A Policeman's Hat

Item

-

Title

-

A Policeman's Hat

-

Description

-

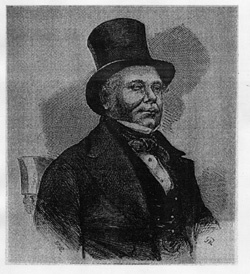

This black-and-white engraving of Charles Frederick Field, a retired detective of the Metropolitan Police Force, attributed to an 1855 issue of the “Illustrated News of the World,” features Field wearing his policeman's hat. In the image, Field sits on a chair with his torso facing slightly towards the right; the portrait captures the upper part of his torso and we can see the top part of the chair sketched in behind him. He wears a black top hat tipped back on his head as well as a version of the same clothing he would have adopted as a plainclothes detective: jacket, vest, white shirt, and cravat. A shadow behind him frames his head and adds depth to the image. The shading indicates that the hat is dark in colour but does not provide any information about the hat’s material.

-

KRISTEN GUEST ON WHAT THIS OBJECT TEACHES US:

Top hats are an example of how specific gendered, classed, and vocational forms of identity could be expressed through personal objects during the nineteenth century. By the 1840s, top hats had become symbols of respectability, wealth, and social standing. Silk toppers were worn by middle- and upper-class men during much of the Victorian era. Unlike such refined silk versions, stove-piped top hats worn by policemen as part of their uniforms were much hardier, reinforced with leather or cane, and intended to hold up to exposure and wear. Still, as Dr. Guest suggests, the shape of the policeman’s top hat visually associates the dress of a working man with that of his professional or leisured “betters.” The top hat thus suggests the increasing ambiguity of visual markers of identity in nineteenth-century men’s attire: the top hat no longer provided a guarantee of its wearer’s class identity.

Police uniforms more broadly showcase such ambiguities relating to class identity. Policemen wore top hats and swallow-tailed coats but also armbands bearing a constable’s number and division. Dr. Guest argues that this resulted in work that was presented to the public as a form of service, on the one hand, and as an aspiration to a higher place in society, on the other. Such discordant expressions of class coexisted without much difficulty until the formation of a plainclothes detective branch of the Metropolitan Police force in the early 1840s. As Dr. Guest puts it, moving undetected with the freedom to determine the place, time, and strategy of his actions, the self-directed plainclothes detective became a figure of fascination and anxiety since he enjoyed the prerogatives of a professional man while discarding the visual badge of service. Plainclothes detectives thus highlighted the problems associated with visually encoding identity in an increasingly mobile world.

Charles Frederick Field was a plainclothes detective and one of the first detectives associated with Scotland Yard; he was also the model for Inspector Bucket in Charles Dickens’s “Bleak House.” Dr. Guest claims that, in the engraving, Field’s top hat speaks to the ambiguity and malleability of objects as signifiers of identity. As a figure associated with both class anxieties and professional distinction as a plainclothes detective, Field’s appearance points towards tensions around masculinity and class differences at mid-century. Visually, the top hat connects him to both the aspirational professional classes and the uniformed, working class ranks of the police. The engraving does not show us whether his hat is made of silk, cane, or leather, and as a result, Field’s class position becomes difficult to discern.

However, Dr. Guest points out that the way Field wears his top hat does visually code him due to the way that it is tipped back on his head, which reveals that he is not top-hat born. This visual coding outs the detective as an interloper and renders his class position legible to select viewers. Standing between two worlds but wearing one hat, Field reminds us of how possessions—and the ability to wear them in particular ways—constituted a complex semiotic lexicon in the Victorian era.