Items

Subject is exactly

print

-

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook Frederick W. Langton’s scrapbook was created in the latter part of the nineteenth century, at a time when periodical publications were proliferating. Presented above are selected pages from Langton’s “Ruskiniana” scrapbook, a collection of documents taken from periodicals about the art critic John Ruskin. One page from the album features two typed newspaper columns cut and pasted onto a brown piece of paper. The two columns are carefully placed side by side in the middle of the page, leaving a slight brown gap between them. The newspaper’s masthead is pasted at the top of the page, identifying the source of the typed columns as an issue of “The Graphic” from 30 March 1878. Another album page includes two pages of an article entitled “Art and Its Relation to Life” pasted side by side, with a line of the album’s brown paper separating the two densely printed sheets. A handwritten note pasted in just below these two pages slightly overlaps the article when it is unfolded for reading, as in the photograph included above. Printed text at the top of the note identifies it as a “Memorandum from George Allen, Sunnyside, Orpinton, Kent.” The memorandum is addressed by hand to “Rev. W. M. Richardson, Banbury” and dated 10 July 1877. The memorandum begins, “Dear Sir, In reply to your query about Professor Ruskin and his tea-shop, I beg to inform you that he did put an old servant into a shop… so that the poor in the neighbourhood round about might be able to get pure good tea and coffee.” Another section of the scrapbook emphasizes the variety of materials included in the album: in addition to printed and hand-written materials, Langton included a full pamphlet, “Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics,” written by James McNeill Whistler and published on 24 December 1878.

Frederick Langton’s Scrapbook Frederick W. Langton’s scrapbook was created in the latter part of the nineteenth century, at a time when periodical publications were proliferating. Presented above are selected pages from Langton’s “Ruskiniana” scrapbook, a collection of documents taken from periodicals about the art critic John Ruskin. One page from the album features two typed newspaper columns cut and pasted onto a brown piece of paper. The two columns are carefully placed side by side in the middle of the page, leaving a slight brown gap between them. The newspaper’s masthead is pasted at the top of the page, identifying the source of the typed columns as an issue of “The Graphic” from 30 March 1878. Another album page includes two pages of an article entitled “Art and Its Relation to Life” pasted side by side, with a line of the album’s brown paper separating the two densely printed sheets. A handwritten note pasted in just below these two pages slightly overlaps the article when it is unfolded for reading, as in the photograph included above. Printed text at the top of the note identifies it as a “Memorandum from George Allen, Sunnyside, Orpinton, Kent.” The memorandum is addressed by hand to “Rev. W. M. Richardson, Banbury” and dated 10 July 1877. The memorandum begins, “Dear Sir, In reply to your query about Professor Ruskin and his tea-shop, I beg to inform you that he did put an old servant into a shop… so that the poor in the neighbourhood round about might be able to get pure good tea and coffee.” Another section of the scrapbook emphasizes the variety of materials included in the album: in addition to printed and hand-written materials, Langton included a full pamphlet, “Whistler v. Ruskin: Art & Art Critics,” written by James McNeill Whistler and published on 24 December 1878. -

Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin This page from J. Clifton Edgar’s “The Manikin in the Teaching of Practical Obstetrics,” published in “The New York Medical Journal” (December 1890), includes illustrations of a Budin-Pinard obstetric manikin, which was used to teach medical students. The illustrations are rendered in black and white and show the manikin with close attention to detail. The manikin represents the torso of a female body, from just above the breasts to a few inches above the knee. Crucial to the manikin’s function are its rubber vulva, anus, and inflated anterior abdominal wall. Whereas the manikin itself is made of wood and propped up with a small peg, the abdominal wall and genital area are made of rubber and appear to be attached to the base of the manikin with bands of adhesive material. The article accompanying the illustration describes the manikin as follows: “the thighs are widely separated for convenience in operating, and the anterior abdominal wall is made of rubber capable of being distended with air, and so arranged on a frame hinged to the upper part of the body, that the whole may be thrown back, thus bringing the abdominal cavity and pelvic inlet into view. The pelvic excavation is so carved as to roughly represent the normal bony pelvis. And one piece of India rubber lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. And at the pelvic outlet is so moulded and secured to the margin of the inferior strait as to form the vulva, vagina, and perineum” (702).

