Layette Pincushion

Item

-

Title

-

Layette Pincushion

-

Description

-

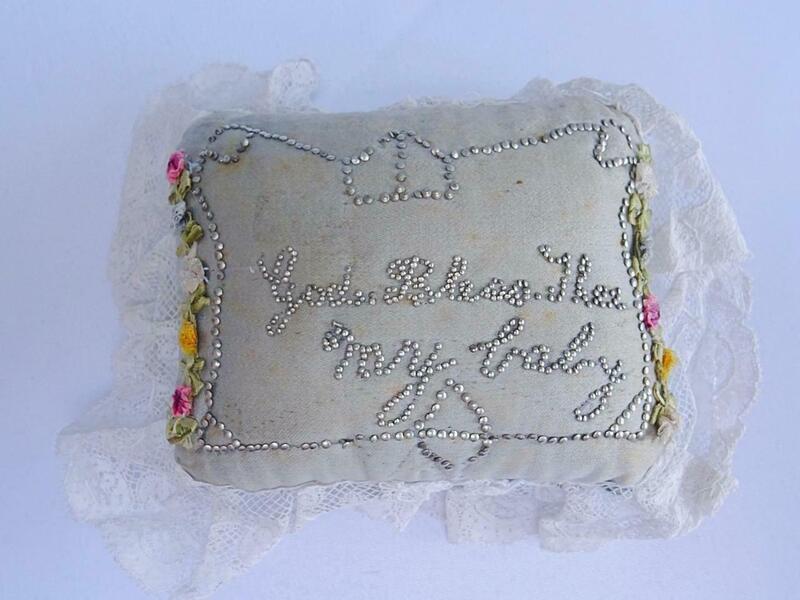

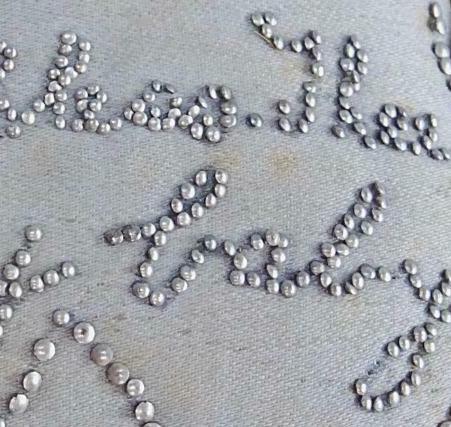

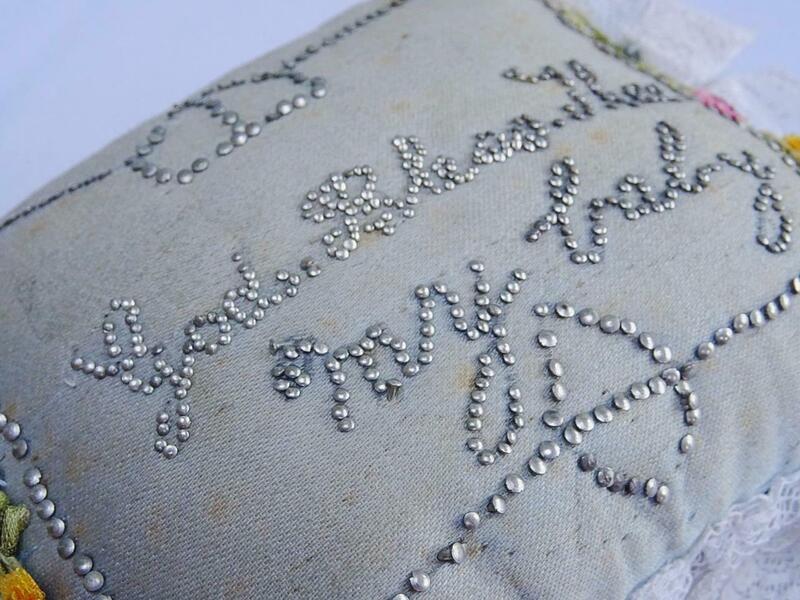

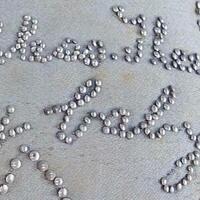

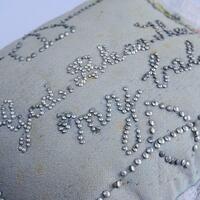

This layette pincushion is made of light-blue fabric, faded from the sun and mottled in places. A message pricked out in pins reading “God Bless Thee my baby” appears in cursive in the centre of the cushion. The first three words are capitalized and separated by pinheads. A curved frame of pinheads surrounds the message, and there are decorative details at the top, bottom, centre, and corners of the frame. The top decoration resembles a crown, and the bottom decoration either a teardrop or a leaf. The corners of the frame are marked with triangular shapes. To the left and right of the pinhead frame, there are curved floral designs of ribbon rosettes in pink, blue, yellow, and white, and leaves in soft green. White lace trims all four sides of the cushion, which measures five inches wide, three and three-quarters inches deep, and two inches high. The pincushion’s provenance is unknown, but it most likely formed part of a baby’s layette and seems to have been made by its mother, as suggested by the possessive “my” in the message.

-

MARY ELIZABETH LEIGHTON AND LISA SURRIDGE ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

A layette pincushion is a decorative object that holds the pins for diapers and clothing for a newborn. Until the 1800s, pins were expensive, but as they became cheaper, they came into common use. Safety pins were patented as early as 1849 but remained uncommon until they were successfully marketed in the 1870s. Until then, straight pins were essential for fastening newborn diapers and the back of garments. Dr. Leighton and Dr. Surridge note that a diaper usually required 8 to 10 pins.

Pincushions were part of the wider mid-Victorian fashion for souvenirs and trousseau gifts. Layette pincushions had both practical and sentimental functions: practical because they could be used to supply and hold diaper and clothing pins, and sentimental because they were often made by or gifted to an expectant mother as her delivery approached. Messages