Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait

Item

-

Title

-

Dinah Craik’s Hidden Mother Portrait

-

Description

-

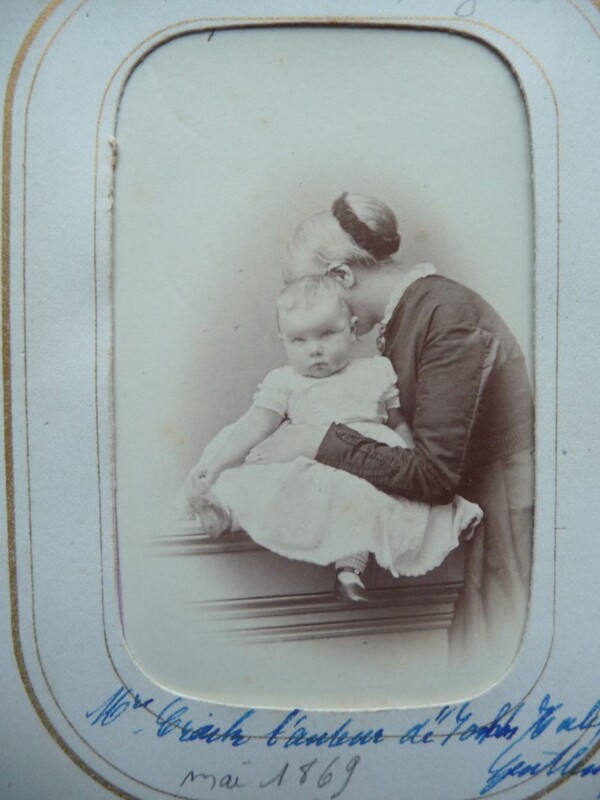

In this black-and-white photograph, Dinah Craik embraces her sixteen-month-old adopted daughter, Dorothy. Craik stands beside her daughter, her left hand winding around her waist, while she bends to obscure her own face entirely behind Dorothy’s head. The photograph, which is housed in a private collection, is a portrait of Dorothy, whose gaze is directed at the viewer. Wearing mary jane-style shoes and a white-frilled dress that complements a similar white frill on her mother’s collar, Dorothy sits patiently with her arms relaxed at her sides. All that is visible of Craik herself are her hand, body, and ear, as well as her muted, conventional clothing and a dark band around her hair. Written across the bottom of the white and gold cardboard frame in blue ink are the words “Mrs. Craik l’auteur de John Halifax, Gentleman / mai 1869.”

-

KAREN BOURRIER ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

This photograph shows the popular Victorian novelist Dinah Craik embracing her daughter, Dorothy. Craik had adopted Dorothy four months earlier on New Year’s Day, when the infant was found abandoned behind a stack of bricks in the London suburb of Bromley. The photograph, which purposefully obscures Craik’s face, is part of a genre that artist Linda Fregni Nagler identifies as “Victorian hidden mother portraits”: portraits in which the mothers are obscured by upholstery or cropping, creating an uncanny ghostly presence.

Today, we might be inclined to view this photograph as a sign of Craik’s maternal self-effacement, but Dr. Bourrier points out that there is a practical reason for her obscurity. Long exposure times in Victorian photography presented a difficulty for those wishing to take portraits of infants and small children. In these circumstances, the mother’s calming presence could help keep the child still and calm. In the introduction to Nagler’s book on “The Hidden Mother,” art historian Geoffrey Batchen’s notes that, in viewing these portraits, we are asked to witness an act of “modesty and self-effacement” on the part of these figures but also to examine a picture of “a woman’s place in a patriarchal society,” where she is inevitably figured as “without an identity of her own” (6).

Over the course of Craik’s long and successful forty-year career as a woman writer, writing for young people played an important role both before and after her adoption of Dorothy. Although Craik circulated what we would now call a “hidden mother portrait” privately, Dr. Bourrier informs us that this particular portrait was given to former French Prime Minister François Guizot, whose daughter, Henriette de Witt, was a children’s author with whom Craik collaborated. In this context, Dr. Bourrier suggests that we can understand the circulation of this private portrait as fostering a collaboration among children’s writers.

Dr. Bourrier reminds us that paratexts (in particular, dedications, prefaces, and frontispieces) play important roles in women’s claims to authority, as authors tend to dedicate children’s books to real children and to root the tales in an origin story in the preface. Whereas early criticism of children’s literature often dismissed origin stories that foreground the author’s relationship to real children as naïve and unsophisticated, recent work by Marah Gubar and Victoria Ford Smith shows the value of foregrounding children’s lived experience.

Craik, Dr. Bourrier tells us, deliberately grounded her early efforts to write for young people in her lived experience with children. Writing to her publisher about her early work, “Rhoda’s Lesson,” Craik requested the following: “But will you please put in this? ‘Dedicated to my little friends, Francis, Betty, and Jeanie.’ I do this not only to please myself, but because children readers take an interest in other real children, besides the fictitious ones of the story.” Similarly, Dr. Bourrier notes that in “Little Sunshine’s Holiday,” an account of a trip that the author took with three-year-old Dorothy to Scotland, Craik includes a portrait of Dorothy as a frontispiece but none of herself—again foregrounding the real child in the novel’s paratext.

It might be easy to interpret paratexts that foreground the author’s biographical relationship to real children as presenting women authors as amateurs—as mothers first and writers second. However, Dr. Bourrier suggests an alternate reading of this biographical material, one in which Victorian women writers foreground their relationships with real children in paratexts and images as a deliberate strategy of self-presentation and a claim to authority. She argues that in the case of the woman writer, it is possible to read the hidden mother in such portraits not as a figure of uncanny self-effacement, but rather as a strategy of self-presentation that foregrounds the writer’s knowledge of real children—and thus her authority to write about them.

-

Rights Holder

-

Private collection