Miscarriage Specimens

Item

-

Title

-

Miscarriage Specimens

-

Description

-

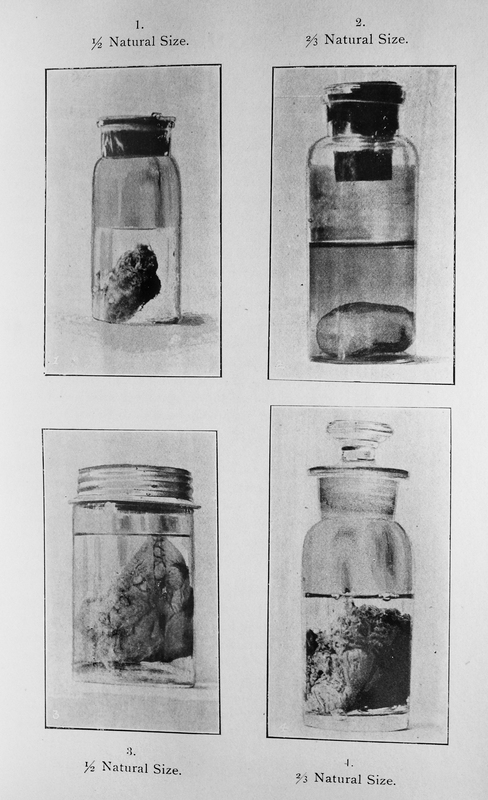

A single printed page from the “Transactions of the Michigan State Medical Society for the Year 1896” displays four images of fetal tissue in glass jars, each labelled in a small serifed font. These photographs appear in a medical article by William C. Stevens titled “Partial Abortion; Expulsion of the Amniotic Sack Alone; Three Specimens,” which demonstrates how late-century medical professionals used such specimens. Captions for each image describe the size of the specimens: specimen 1, at the top left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 2, at the top right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size”; specimen 3, at the bottom left-hand corner, is “½ natural size”; specimen 4, at the bottom right-hand corner, is “2/3 natural size.” The details of the specimens are unclear due to the grainy quality of the halftones (a type of mechanical reproduction that allowed photographs to be reproduced as prints).

-

SHANNON WITHYCOMBE ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

Dr. Withycombe draws our attention to the prevalence of using specimen jars to hold, study, view, and display medical tissues obtained by doctors from women and their families who agreed to donate tissue from miscarriage for such a purpose. She explains how this practice of collecting specimens drove professionalizing physicians into the “miscarriage business,” contributing to the complex social meanings of pregnancy loss.

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, doctors began obtaining physical, visual clues to the process of human development when young, poor women (many of whom were women of colour or immigrants) moved to urban centres, away from family support and traditional birthing practices. These women had to rely on white, male physicians for assistance with miscarriage and childbirth. Dr. Withycombe explains that as doctors encountered more miscarriage cases, they began to revise their previous assumption that human development was hidden and mysterious. Instead, doctors increasingly viewed embryological and placental tissues obtained from miscarriages as important scientific specimens for the study of human development.

By the 1870s, specimens were present in doctors’ offices and medical classrooms across the United States, often displayed in clear jars for easy viewing. Dr. Withycombe characterizes these changes as effecting a transformation of miscarriage from a family event to a scientific one, and notes that doctors used so-called scientific specimens to position themselves as more knowledgeable than American midwives, who usually disposed of such tissue.

However, as Dr. Withycombe reminds us, race- and class-based power dynamics meant that doctors could remove tissue without much consideration of what women might want or think. Nevertheless, some women who provided specimens did have agency: Dr. Withycombe cites one example of a doctor who bemoaned his failure to convince a family to provide the miscarriage tissue of twins for scientific purposes, suggesting that women, their families, and their female caregivers were able to object to the medical use of miscarriage products.

Dr. Withycombe also considers the importance of women seeking to limit their family’s size, particularly working women in urban centres and women among the growing middle class, the latter of whom saw smaller numbers of children as a sign of status. Because the American government criminalized abortion and birth control, leaving many families with costly, dangerous, or non-existent fertility-control measures, miscarriages were not always experienced as tragic or unwelcome. Some women found the scientific use of fetal tissue less objectionable than other disposal methods: Dr. Withycombe references late-nineteenth-century newspaper articles expressing dismay at miscarriage tissue being disposed of in furnaces or rivers.

While some newspaper articles described such disposal practices as barbaric and horrific, the display of preserved specimens at a museum in 1887 was deemed acceptable by the press. This exhibit attracted thousands of viewers for entertainment and education, including families with young children. Contrasting the reception of these two disposal practices, Dr. Withycombe argues that the scientific framing of miscarriage specimens in jars was viewed by many Americans as educational. The gathering of miscarriage specimens established much of the embryological knowledge that doctors still use today—and, as Dr. Withycombe emphasizes, the practice could benefit women as well.

-

Rights Holder

-

Images courtesy of Google Books; photographed from material in University of Michigan Library