were sometimes addressed to a future, imagined child, as in “Welcome Little Stranger,” or even invoked a blessing on that child, as in “God Bless This Babe.” In either case, the layette pincushion would have been pricked out before a child’s birth. Dr. Leighton and Dr. Surridge remind us that the infant mortality rate during this period was one-hundred-forty-nine per thousand live births, and so such messages represent hopeful sentiments on the part of expectant mothers.

The messages of the layette pincushions to the unborn are both potentially ephemeral (because, in some cases, pins would have been removed) and strangely permanent. Pincushions were often made of silk, a fabric that preserves traces of use. On this particular pincushion, we can see where pins have been removed from the start of the “G” in “God,” the downward loop of the “y” in “my,” and at the bottom of the leaf-shaped decoration. Notably, the pins in this cushion are short, suggesting their use was limited to decoration.

We cannot know for sure if these pins were removed to be used or if they fell out, but there is one more possibility, as Dr. Leighton and Dr. Surridge explain. During the nineteenth century, such pins became associated with labour pain, as expressed in the saying “For every pin, a pain.” If you gave a pincushion to a woman before childbirth, she might have pulled out the pins in a symbolic effort to reduce her anticipated suffering. As this custom suggests, layette pincushions were associated with expectation and bridged the experiences of pregnancy and childbirth, being created before labour but addressed to the “little stranger” whose arrival might follow that labour.

Consider the message “God Bless Thee my baby.” For this message to be fully realized, both mother and child must survive; otherwise, the message becomes either a legacy from the dead mother to the surviving infant or a memento mori for a stillborn baby and possibly for its dead mother, too. As Dr. Leighton and Dr. Surridge suggest, we have no way of knowing how the messages on surviving layette pincushions reverberated in their owners’ lives, but these objects are themselves pregnant with poignant possibilities.

-

Rights Holder

-

Private collection; photographs courtesy of Kelly Griffin