Budin-Pinard Obstetric Manikin This page from J. Clifton Edgar’s “The Manikin in the Teaching of Practical Obstetrics,” published in “The New York Medical Journal” (December 1890), includes illustrations of a Budin-Pinard obstetric manikin, which was used to teach medical students. The illustrations are rendered in black and white and show the manikin with close attention to detail. The manikin represents the torso of a female body, from just above the breasts to a few inches above the knee. Crucial to the manikin’s function are its rubber vulva, anus, and inflated anterior abdominal wall. Whereas the manikin itself is made of wood and propped up with a small peg, the abdominal wall and genital area are made of rubber and appear to be attached to the base of the manikin with bands of adhesive material. The article accompanying the illustration describes the manikin as follows: “the thighs are widely separated for convenience in operating, and the anterior abdominal wall is made of rubber capable of being distended with air, and so arranged on a frame hinged to the upper part of the body, that the whole may be thrown back, thus bringing the abdominal cavity and pelvic inlet into view. The pelvic excavation is so carved as to roughly represent the normal bony pelvis. And one piece of India rubber lines the abdominal and pelvic cavities. And at the pelvic outlet is so moulded and secured to the margin of the inferior strait as to form the vulva, vagina, and perineum” (702). -

Miscarriage Specimens A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints).

Miscarriage Specimens A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints). -

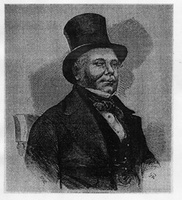

A Policeman's Hat This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material.

A Policeman's Hat This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material. -

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset.

William Macready & Charles Dickens's Scrap Screen This elaborate folding screen is composed of four wooden leaves, each covered entirely by an assortment of square and rectangular paper cut-outs. Each individual leaf spans 202cm by 77.5cm, and the total length of the screen when extended is 310cm. Although the photographs above show only the front side of the screen, both sides are covered entirely in black-and-white images. Boasting approximately four hundred engravings overall, the folding screen displays an array of yellowed scraps of paper dating from the 1820s to the 1840s. These decoupaged images have been meticulously pasted onto the front and back of the screen and subsequently varnished. There are no gaps showing between the images, nor do their edges overlap. Covering a range of artistic genres, these engravings include portraits, historical paintings, and scenes from well-known plays. While the folding screen was made some time around 1860, the photograph above shows the object in its current state, housed in the collections of Sherborne House, in Dorset. -

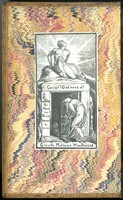

George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection" These images come from a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s "Aids to Reflection" that belonged to Victorian author George MacDonald. One image shows the volume’s title page. This page is yellowed by time and contains a handwritten inscription in black ink in the top right corner to Louisa Powell, along with the date, “Nov. 5. 1847.” Below this inscription and the printed title is a sonnet written in the same script as the name and date. The first few letters of each line of the sonnet are obscured by the crease of the page. Other images show the black-and-white bookplate, bearing the name of “Greville Matheson MacDonald” and set against colourful marbled paper. The illustration on the bookplate depicts two figures, a muscular young man sitting atop a cavernous entryway shrouded in darkness, and another man, stooped with age, carrying a cane, and walking across the threshold of the same entrance. The darkness of the entryway contrasts with light emitting from the young man. The lintel of the cave bears the text “Corage! God mend al!” while the left post bears an image of a hand holding up a cross and the Latin text “per mare per terras domum tu erras” (“through sea and through land, you wander homeward”). At the bottom left-hand corner of the doorway is a Latin epsilon followed by the text “x Libris.” The book is currently held at the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University as part of their George MacDonald collection. The inscription (as transcribed by Dr. Denae Dyck and Dr. Melinda Creech) reads as follows: [?Whether] this day on earth shall often be, [?I h]ave no wish that I can make for thee. [?Nor] will I wish thee ever cloudless years. [?Why] wish thee that which cannot be, I know [?That] as the sun must shine, so clouds must grow. [?And] as our being is, so are our tears: [?And] one who hath given thanks for sorrow’s hour [?May] never pray thou shouldst not know its power; [?Ye]t there is one thing I can wish for thee – [?That] the unbounded promise may be thine [?When] all things in one Providence combine [?So]rrows and joys in glorious unity – [?But] bright or dark, unknown or understood, [?All] things work together for thy good.

George MacDonald's Copy of "Aids to Reflection" These images come from a copy of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s "Aids to Reflection" that belonged to Victorian author George MacDonald. One image shows the volume’s title page. This page is yellowed by time and contains a handwritten inscription in black ink in the top right corner to Louisa Powell, along with the date, “Nov. 5. 1847.” Below this inscription and the printed title is a sonnet written in the same script as the name and date. The first few letters of each line of the sonnet are obscured by the crease of the page. Other images show the black-and-white bookplate, bearing the name of “Greville Matheson MacDonald” and set against colourful marbled paper. The illustration on the bookplate depicts two figures, a muscular young man sitting atop a cavernous entryway shrouded in darkness, and another man, stooped with age, carrying a cane, and walking across the threshold of the same entrance. The darkness of the entryway contrasts with light emitting from the young man. The lintel of the cave bears the text “Corage! God mend al!” while the left post bears an image of a hand holding up a cross and the Latin text “per mare per terras domum tu erras” (“through sea and through land, you wander homeward”). At the bottom left-hand corner of the doorway is a Latin epsilon followed by the text “x Libris.” The book is currently held at the Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University as part of their George MacDonald collection. The inscription (as transcribed by Dr. Denae Dyck and Dr. Melinda Creech) reads as follows: [?Whether] this day on earth shall often be, [?I h]ave no wish that I can make for thee. [?Nor] will I wish thee ever cloudless years. [?Why] wish thee that which cannot be, I know [?That] as the sun must shine, so clouds must grow. [?And] as our being is, so are our tears: [?And] one who hath given thanks for sorrow’s hour [?May] never pray thou shouldst not know its power; [?Ye]t there is one thing I can wish for thee – [?That] the unbounded promise may be thine [?When] all things in one Providence combine [?So]rrows and joys in glorious unity – [?But] bright or dark, unknown or understood, [?All] things work together for thy good. -

