mind the types of designs popularized by William Morris, but as the inner rings shift and patterns morph out from the darkness, they highlight edible plants and flowers native to the Secwepemc territory (Kamloops, BC). For example, the outer ring spins rosehips, root vegetables, and raspberry bushes into bloom, while an inner ring includes roses and berries. These subtle transitions make it seem as though the piece itself is breathing, with greenery expanding out through an inhale and contracting in again through an exhale, but always remaining bound by the confines of the border.

-

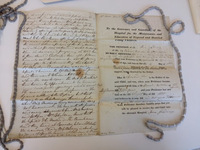

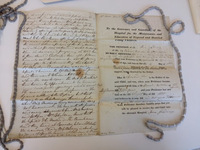

Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital

Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital This bundle of folded papers bound together by a white cloth ribbon records fascinating and moving stories: they are petitions completed by nineteenth-century women who applied to have their infants taken in by the London Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram (http://www.coram.org.uk).

One photograph included here shows the bundle of folded petitions, each petition containing other documents (including letters and reports) relating to an individual application. Additional images of a single, unfolded, sheet of paper filled with typed and written text present the petition of Ann Gidding, a mother who applied to the hospital in 1831. One of these images shows the back of the petition, which documents the outcome of Ann’s application (in this case a rejection as a bribe had been offered), as well as the report from the Hospital Inquirer, who was employed to uncover the character of the applicant. Another image shows the form that all applicants were required to complete, as well as the transcript of Ann’s oral testimony given in front of the all-male governing body as part of the application process. Like the Inquirer’s report, this testimony is reproduced in a mass of cursive penmanship that narrowly escapes spilling off the bottom of the page. Uniform creases produced by the petition’s mode of storage and staining of unknown origin are visible in the images.

-

The Brontë Family's Broken Hair Bracelet

The Brontë Family's Broken Hair Bracelet This simple but sophisticated nineteenth-century hairwork bracelet is composed of six thin plaits of light brown hair, joined together at each end by metal clasps. The photographs above show the bracelet, housed at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, in its current state. Uniformly muted in colour but slightly iridescent, the golden tinge of the hair complements the glinting metal in the flat links of the clasp. A partially obscured safety chain connects the two clasps at the ends of the bracelet, hidden underneath the body of the piece. The bracelet features two kinds of braid, alternating between the two styles to achieve an illusion of complexity and intricacy when viewed from afar. There is, however, one broken plait that has detached from the rest; having become partially unraveled, these hairs splay out loosely in all directions. The hair at the end of the broken plait still holds an imprint of its previous braided configuration, a subtle imprint that persists despite the passage of time.

-

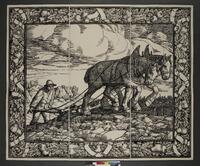

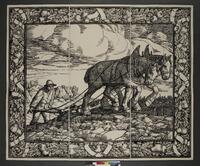

William Strang's "The Plough"

William Strang's "The Plough" “The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture.

-

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf"

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf" Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration.

-

Mrs. Alexander's Mark

Mrs. Alexander's Mark This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page.

The body text of the page reads:

labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys:

“Though my lot be hard and lonely,

Yet I hope – I hope through all.”

The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library.

-

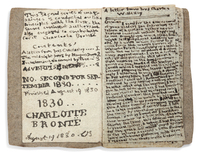

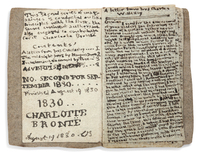

Charlotte Brontё’s “Little Book”

Charlotte Brontё’s “Little Book” This “little book” by Charlotte Brontë contains an edition of "The Young Men’s Magazine," created in 1813 when Charlotte was just 14 years old. The size of a matchbox, the book features neat but cramped handwriting in black ink. The left-hand side of the left page lists the book’s contents with titles and corresponding page numbers. Below the contents, the year 1830 and the author’s name in all capital letters appear prominently across the bottom third of the page. The date of August 19 1830 runs across the bottom of the page followed by the initials CB. The right page has a title that corresponds to the first entry in the table of contents on the facing page and is filled with small, indeed barely legible, text.

-

J. M. Whistler's "The Fleet: Monitors"

J. M. Whistler's "The Fleet: Monitors" “The Fleet: Monitors” from James McNeill Whistler’s “Jubilee Set” portrays the naval review of Queen Victoria’s 1887 Jubilee and five onlookers. The etching, completed in black ink on laid ivory paper, uses broken lines to outline an array of steam-powered ships with tall masts in the background. Additional ships are depicted with less detail on the left-hand side. Minimal linework suggests the forms of a few clouds in the sky as well as waves in the river. Four men and one woman stand in the left foreground and they all lack facial detail. The woman wears a sunhat and is looking towards the naval display. The first man from the left wears a hat and has a moustache; the second wears a hat and is reading a book; the third and fourth are also wearing hats and are drawn with the least amount of detail. All four men face the foreground, looking away from the ships that make up the background of the etching. The etching as a whole is dominated by negative space, punctuated by thin, spare lines. The paper is textured, and the print featured here, from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, has slight discolouration around the edges. Some unevenness in the print tone is evident on the left side of the etching. Relatively small, the print is 14.3 by 22.1 centimetres, or 5.6 by 8.7 inches.

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook Frederick W. Langton’s scrapbook was created in the latter part of the nineteenth century, at a time when periodical publications were proliferating. Presented above are selected pages from Langton’s “Ruskiniana” scrapbook, a collection of documents taken from periodicals about the art critic John Ruskin. One page from the album features two typed newspaper columns cut and pasted onto a brown piece of paper. The two columns are carefully placed side by side in the middle of the page, leaving a slight brown gap between them. The newspaper’s masthead is pasted at the top of the page, identifying the source of the typed columns as an issue of “The Graphic” from 30 March 1878. Another album page includes two pages of an article entitled “Art and Its Relation to Life” pasted side by side, with a line of the album’s brown paper separating the two densely printed sheets. A handwritten note pasted in just below these two pages slightly overlaps the article when it is unfolded for reading, as in the photograph included above. Printed text at the top of the note identifies it as a “Memorandum from George Allen, Sunnyside, Orpinton, Kent.” The memorandum is addressed by hand to “Rev. W. M. Richardson, Banbury” and dated 10 July 1877. The memorandum begins, “Dear Sir, In reply to your query about Professor Ruskin and his tea-shop, I beg to inform you that he did put an old servant into a shop… so that the poor in the neighbourhood round about might be able to get pure good tea and coffee.” Another section of the scrapbook emphasizes the variety of materials included in the album: in addition to printed and hand-written materials, Langton included a full pamphlet, “Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics,” written by James McNeill Whistler and published on 24 December 1878.

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook Frederick W. Langton’s scrapbook was created in the latter part of the nineteenth century, at a time when periodical publications were proliferating. Presented above are selected pages from Langton’s “Ruskiniana” scrapbook, a collection of documents taken from periodicals about the art critic John Ruskin. One page from the album features two typed newspaper columns cut and pasted onto a brown piece of paper. The two columns are carefully placed side by side in the middle of the page, leaving a slight brown gap between them. The newspaper’s masthead is pasted at the top of the page, identifying the source of the typed columns as an issue of “The Graphic” from 30 March 1878. Another album page includes two pages of an article entitled “Art and Its Relation to Life” pasted side by side, with a line of the album’s brown paper separating the two densely printed sheets. A handwritten note pasted in just below these two pages slightly overlaps the article when it is unfolded for reading, as in the photograph included above. Printed text at the top of the note identifies it as a “Memorandum from George Allen, Sunnyside, Orpinton, Kent.” The memorandum is addressed by hand to “Rev. W. M. Richardson, Banbury” and dated 10 July 1877. The memorandum begins, “Dear Sir, In reply to your query about Professor Ruskin and his tea-shop, I beg to inform you that he did put an old servant into a shop… so that the poor in the neighbourhood round about might be able to get pure good tea and coffee.” Another section of the scrapbook emphasizes the variety of materials included in the album: in addition to printed and hand-written materials, Langton included a full pamphlet, “Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics,” written by James McNeill Whistler and published on 24 December 1878. Layette Pincushion This layette pincushion is made of light-blue fabric, faded from the sun and mottled in places. A message pricked out in pins reading “God Bless Thee my baby” appears in cursive in the centre of the cushion. The first three words are capitalized and separated by pinheads. A curved frame of pinheads surrounds the message, and there are decorative details at the top, bottom, centre, and corners of the frame. The top decoration resembles a crown, and the bottom decoration either a teardrop or a leaf. The corners of the frame are marked with triangular shapes. To the left and right of the pinhead frame, there are curved floral designs of ribbon rosettes in pink, blue, yellow, and white, and leaves in soft green. White lace trims all four sides of the cushion, which measures five inches wide, three and three-quarters inches deep, and two inches high. The pincushion’s provenance is unknown, but it most likely formed part of a baby’s layette and seems to have been made by its mother, as suggested by the possessive “my” in the message.

Layette Pincushion This layette pincushion is made of light-blue fabric, faded from the sun and mottled in places. A message pricked out in pins reading “God Bless Thee my baby” appears in cursive in the centre of the cushion. The first three words are capitalized and separated by pinheads. A curved frame of pinheads surrounds the message, and there are decorative details at the top, bottom, centre, and corners of the frame. The top decoration resembles a crown, and the bottom decoration either a teardrop or a leaf. The corners of the frame are marked with triangular shapes. To the left and right of the pinhead frame, there are curved floral designs of ribbon rosettes in pink, blue, yellow, and white, and leaves in soft green. White lace trims all four sides of the cushion, which measures five inches wide, three and three-quarters inches deep, and two inches high. The pincushion’s provenance is unknown, but it most likely formed part of a baby’s layette and seems to have been made by its mother, as suggested by the possessive “my” in the message. Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin This page from J. Clifton Edgar’s “The Manikin in the Teaching of Practical Obstetrics,” published in “The New York Medical Journal” (December 1890), includes illustrations of a Budin-Pinard obstetric manikin, which was used to teach medical students. The illustrations are rendered in black and white and show the manikin with close attention to detail. The manikin represents the torso of a female body, from just above the breasts to a few inches above the knee. Crucial to the manikin’s function are its rubber vulva, anus, and inflated anterior abdominal wall. Whereas the manikin itself is made of wood and propped up with a small peg, the abdominal wall and genital area are made of rubber and appear to be attached to the base of the manikin with bands of adhesive material. The article accompanying the illustration describes the manikin as follows: “the thighs are widely separated for convenience in operating, and the anterior abdominal wall is made of rubber capable of being distended with air, and so arranged on a frame hinged to the upper part of the body, that the whole may be thrown back, thus bringing the abdominal cavity and pelvic inlet into view. The pelvic excavation is so carved as to roughly represent the normal bony pelvis. And one piece of India rubber lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. And at the pelvic outlet is so moulded and secured to the margin of the inferior strait as to form the vulva, vagina, and perineum” (702).

Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin This page from J. Clifton Edgar’s “The Manikin in the Teaching of Practical Obstetrics,” published in “The New York Medical Journal” (December 1890), includes illustrations of a Budin-Pinard obstetric manikin, which was used to teach medical students. The illustrations are rendered in black and white and show the manikin with close attention to detail. The manikin represents the torso of a female body, from just above the breasts to a few inches above the knee. Crucial to the manikin’s function are its rubber vulva, anus, and inflated anterior abdominal wall. Whereas the manikin itself is made of wood and propped up with a small peg, the abdominal wall and genital area are made of rubber and appear to be attached to the base of the manikin with bands of adhesive material. The article accompanying the illustration describes the manikin as follows: “the thighs are widely separated for convenience in operating, and the anterior abdominal wall is made of rubber capable of being distended with air, and so arranged on a frame hinged to the upper part of the body, that the whole may be thrown back, thus bringing the abdominal cavity and pelvic inlet into view. The pelvic excavation is so carved as to roughly represent the normal bony pelvis. And one piece of India rubber lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. And at the pelvic outlet is so moulded and secured to the margin of the inferior strait as to form the vulva, vagina, and perineum” (702). Charlotte Brontë’s Dress Charlotte Brontë wore this dress on her honeymoon to County Clare, Ireland. The dress consists of a bodice and a skirt, each made of lavender-coloured, striped, medium-weight silk. The bodice is adorned with tan-coloured silk velvet cuffs and collar, and edged with ten small triangles trimmed with silk fringe. The full-length skirt, attached to a waistband, is gathered across the centre back, while the skirt front is flat with small pleats at either side. A small bustle would have been worn underneath. Both the bodice and skirt are close fitting around the waist and fully lined with cream-coloured cotton. The bodice fastens down the centre front with fourteen metal hooks and eyes, and the skirt fastens with two large metal hooks and eyes on the right hand side. The photos showing the interior of the dress reveal alterations and some of the damage to the interior caused by stress on the fabric.

Charlotte Brontë’s Dress Charlotte Brontë wore this dress on her honeymoon to County Clare, Ireland. The dress consists of a bodice and a skirt, each made of lavender-coloured, striped, medium-weight silk. The bodice is adorned with tan-coloured silk velvet cuffs and collar, and edged with ten small triangles trimmed with silk fringe. The full-length skirt, attached to a waistband, is gathered across the centre back, while the skirt front is flat with small pleats at either side. A small bustle would have been worn underneath. Both the bodice and skirt are close fitting around the waist and fully lined with cream-coloured cotton. The bodice fastens down the centre front with fourteen metal hooks and eyes, and the skirt fastens with two large metal hooks and eyes on the right hand side. The photos showing the interior of the dress reveal alterations and some of the damage to the interior caused by stress on the fabric. Ella Kidman’s Autograph Album The first page, or “ownership page,” of Ella Kidman’s autograph album features its owner’s name prominently at the centre of its elaborate design. Kidman’s cursive handwriting is framed by a detailed ink drawing of an ocean scene: three seagulls coast above the water, drawing the viewer’s eye to the indication of clouds behind them and to a mountain range on the horizon. A cluster of jagged rocks juts out of the water below the seagulls; beyond this rock formation is a small sailboat. At the bottom left corner of the page are the words “from May. / Xmas 1897.” The album’s paper shows wear from the passage of time; it is wrinkled in places and fully torn at the bottom right corner. Another page of Kidman’s album is decorated with layered rectangular shapes. Framed by these superimposed shapes are the signatures of Kidman’s friends and family. The uppermost rectangle features an illustration of a bundle of flowers lying horizontally on its side; opposite the flowers is a small illustration of a butterfly. In the shape below, two small winged insects decorate the top left corner of the rectangle. A third page shows a skeleton-like shape running the length of the page. The design has been created with black ink and is almost perfectly symmetrical, bisecting the page down the middle. These distinctive shapes are called ink blot signatures or ghost signatures. To create an ink blog signature, album signers would fold the paper over their wet signatures and then re-open the page to reveal their unique ghostly signatures.

Ella Kidman’s Autograph Album The first page, or “ownership page,” of Ella Kidman’s autograph album features its owner’s name prominently at the centre of its elaborate design. Kidman’s cursive handwriting is framed by a detailed ink drawing of an ocean scene: three seagulls coast above the water, drawing the viewer’s eye to the indication of clouds behind them and to a mountain range on the horizon. A cluster of jagged rocks juts out of the water below the seagulls; beyond this rock formation is a small sailboat. At the bottom left corner of the page are the words “from May. / Xmas 1897.” The album’s paper shows wear from the passage of time; it is wrinkled in places and fully torn at the bottom right corner. Another page of Kidman’s album is decorated with layered rectangular shapes. Framed by these superimposed shapes are the signatures of Kidman’s friends and family. The uppermost rectangle features an illustration of a bundle of flowers lying horizontally on its side; opposite the flowers is a small illustration of a butterfly. In the shape below, two small winged insects decorate the top left corner of the rectangle. A third page shows a skeleton-like shape running the length of the page. The design has been created with black ink and is almost perfectly symmetrical, bisecting the page down the middle. These distinctive shapes are called ink blot signatures or ghost signatures. To create an ink blog signature, album signers would fold the paper over their wet signatures and then re-open the page to reveal their unique ghostly signatures. Miscarriage Specimens A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints).

Miscarriage Specimens A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints). Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage Currently housed at the UK Parliamentary Archives, these handwritten manuscripts record the proceedings of the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords in London. With covers of hand-marbled paper, each booklet displays the date and the title of the case in the secretary’s handwriting on its cover. Each book contains a new day of proceedings, with each witness beginning on a new page. The paper is thick and textured, with the marbled covers taking on different dominant hues: green, red, or beige. The booklets are bound loosely with a red ribbon.

Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage Currently housed at the UK Parliamentary Archives, these handwritten manuscripts record the proceedings of the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords in London. With covers of hand-marbled paper, each booklet displays the date and the title of the case in the secretary’s handwriting on its cover. Each book contains a new day of proceedings, with each witness beginning on a new page. The paper is thick and textured, with the marbled covers taking on different dominant hues: green, red, or beige. The booklets are bound loosely with a red ribbon. Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait In this black-and-white photograph, Dinah Craik embraces her sixteen-month-old adopted daughter, Dorothy. Craik stands beside her daughter, her left hand winding around her waist, while she bends to obscure her own face entirely behind Dorothy’s head. The photograph, which is housed in a private collection, is a portrait of Dorothy, whose gaze is directed at the viewer. Wearing mary jane-style shoes and a white-frilled dress that complements a similar white frill on her mother’s collar, Dorothy sits patiently with her arms relaxed at her sides. All that is visible of Craik herself are her hand, body, and ear, as well as her muted, conventional clothing and a dark band around her hair. Written across the bottom of the white and gold cardboard frame in blue ink are the words “Mrs. Craik l’auteur de John Halifax, Gentleman / mai 1869.”

Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait In this black-and-white photograph, Dinah Craik embraces her sixteen-month-old adopted daughter, Dorothy. Craik stands beside her daughter, her left hand winding around her waist, while she bends to obscure her own face entirely behind Dorothy’s head. The photograph, which is housed in a private collection, is a portrait of Dorothy, whose gaze is directed at the viewer. Wearing mary jane-style shoes and a white-frilled dress that complements a similar white frill on her mother’s collar, Dorothy sits patiently with her arms relaxed at her sides. All that is visible of Craik herself are her hand, body, and ear, as well as her muted, conventional clothing and a dark band around her hair. Written across the bottom of the white and gold cardboard frame in blue ink are the words “Mrs. Craik l’auteur de John Halifax, Gentleman / mai 1869.” George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” The cover of George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” is a rich, brick-red colour, imprinted around the edge with an intricate border of repeating geometric shapes that surrounds an embossed stamp, perhaps that of the volume’s printer. Within the intricate border, the binding has a grainy appearance, while the rest of the surface appears smoother. The cover is slightly warped, and the edges look somewhat discoloured and bent, suggesting that the volume was well used. Page 302 of the book features a header that identifies this page as a part of the “Conclusion” to “Book XIV” of “The Prelude.” Below this header are the last five printed lines of a poem and some handwritten text sketched in graphite pencil that reads: Read second time (aloud to Polly) at Niton, reclining on the cliff or in the long grass, July 1867. An earlier page from the volume includes more text at the top of the page, written in graphite pencil in a different hand. It reads: Begun with J. at Wildbad in our walk on a Sunday morning. July 1880. Finished Aug. 23. Below these handwritten lines are two lines of a poem with the title “Book First” and underneath, “Introduction – Childhood and School-time.” The book is currently housed in the Beinecke Library at Yale University.

George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” The cover of George Eliot’s copy of Wordsworth’s “The Prelude” is a rich, brick-red colour, imprinted around the edge with an intricate border of repeating geometric shapes that surrounds an embossed stamp, perhaps that of the volume’s printer. Within the intricate border, the binding has a grainy appearance, while the rest of the surface appears smoother. The cover is slightly warped, and the edges look somewhat discoloured and bent, suggesting that the volume was well used. Page 302 of the book features a header that identifies this page as a part of the “Conclusion” to “Book XIV” of “The Prelude.” Below this header are the last five printed lines of a poem and some handwritten text sketched in graphite pencil that reads: Read second time (aloud to Polly) at Niton, reclining on the cliff or in the long grass, July 1867. An earlier page from the volume includes more text at the top of the page, written in graphite pencil in a different hand. It reads: Begun with J. at Wildbad in our walk on a Sunday morning. July 1880. Finished Aug. 23. Below these handwritten lines are two lines of a poem with the title “Book First” and underneath, “Introduction – Childhood and School-time.” The book is currently housed in the Beinecke Library at Yale University. Tea Gown The maker and place of origin of this tea gown are unknown but it was created from a European shawl, likely circa 1891. The gown is pictured at two angles on a white mannequin with a white paper headpiece; the back and front are showcased. Intricate vegetal and paisley patterns on different colour fields adorn the wool fabric. The gown is visually striking with a straight collar closed at the neck, a detachable shoulder cape trimmed in purple silk, fashionable full sleeves with cuffs, a fabric belt, and, over the belt in back, a series of box pleats from neck to floor called “Watteau pleats.” The collar, right hip pocket, and cuffs are cut from shawl sections with an olive field, while the belt and back bodice are cut from sections with a brighter shade of red than the rest of the gown, which is predominantly burgundy. The gown closes at centre front with mother-of-pearl buttons. The pleated back structure provides volume at the skirt but, unlike the eighteen-century style for which Watteau pleats are named, pleats are stitched down at the upper bodice to help delineate a corseted figure.

Tea Gown The maker and place of origin of this tea gown are unknown but it was created from a European shawl, likely circa 1891. The gown is pictured at two angles on a white mannequin with a white paper headpiece; the back and front are showcased. Intricate vegetal and paisley patterns on different colour fields adorn the wool fabric. The gown is visually striking with a straight collar closed at the neck, a detachable shoulder cape trimmed in purple silk, fashionable full sleeves with cuffs, a fabric belt, and, over the belt in back, a series of box pleats from neck to floor called “Watteau pleats.” The collar, right hip pocket, and cuffs are cut from shawl sections with an olive field, while the belt and back bodice are cut from sections with a brighter shade of red than the rest of the gown, which is predominantly burgundy. The gown closes at centre front with mother-of-pearl buttons. The pleated back structure provides volume at the skirt but, unlike the eighteen-century style for which Watteau pleats are named, pleats are stitched down at the upper bodice to help delineate a corseted figure. A Policeman's Hat This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material.

A Policeman's Hat This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material. 4 June Roundtable on Victorian Pregnancy & Childbirth This poster for our 4 June roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and is based on Gustave Léonard's de Jonghe's The Young Mother.

4 June Roundtable on Victorian Pregnancy & Childbirth This poster for our 4 June roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and is based on Gustave Léonard's de Jonghe's The Young Mother. 4 May Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 4 May roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and based on the Ladies Carpet, which was the subject of Morna O'Neill's presentation.

4 May Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 4 May roundtable was designed by Robert Steele and based on the Ladies Carpet, which was the subject of Morna O'Neill's presentation. 9 March Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 9 March roundtable was designed by Robert Steele, and based on a poster presented by Jordan Bear.

9 March Roundtable on Victorian Material Culture This poster for our 9 March roundtable was designed by Robert Steele, and based on a poster presented by Jordan Bear. Amelia Wood's Conversation Tube & Pouch This black conversation tube, now part of the Ken Seiling Waterloo Region Museum Collections, has a metal earpiece on one end of a long cotton tube and a metal mouthpiece on the other end. The black drawstring pouch that was used to store the conversation tube is decorated with ornate hand-beading, also in black: eyes, a nose, and the outlines of a face and feathers come together to form an owl’s face.

Amelia Wood's Conversation Tube & Pouch This black conversation tube, now part of the Ken Seiling Waterloo Region Museum Collections, has a metal earpiece on one end of a long cotton tube and a metal mouthpiece on the other end. The black drawstring pouch that was used to store the conversation tube is decorated with ornate hand-beading, also in black: eyes, a nose, and the outlines of a face and feathers come together to form an owl’s face. William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset.

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset. George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection" These images come from a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s "Aids to Reflection" that belonged to Victorian author George MacDonald. One image shows the volume’s title page. This page is yellowed by time and contains a handwritten inscription in black ink in the top right corner to Louisa Powell, along with the date, “Nov. 5. 1847.” Below this inscription and the printed title is a sonnet written in the same script as the name and date. The first few letters of each line of the sonnet are obscured by the crease of the page. Other images show the black-and-white bookplate, bearing the name of “Greville Matheson MacDonald” and set against colourful marbled paper. The illustration on the bookplate depicts two figures, a muscular young man sitting atop a cavernous entryway shrouded in darkness, and another man, stooped with age, carrying a cane, and walking across the threshold of the same entrance. The darkness of the entryway contrasts with light emitting from the young man. The lintel of the cave bears the text “Corage! God mend al!” while the left post bears an image of a hand holding up a cross and the Latin text “per mare per terras domum tu erras” (“through sea and through land, you wander homeward”). At the bottom left-hand corner of the doorway is a Latin epsilon followed by the text “x Libris.” The book is currently held at the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University as part of their George MacDonald collection. The inscription (as transcribed by Dr. Denae Dyck and Dr. Melinda Creech) reads as follows: [?Whether] this day on earth shall often be, [?I h]ave no wish that I can make for thee. [?Nor] will I wish thee ever cloudless years. [?Why] wish thee that which cannot be, I know [?That] as the sun must shine, so clouds must grow. [?And] as our being is, so are our tears: [?And] one who hath given thanks for sorrow’s hour [?May] never pray thou shouldst not know its power; [?Ye]t there is one thing I can wish for thee – [?That] the unbounded promise may be thine [?When] all things in one Providence combine [?So]rrows and joys in glorious unity – [?But] bright or dark, unknown or understood, [?All] things work together for thy good.

George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection" These images come from a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s "Aids to Reflection" that belonged to Victorian author George MacDonald. One image shows the volume’s title page. This page is yellowed by time and contains a handwritten inscription in black ink in the top right corner to Louisa Powell, along with the date, “Nov. 5. 1847.” Below this inscription and the printed title is a sonnet written in the same script as the name and date. The first few letters of each line of the sonnet are obscured by the crease of the page. Other images show the black-and-white bookplate, bearing the name of “Greville Matheson MacDonald” and set against colourful marbled paper. The illustration on the bookplate depicts two figures, a muscular young man sitting atop a cavernous entryway shrouded in darkness, and another man, stooped with age, carrying a cane, and walking across the threshold of the same entrance. The darkness of the entryway contrasts with light emitting from the young man. The lintel of the cave bears the text “Corage! God mend al!” while the left post bears an image of a hand holding up a cross and the Latin text “per mare per terras domum tu erras” (“through sea and through land, you wander homeward”). At the bottom left-hand corner of the doorway is a Latin epsilon followed by the text “x Libris.” The book is currently held at the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University as part of their George MacDonald collection. The inscription (as transcribed by Dr. Denae Dyck and Dr. Melinda Creech) reads as follows: [?Whether] this day on earth shall often be, [?I h]ave no wish that I can make for thee. [?Nor] will I wish thee ever cloudless years. [?Why] wish thee that which cannot be, I know [?That] as the sun must shine, so clouds must grow. [?And] as our being is, so are our tears: [?And] one who hath given thanks for sorrow’s hour [?May] never pray thou shouldst not know its power; [?Ye]t there is one thing I can wish for thee – [?That] the unbounded promise may be thine [?When] all things in one Providence combine [?So]rrows and joys in glorious unity – [?But] bright or dark, unknown or understood, [?All] things work together for thy good. Hannah Claus's "interlacings" “interlacings,” a looped projected animation, features a red-bordered octagon centred within a black space. Inside the border, concentric rings rotate in different directions, resembling a kaleidoscope as each ring slowly transforms from one pattern to another. The unmoving red octagon frames the animation with intricate Victorian designs accented with white and orange details. While some of the images included here and the video of the piece that is accessible online may look like a decontextualized digital mandala, the work originally existed as an installation. In the gallery, “interlacings” was projected onto the gallery floor and surrounded by a bed of pine needles that dried out over time, alluding to fading memories of the local landscape. Initially, the projection looks uniformly Victorian, bringing to mind the types of designs popularized by William Morris, but as the inner rings shift and patterns morph out from the darkness, they highlight edible plants and flowers native to the Secwepemc territory (Kamloops, BC). For example, the outer ring spins rosehips, root vegetables, and raspberry bushes into bloom, while an inner ring includes roses and berries. These subtle transitions make it seem as though the piece itself is breathing, with greenery expanding out through an inhale and contracting in again through an exhale, but always remaining bound by the confines of the border.

Hannah Claus's "interlacings" “interlacings,” a looped projected animation, features a red-bordered octagon centred within a black space. Inside the border, concentric rings rotate in different directions, resembling a kaleidoscope as each ring slowly transforms from one pattern to another. The unmoving red octagon frames the animation with intricate Victorian designs accented with white and orange details. While some of the images included here and the video of the piece that is accessible online may look like a decontextualized digital mandala, the work originally existed as an installation. In the gallery, “interlacings” was projected onto the gallery floor and surrounded by a bed of pine needles that dried out over time, alluding to fading memories of the local landscape. Initially, the projection looks uniformly Victorian, bringing to mind the types of designs popularized by William Morris, but as the inner rings shift and patterns morph out from the darkness, they highlight edible plants and flowers native to the Secwepemc territory (Kamloops, BC). For example, the outer ring spins rosehips, root vegetables, and raspberry bushes into bloom, while an inner ring includes roses and berries. These subtle transitions make it seem as though the piece itself is breathing, with greenery expanding out through an inhale and contracting in again through an exhale, but always remaining bound by the confines of the border. Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital This bundle of folded papers bound together by a white cloth ribbon records fascinating and moving stories: they are petitions completed by nineteenth-century women who applied to have their infants taken in by the London Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram (http://www.coram.org.uk). One photograph included here shows the bundle of folded petitions, each petition containing other documents (including letters and reports) relating to an individual application. Additional images of a single, unfolded, sheet of paper filled with typed and written text present the petition of Ann Gidding, a mother who applied to the hospital in 1831. One of these images shows the back of the petition, which documents the outcome of Ann’s application (in this case a rejection as a bribe had been offered), as well as the report from the Hospital Inquirer, who was employed to uncover the character of the applicant. Another image shows the form that all applicants were required to complete, as well as the transcript of Ann’s oral testimony given in front of the all-male governing body as part of the application process. Like the Inquirer’s report, this testimony is reproduced in a mass of cursive penmanship that narrowly escapes spilling off the bottom of the page. Uniform creases produced by the petition’s mode of storage and staining of unknown origin are visible in the images.

Mother's Petition to the Foundling Hospital This bundle of folded papers bound together by a white cloth ribbon records fascinating and moving stories: they are petitions completed by nineteenth-century women who applied to have their infants taken in by the London Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram (http://www.coram.org.uk). One photograph included here shows the bundle of folded petitions, each petition containing other documents (including letters and reports) relating to an individual application. Additional images of a single, unfolded, sheet of paper filled with typed and written text present the petition of Ann Gidding, a mother who applied to the hospital in 1831. One of these images shows the back of the petition, which documents the outcome of Ann’s application (in this case a rejection as a bribe had been offered), as well as the report from the Hospital Inquirer, who was employed to uncover the character of the applicant. Another image shows the form that all applicants were required to complete, as well as the transcript of Ann’s oral testimony given in front of the all-male governing body as part of the application process. Like the Inquirer’s report, this testimony is reproduced in a mass of cursive penmanship that narrowly escapes spilling off the bottom of the page. Uniform creases produced by the petition’s mode of storage and staining of unknown origin are visible in the images. The Brontë Family's Broken Hair Bracelet This simple but sophisticated nineteenth-century hairwork bracelet is composed of six thin plaits of light brown hair, joined together at each end by metal clasps. The photographs above show the bracelet, housed at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, in its current state. Uniformly muted in colour but slightly iridescent, the golden tinge of the hair complements the glinting metal in the flat links of the clasp. A partially obscured safety chain connects the two clasps at the ends of the bracelet, hidden underneath the body of the piece. The bracelet features two kinds of braid, alternating between the two styles to achieve an illusion of complexity and intricacy when viewed from afar. There is, however, one broken plait that has detached from the rest; having become partially unraveled, these hairs splay out loosely in all directions. The hair at the end of the broken plait still holds an imprint of its previous braided configuration, a subtle imprint that persists despite the passage of time.

The Brontë Family's Broken Hair Bracelet This simple but sophisticated nineteenth-century hairwork bracelet is composed of six thin plaits of light brown hair, joined together at each end by metal clasps. The photographs above show the bracelet, housed at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, in its current state. Uniformly muted in colour but slightly iridescent, the golden tinge of the hair complements the glinting metal in the flat links of the clasp. A partially obscured safety chain connects the two clasps at the ends of the bracelet, hidden underneath the body of the piece. The bracelet features two kinds of braid, alternating between the two styles to achieve an illusion of complexity and intricacy when viewed from afar. There is, however, one broken plait that has detached from the rest; having become partially unraveled, these hairs splay out loosely in all directions. The hair at the end of the broken plait still holds an imprint of its previous braided configuration, a subtle imprint that persists despite the passage of time. William Strang's "The Plough" “The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture.

William Strang's "The Plough" “The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture. Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf" Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration.

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf" Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration. Mrs. Alexander's Mark This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page. The body text of the page reads: labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys: “Though my lot be hard and lonely, Yet I hope – I hope through all.” The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library.

Mrs. Alexander's Mark This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page. The body text of the page reads: labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys: “Though my lot be hard and lonely, Yet I hope – I hope through all.” The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library. Charlotte Brontё’s “Little Book” This “little book” by Charlotte Brontë contains an edition of "The Young Men’s Magazine," created in 1813 when Charlotte was just 14 years old. The size of a matchbox, the book features neat but cramped handwriting in black ink. The left-hand side of the left page lists the book’s contents with titles and corresponding page numbers. Below the contents, the year 1830 and the author’s name in all capital letters appear prominently across the bottom third of the page. The date of August 19 1830 runs across the bottom of the page followed by the initials CB. The right page has a title that corresponds to the first entry in the table of contents on the facing page and is filled with small, indeed barely legible, text.