Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage

Item

-

Title

-

Minutes of Evidence on Gardner Peerage

-

Description

-

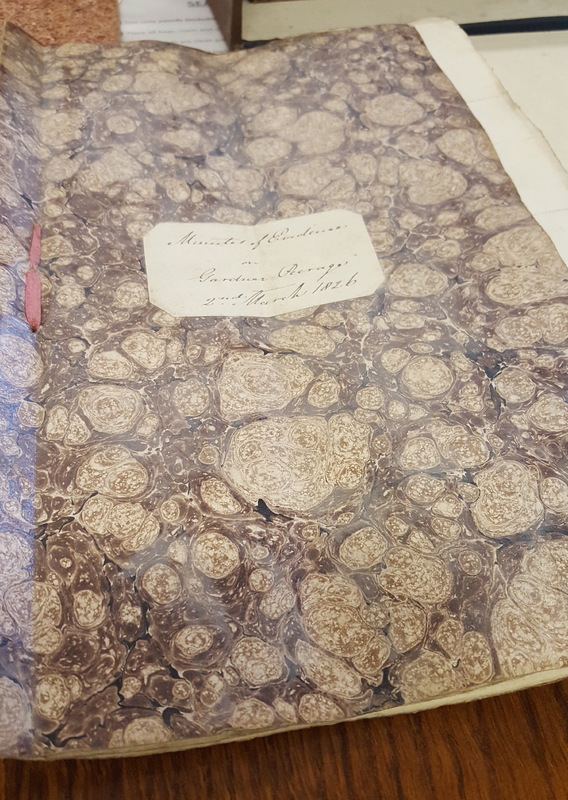

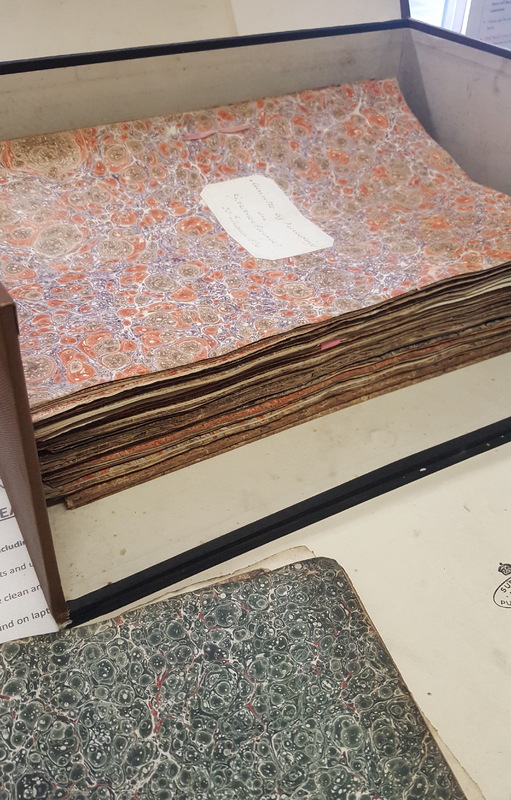

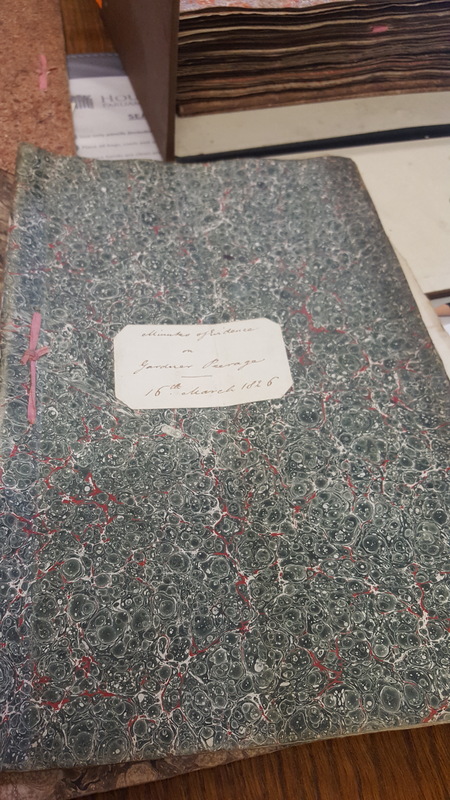

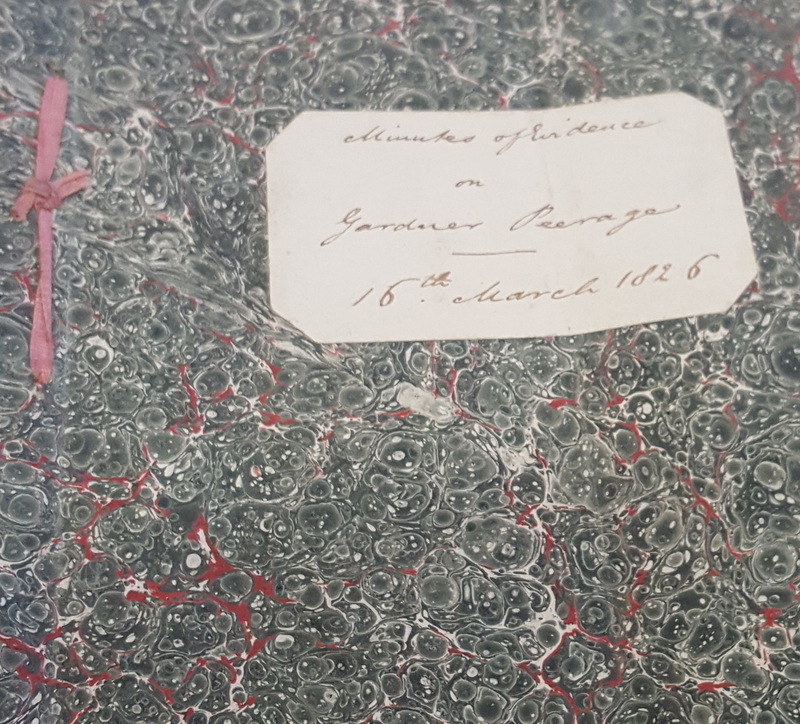

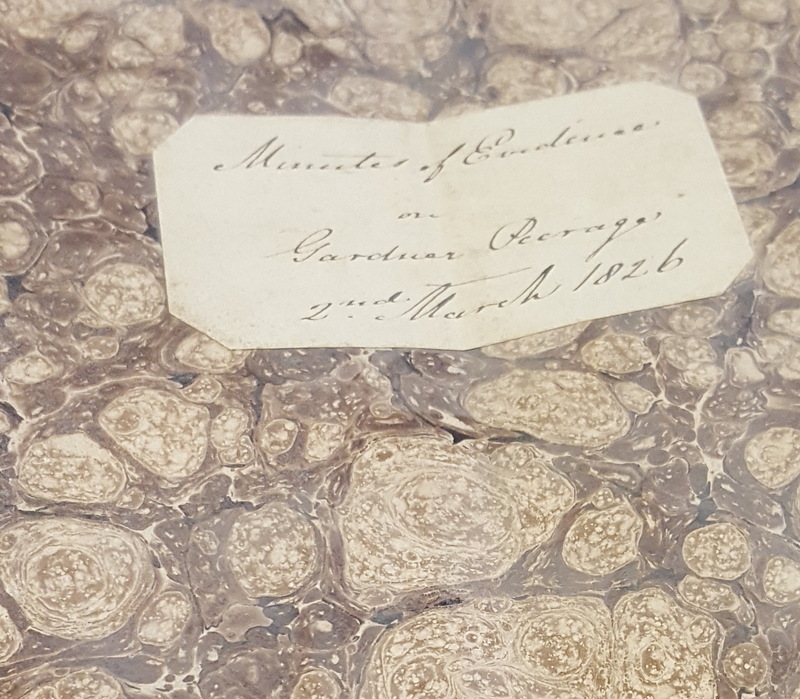

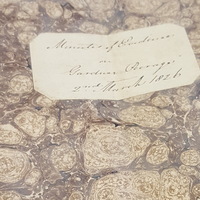

Currently housed at the UK Parliamentary Archives, these handwritten manuscripts record the proceedings of the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords in London. With covers of hand-marbled paper, each booklet displays the date and the title of the case in the secretary’s handwriting on its cover. Each book contains a new day of proceedings, with each witness beginning on a new page. The paper is thick and textured, with the marbled covers taking on different dominant hues: green, red, or beige. The booklets are bound loosely with a red ribbon.

-

ISABEL DAVIS ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

The Gardner Peerage case concerned a disputed pregnancy: a child was born to Mrs. Gardner in December 1802, while her husband, Captain Gardner, was in command of “The Resolution,” which had been sailing in the Caribbean between February and July of that year. Some twenty years later, this legal case took up the issue of whether that child could inherit the Gardner baronetcy.

Dr. Davis notes the variety of evidence heard in the case, explaining that medical evidence on the length of gestation accompanied domestic evidence from household servants about Mrs. Gardner’s extra-marital affair, concealed pregnancy, and delivery. The affair was well documented and undisputed; nevertheless, Dr. Davis tells us, the child’s lawyers argued that if it was possible for a pregnancy to gestate longer than ten months, then Captain Gardner could have been the child’s father, making the inheritance possible. Because paternity testing did not exist at the time, the legal system declared that if a woman’s husband could feasibly have fathered the child, then he would be deemed the legal father.

Dr. Davis characterizes these legal papers as instruments of empire. Reading the papers suggests how the geographical reach of the British empire shaped the lives of imperial servants. For example, the Gardners met in Fort St. George, today located in India, before moving to a London townhouse, where Mrs. Gardner eventually conducted her affair and secretly gave birth. Meanwhile, her husband protected British interests—namely, sugar plantations—in the Caribbean. Captain Gardner was also personally invested in this project: his mother’s family owned such plantations. Dr. Davis argues that the court was interested primarily in determining paternity for the purposes of determining who should inherit the father’s property, including the dividends of slavery—a system that was maintained through interventions in enslaved people’s reproductive lives. The booklets detailing the Gardner Peerage case thus highlight the material ways that patriarchal power and imperial power were exerted through reproduction.

Dr. Davis emphasizes how much information is contained in the manuscripts, including the material history of pregnancy and childbirth—such as where to buy linen in London and how it was washed and prepared—and the roles of servants and midwives in pregnancies. She underscores the value of these booklets and the material they provide for those interested in studying birth and pregnancy in the context of empire.

-

Rights Holder

-

Parliamentary Archives, London (HL/PO/JO/10/8/711 and HL/PO/JO/10/8/744)