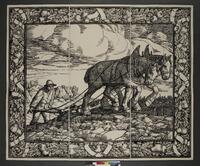

William Strang's "The Plough" “The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture.

William Strang's "The Plough" “The Plough” is an extremely large woodcut print, measuring five feet tall by six feet wide and printed from nine separate wood blocks. Created by artist William Strang for schoolrooms, the image is made up of individual black lines forming patterns of light and dark. The central image focuses on two large horses harnessed to a wooden plough that loosens and turns the soil while a farmer follows behind them, holding the plough. The ground is a slightly sloped hill, uneven and rocky with patches of grass, and both the horses and man appear tired. The background is made up of a clouded sky; a rolling landscape of hills, trees, and a cliff; and bundles of straw. The central image is surrounded by an intricate border, featuring a repeating pattern of ribbons, leaves, and fall produce, including squash and pumpkins. Two vertical white lines are visible, marking the boundaries where three sheets of two-foot-wide paper have been joined together to form the final picture. -

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf" Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration.

Clemence Housman's "The Were-Wolf" Clemence Housman’s "The Were-Wolf" is an illustrated novella published in 1896. Housman wrote the story and engraved the six illustrations, which were designed by her brother Laurence. The title page, printed in orange ink, acknowledges Clemence Housman as the author and Laurence Housman as the illustrator, as well as the novella’s publication date and its publishers in London and Chicago (John Lane and Way and Williams, respectively). However, as often happens in Victorian illustrated books, Clemence Housman’s role as the wood engraver remains unacknowledged. The engraved full-page illustration included here, “Rol’s Worship,” shows three young men working at a table; a small child hangs on to the legs of the man on the left. The background includes two women, partly obscured by the figures in the foreground. The various textures of wooden flooring, human skin, and fabric are represented by patterns of wood-engraved cross-hatched lines. Denser hatching suggests shadow on the ceiling and floor; white space and lighter patterns of lines show where backlighting brightens the scene. In the bottom left corner, Laurence Housman’s initials appear in block capitals. The complete, rectangular image is framed by white space but not centred on the page, leaving a greater amount of blank paper below and to the right of the illustration. -

Mrs. Alexander's Mark This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page. The body text of the page reads: labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys: “Though my lot be hard and lonely, Yet I hope – I hope through all.” The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library.

Mrs. Alexander's Mark This page is from "Women Novelists of Queen Victoria’s Reign: A Book of Appreciations," published in London by Hurst and Blackett in 1897. It features standard black letter text on white paper. In addition to the body text, the page features three women’s names. First, “Mrs. Norton,” the subject of this chapter, runs across the top of the page. Second, the signature of “Annie Hector” appears directly under the body text at the centre of the page, underscored by a jagged flourish. Lastly, the name “Mrs. Alexander” appears inside both quotation marks and parentheses. Though the last name is in capital letters, its font is noticeably smaller than the two other names and somewhat smaller than the body text. The page number appears in parentheses at the bottom of the page. The body text of the page reads: labour. In her day, the workers were few, and the employers less difficult to please. But these comparisons are not only odious, but fruitless. The crowd, the competitions, the desperate struggle for life, exists, increases, and we cannot alter it. We can but train for the contest as best we may, and say with the lovely and sorely tried subject of this sketch, as she writes in her poem to her absent boys: “Though my lot be hard and lonely, Yet I hope – I hope through all.” The copy of the book featured here is housed at the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library. -

J. M. Whistler's "The Fleet: Monitors" “The Fleet: Monitors” from James McNeill Whistler’s “Jubilee Set” portrays the naval review of Queen Victoria’s 1887 Jubilee and five onlookers. The etching, completed in black ink on laid ivory paper, uses broken lines to outline an array of steam-powered ships with tall masts in the background. Additional ships are depicted with less detail on the left-hand side. Minimal linework suggests the forms of a few clouds in the sky as well as waves in the river. Four men and one woman stand in the left foreground and they all lack facial detail. The woman wears a sunhat and is looking towards the naval display. The first man from the left wears a hat and has a moustache; the second wears a hat and is reading a book; the third and fourth are also wearing hats and are drawn with the least amount of detail. All four men face the foreground, looking away from the ships that make up the background of the etching. The etching as a whole is dominated by negative space, punctuated by thin, spare lines. The paper is textured, and the print featured here, from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, has slight discolouration around the edges. Some unevenness in the print tone is evident on the left side of the etching. Relatively small, the print is 14.3 by 22.1 centimetres, or 5.6 by 8.7 inches.

J. M. Whistler's "The Fleet: Monitors" “The Fleet: Monitors” from James McNeill Whistler’s “Jubilee Set” portrays the naval review of Queen Victoria’s 1887 Jubilee and five onlookers. The etching, completed in black ink on laid ivory paper, uses broken lines to outline an array of steam-powered ships with tall masts in the background. Additional ships are depicted with less detail on the left-hand side. Minimal linework suggests the forms of a few clouds in the sky as well as waves in the river. Four men and one woman stand in the left foreground and they all lack facial detail. The woman wears a sunhat and is looking towards the naval display. The first man from the left wears a hat and has a moustache; the second wears a hat and is reading a book; the third and fourth are also wearing hats and are drawn with the least amount of detail. All four men face the foreground, looking away from the ships that make up the background of the etching. The etching as a whole is dominated by negative space, punctuated by thin, spare lines. The paper is textured, and the print featured here, from the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, has slight discolouration around the edges. Some unevenness in the print tone is evident on the left side of the etching. Relatively small, the print is 14.3 by 22.1 centimetres, or 5.6 by 8.7 inches. -

The "Ladies Carpet" The “Ladies Carpet,” designed by English architect J.W. Papworth and displayed at the Great Exhibition in 1851, is an example of Berlin wool work. The carpet measured thirty by twenty feet and consisted of one hundred and fifty squares, each measuring two feet by two feet. The squares were made and pieced together by “one hundred and fifty ladies of Great Britain,” as proclaimed under the published design of the carpet. Red and green accents dominate the intricate design, with red roses and green vines surrounding an inner rectangle. Small union jacks appear on all four corners of the carpet; two of the union jacks feature crests at their centres, while the other two feature the cross of Saint George. In the middle of the carpet, a V and an A interlock each other, paying homage to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The carpet’s current location is unknown.

The "Ladies Carpet" The “Ladies Carpet,” designed by English architect J.W. Papworth and displayed at the Great Exhibition in 1851, is an example of Berlin wool work. The carpet measured thirty by twenty feet and consisted of one hundred and fifty squares, each measuring two feet by two feet. The squares were made and pieced together by “one hundred and fifty ladies of Great Britain,” as proclaimed under the published design of the carpet. Red and green accents dominate the intricate design, with red roses and green vines surrounding an inner rectangle. Small union jacks appear on all four corners of the carpet; two of the union jacks feature crests at their centres, while the other two feature the cross of Saint George. In the middle of the carpet, a V and an A interlock each other, paying homage to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. The carpet’s current location is unknown. -

Kate Greenaway's Design for Nursery Wallpaper This sample of nursery wallpaper features illustrations by the artist Kate Greenaway of children engaged in various seasonal activities. Some of the children pick apples and berries, while others walk in rain or snow. The children are dressed in the style of the Regency period, and, even while at play, their expressions remain stoic. The illustrations are set against a cream-coloured backdrop adorned with pink flowers and bows. Though perhaps faded by time, the pastel colours likely always appeared subdued. The name of the month in which the scene takes place appears under each illustration along with the artist’s initials, “KG,” in smaller print. The text around the border of the wallpaper repeats three phrases: “Reproduced by Special Permission from Drawings by Kate Greenaway,” “English Made 2258,” and, surrounding an image of a crown, “Trade Mark.” The wallpaper sample is currently housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Kate Greenaway's Design for Nursery Wallpaper This sample of nursery wallpaper features illustrations by the artist Kate Greenaway of children engaged in various seasonal activities. Some of the children pick apples and berries, while others walk in rain or snow. The children are dressed in the style of the Regency period, and, even while at play, their expressions remain stoic. The illustrations are set against a cream-coloured backdrop adorned with pink flowers and bows. Though perhaps faded by time, the pastel colours likely always appeared subdued. The name of the month in which the scene takes place appears under each illustration along with the artist’s initials, “KG,” in smaller print. The text around the border of the wallpaper repeats three phrases: “Reproduced by Special Permission from Drawings by Kate Greenaway,” “English Made 2258,” and, surrounding an image of a crown, “Trade Mark.” The wallpaper sample is currently housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum.